Introduction

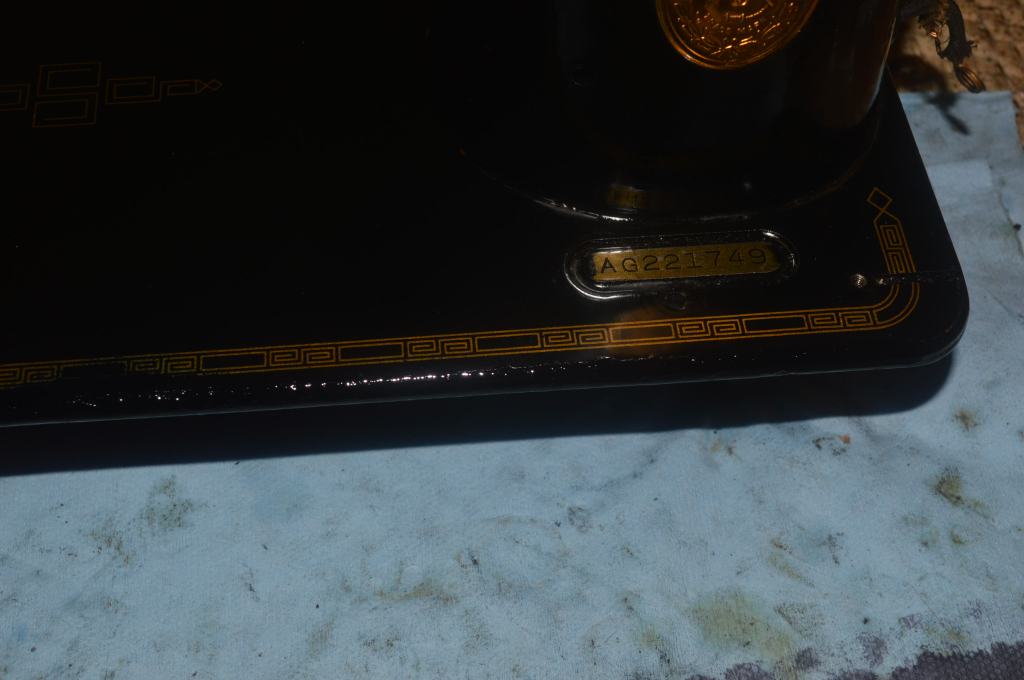

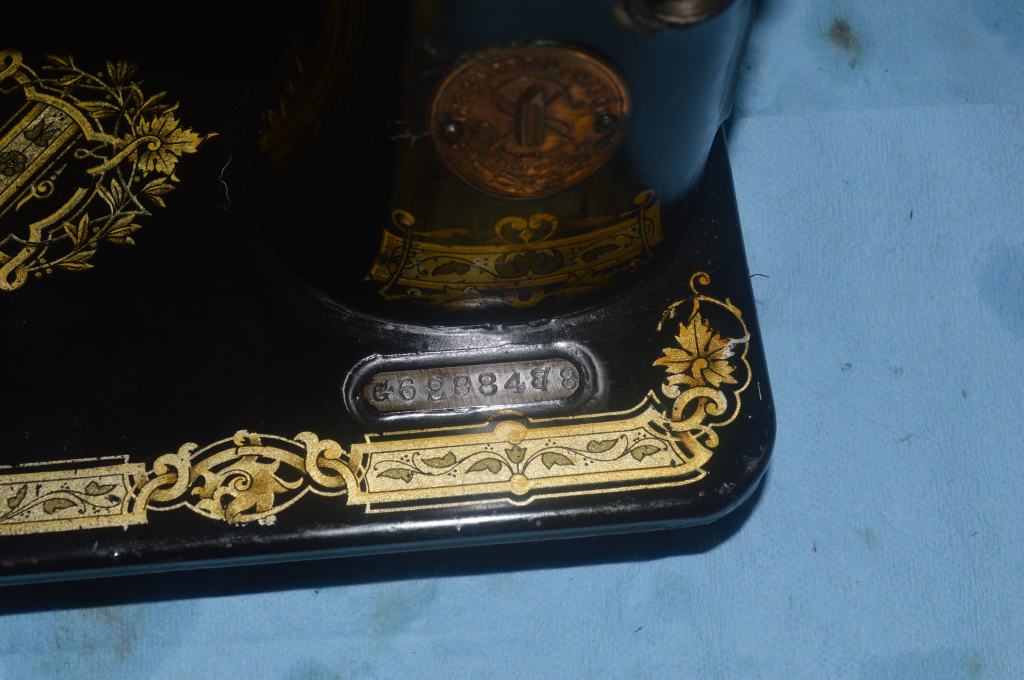

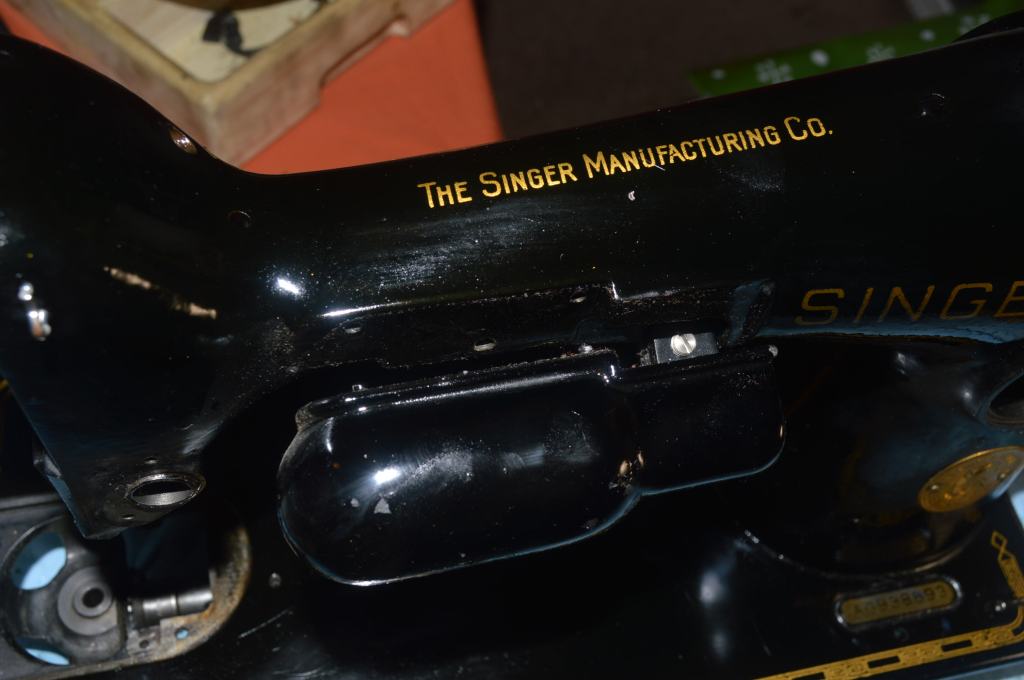

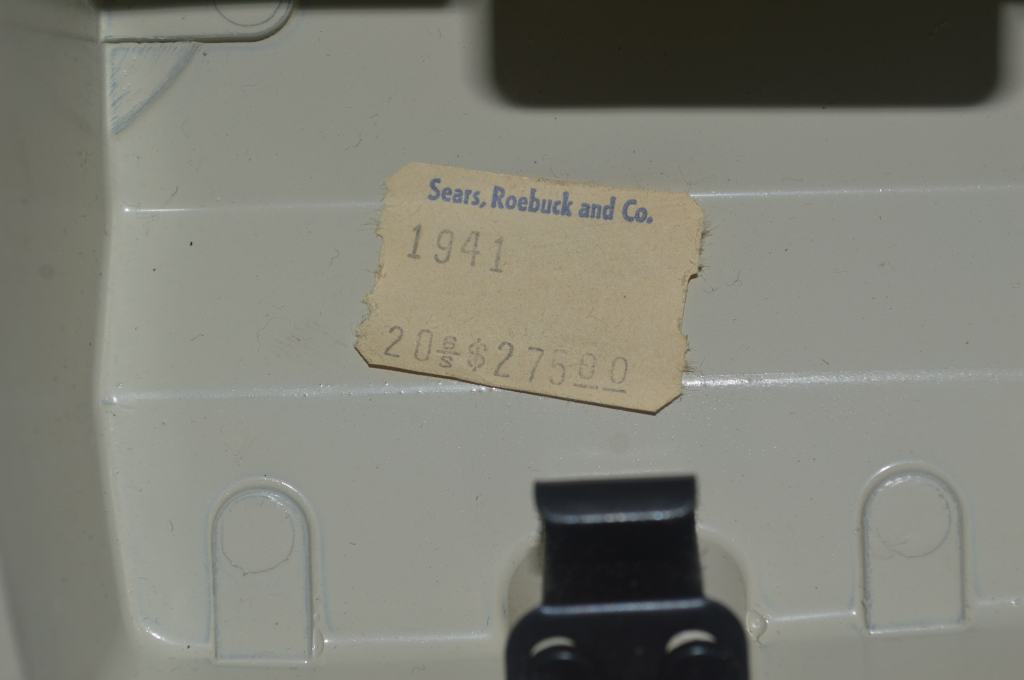

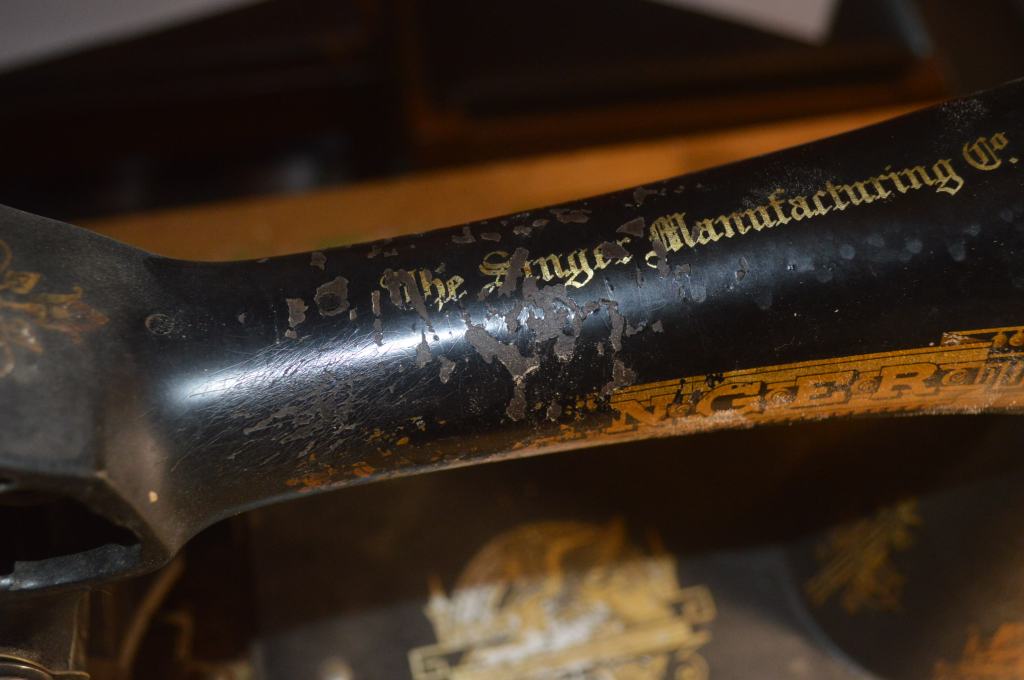

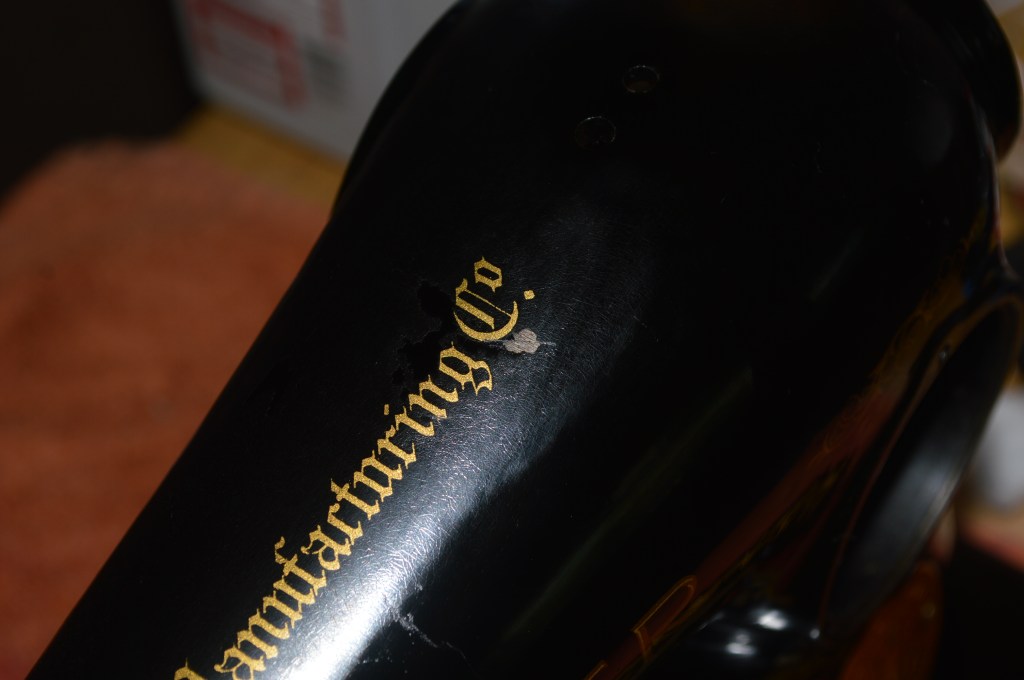

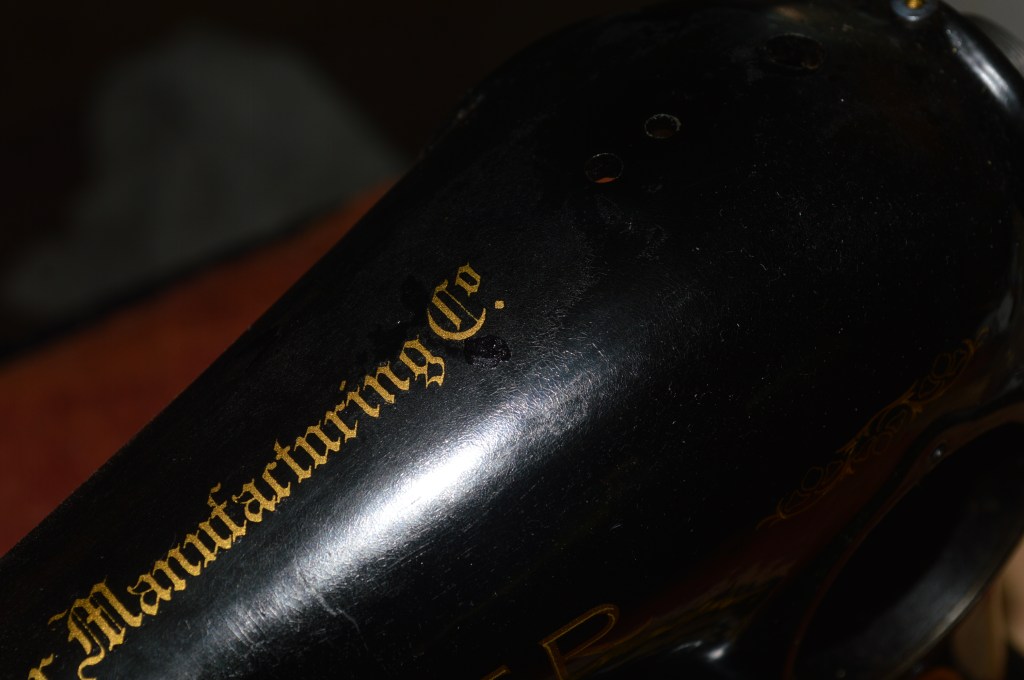

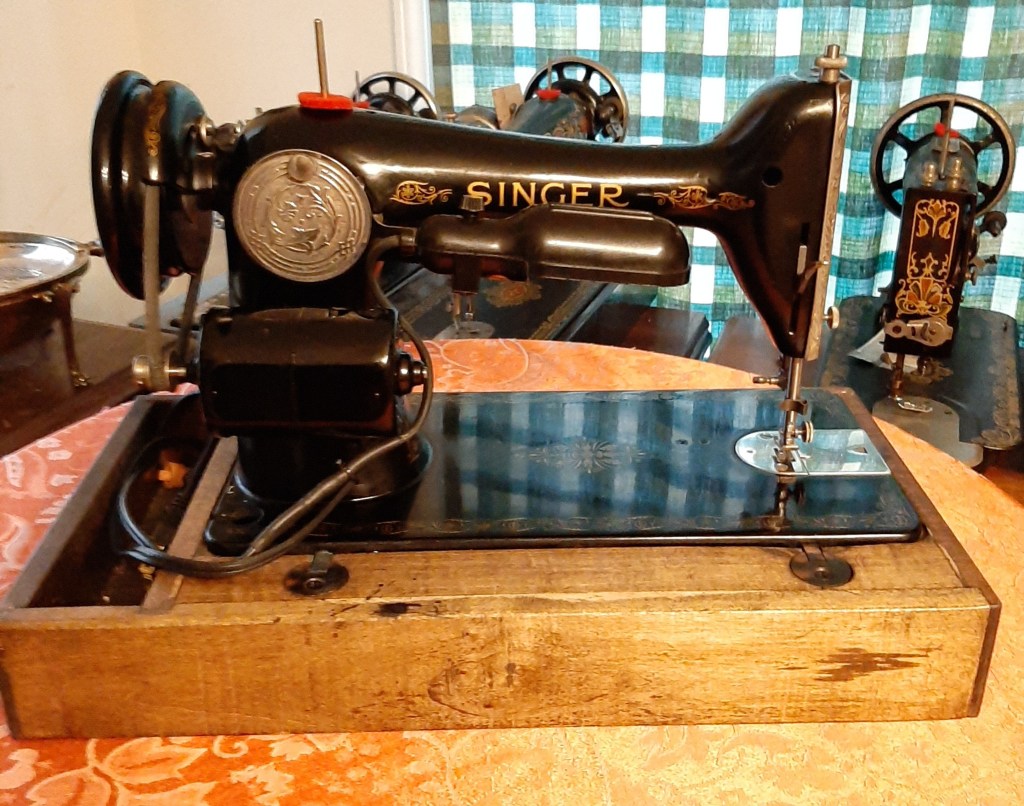

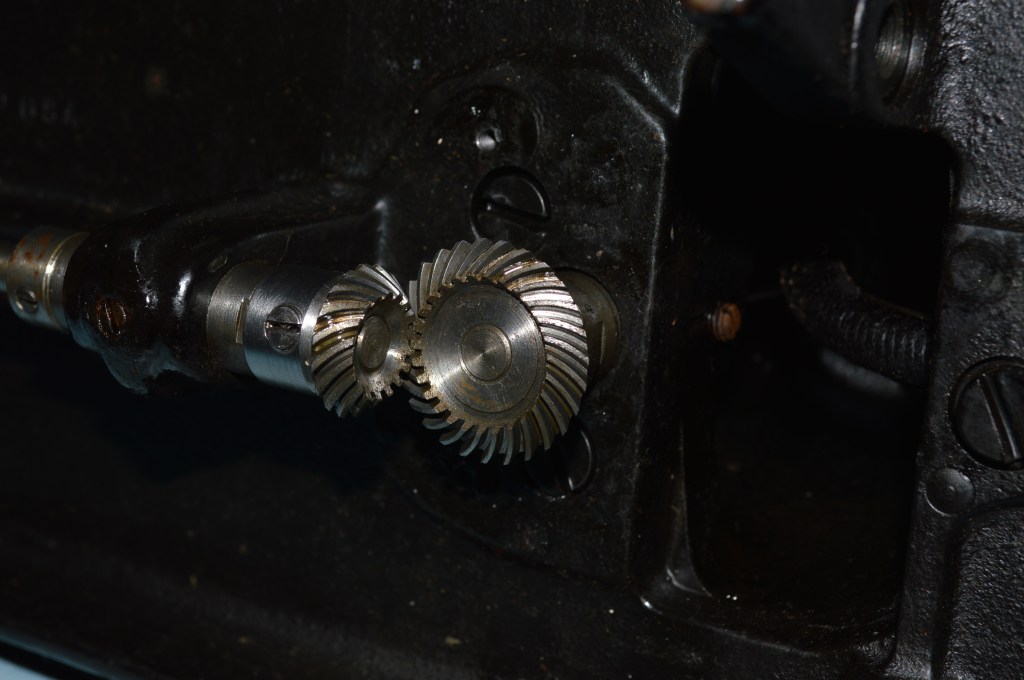

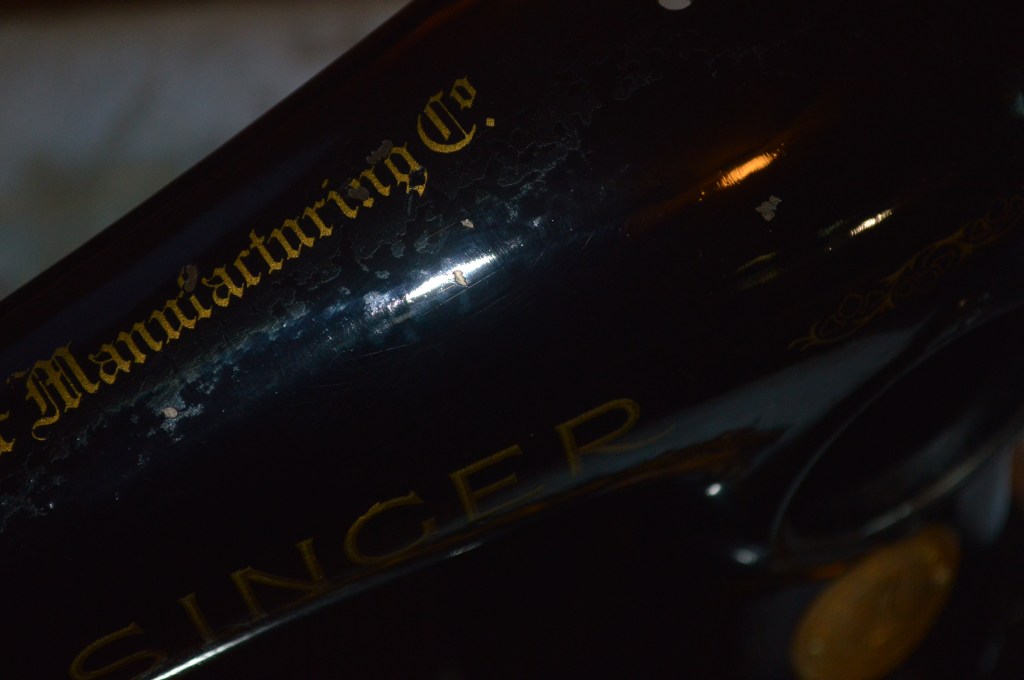

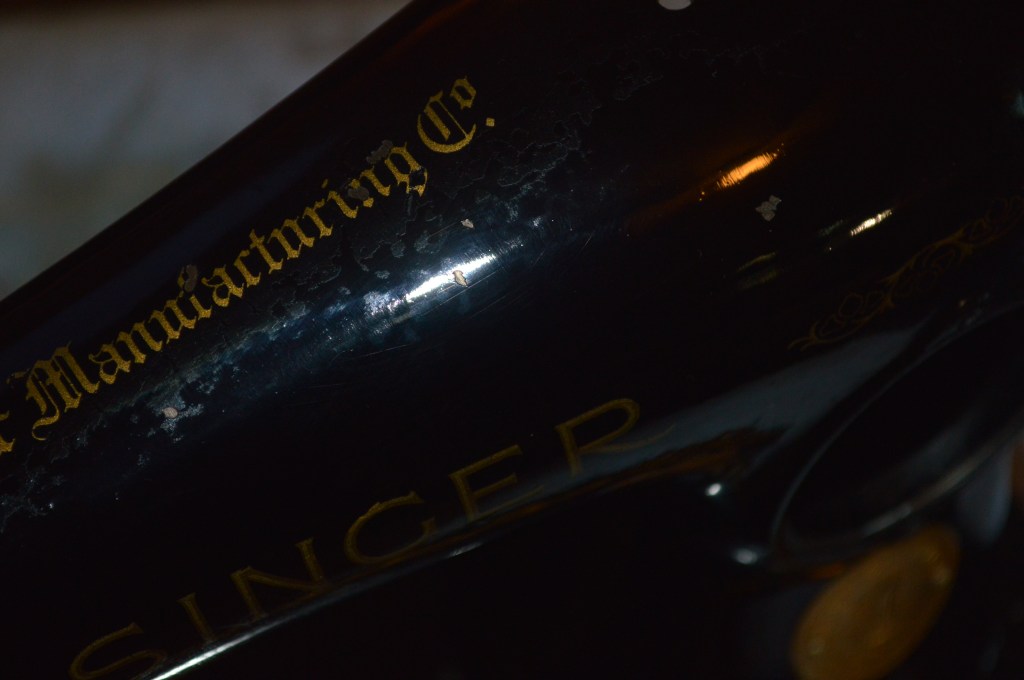

This restoration is interesting for a number of reasons. For me, one of the most interesting things about any machine I restore is it’s history. This machine is no different and researching its history was quite a chalenge. My customer purchased the machine from Shopgoodwill because of it’s name. It’s a Gimbels… and like many machines of it’s vintage, it’s a Singer class 15 clone made in Japan. But who made it? Gimbels did not manufacture sewing machines and like every other retailer would commission a Japanese sewing machine manufacturer to make their sewing machines and brand them with their name. This was a very common practice and is true for all retail store brands. What is unusual about this machine is that I cannot find another example like it. Good luck if you can, but where I can find examples of other Gimbels branded machines, this one is conspicuously absent. My customer explained that she bought the machine because her mother worked at Gimbels department store in New York city and she thought it would be great to have a machine sold by Gimbels to commerate the memory of her mother working there.

The Gimbels chain of retail stores found its roots in Indiana in 1842, they then moved to Milwaukee, and then to NYC. They closed their doors and were liquidated in 1987. In short, Gimbels had quite a heyday! Gimbels was a behemoth of a retail store with it’s largest store in New York city on 34th St. It’s rival competetor was Macy’s department store (located a short distance away down 34th St.). Most people are aware of the Macy’s Thanksgiving day parade in New York, but the Gimbel’s Thanksgiving Parade in Philadelphia was a grand parade as well.

I think it is a great story, and a great opportunity to restore this machine to as close to new condition as possible, and my customer is excited as well!

Restoration Plan

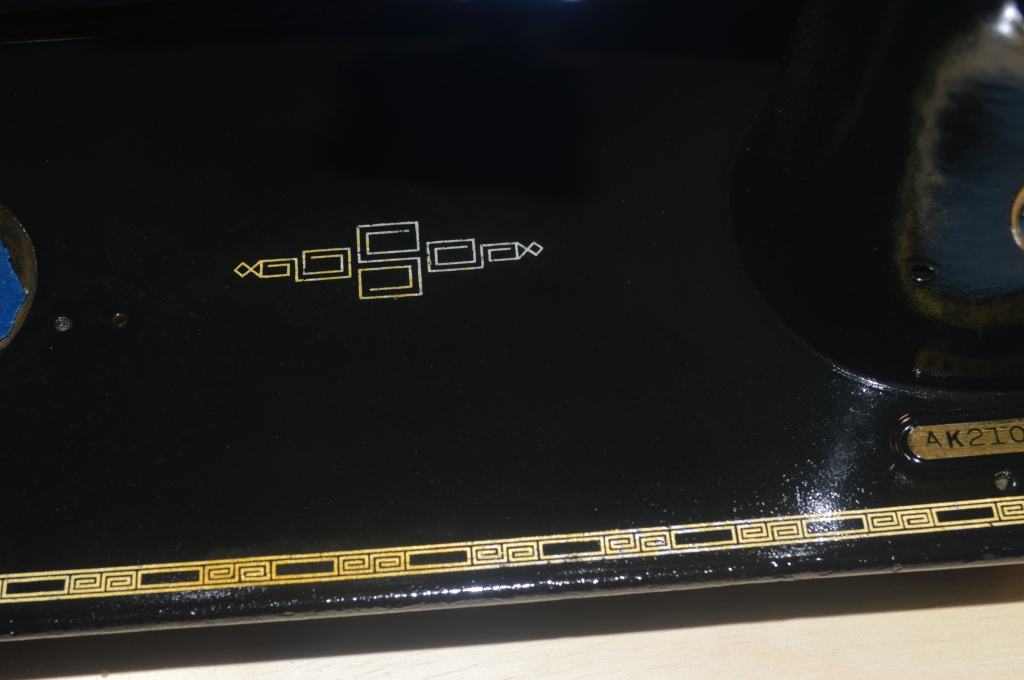

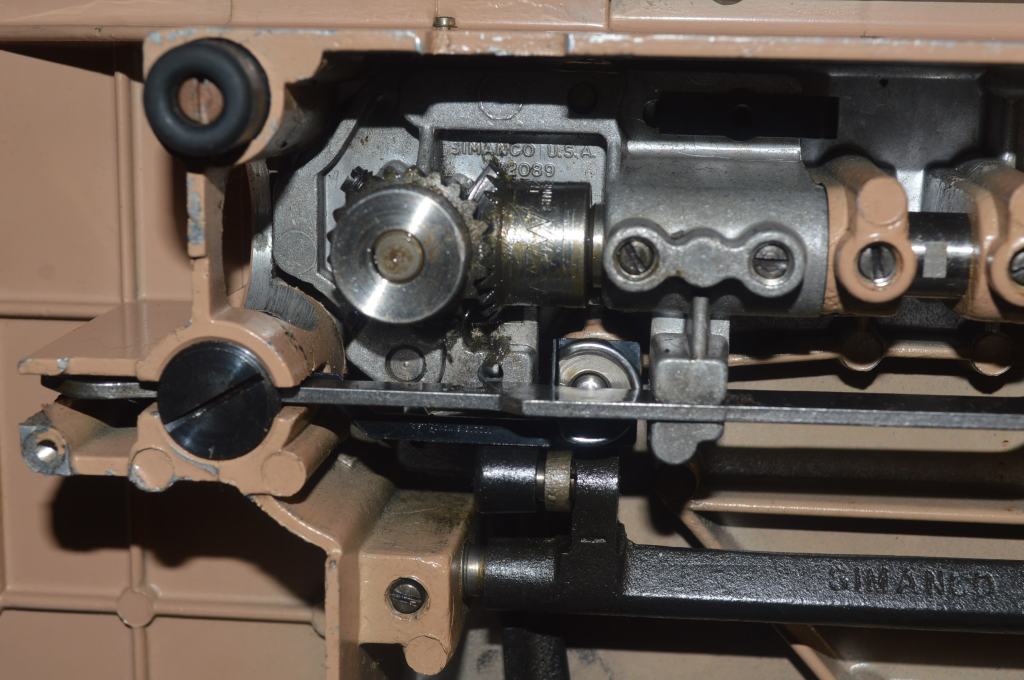

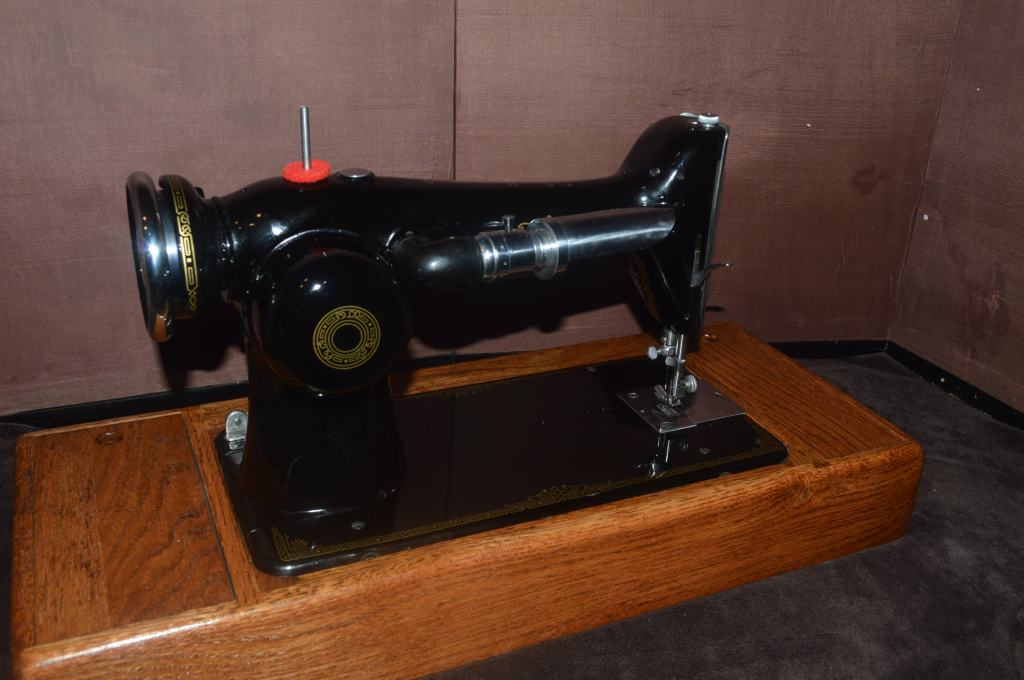

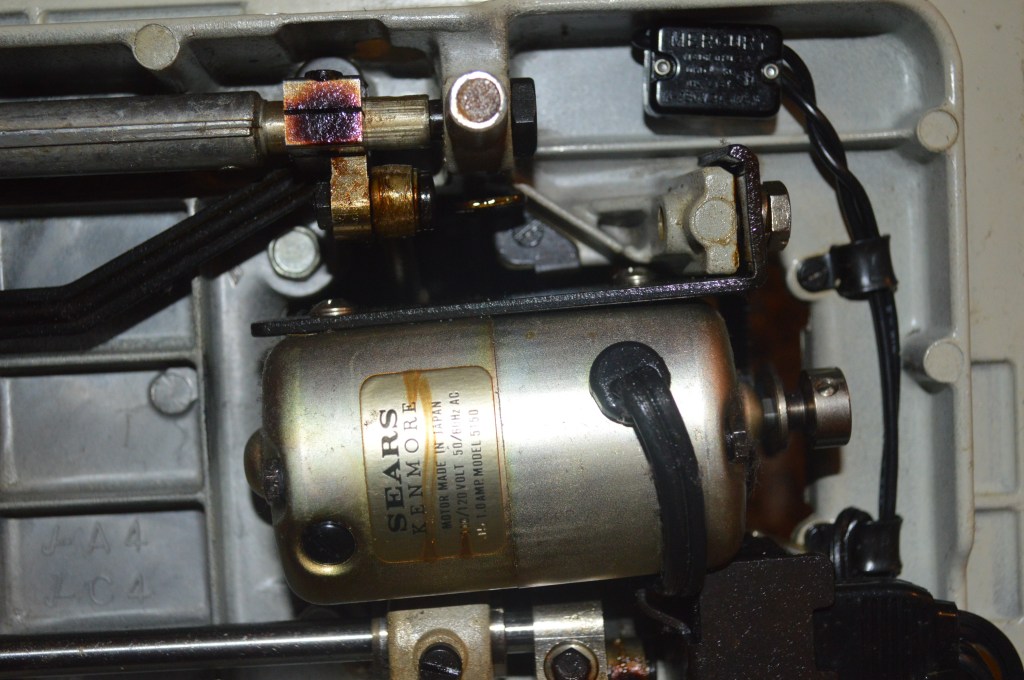

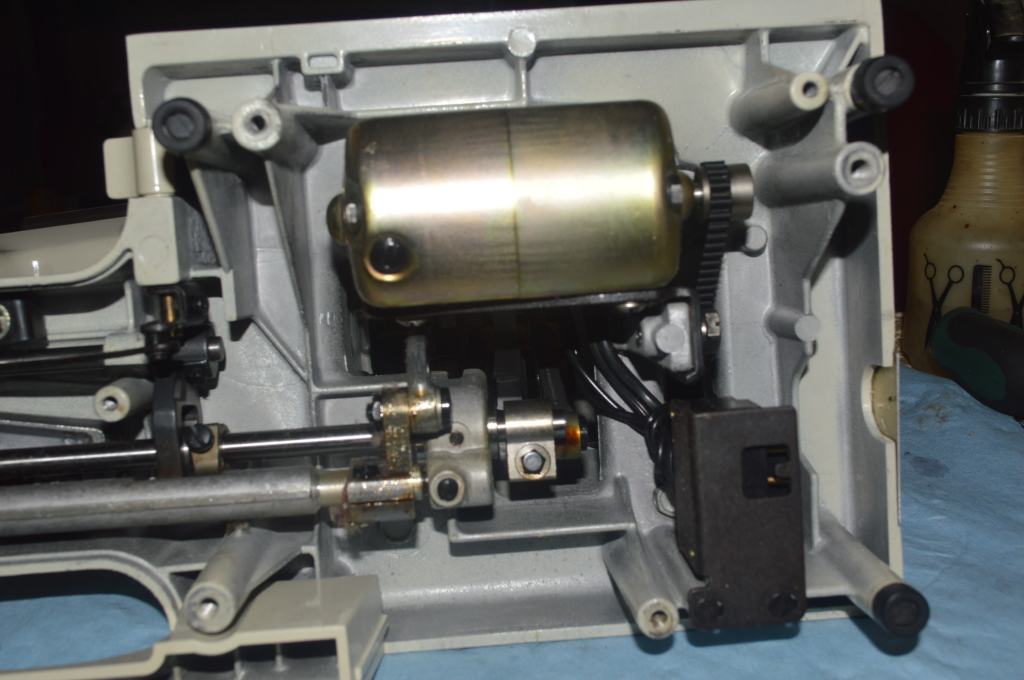

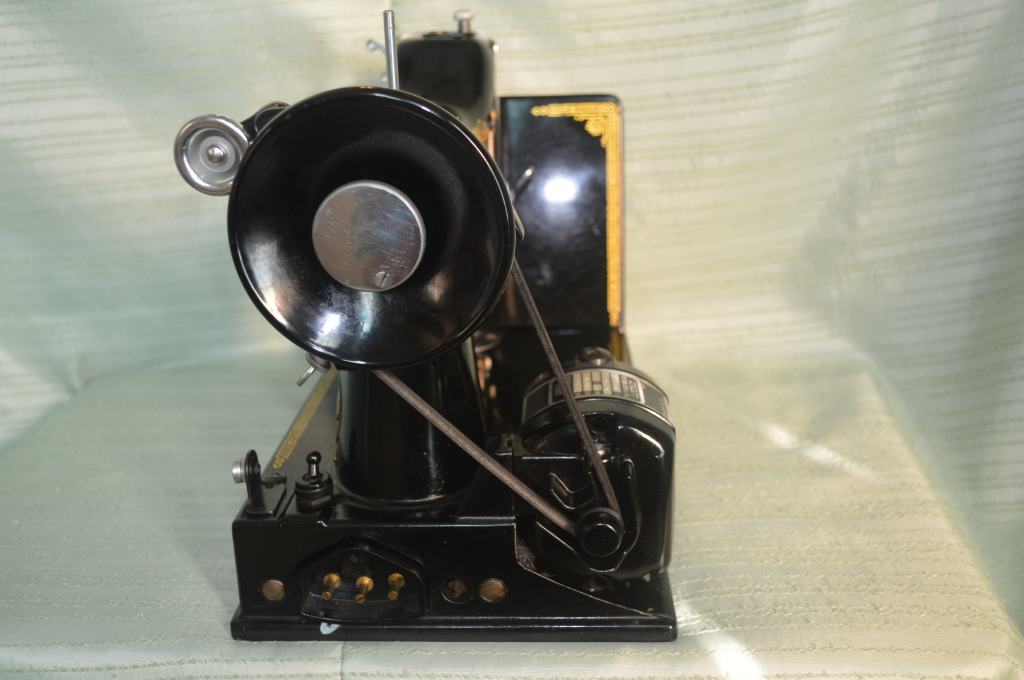

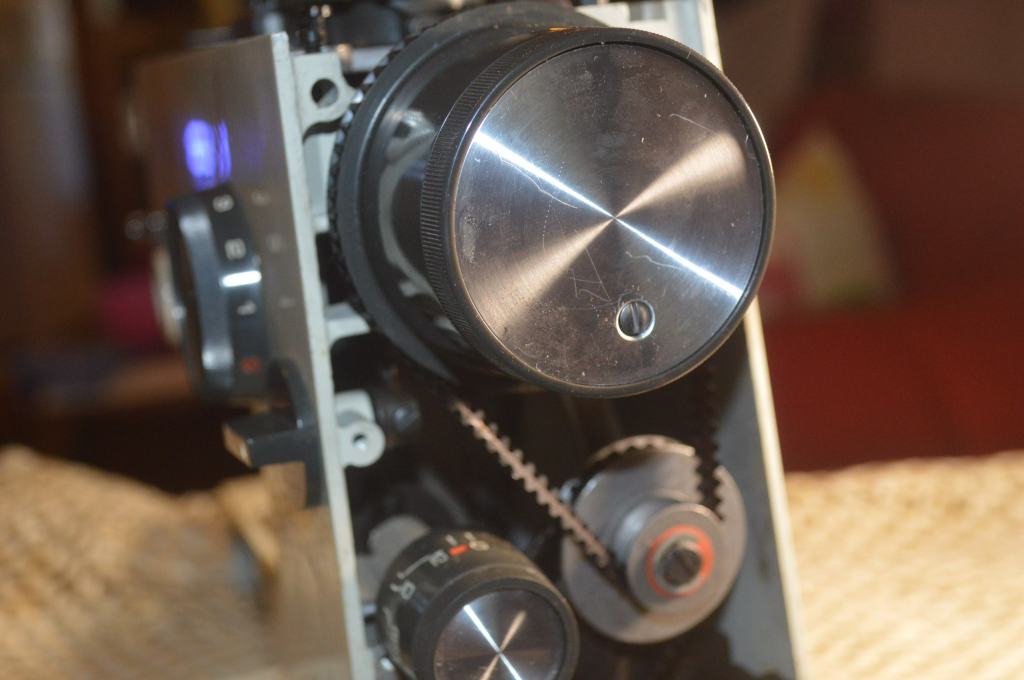

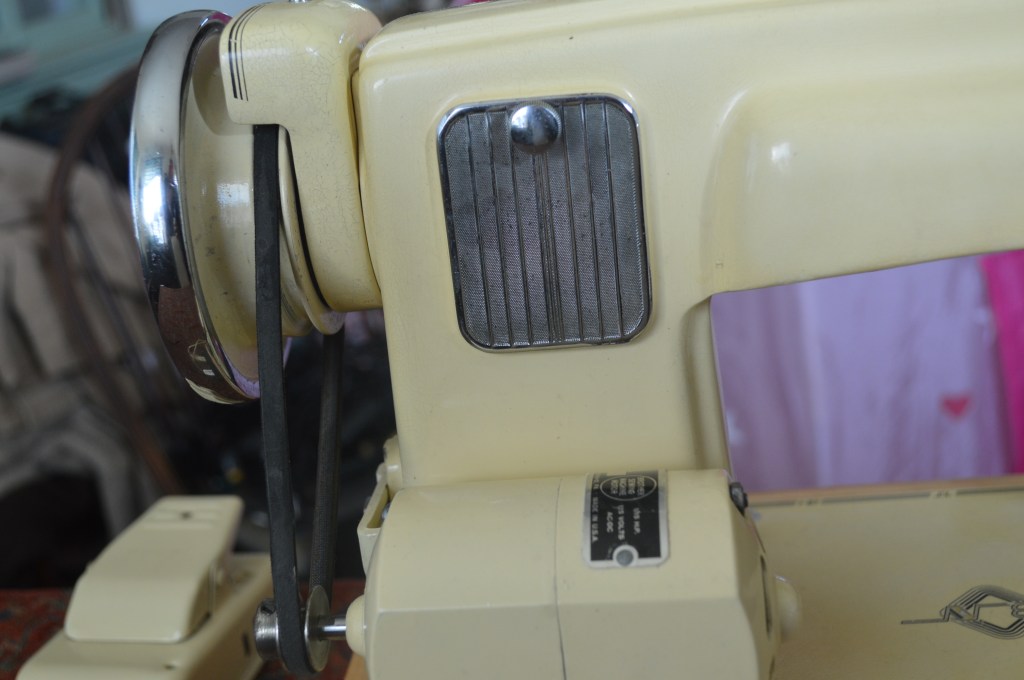

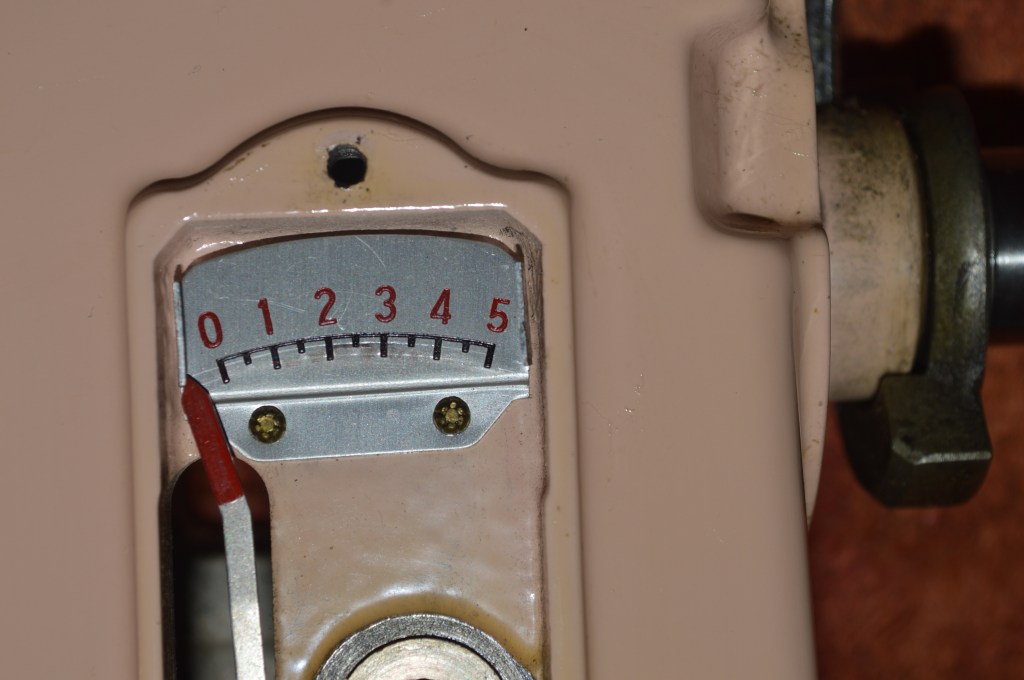

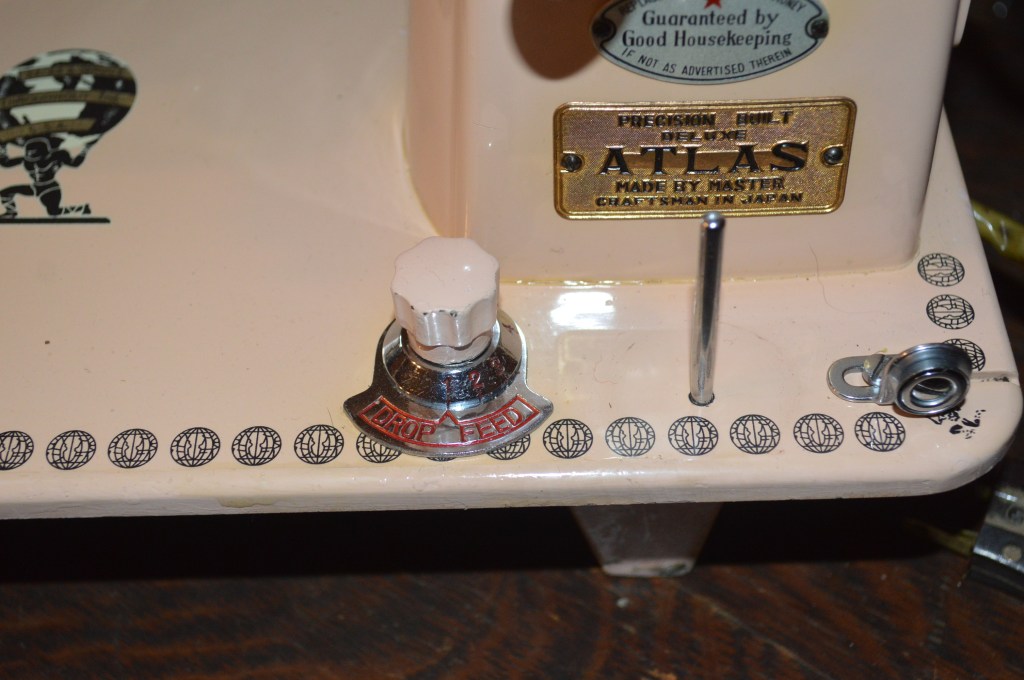

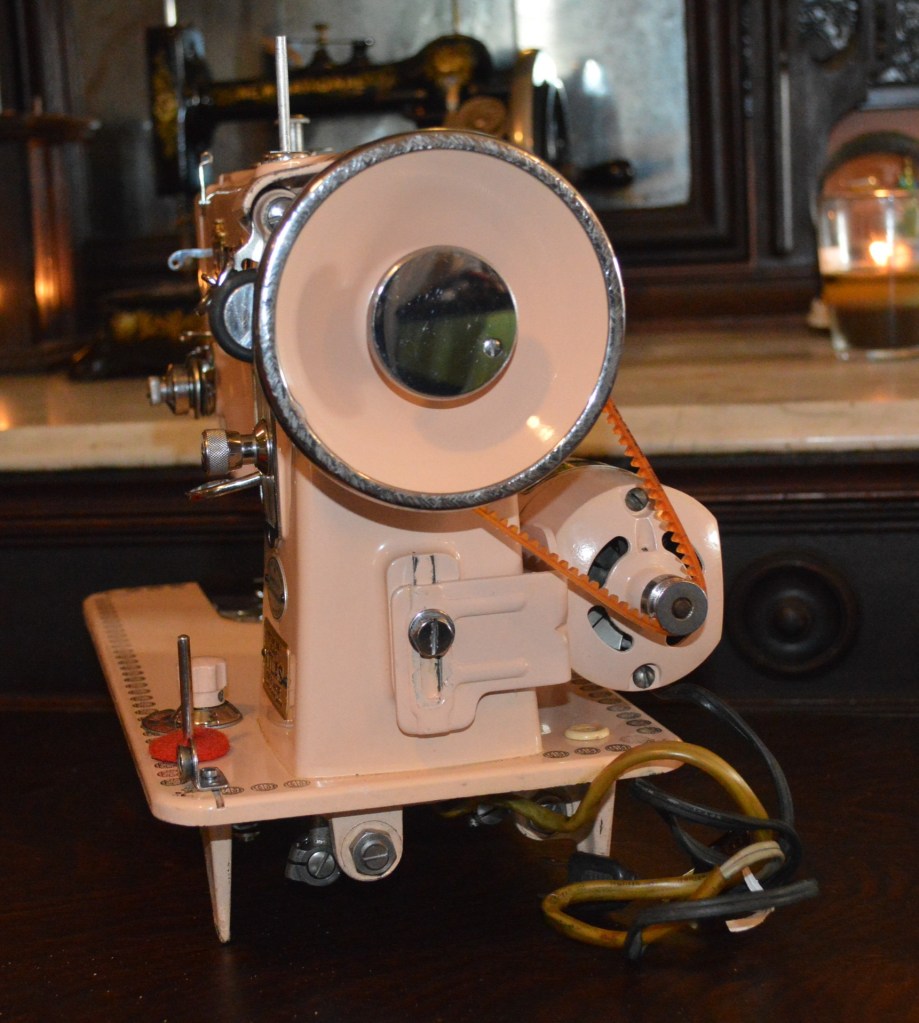

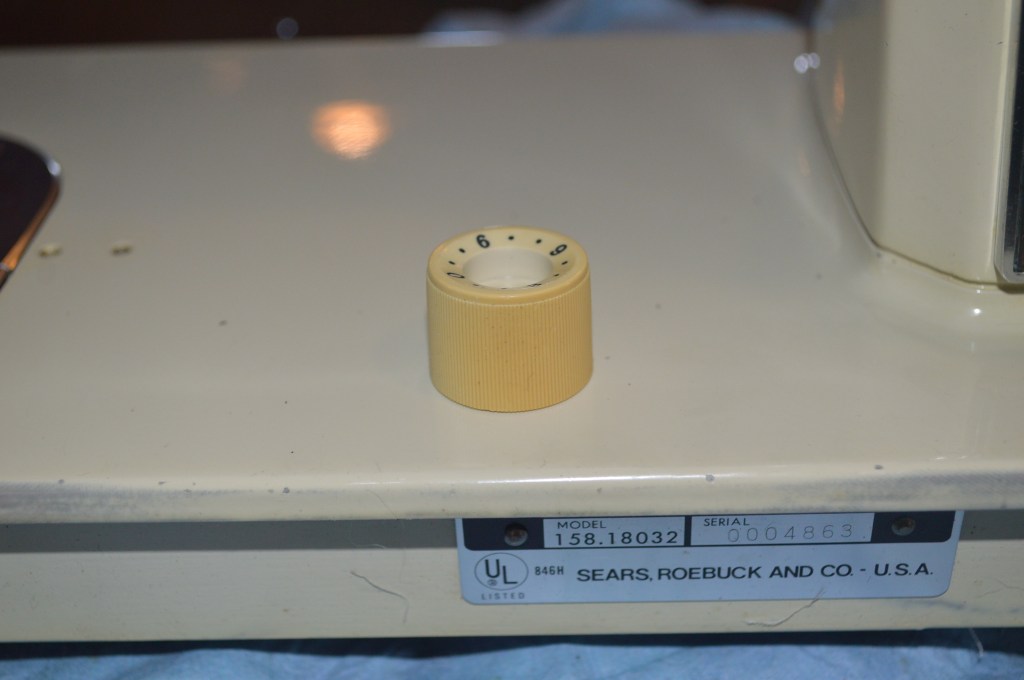

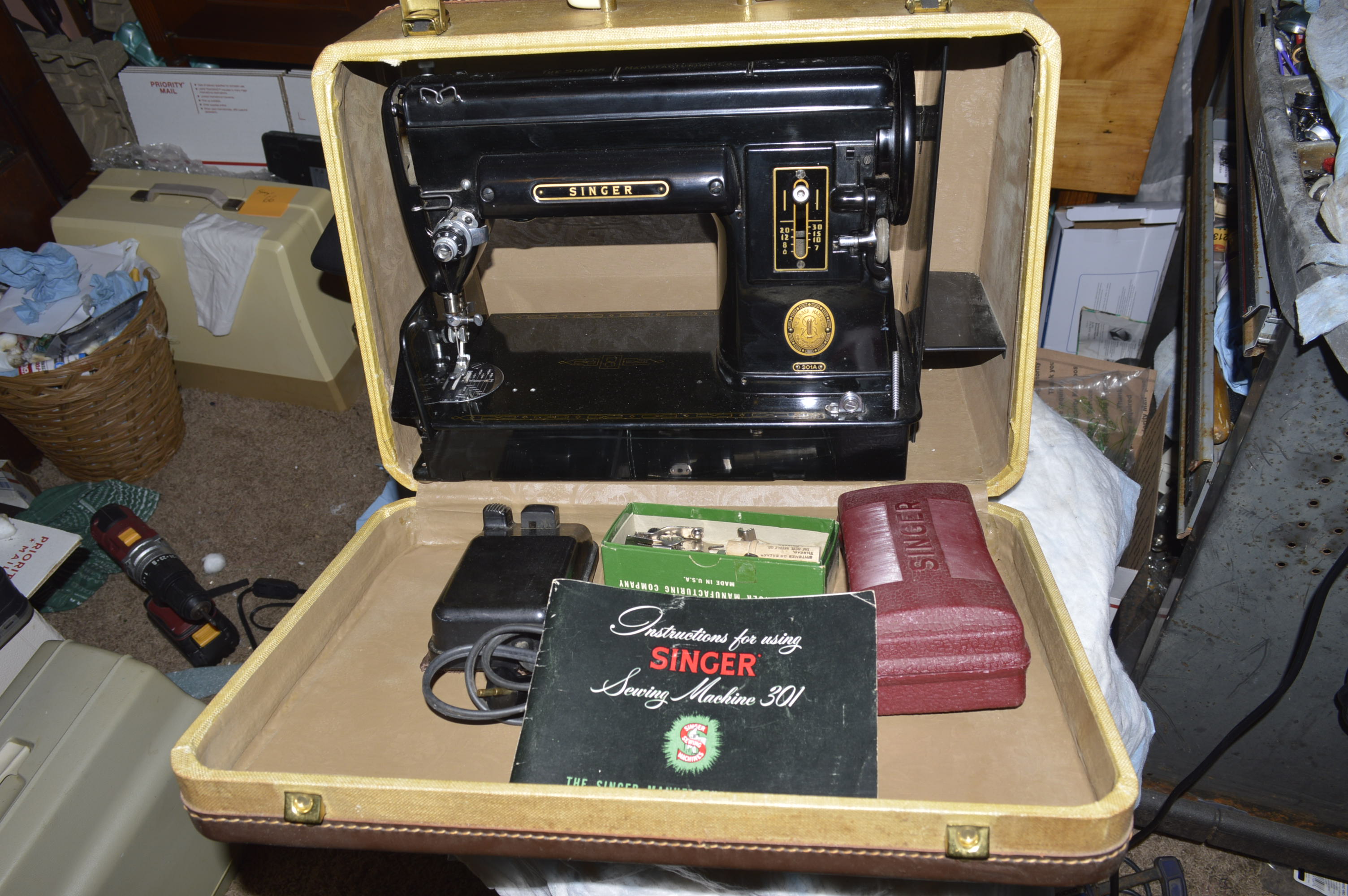

The model 1953 is a straight stitch machine. There are no identifying marks cast into the machine that give any clue clue to who manufactured the machine or when. The model 1953 might suggest that it was first introduced in 1953, but I couldn’t say with any certainty thats the year it was made. The motor on the machine is a Morse motor, and it may be an indication of the machine being manufactured by Morse. The stitch length controls and the top tension knob look similar to controls I have seen on Morse machines, but thats not enough to claim Morse was the manufacturer. The motor may have been replaced at some point in time and the controls also appear similar to machines Brother manufactured in the early 60’s. Unfortunately, I cannot conclusively provide a date or manufacturer for this machine., but If pressed for an answer, I would say it is likely made by Morse for Gimbels.

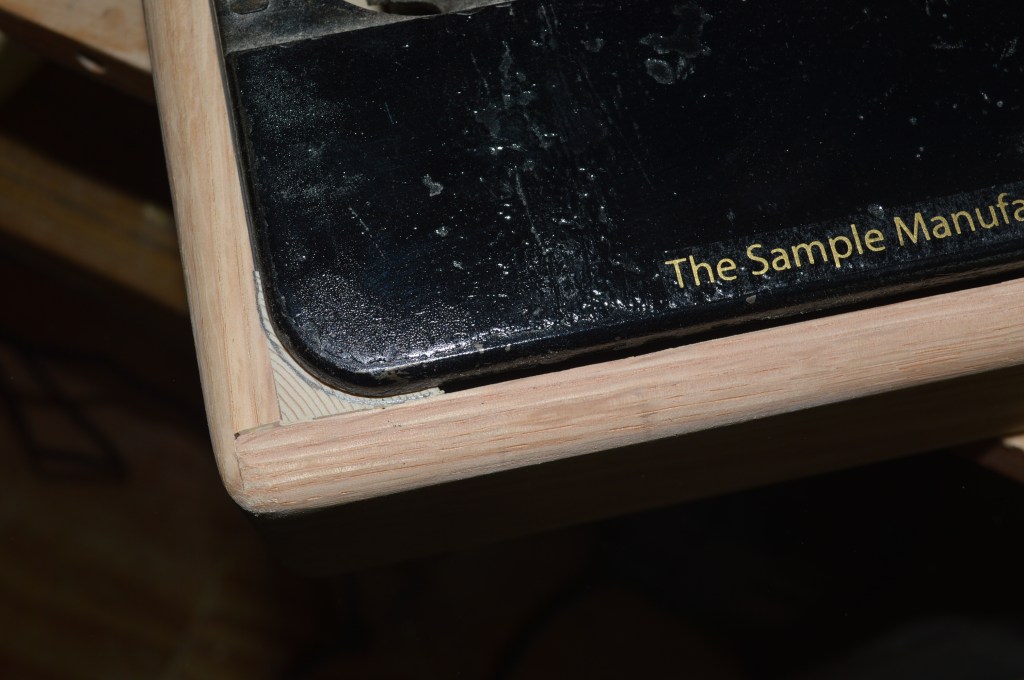

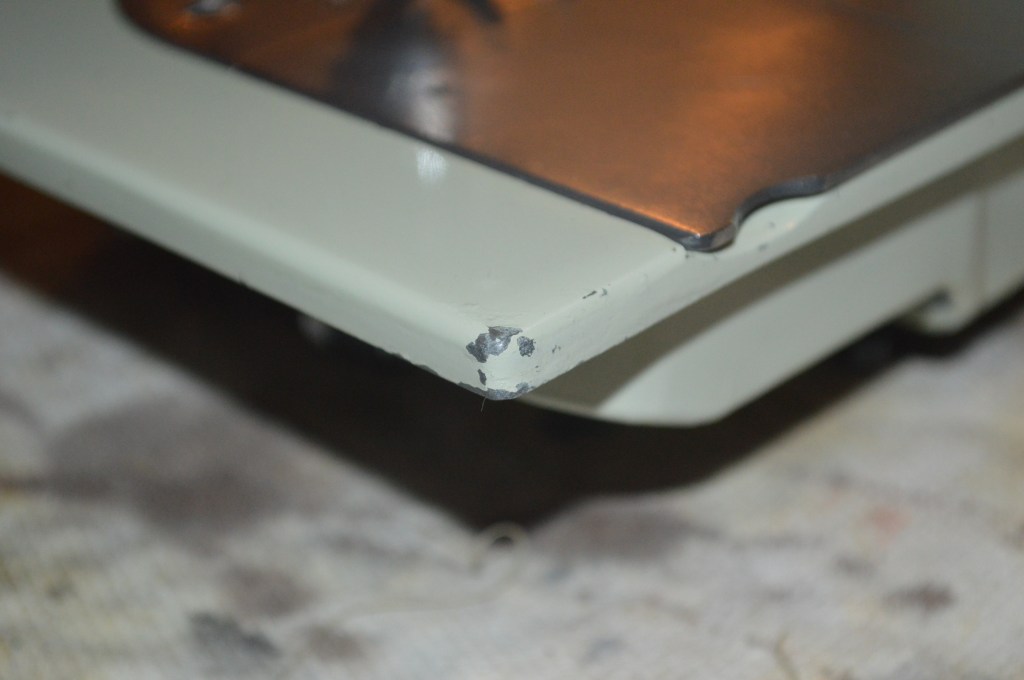

Part of the reason for this restoration is a sad story. As I said, my customer purchased this machine at a Shopgoodwill online auction. Shopgoodwill is a great place to find both common and unique sewing machines. At any given time, they can have 500 or more sewing machines for auction. I have purchased machines from them, and I have seen some rare and wonderful machines over the years. The only problem with purchasing a machine from them is that there is a high probability that it will be damaged in shipping… If it is in a case, the chance the case will be damaged by the machine smashing it or the spool pin punching thru the top… this is just my personal experience. I like Shopgoodwill and great bargains can be found there, but unless it is very desireable machine to me, I don’t source machines from them.

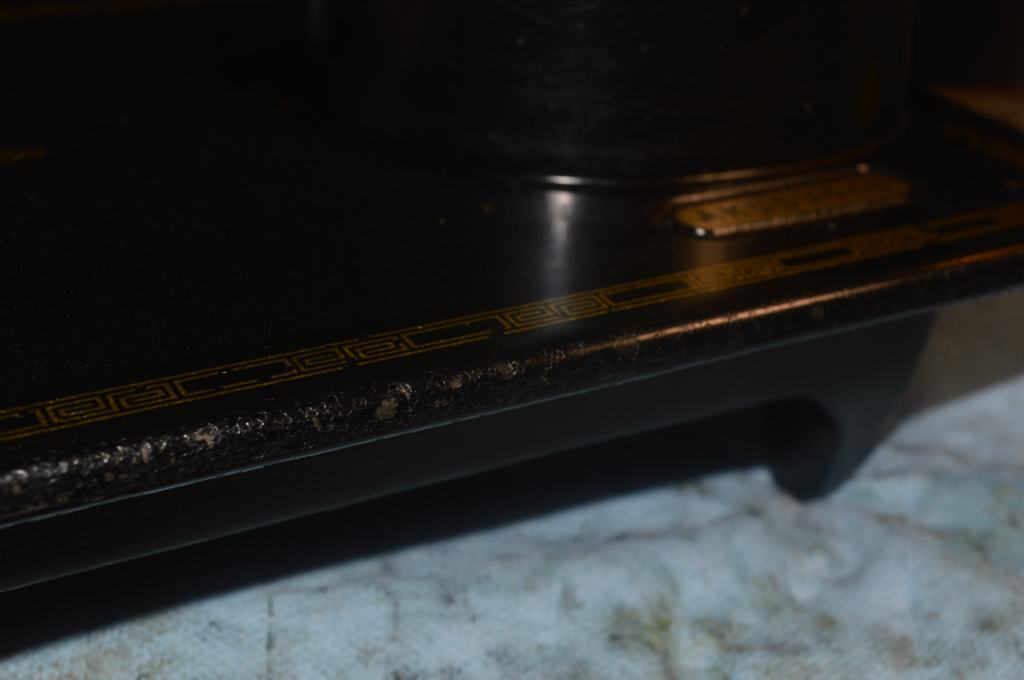

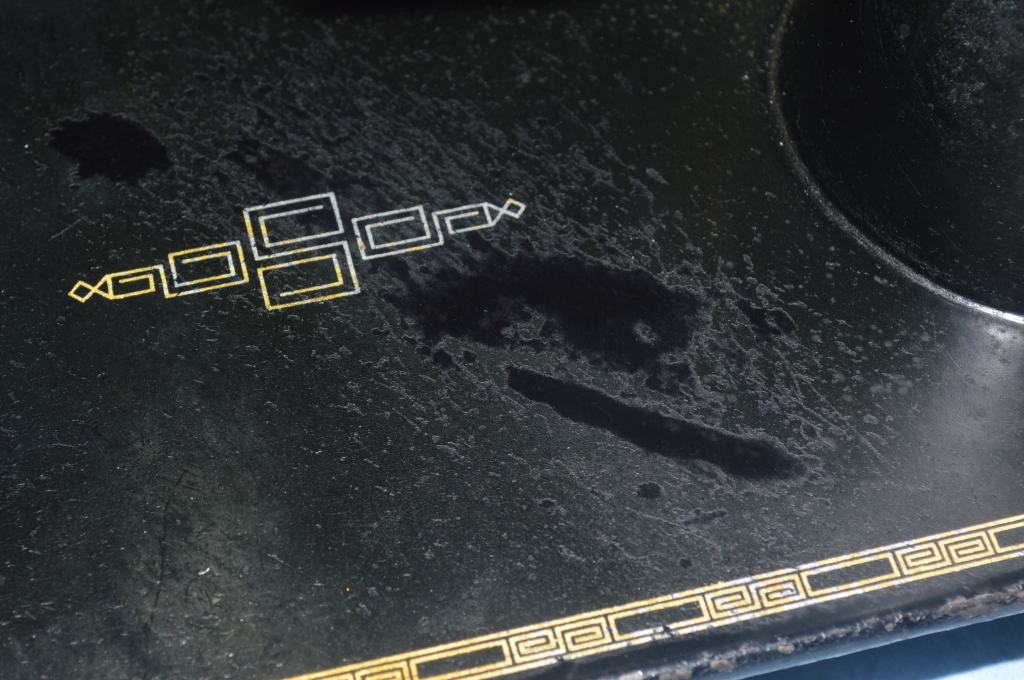

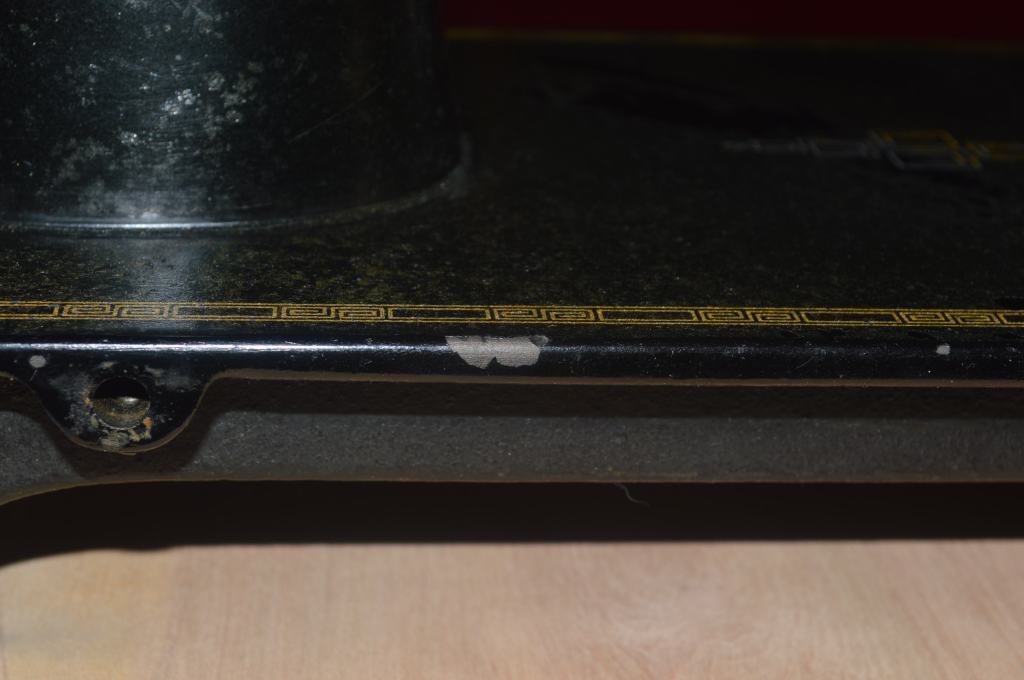

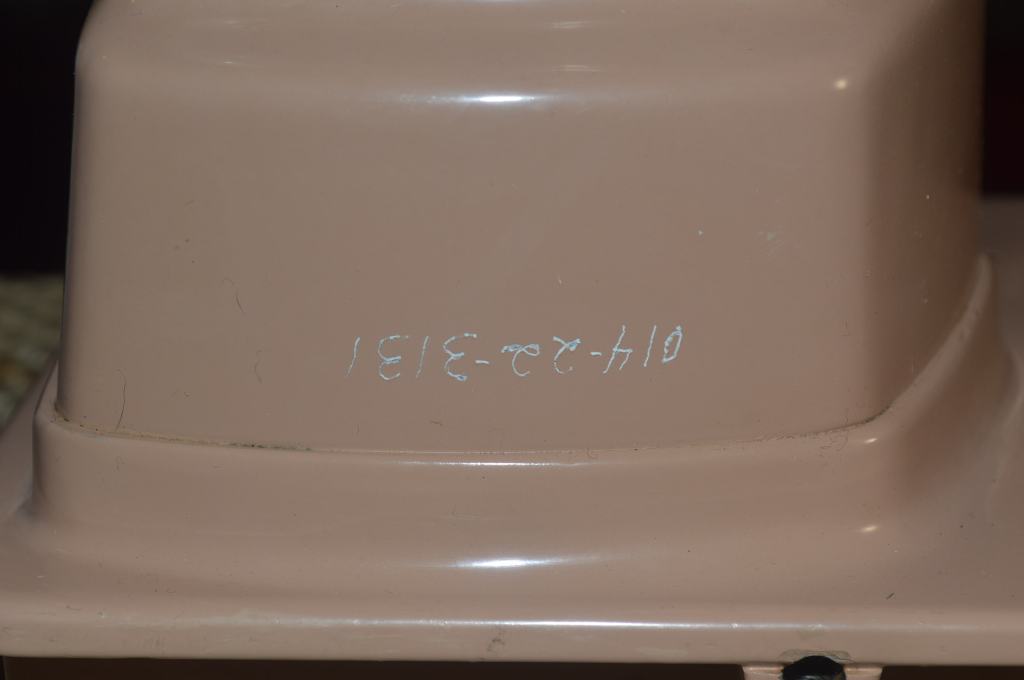

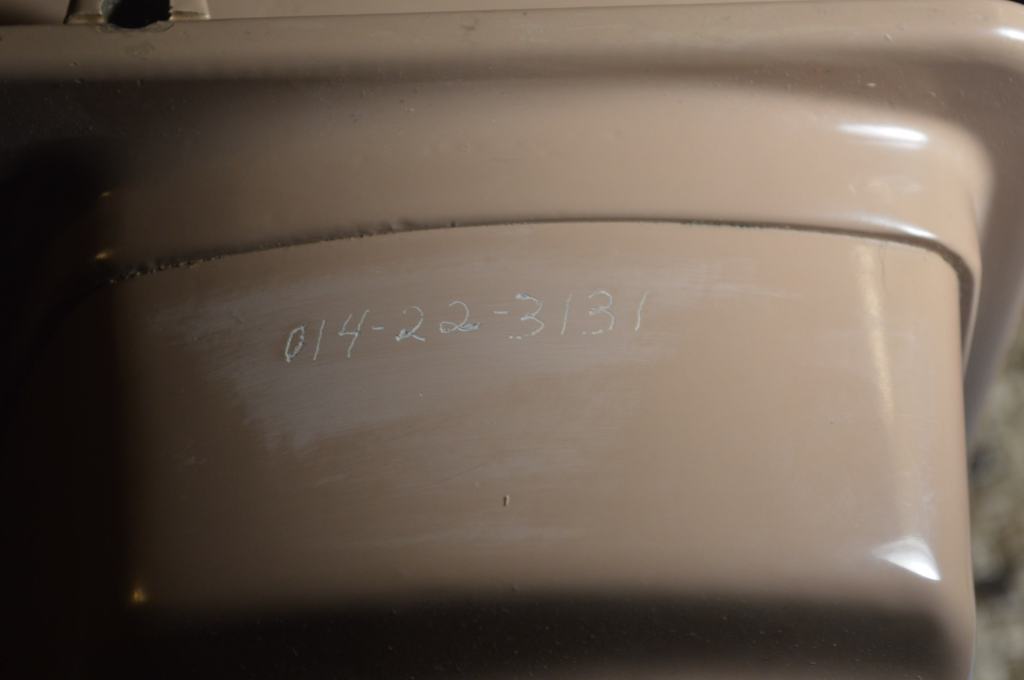

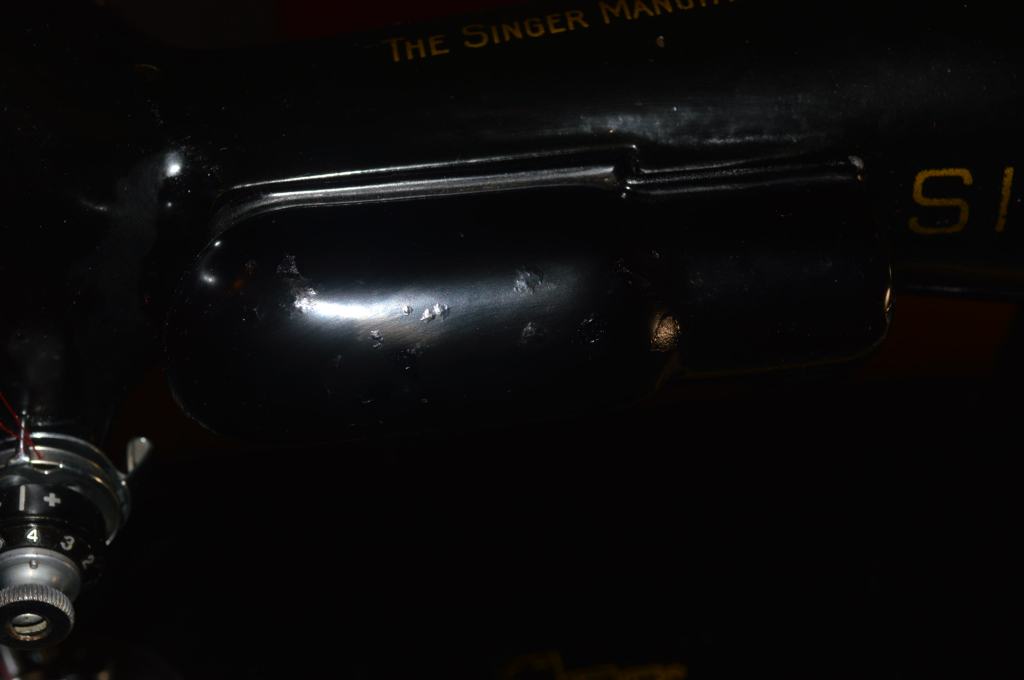

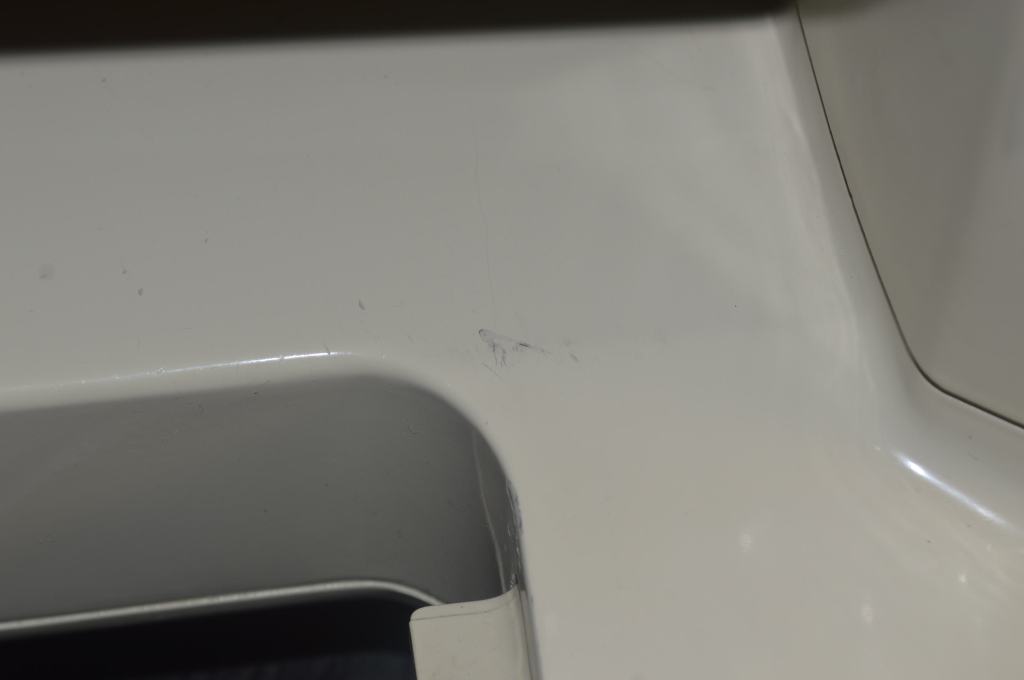

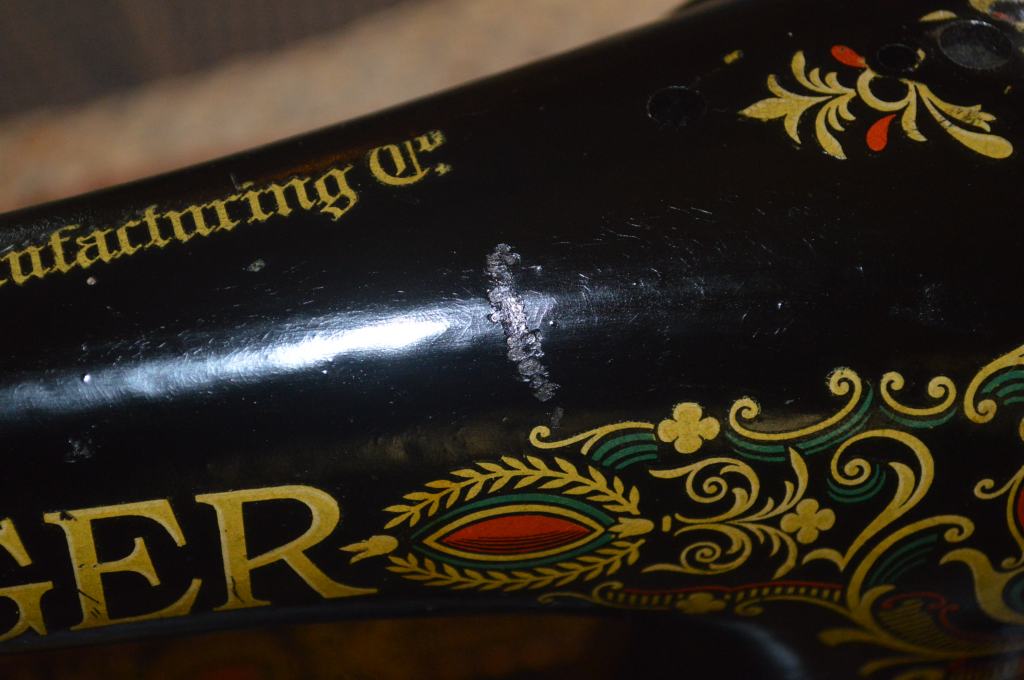

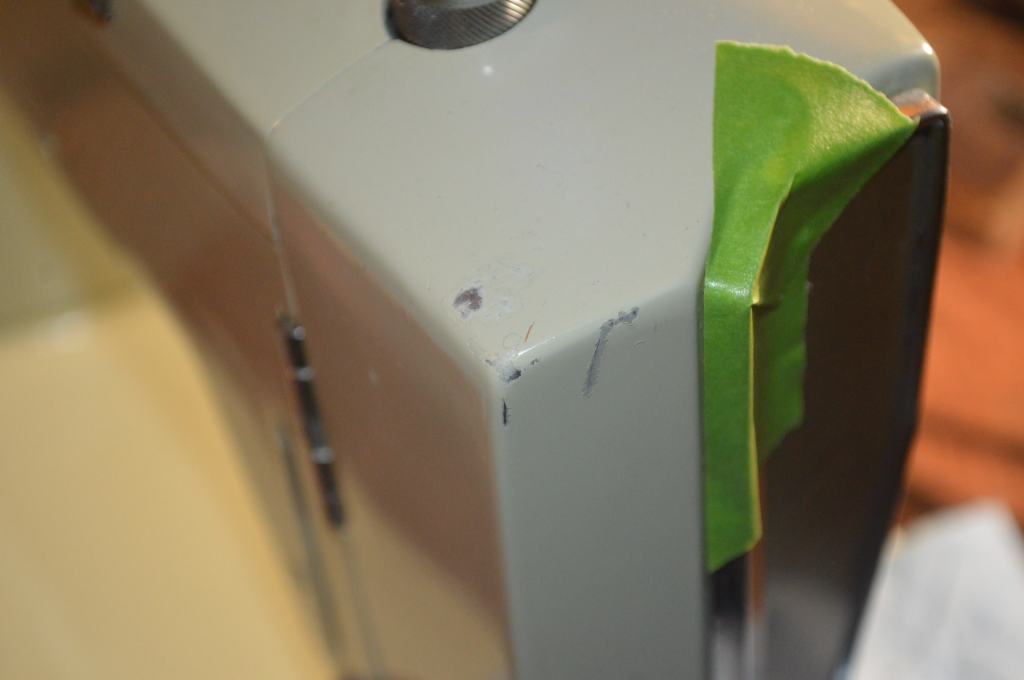

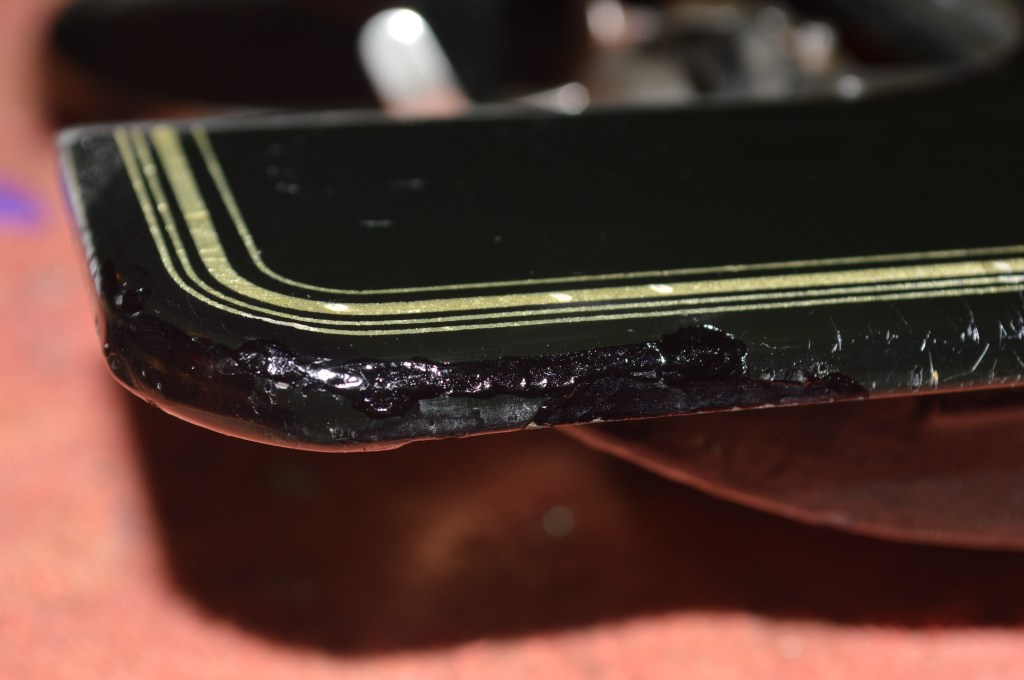

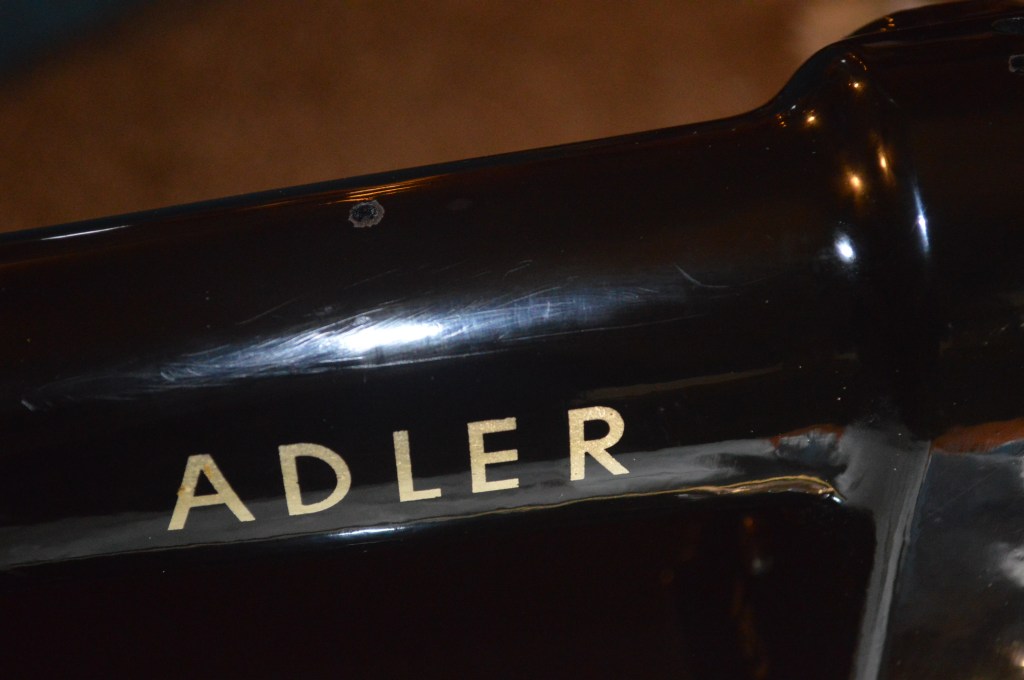

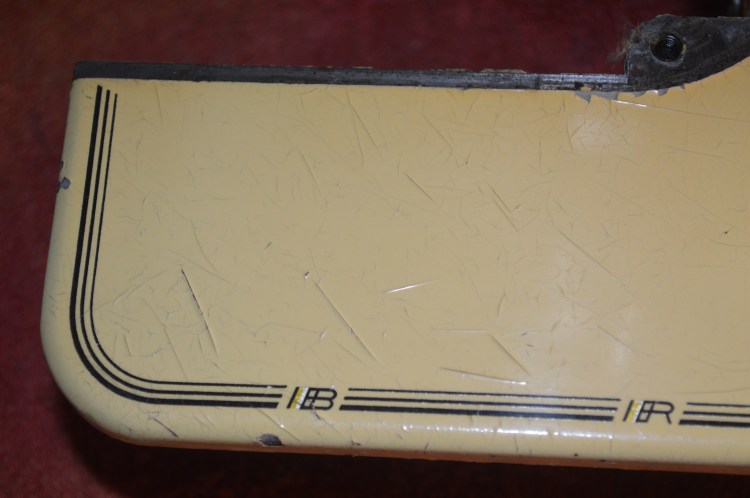

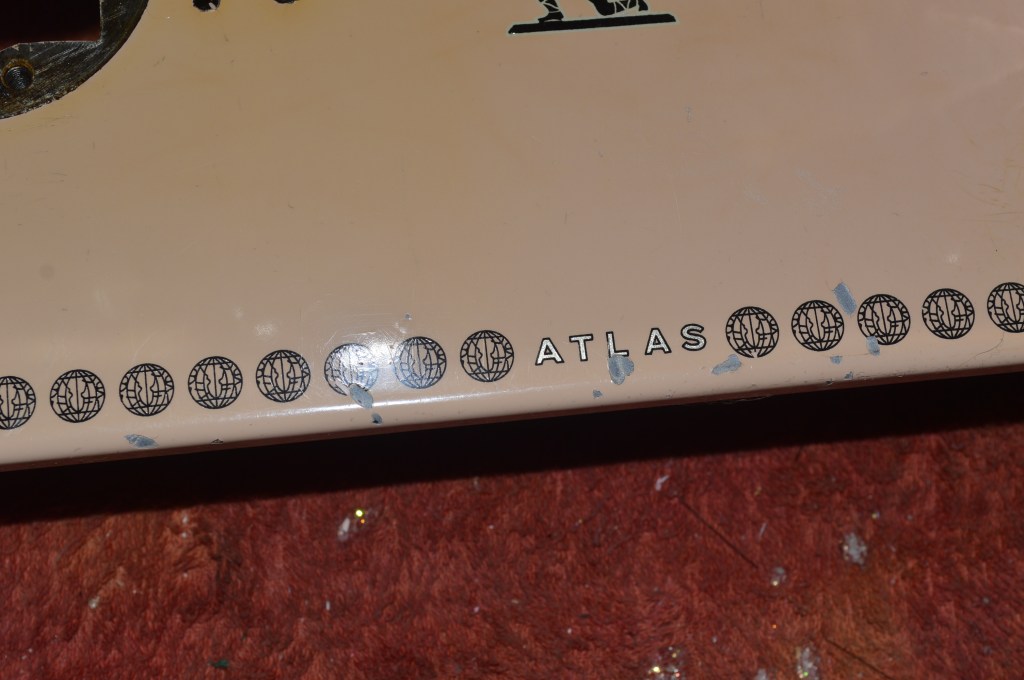

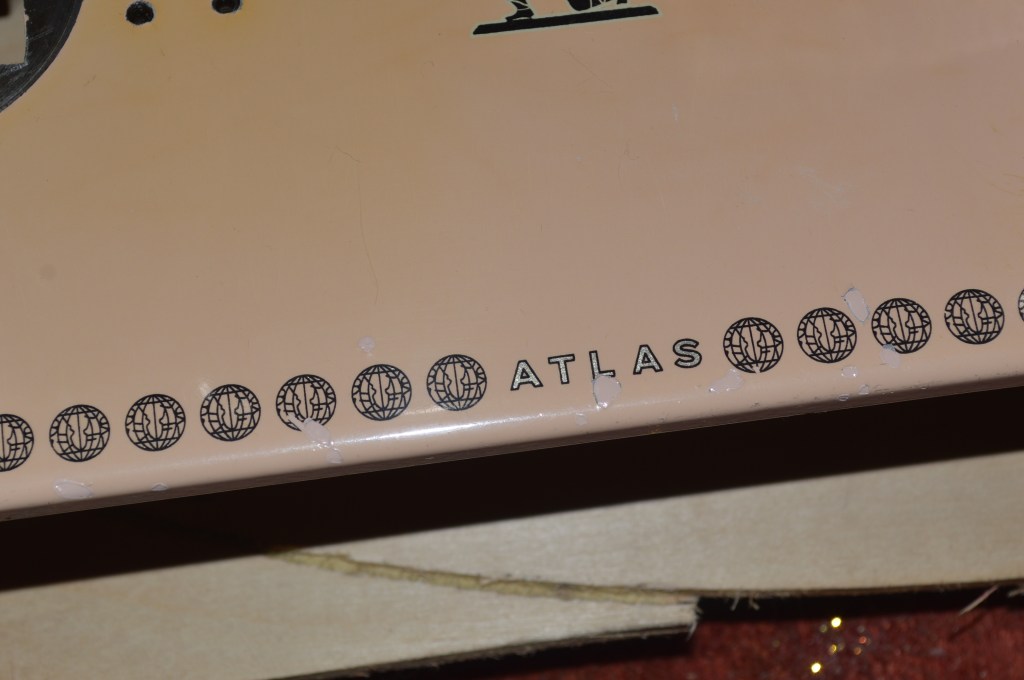

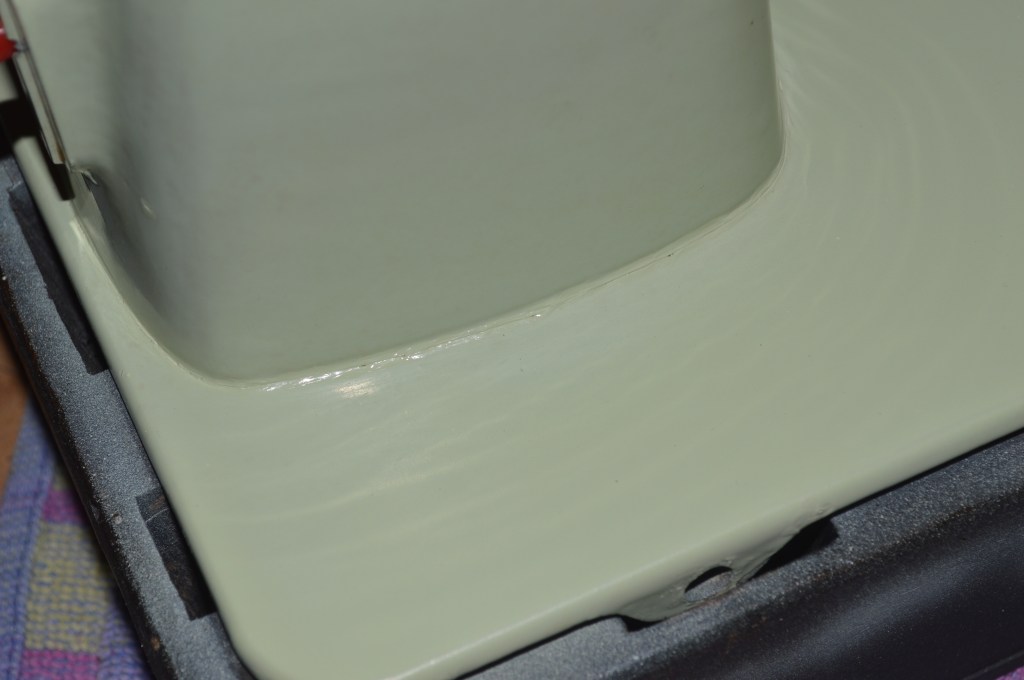

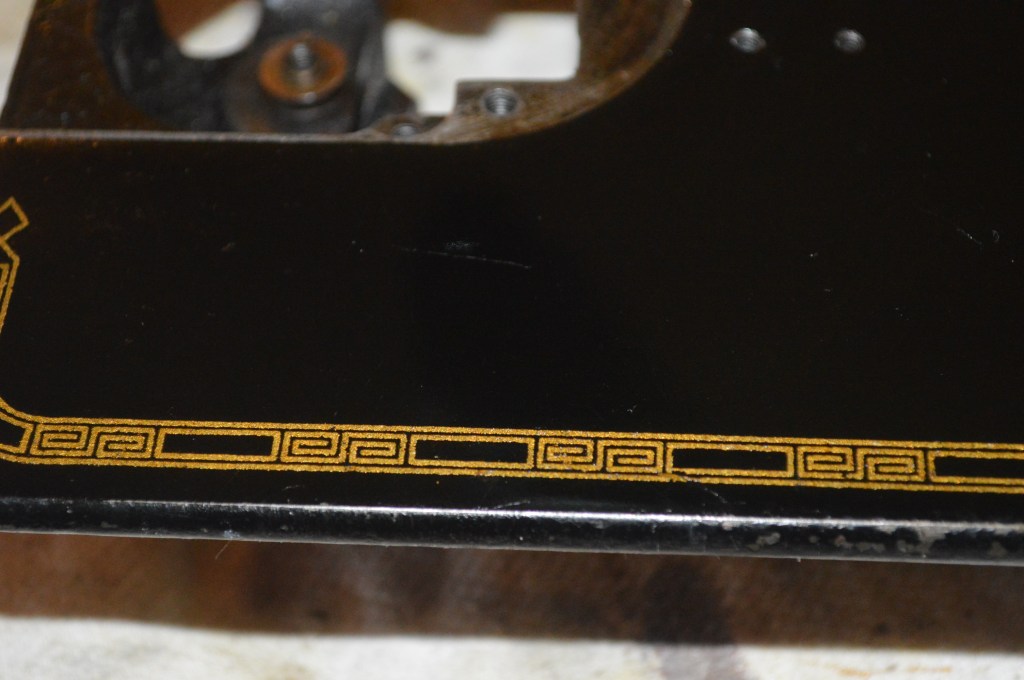

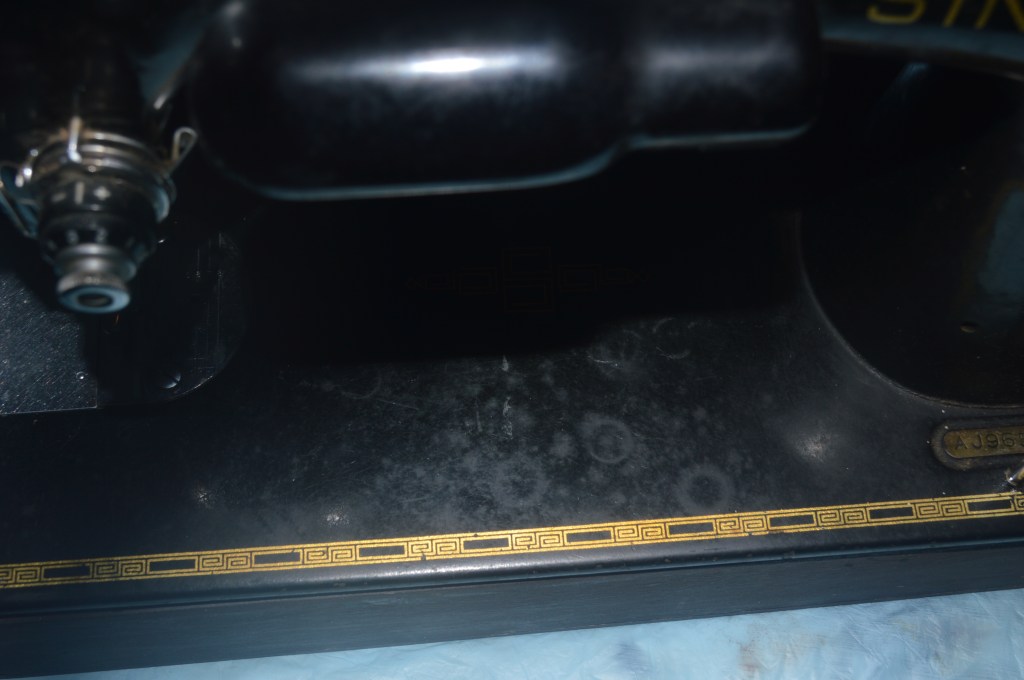

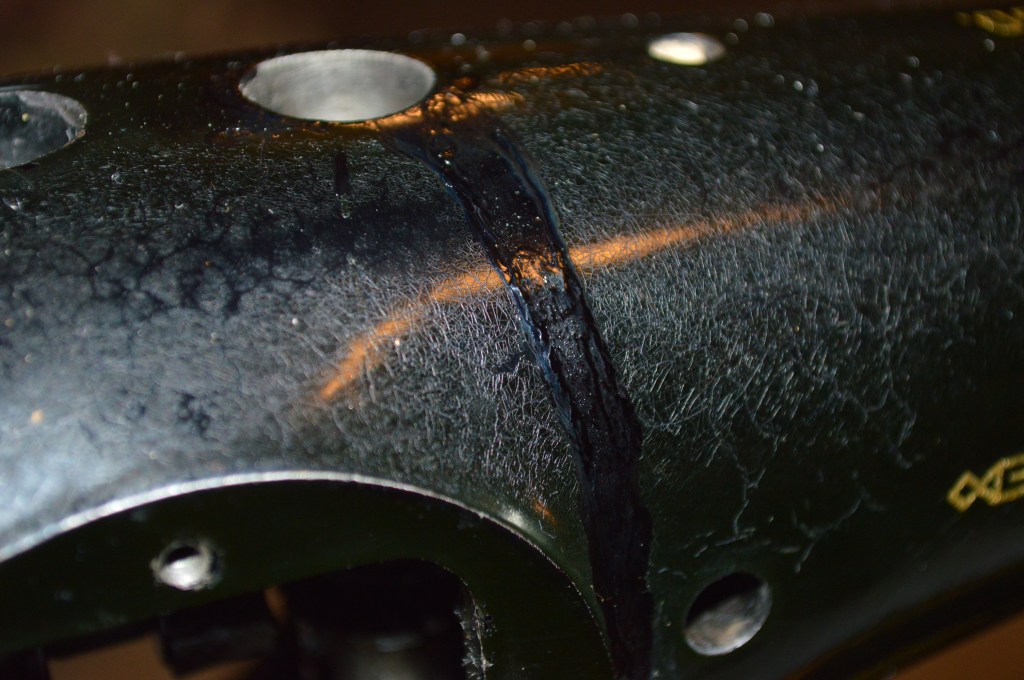

Unfortunately, this was the case when my customer got her machine. Please don’t take my experiences as a discourgement to purchase a machine from them, but do consider the possibility it may arrive with some damage. The machine listed was in beautiful condition, but because it was poorly packed with the metal foot controller in the box, the machines paint was severly scratched and gouged and the case was smashed. It arrived in quite a contrast to the picture of the machine listed where it was in beautiful condition.

Anyway, she wanted a base for her machine, and asked me if the paint scars could be repaired in a restoration. I explained that it could be made much less obvious with paint matching and she decided she wanted the machine to sew well and look good as well. A mechanical restoration was in order and I promised to do the best I could with the paint repair. Not normally included in a mechanical restoration, I don’t atempt extensive paint repairs, but it was important to make the most of the cosmetic repair for the best outcome.

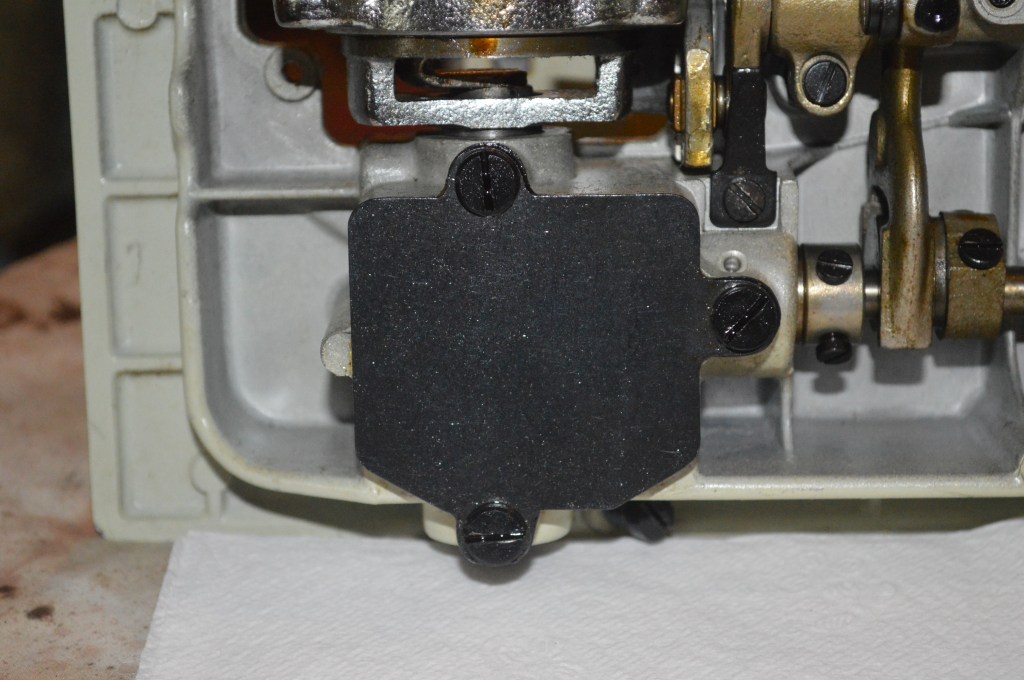

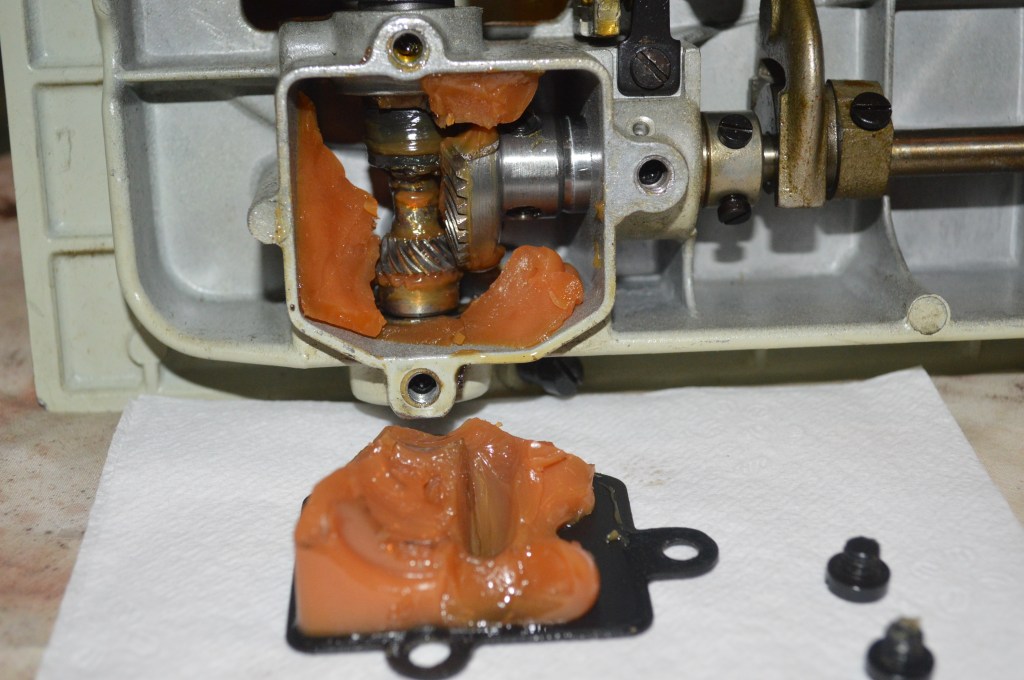

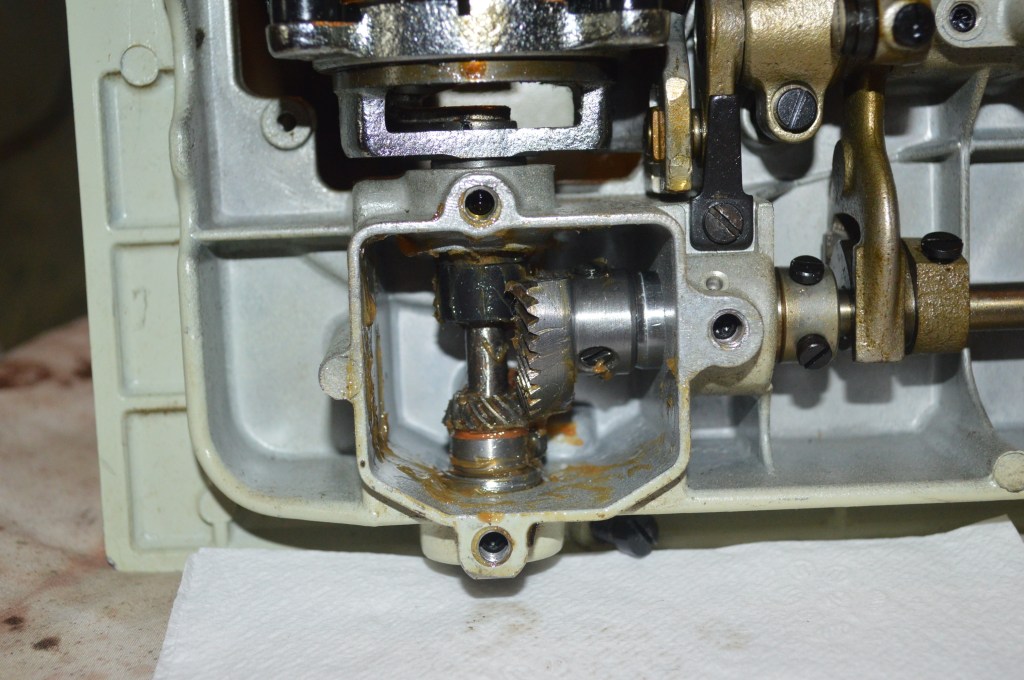

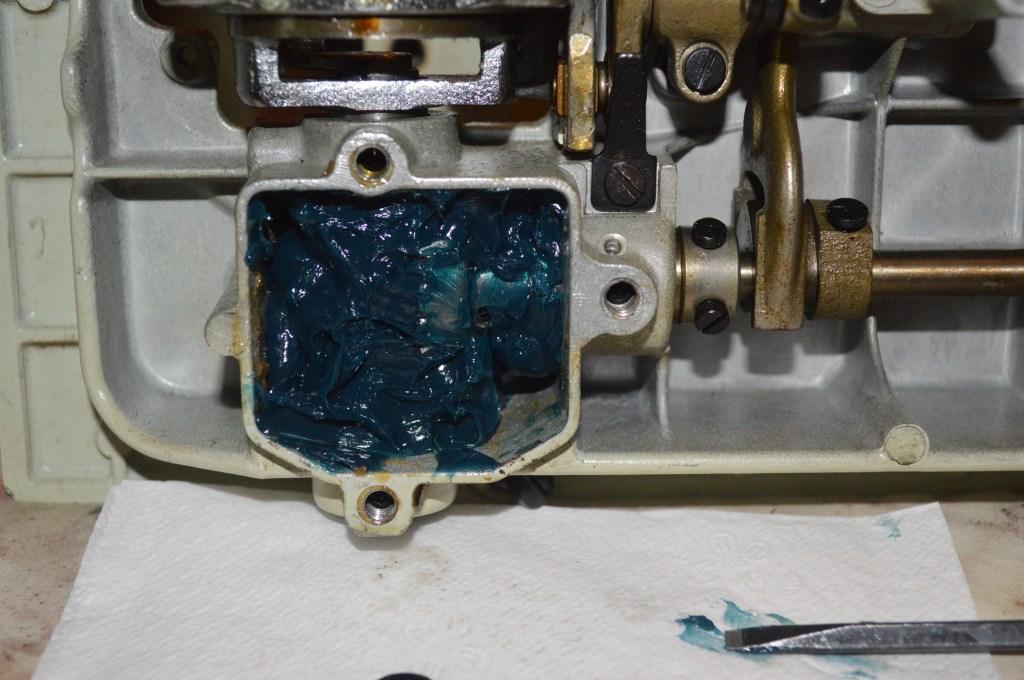

Mechanical Restoration

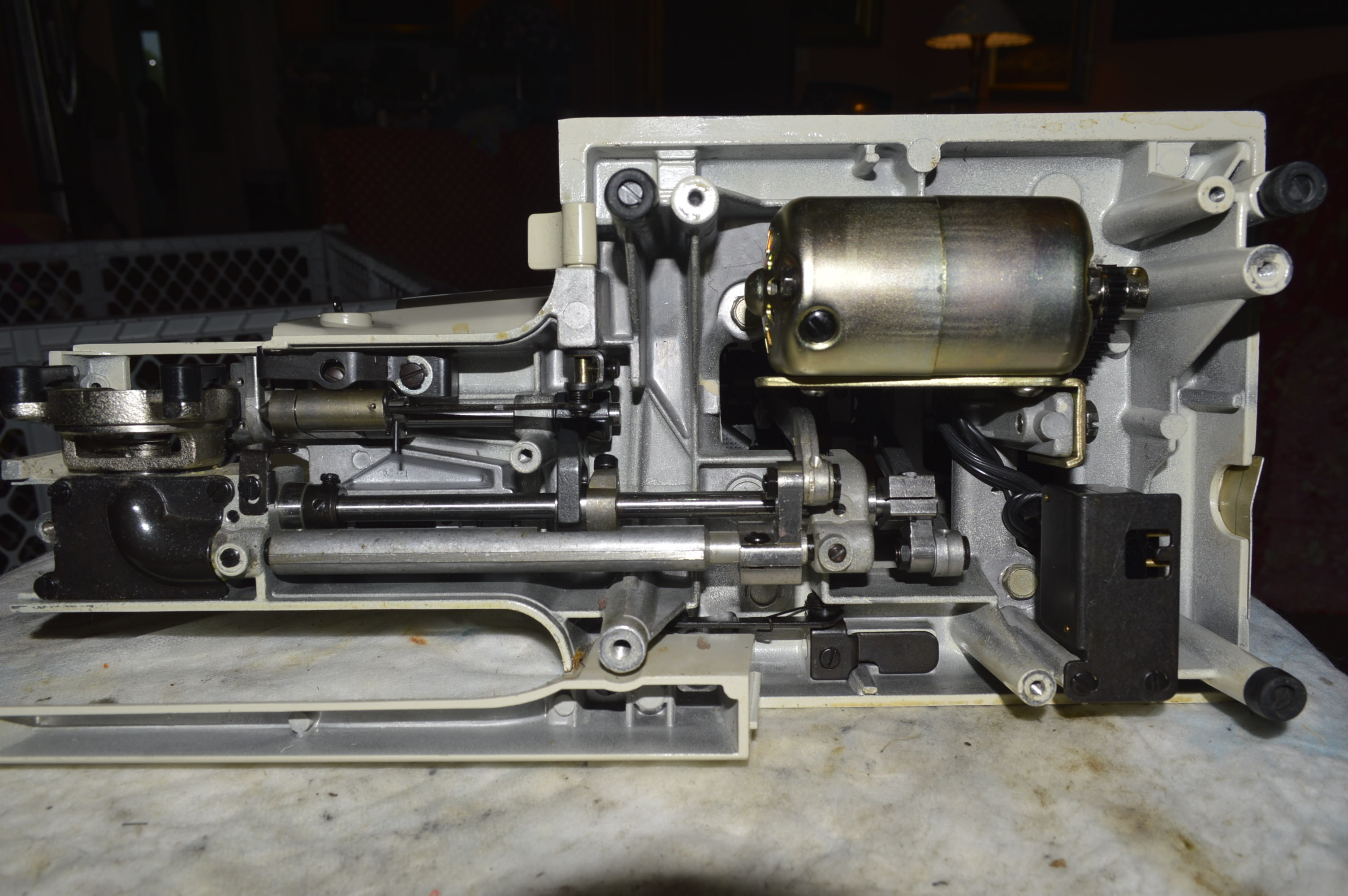

As usual, the machine will be disassembled to the greatest extent possible. Each piece will be cleaned and wire brushed to like new condition. The needle bar, presser foot bar, and the bottom bobbin hook shaft will be polished, and all of the chrome plated parts will be polished. The machine will be deep cleaned, and paint repairs will be made with custom mixed color matched paint. The motor will be disassembled, and for this machine, a replacement vintage foot controller will be provided and the main power wiring will be replaced. So, let me get started!

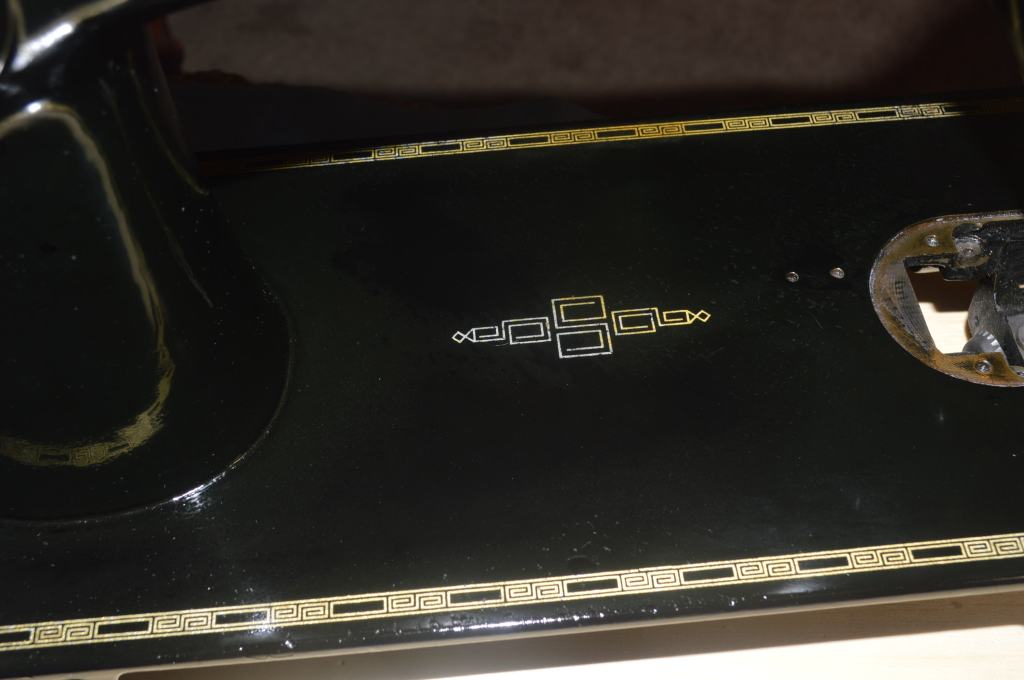

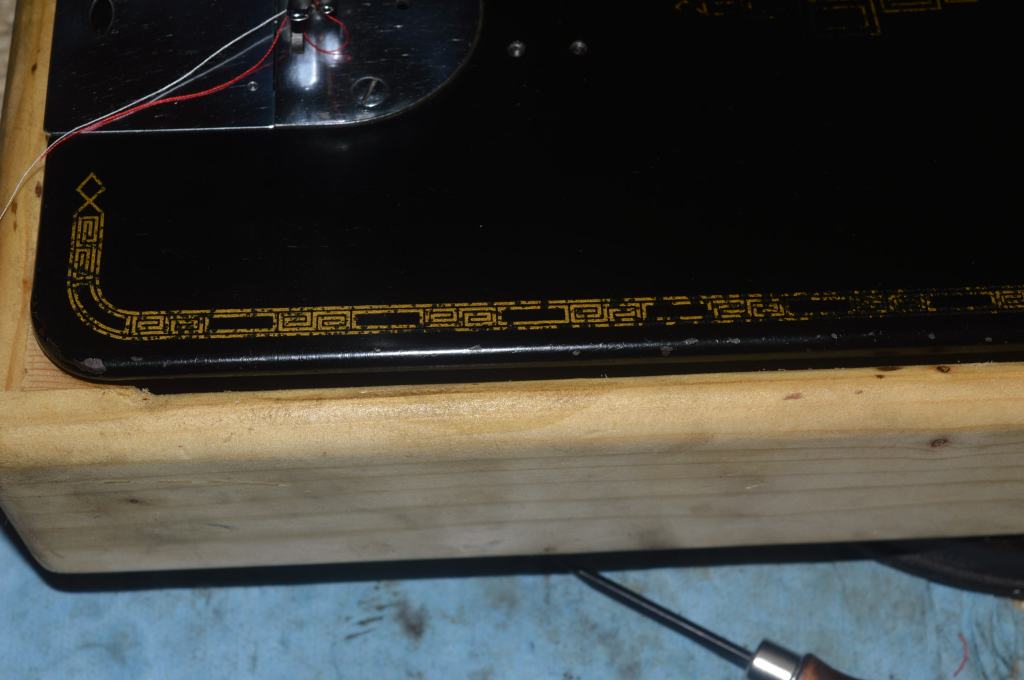

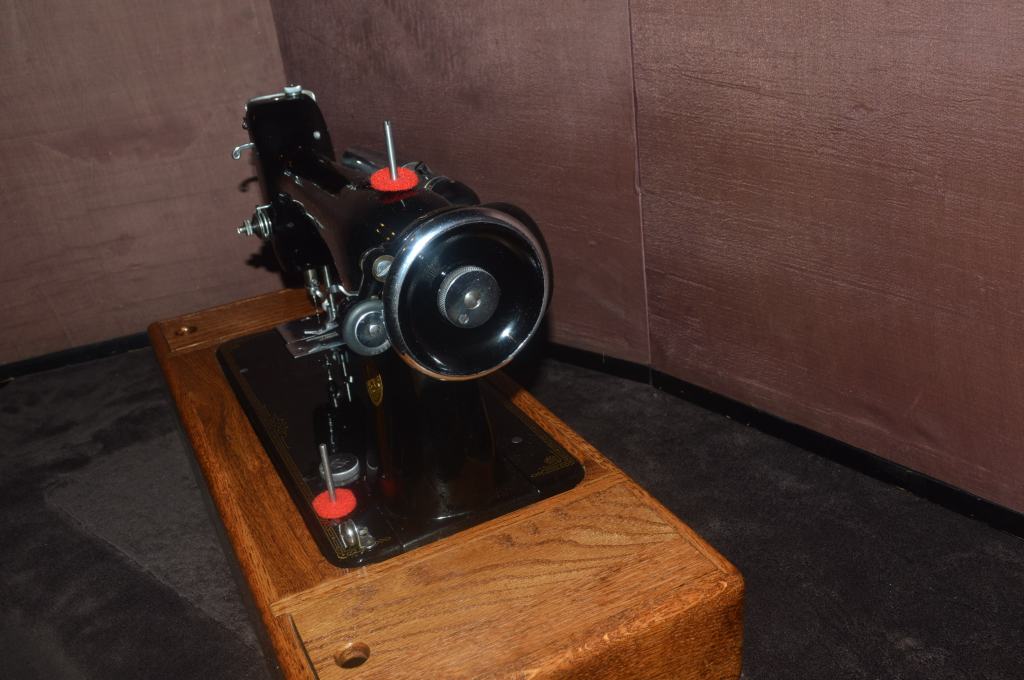

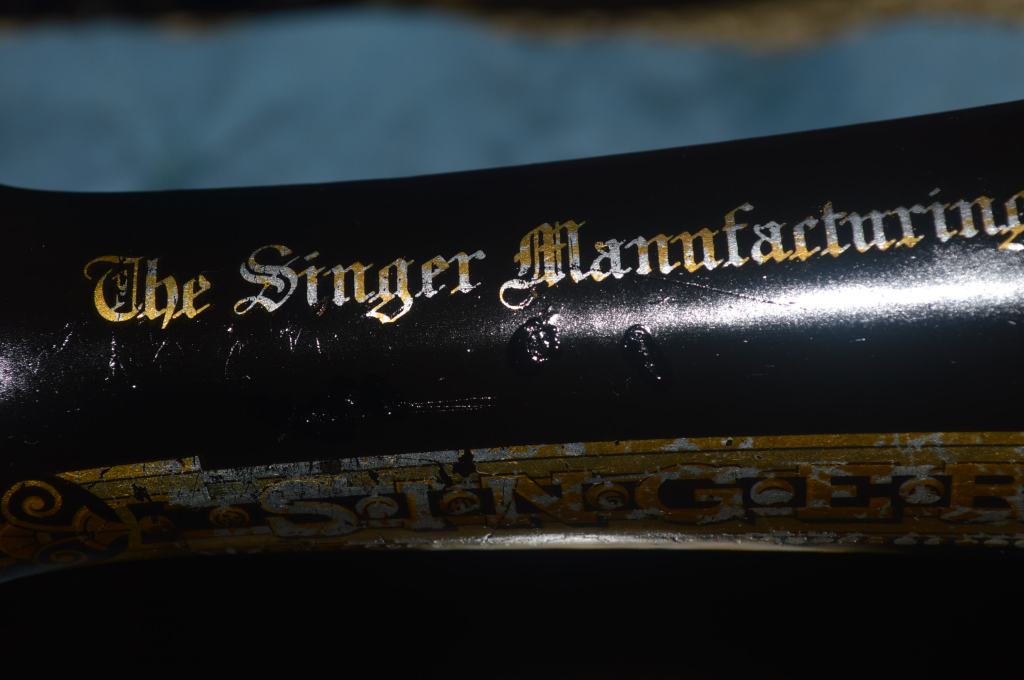

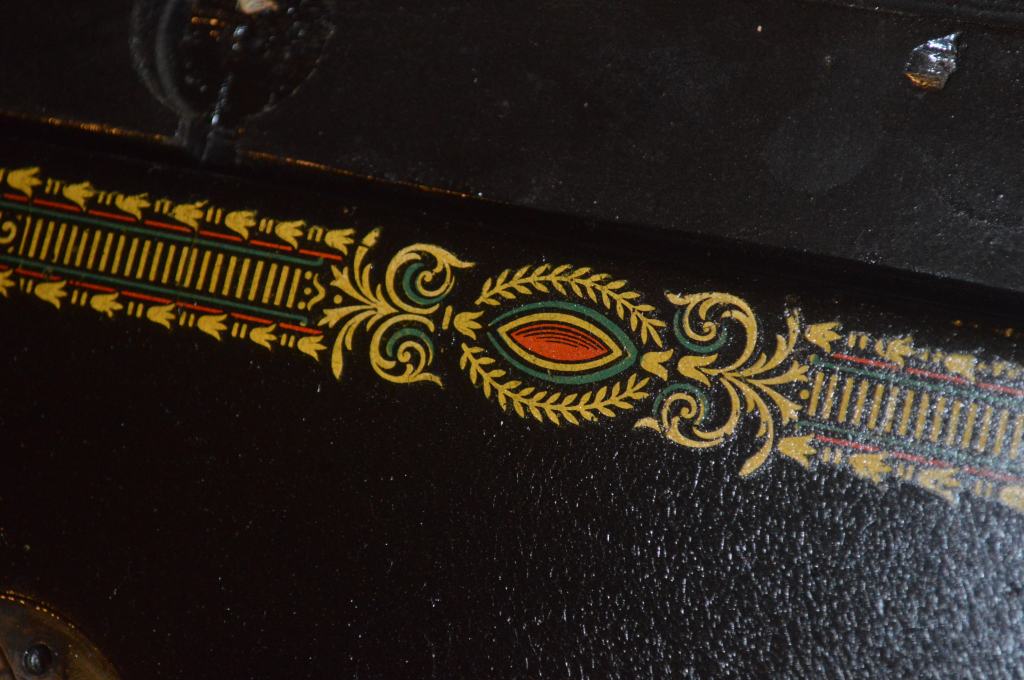

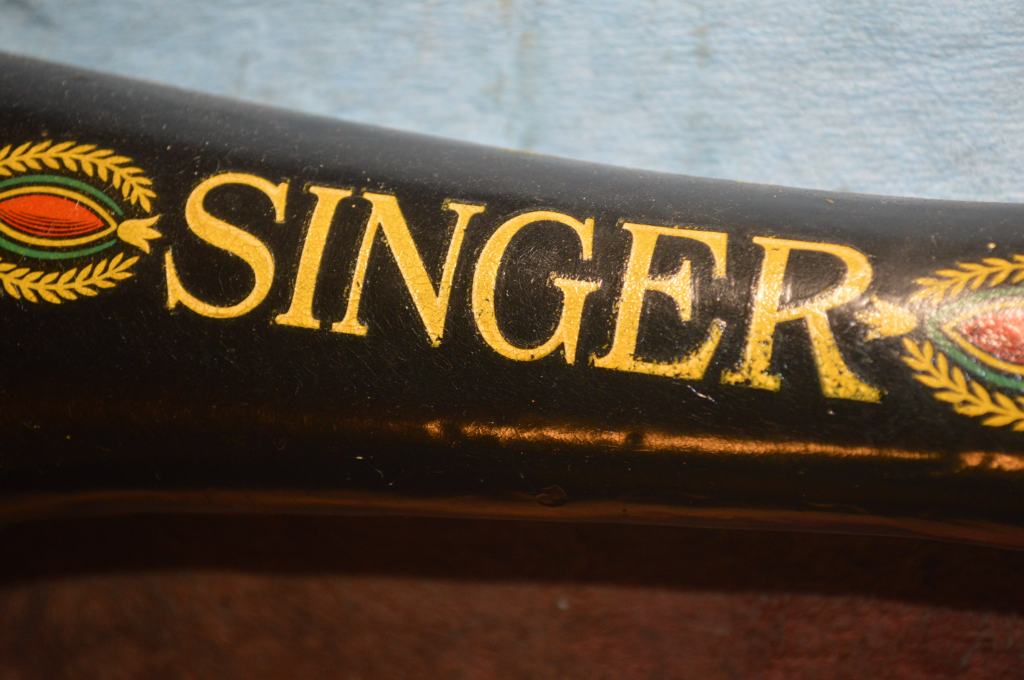

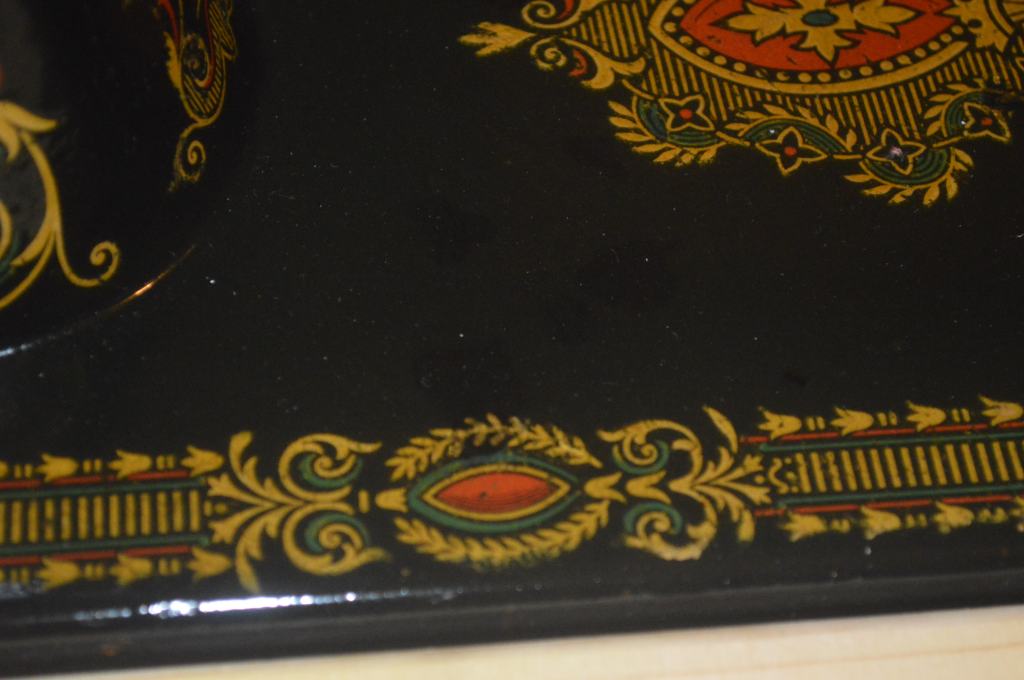

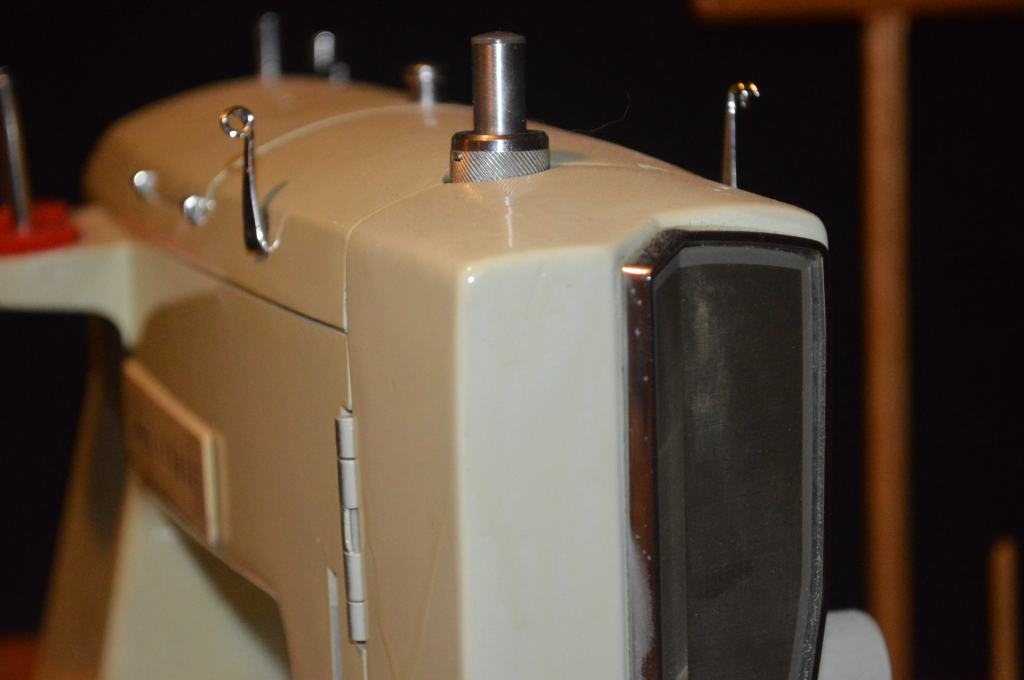

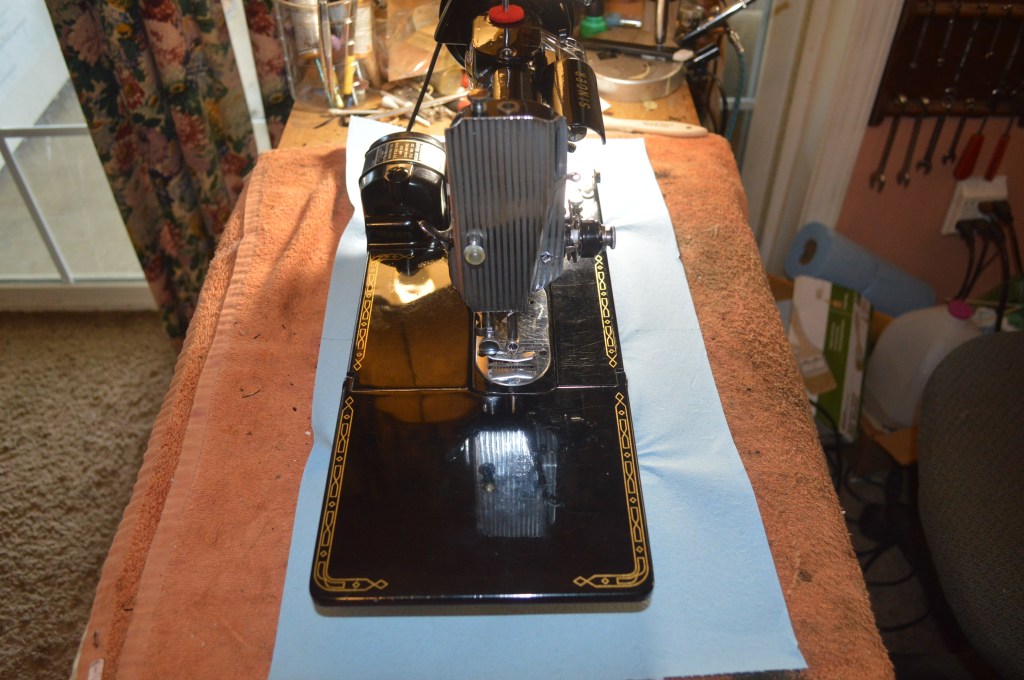

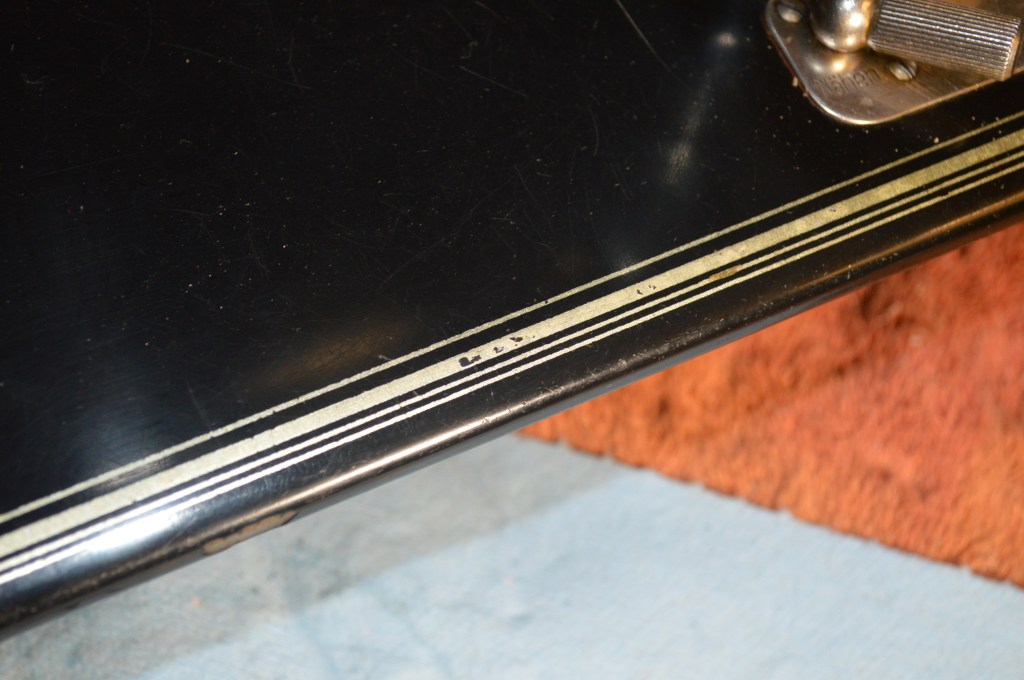

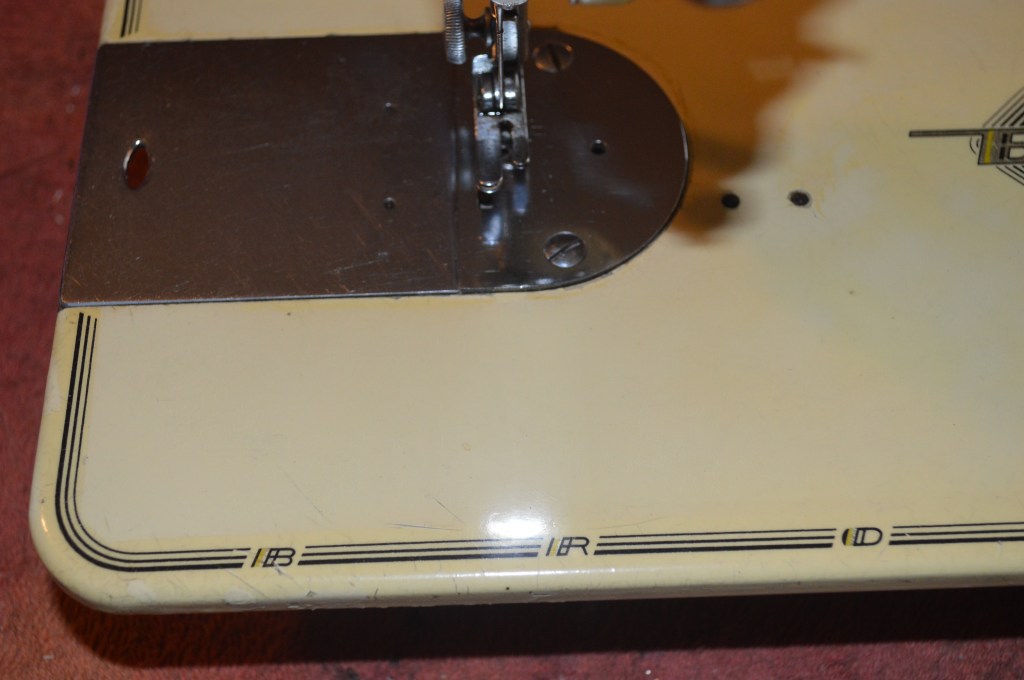

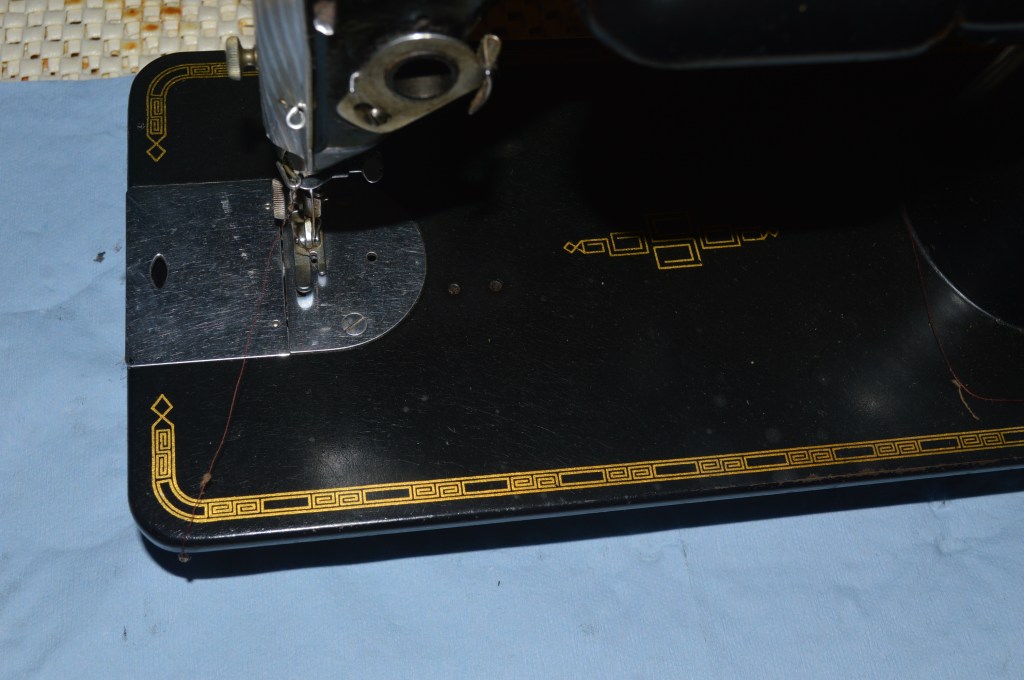

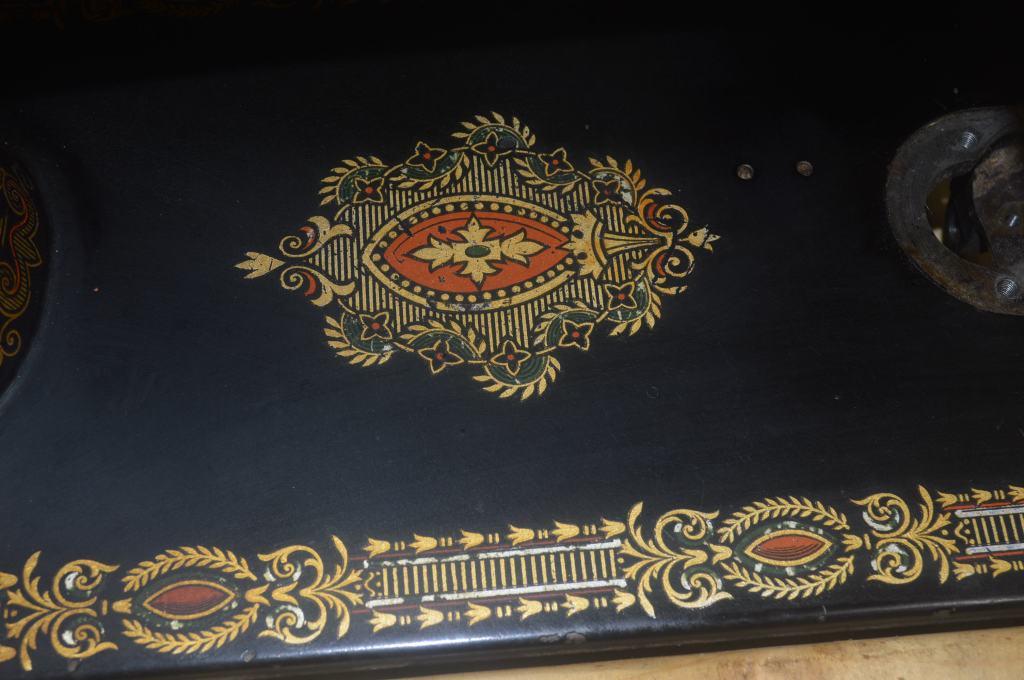

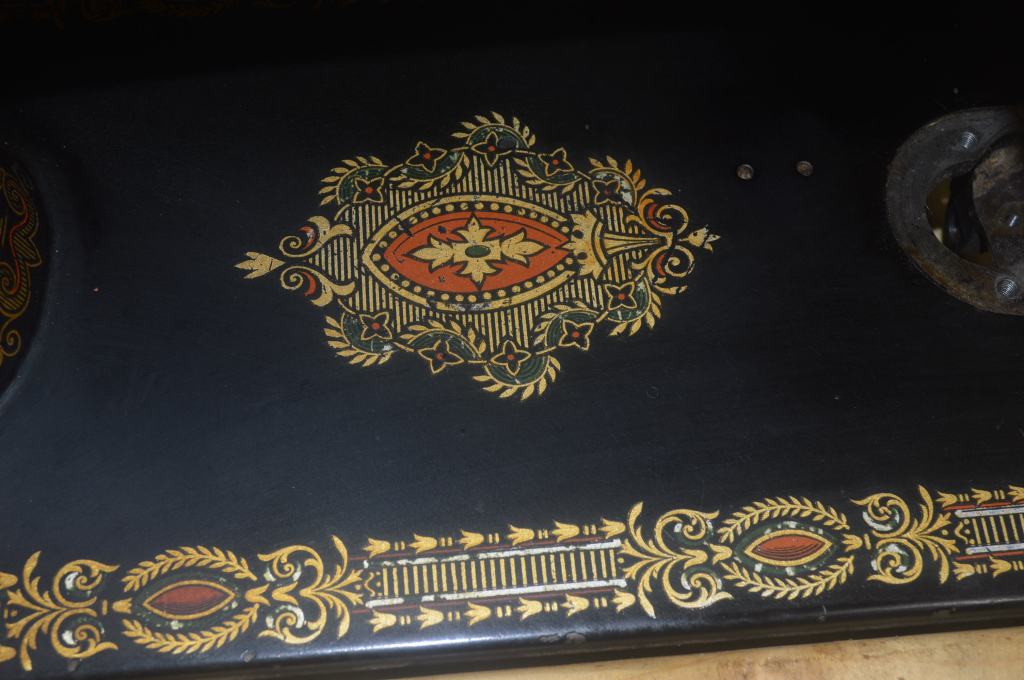

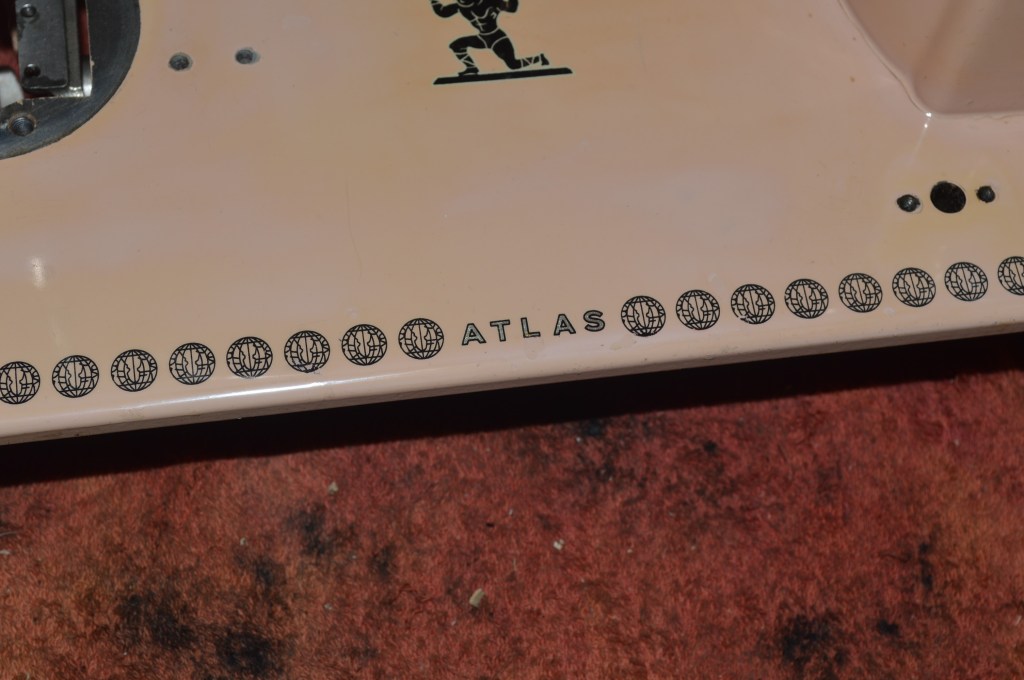

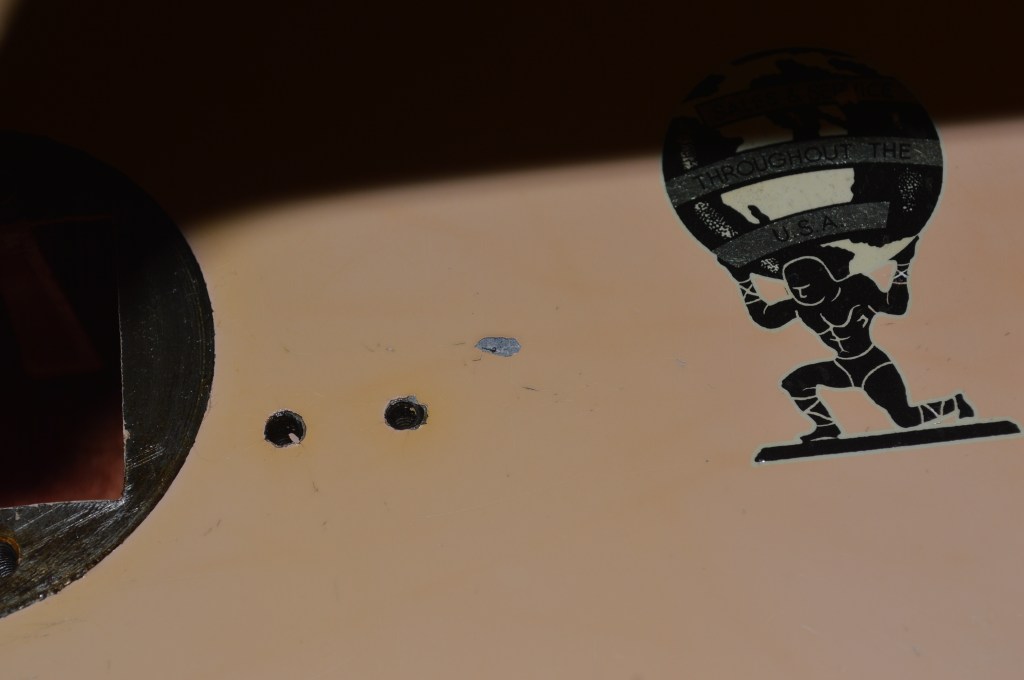

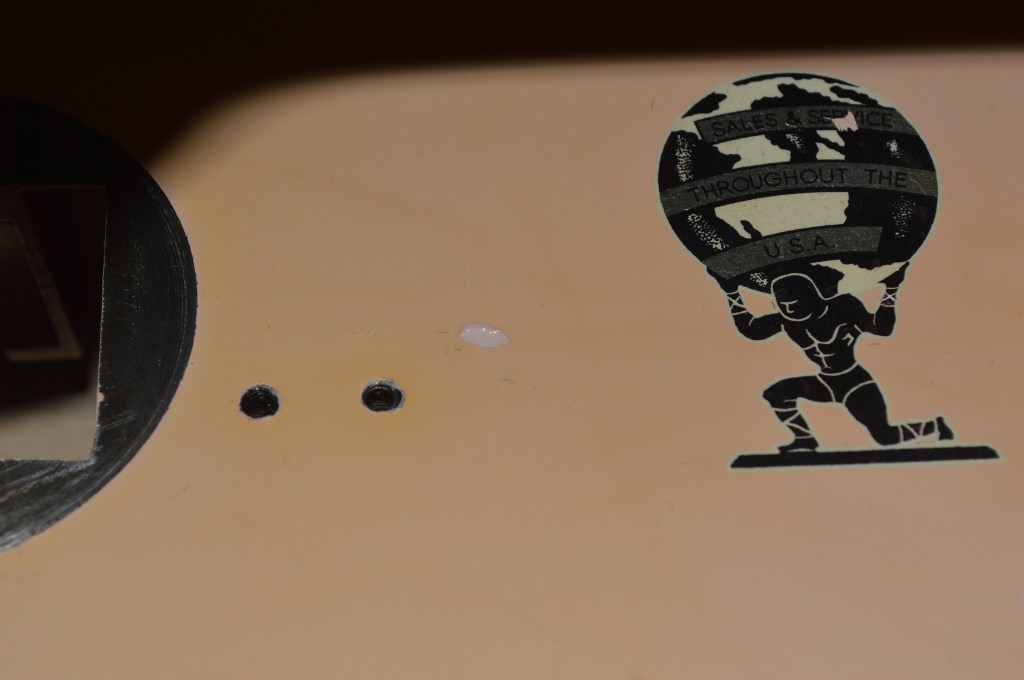

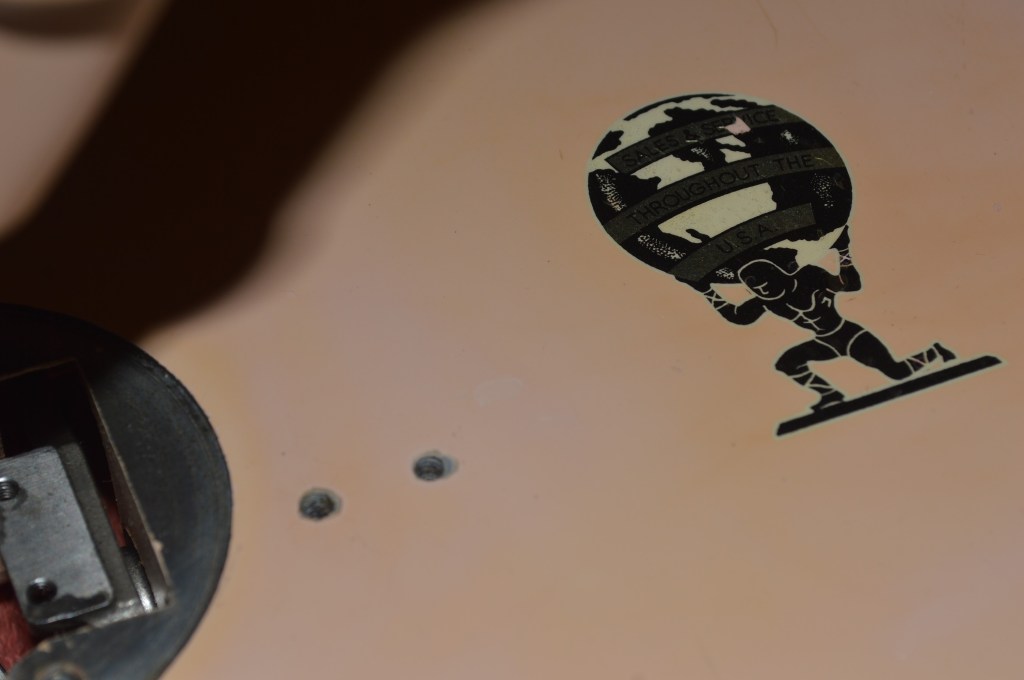

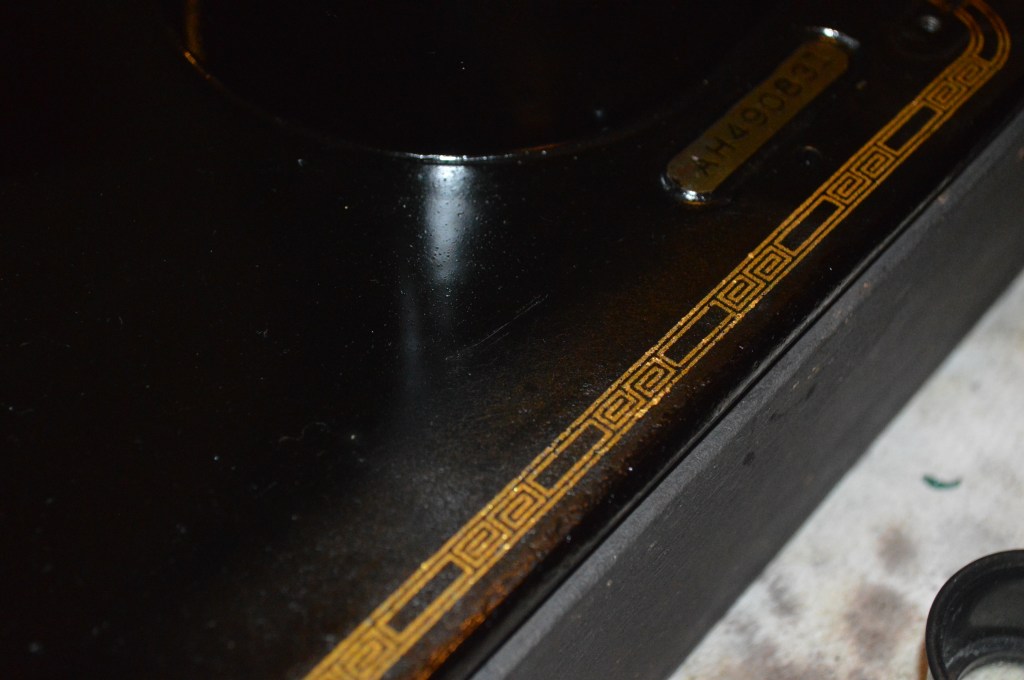

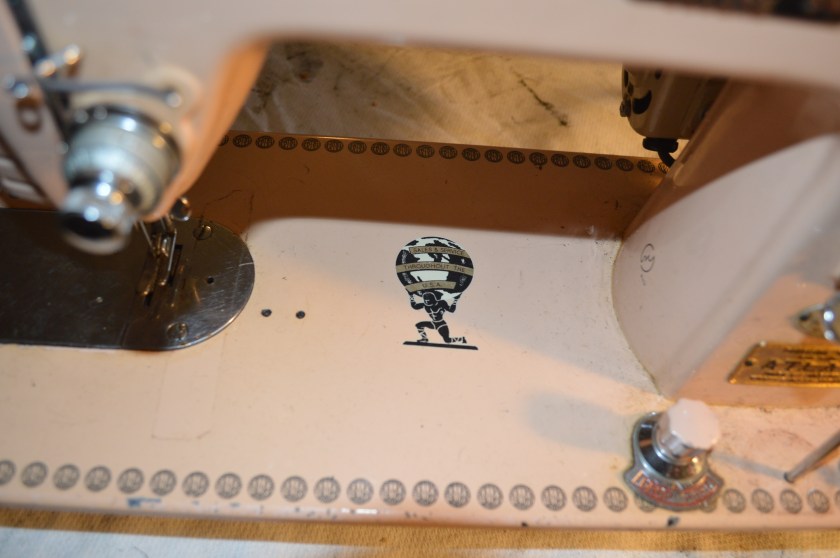

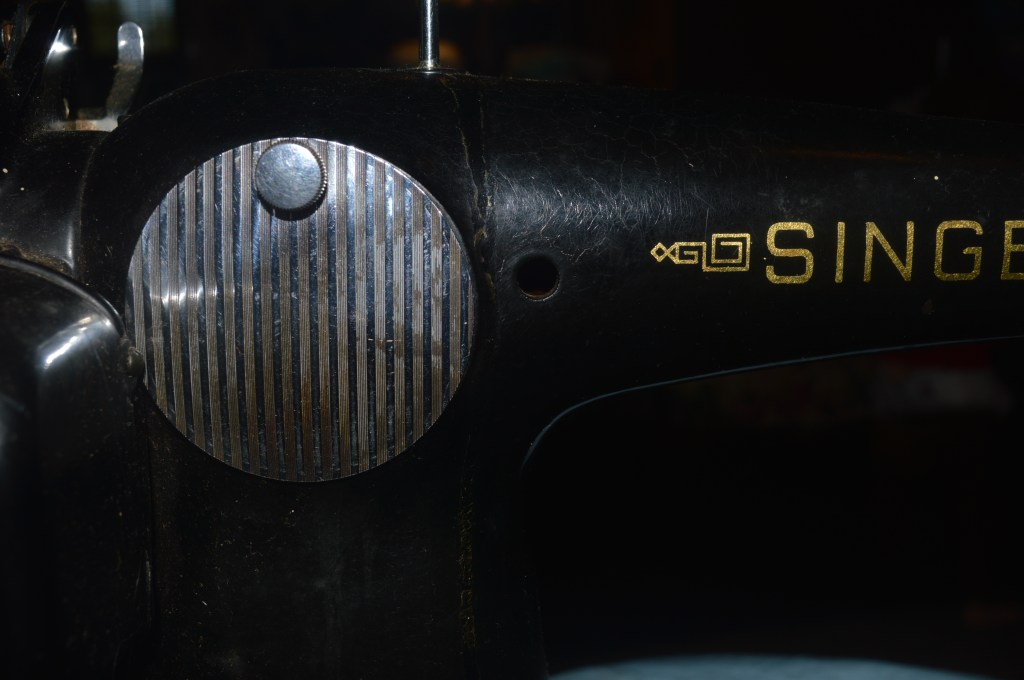

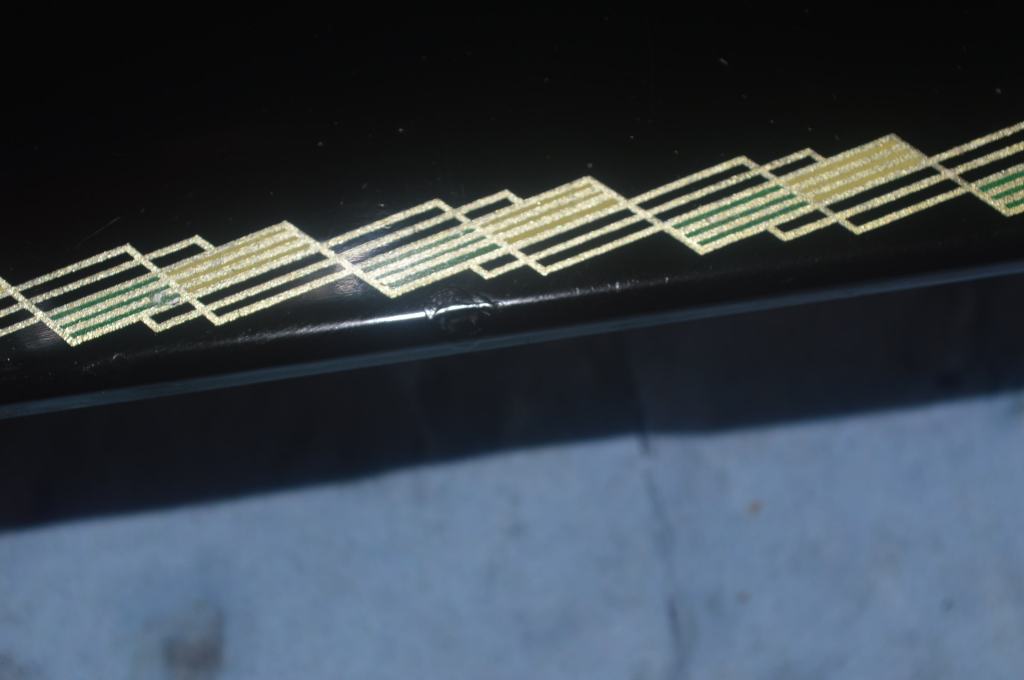

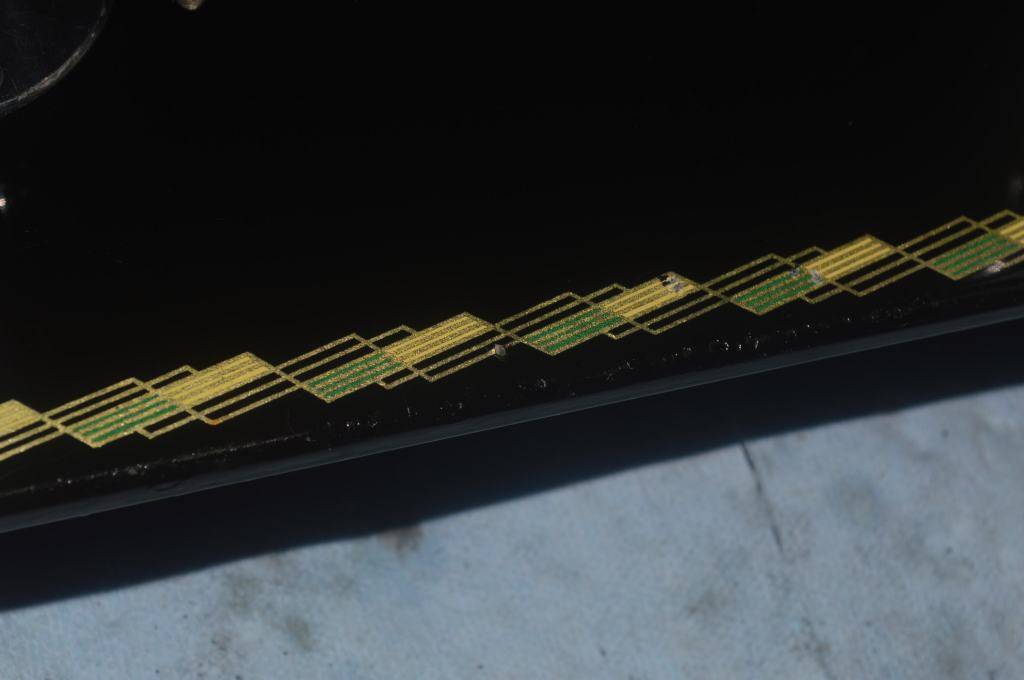

All in all, the machine looks to be in great condition. The paint (except where it was damaged) is in great condition, and the decals are in beautiful condition. The machine was a little stiff to turn by hand and the machine has it’s share of old oil varnish and packed lint. The biggest challenge is the paint repairs and I have high expectations for the restoration outcome.

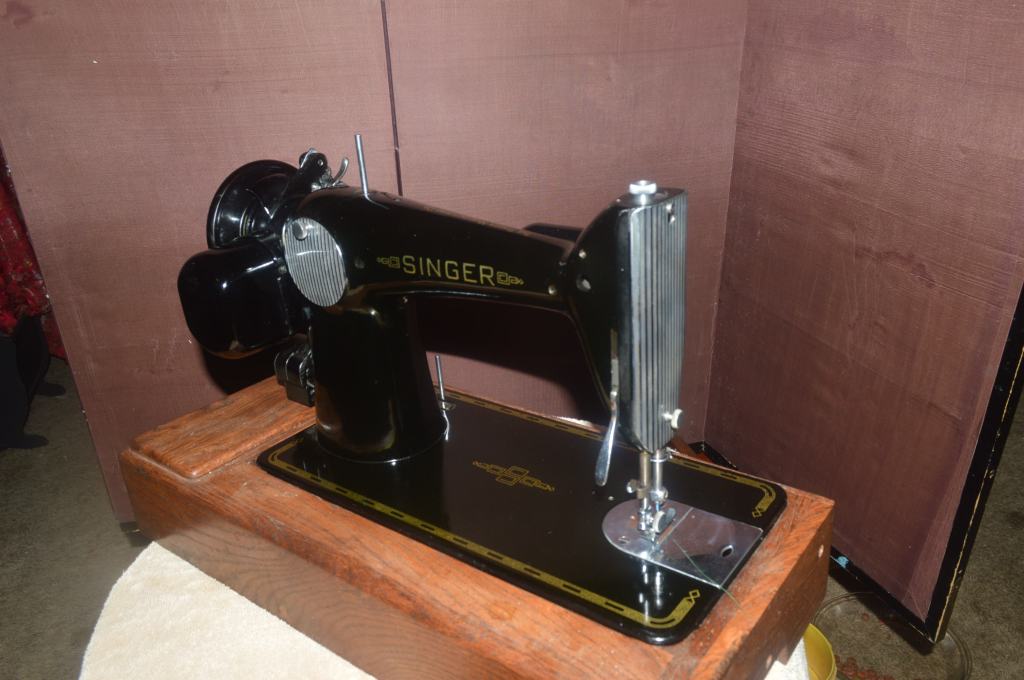

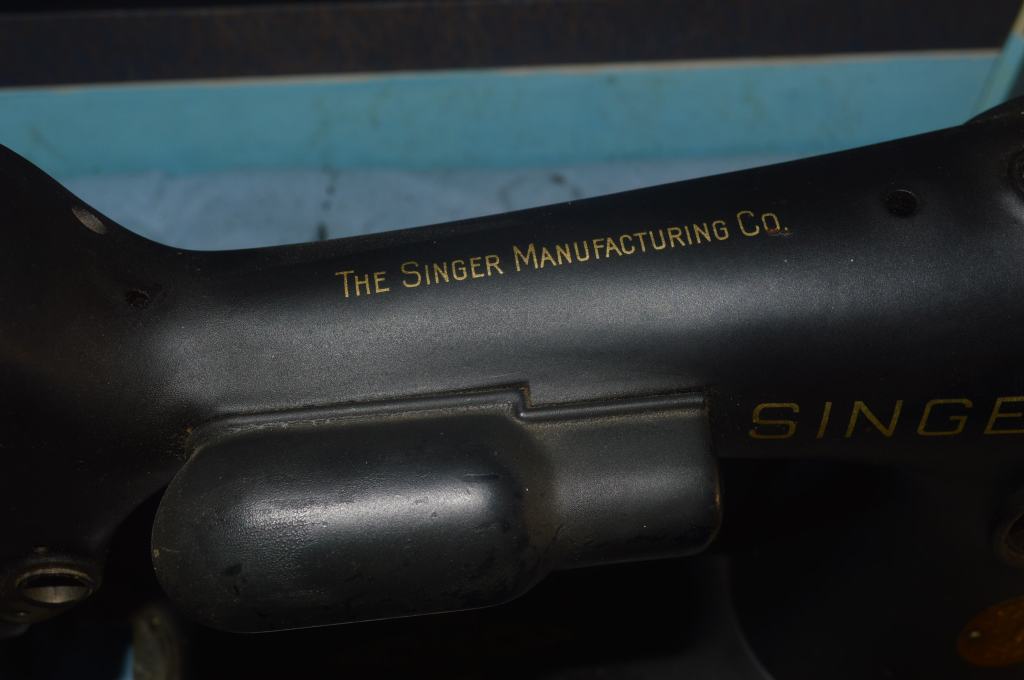

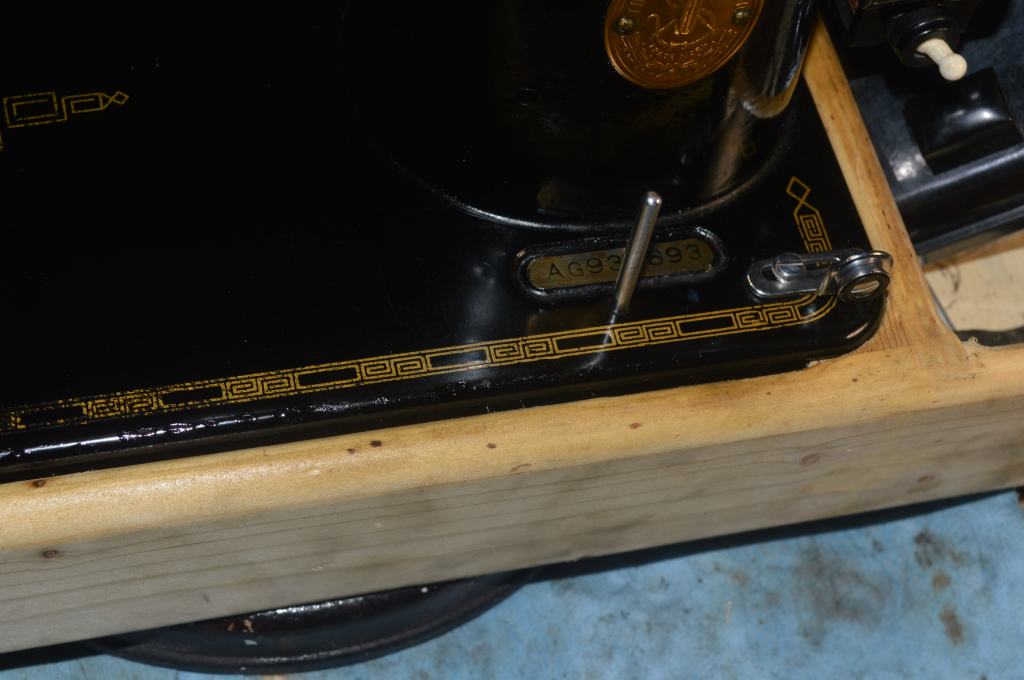

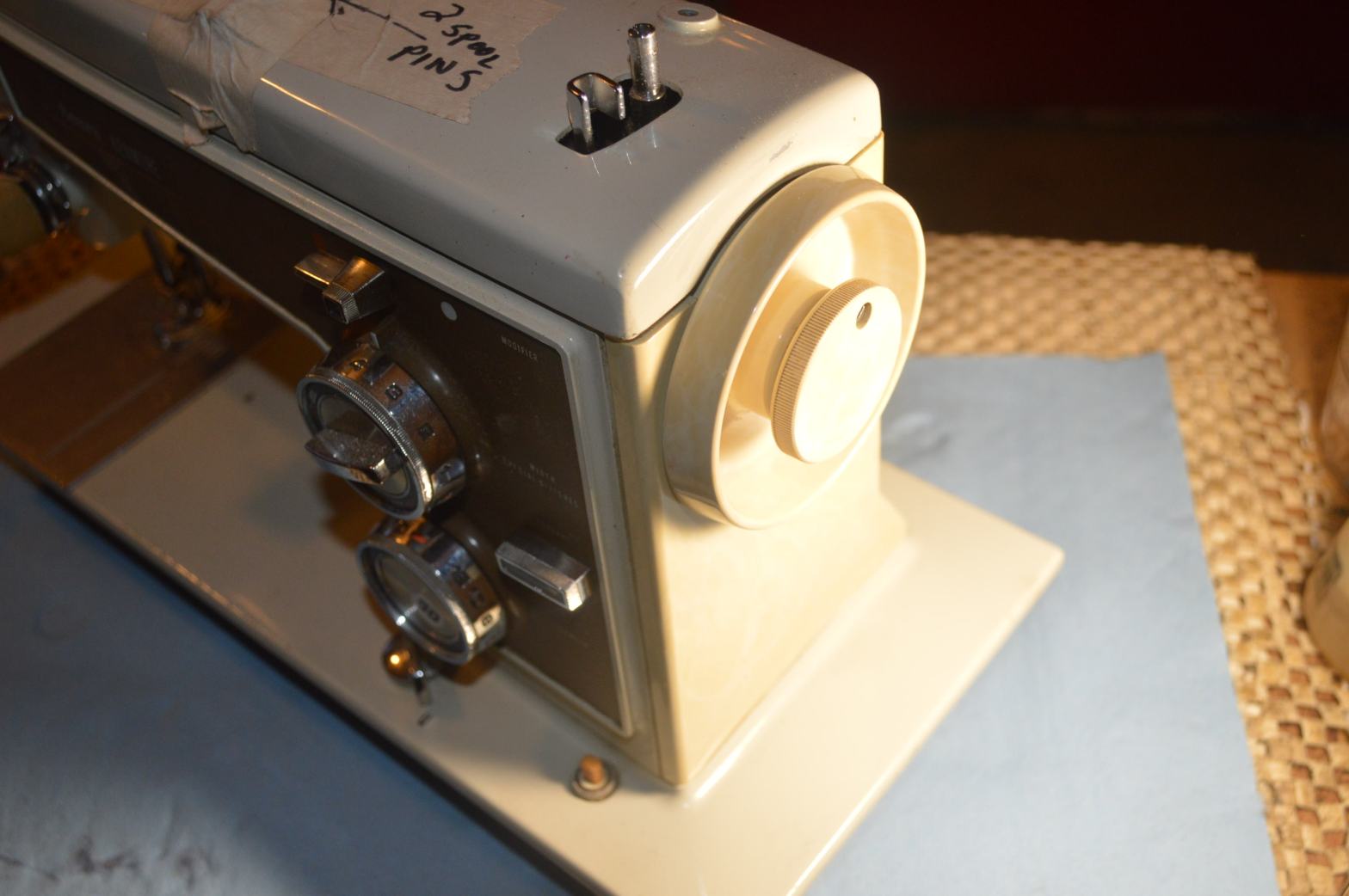

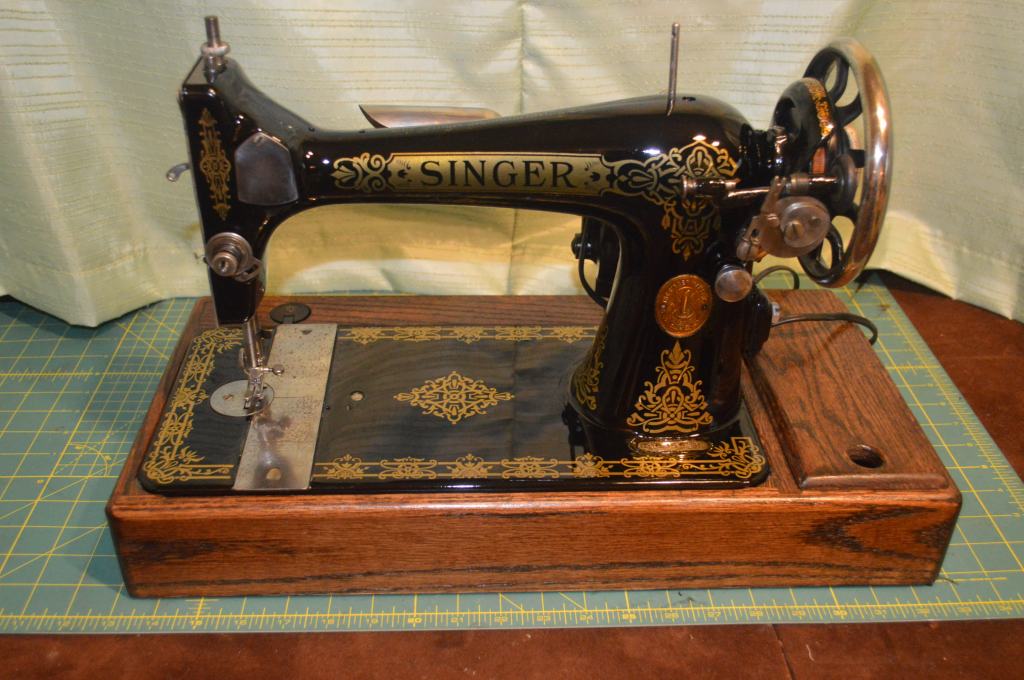

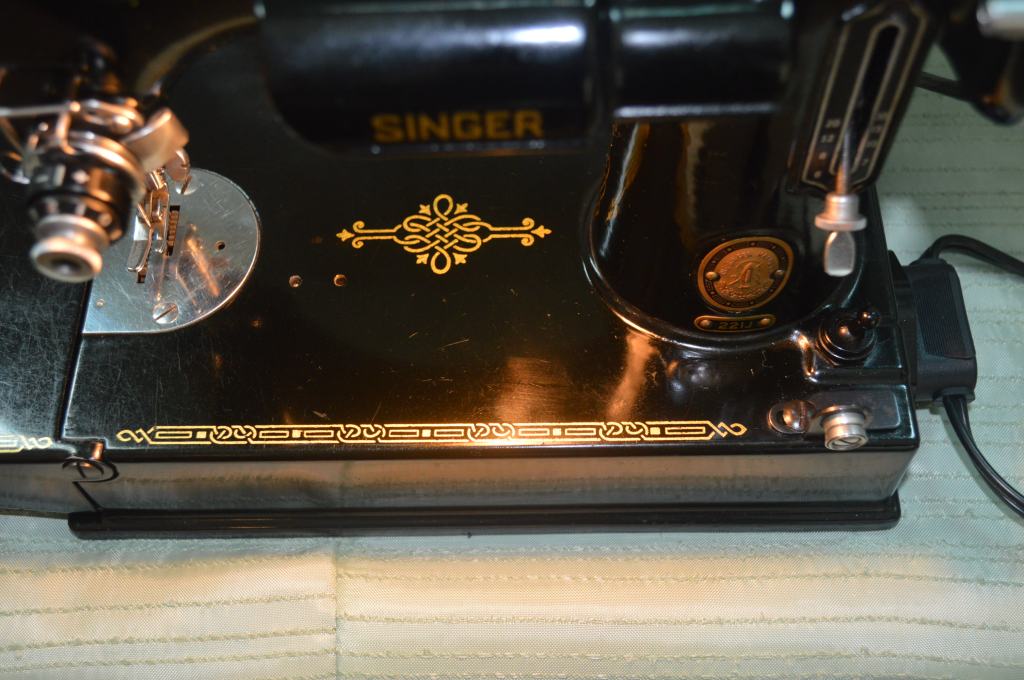

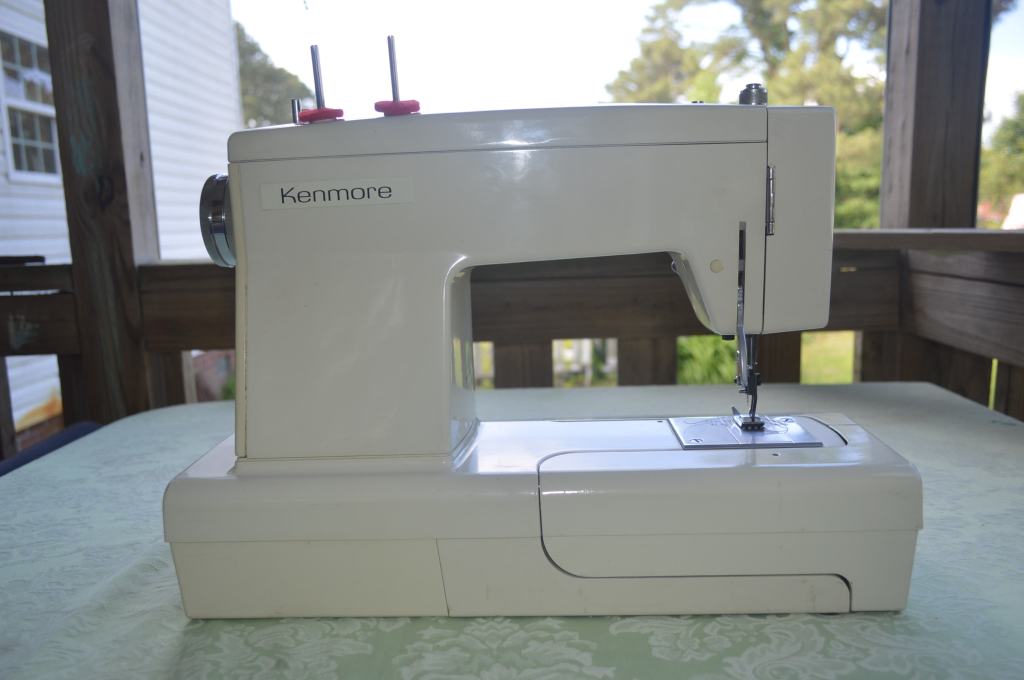

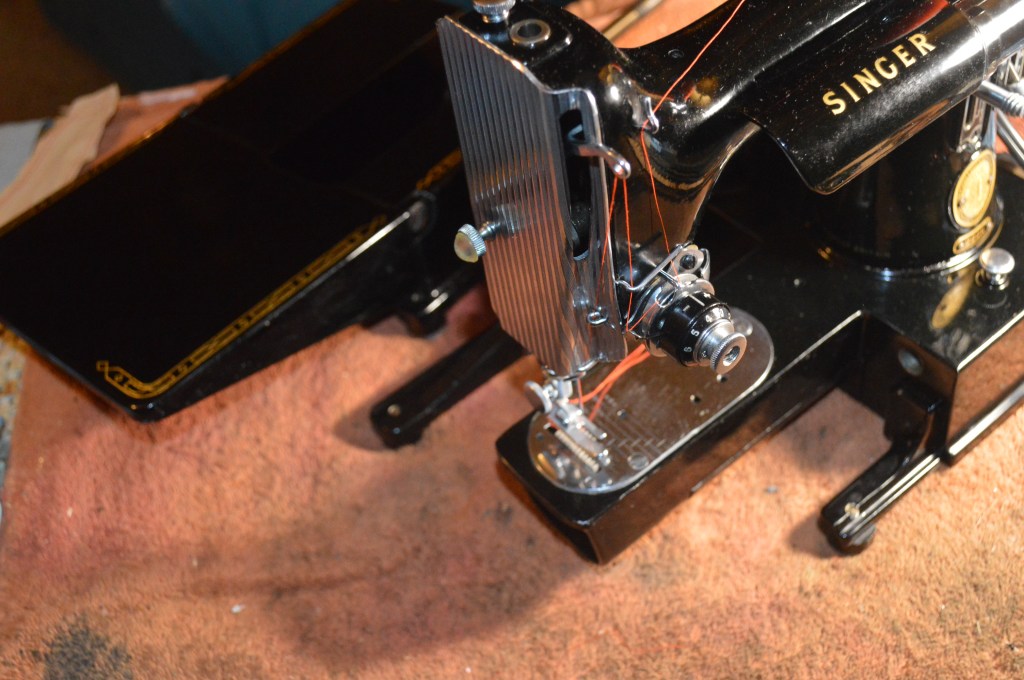

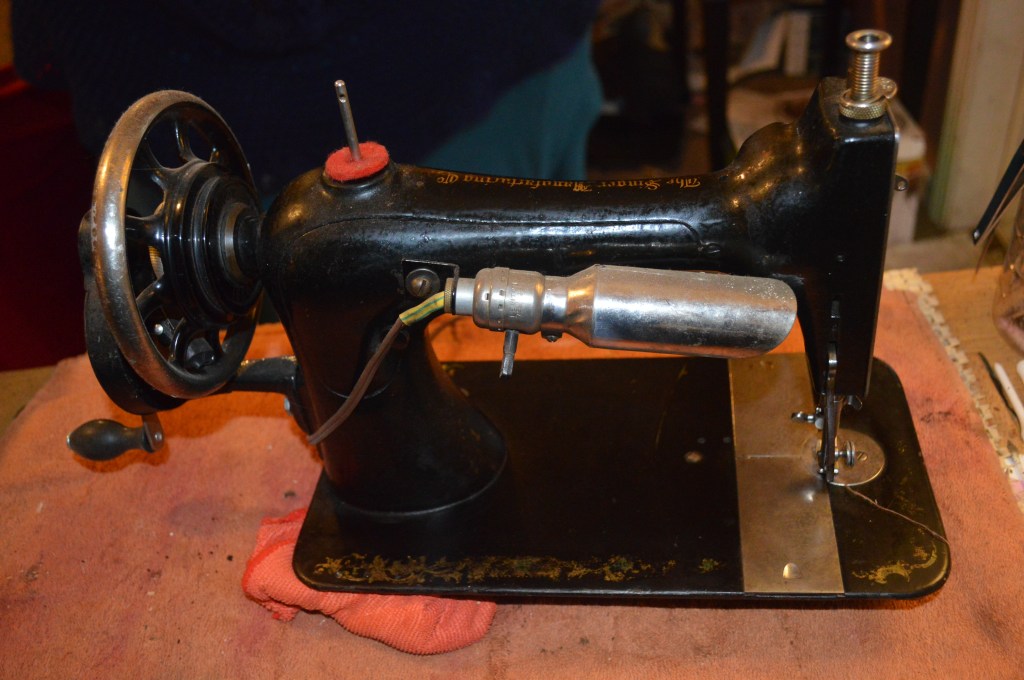

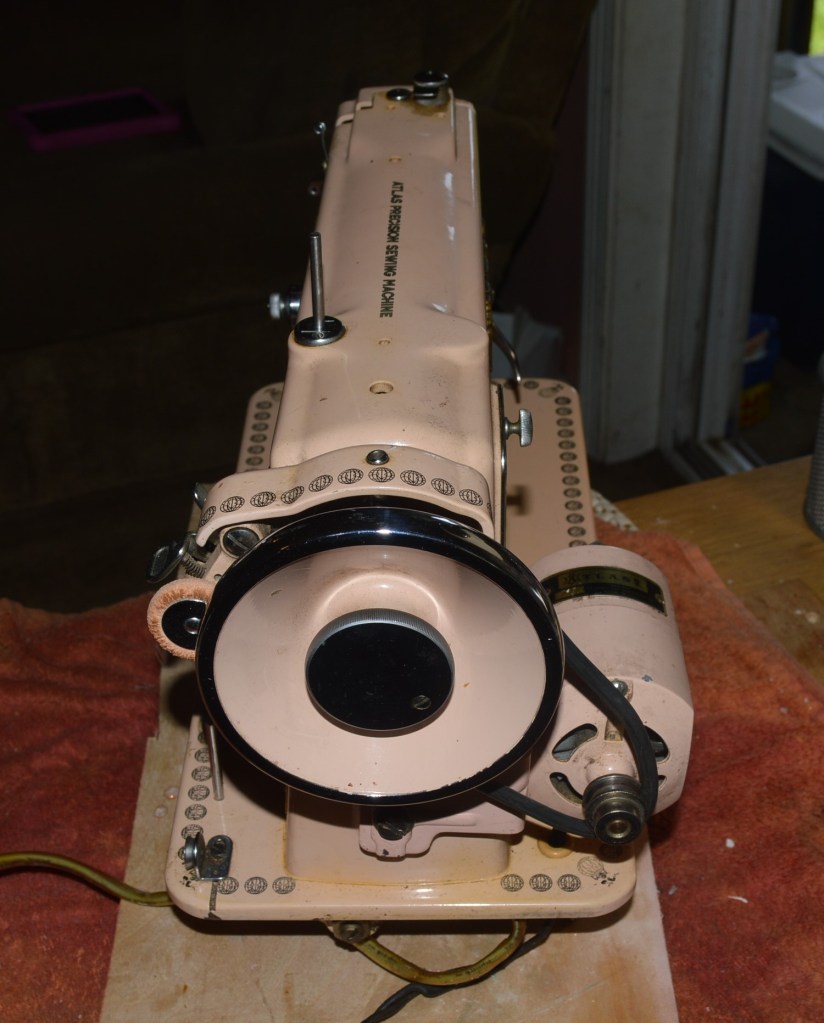

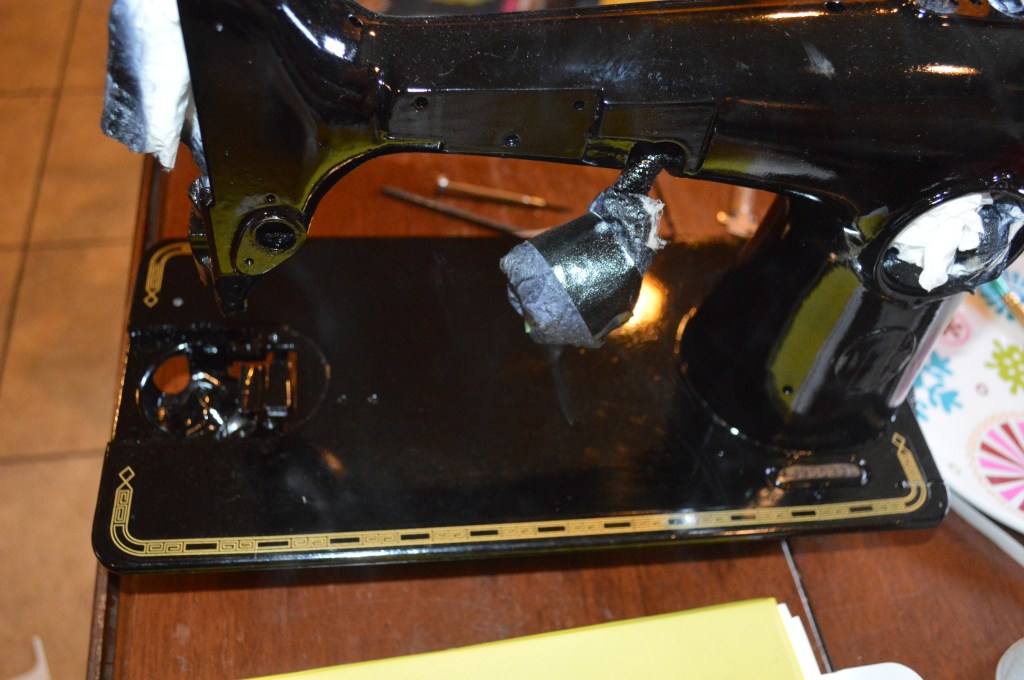

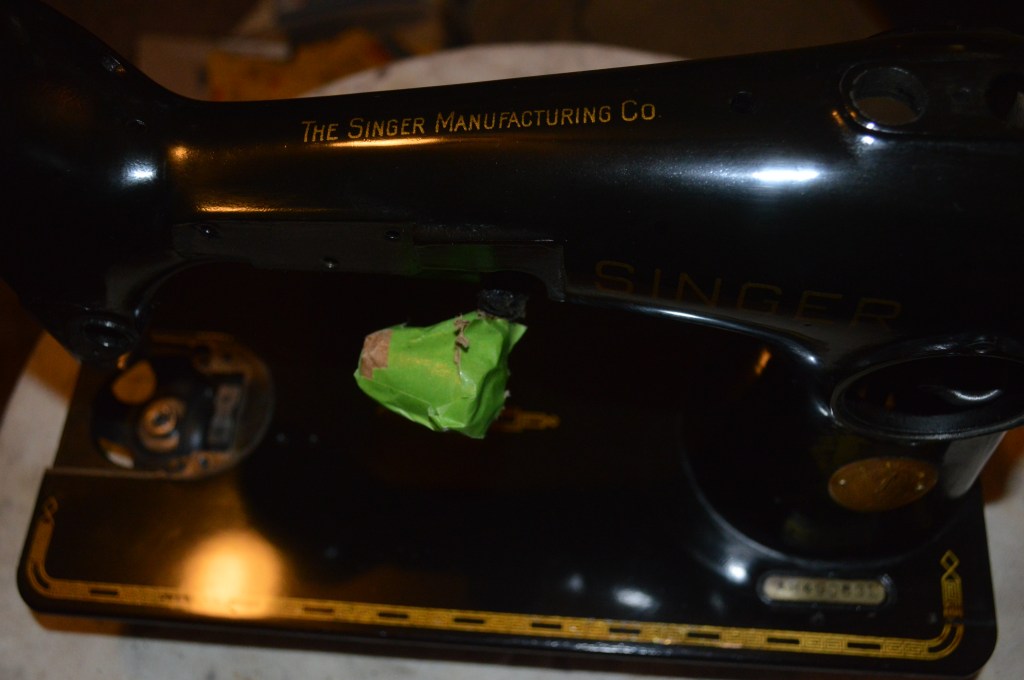

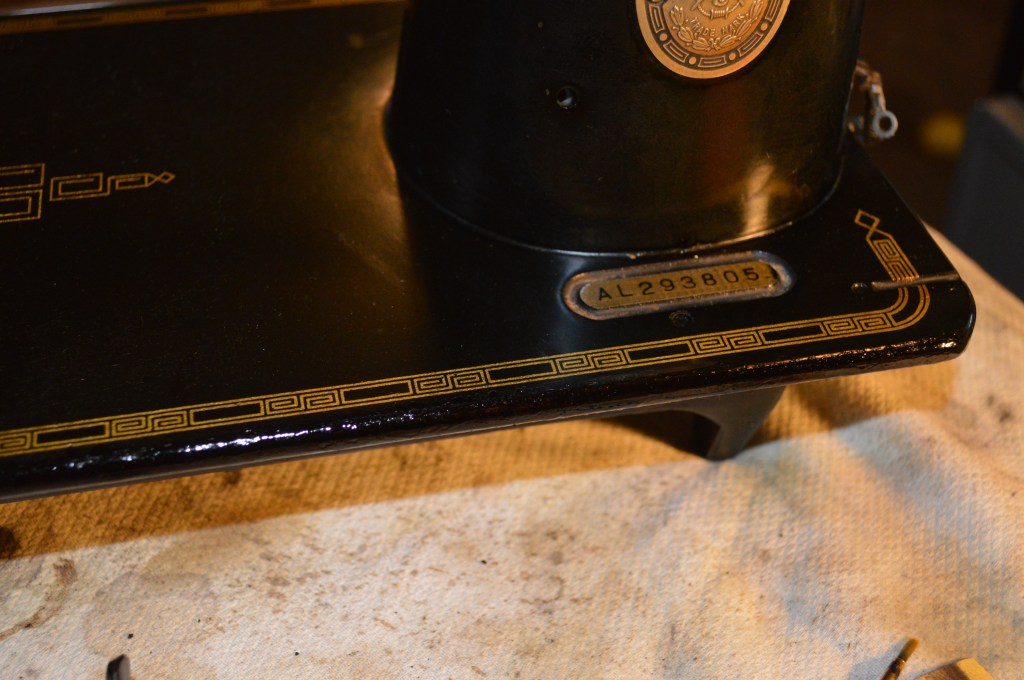

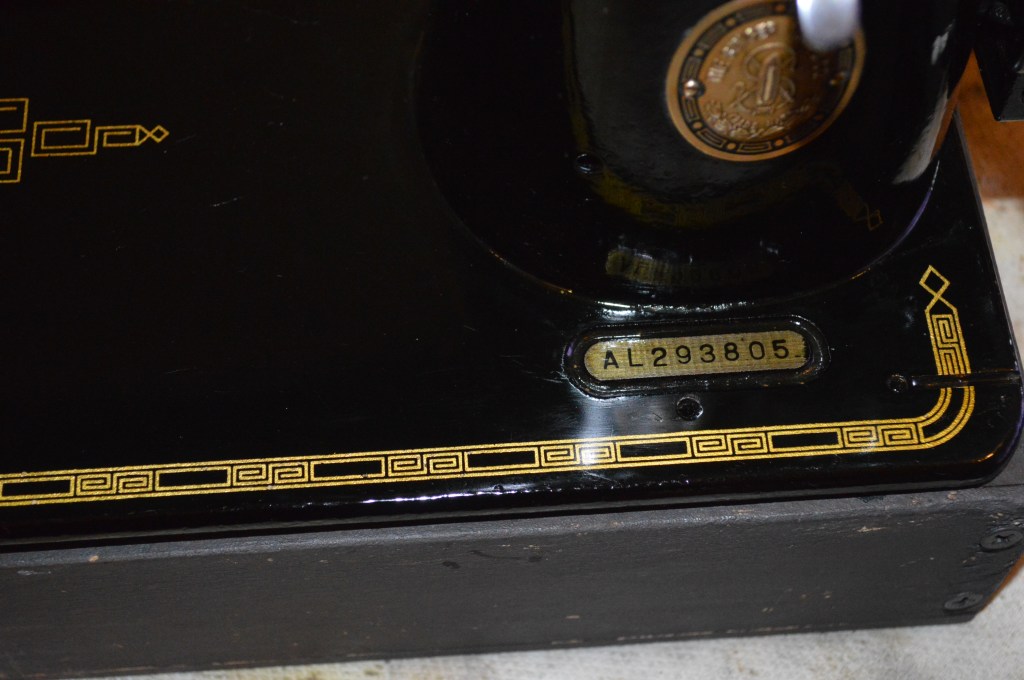

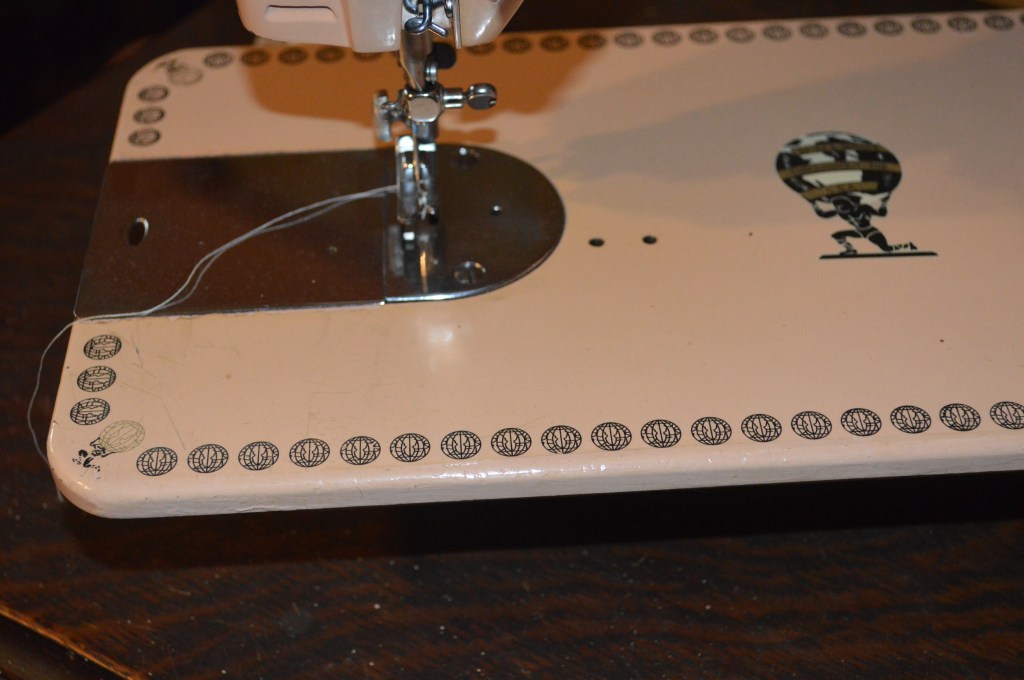

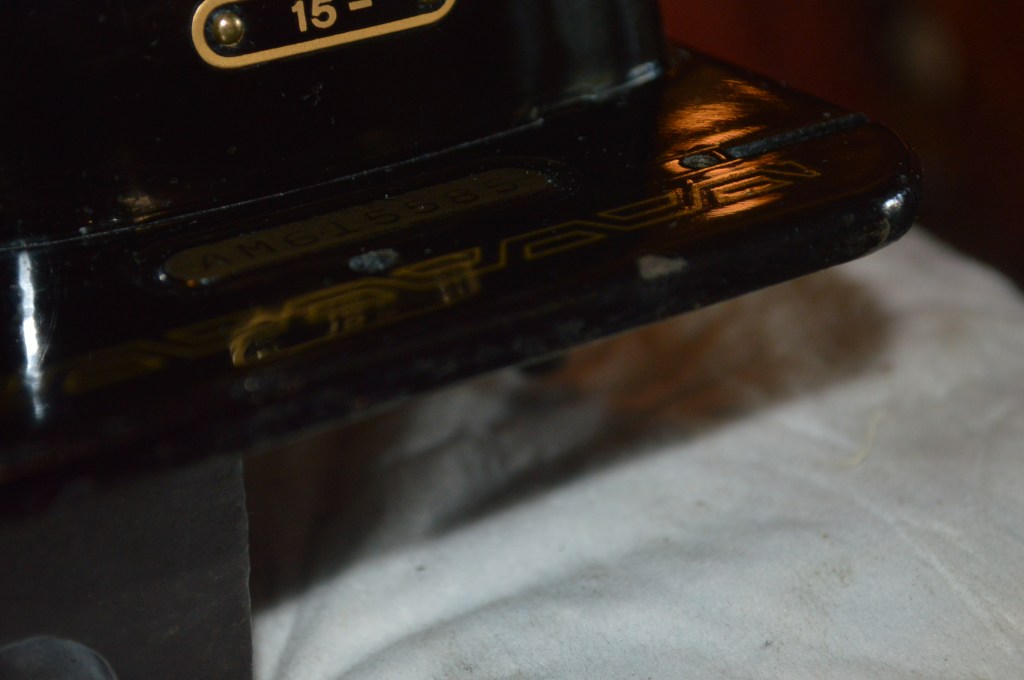

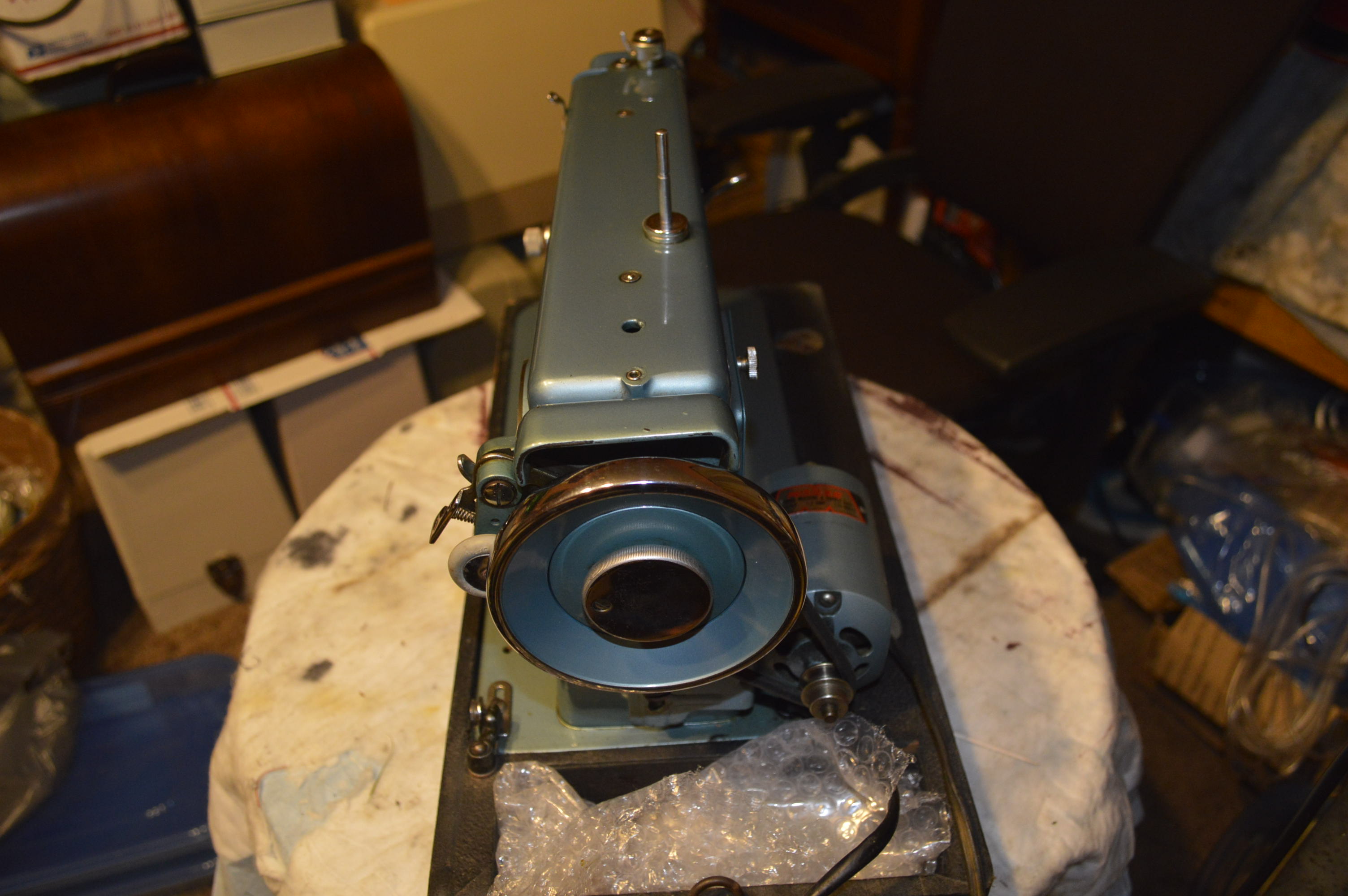

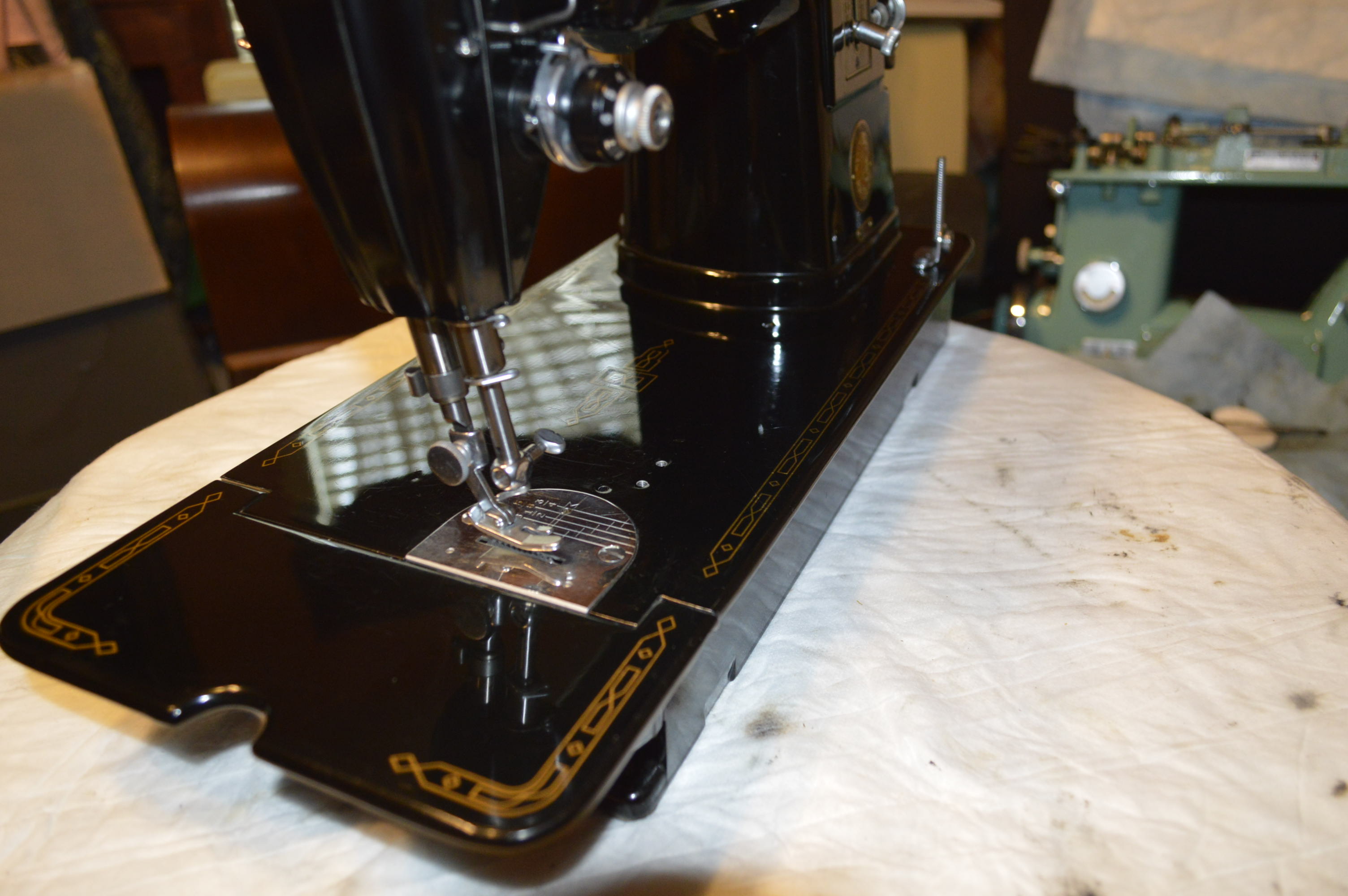

Here is the machine before the start of the restoration:

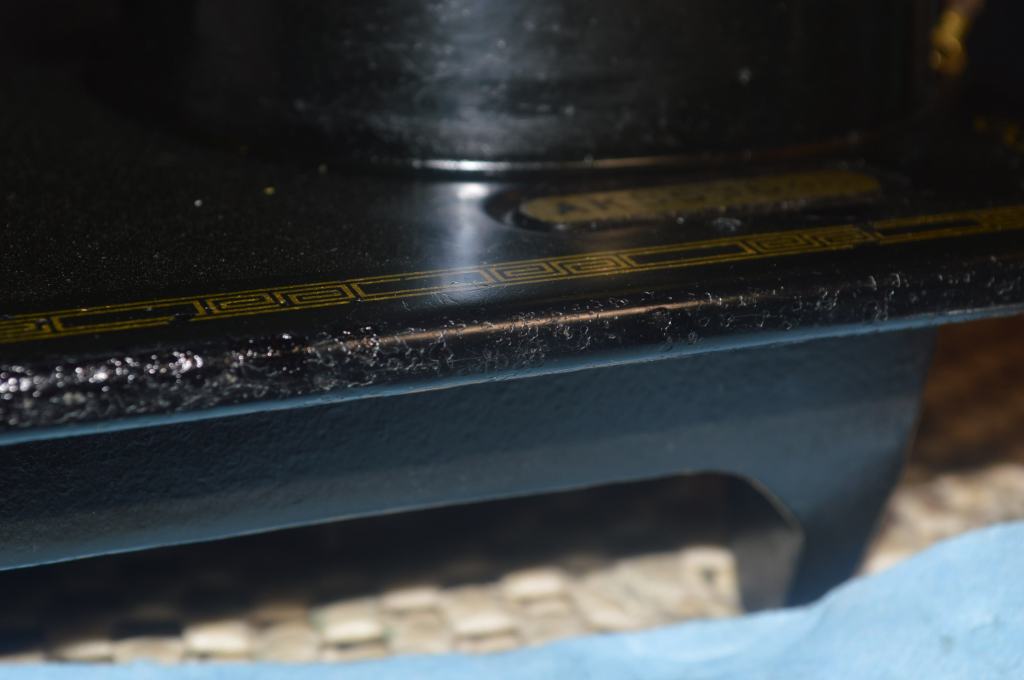

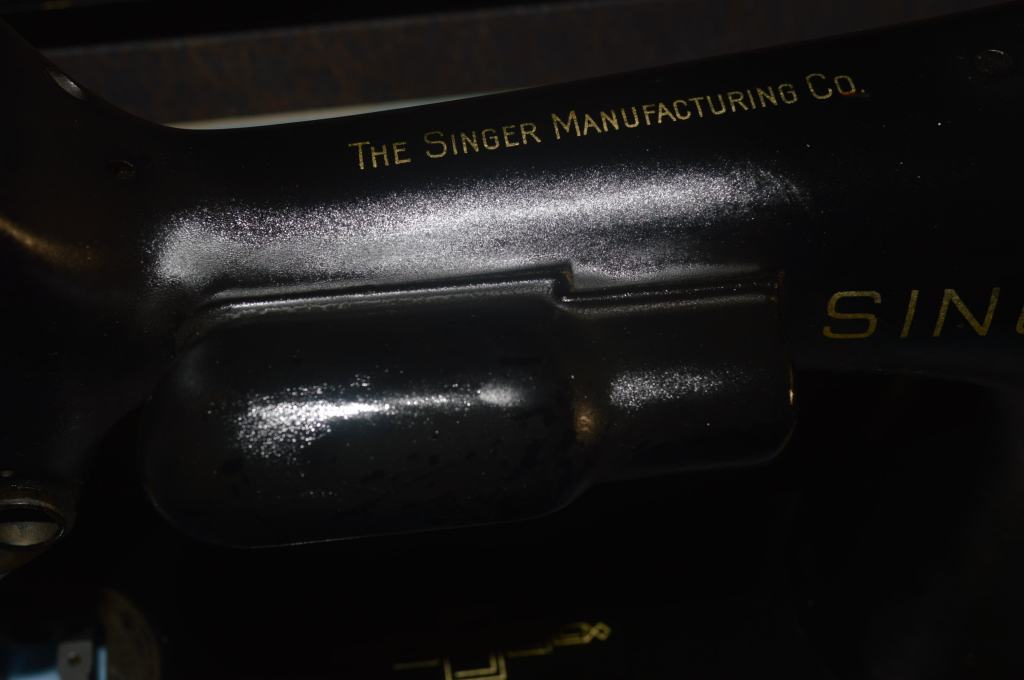

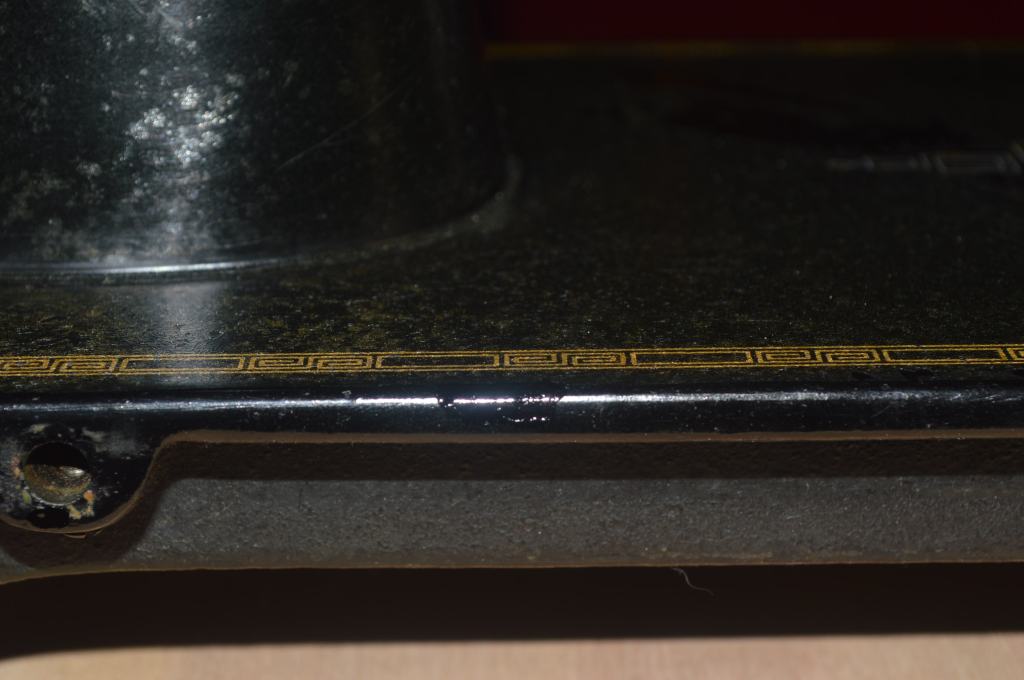

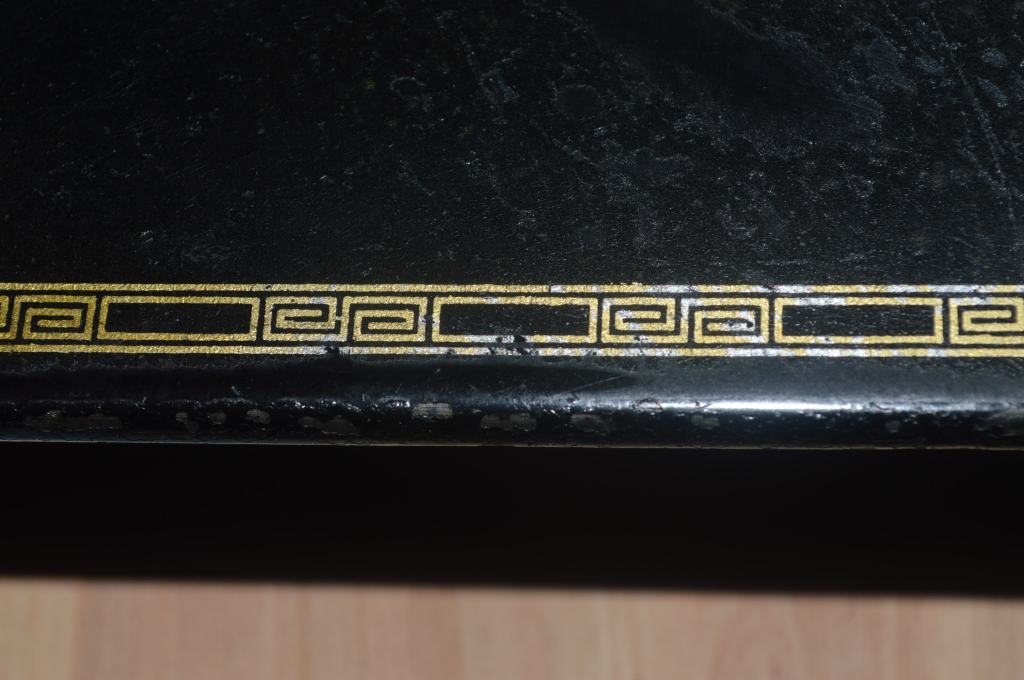

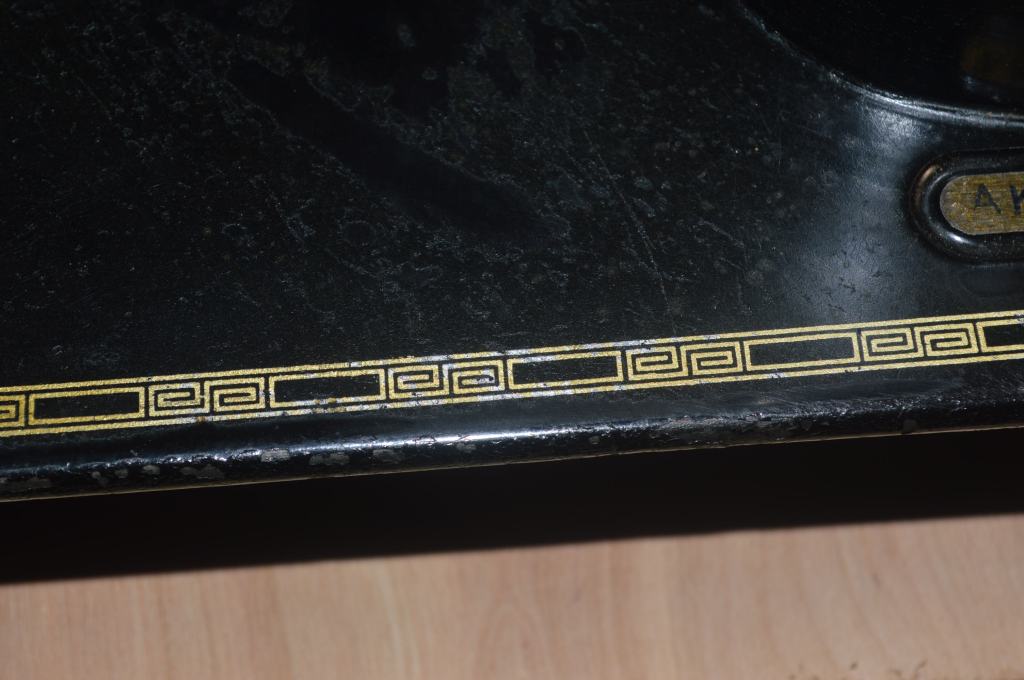

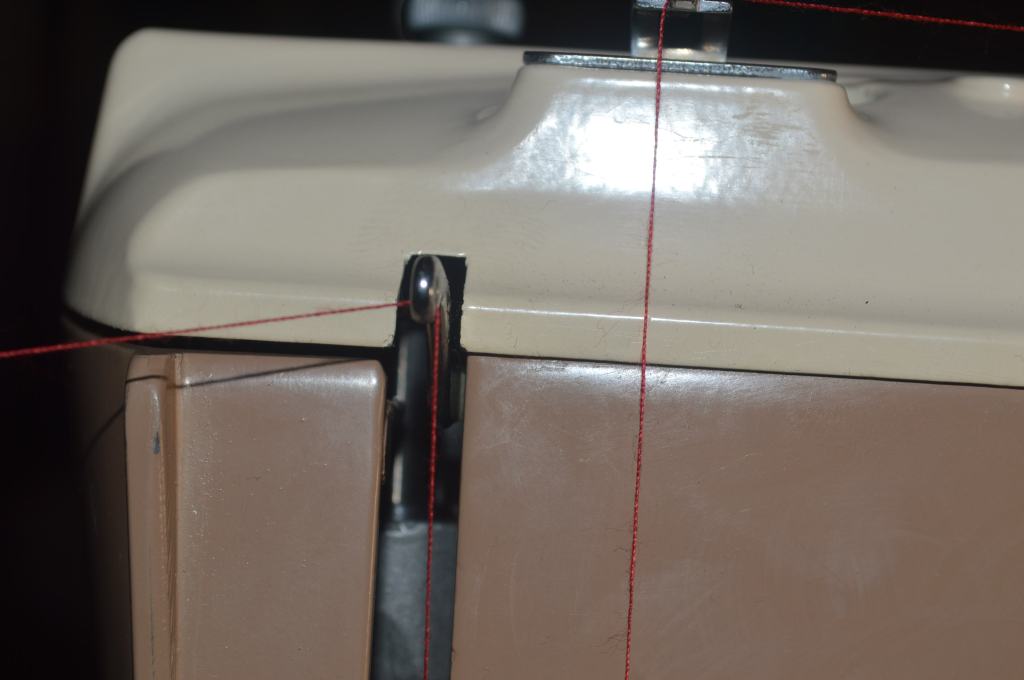

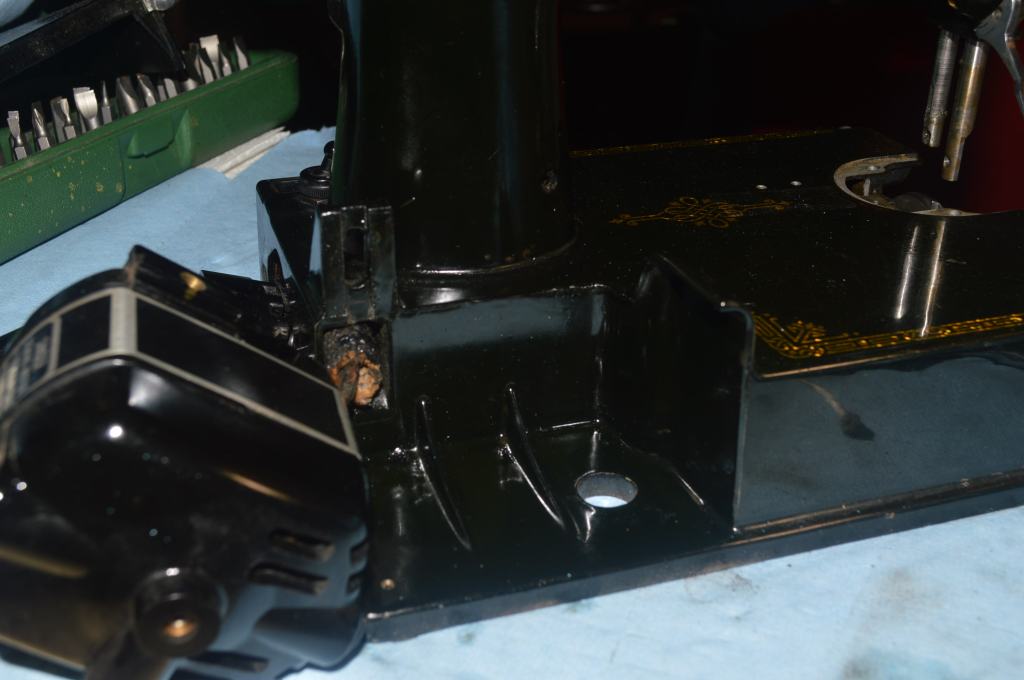

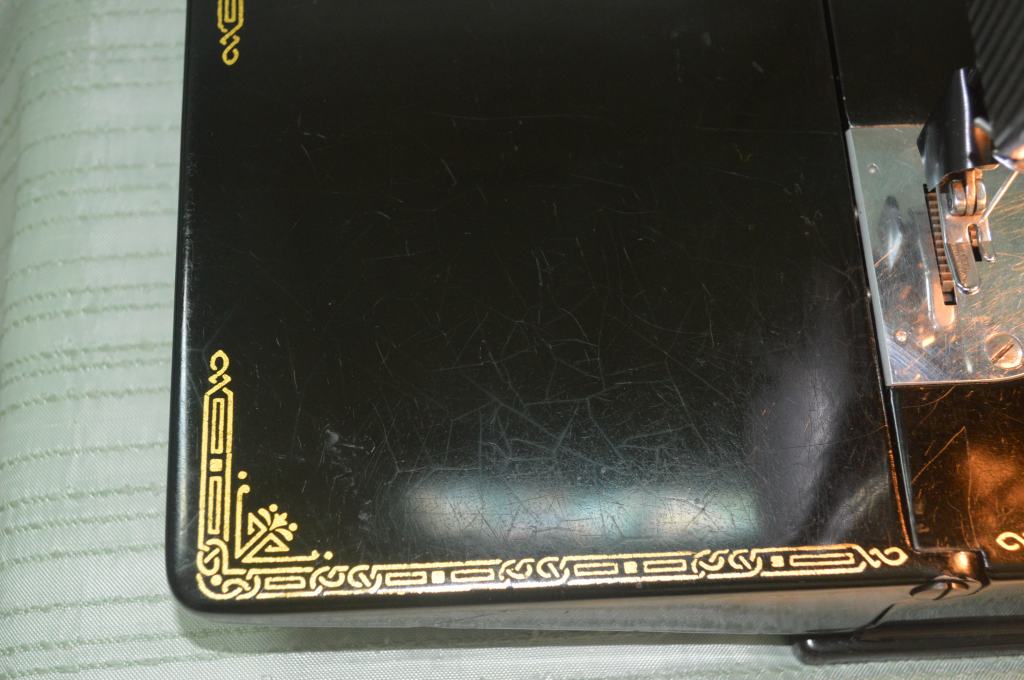

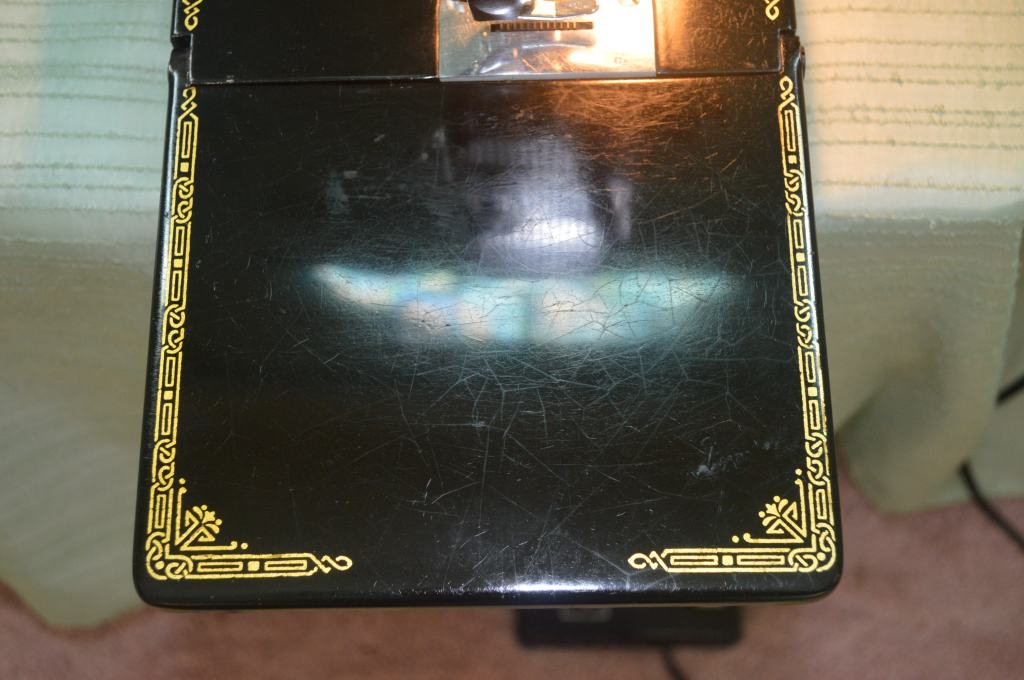

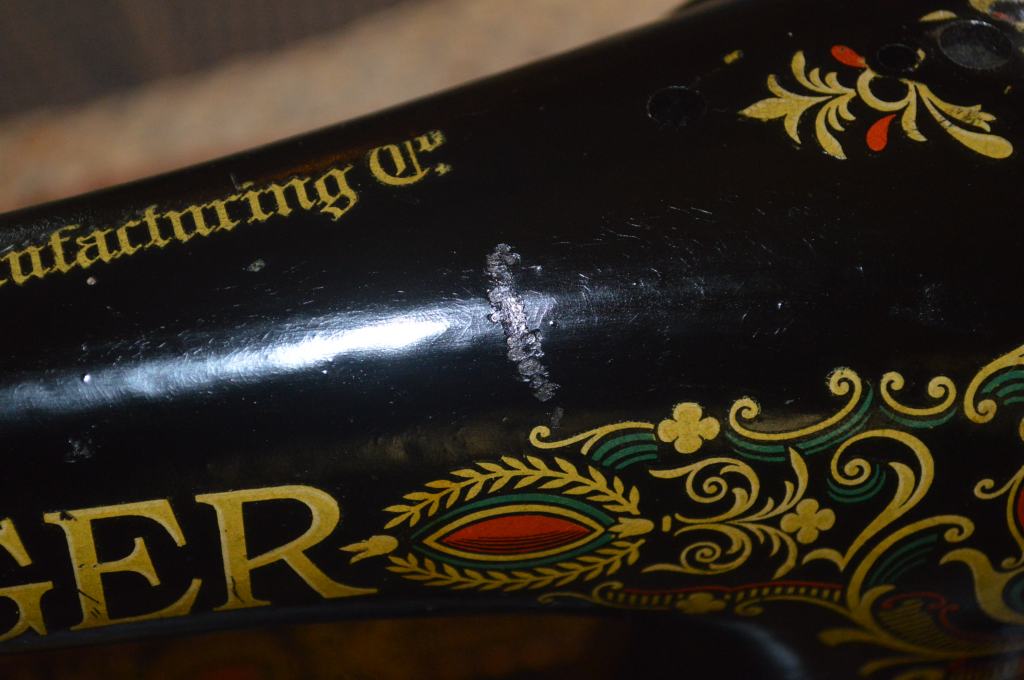

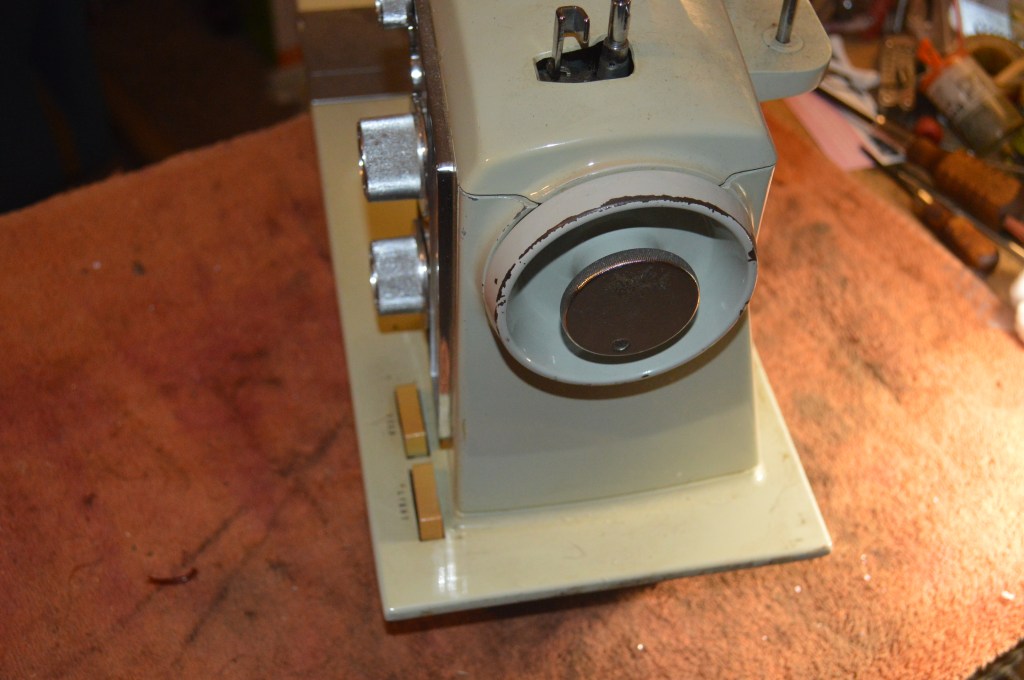

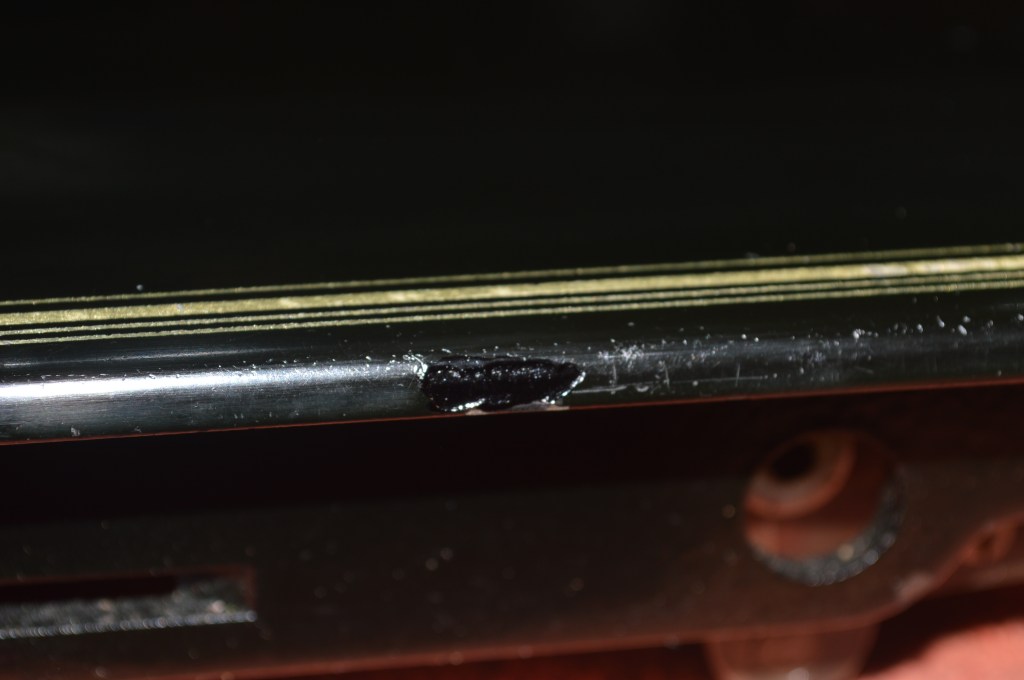

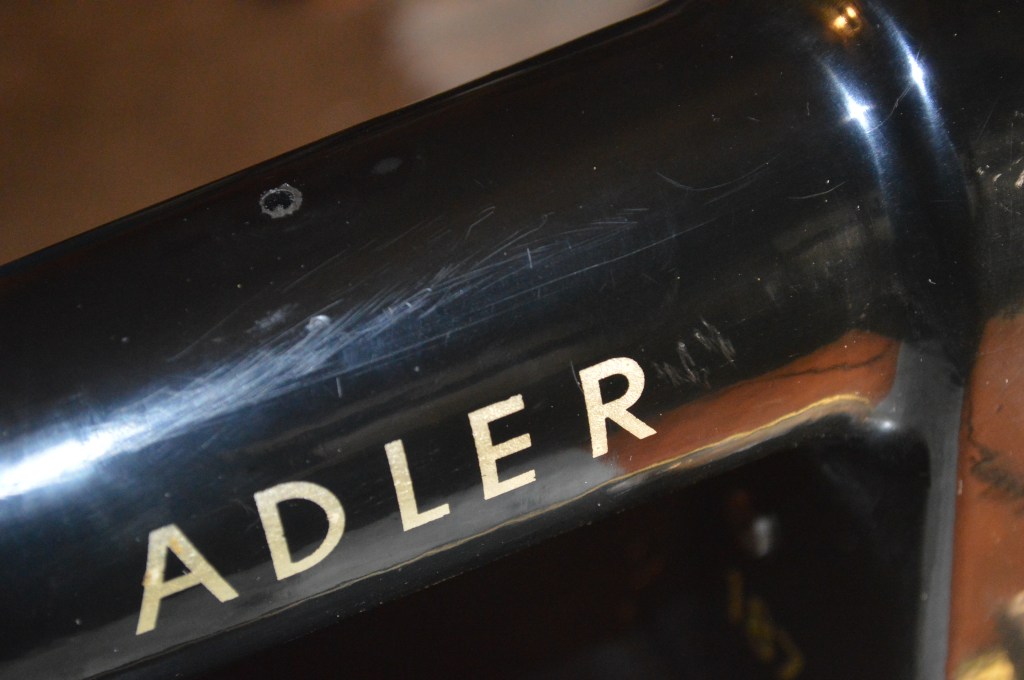

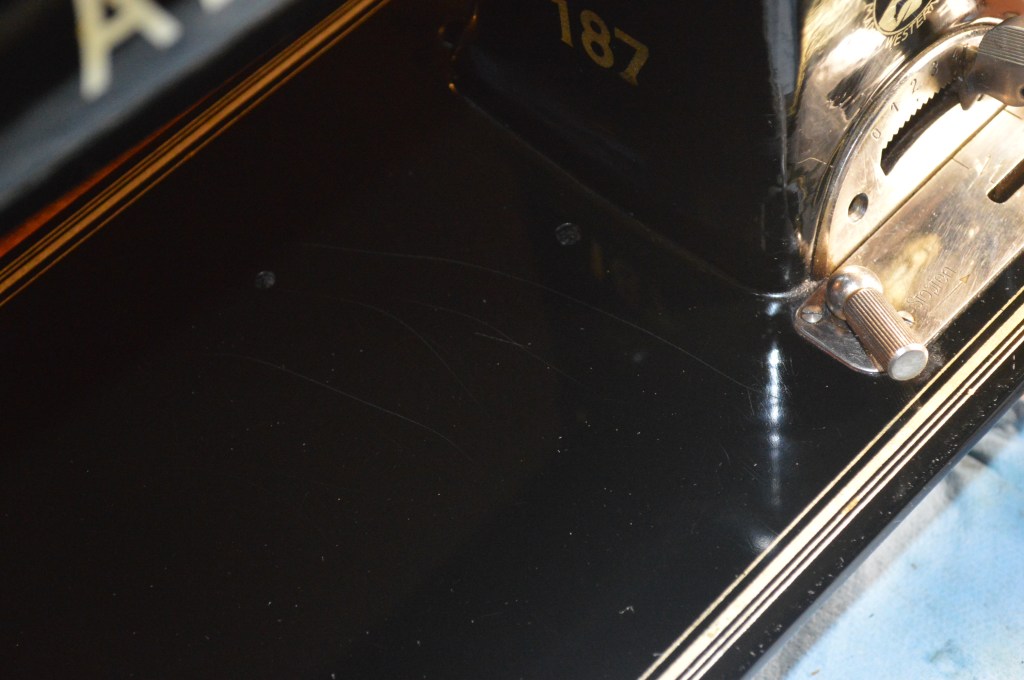

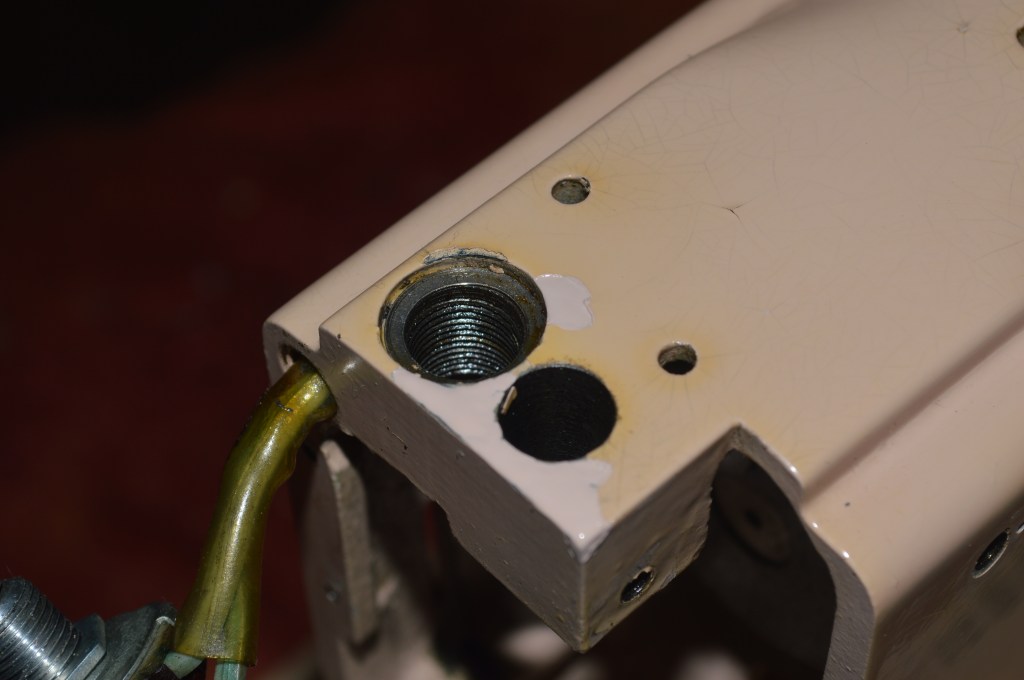

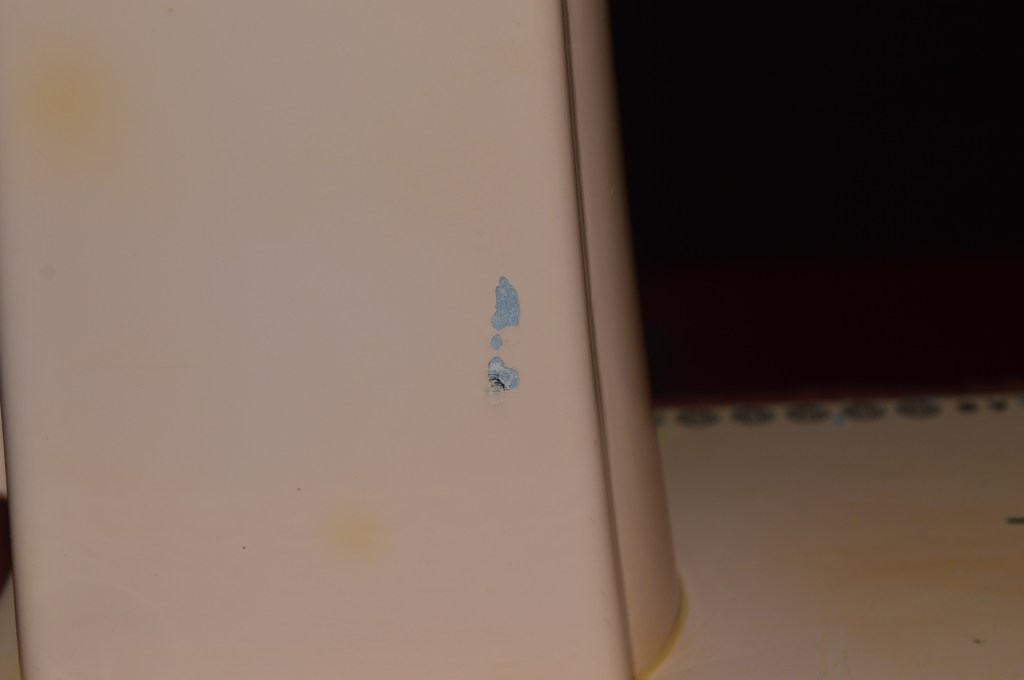

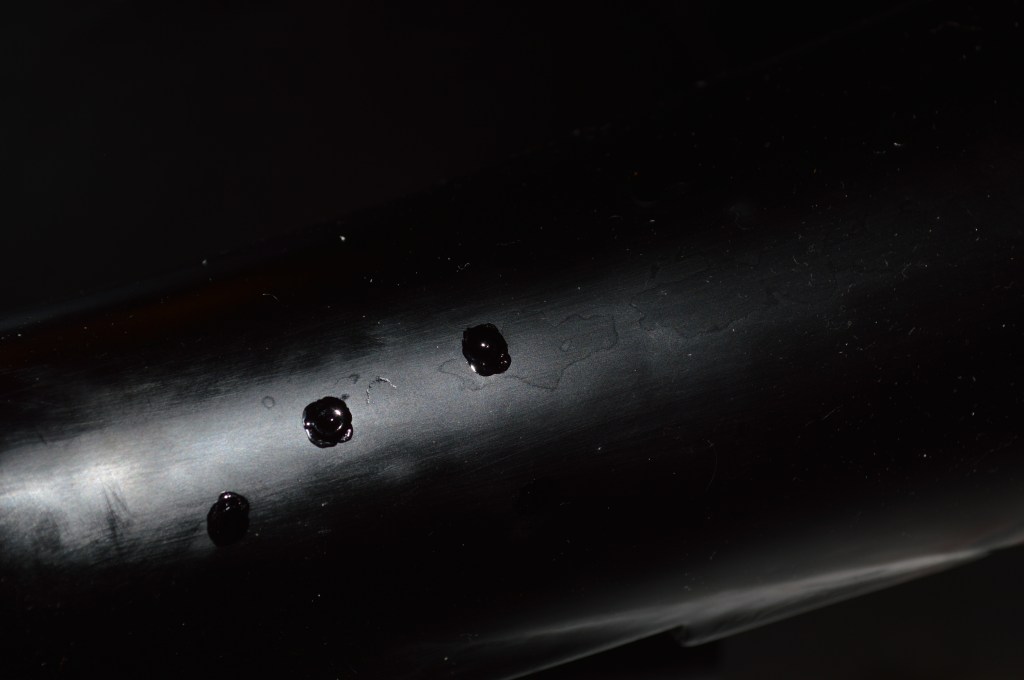

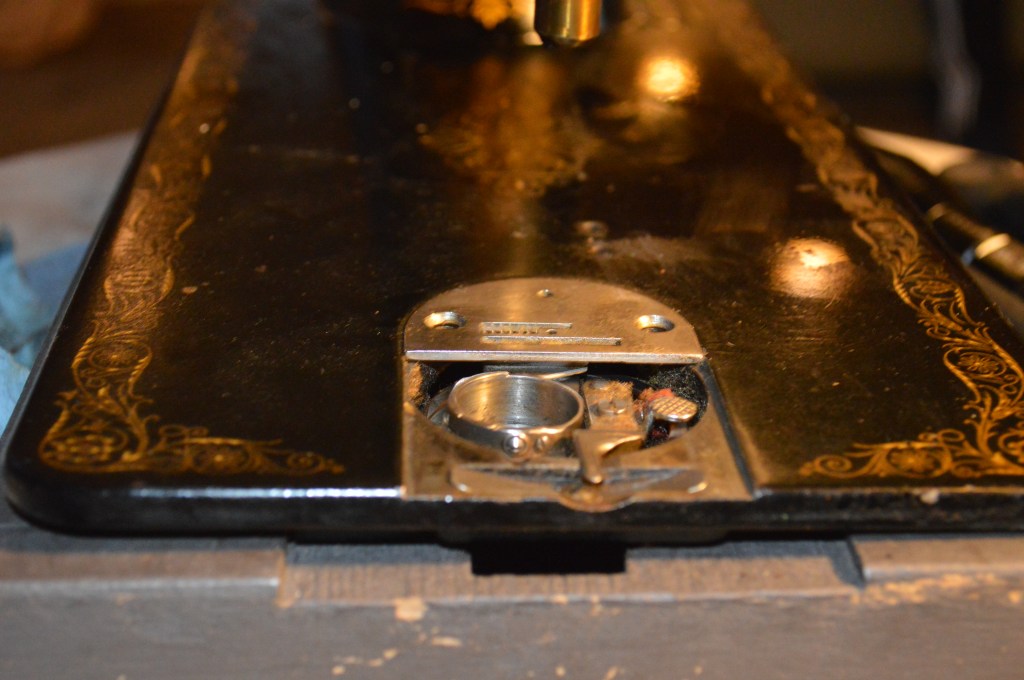

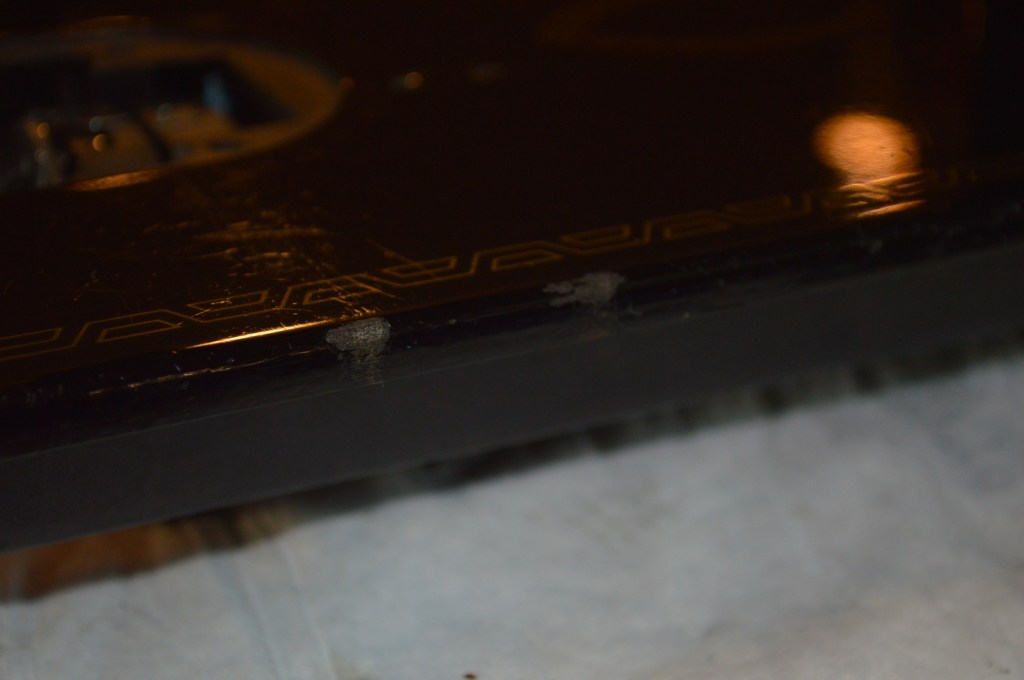

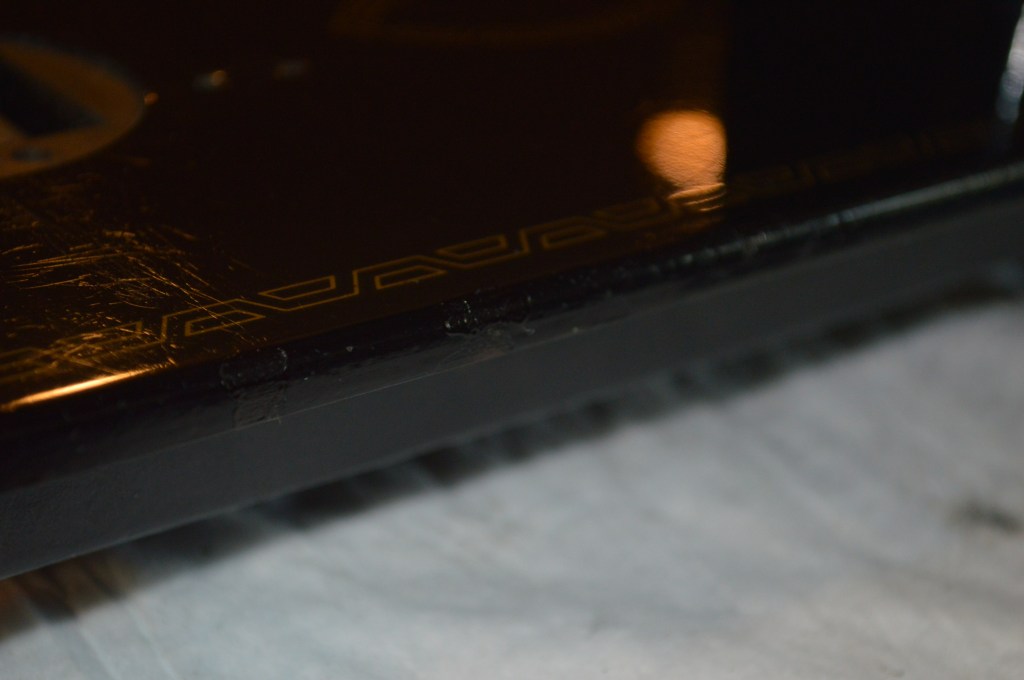

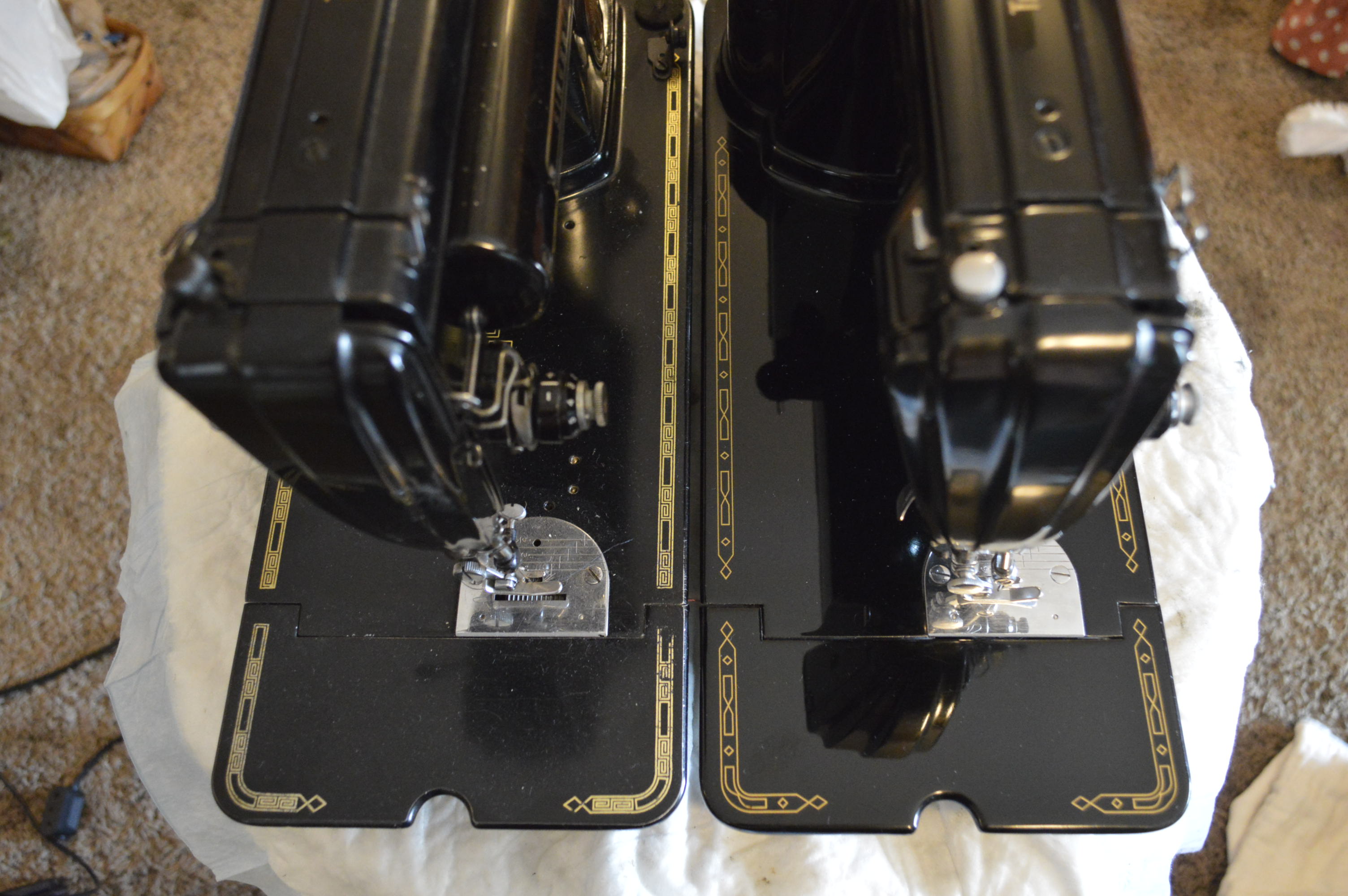

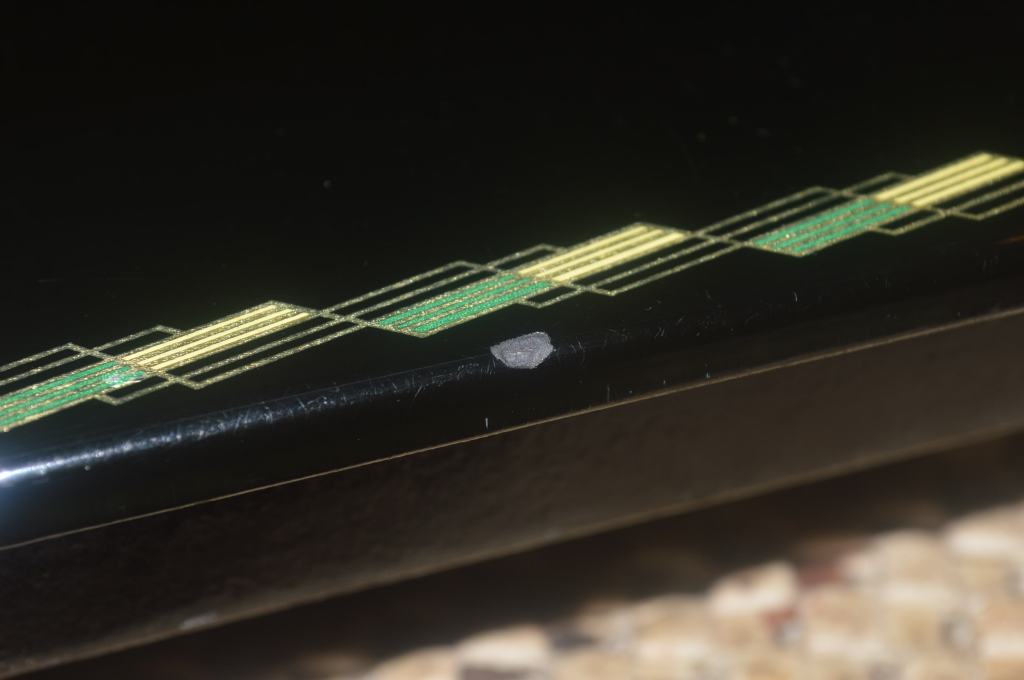

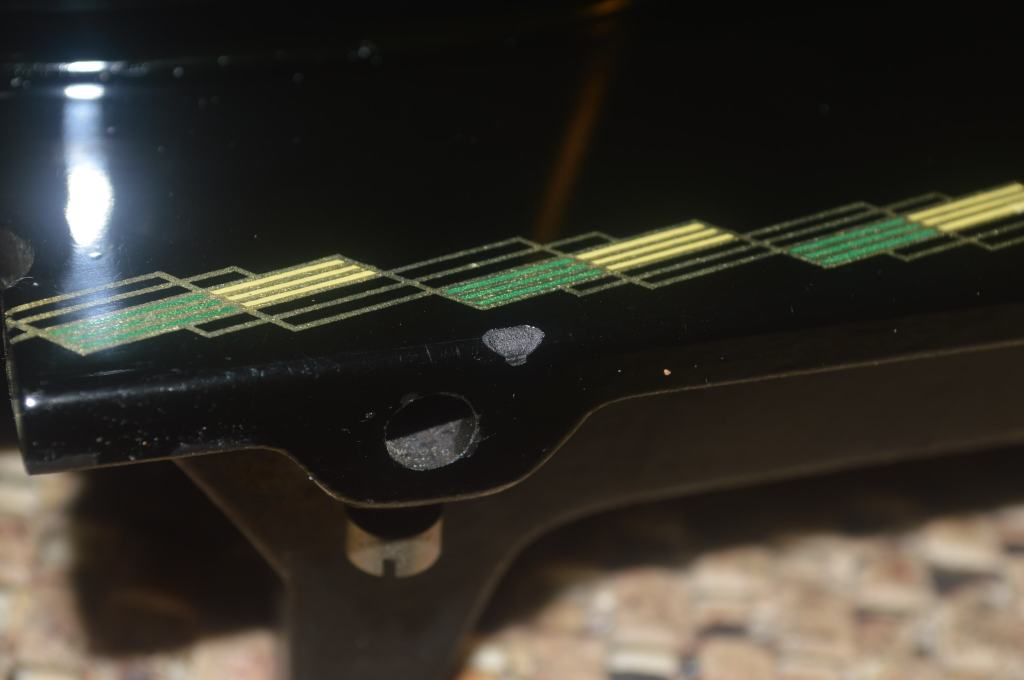

.The machine looks pretty good, but here is where the paint is damaged.

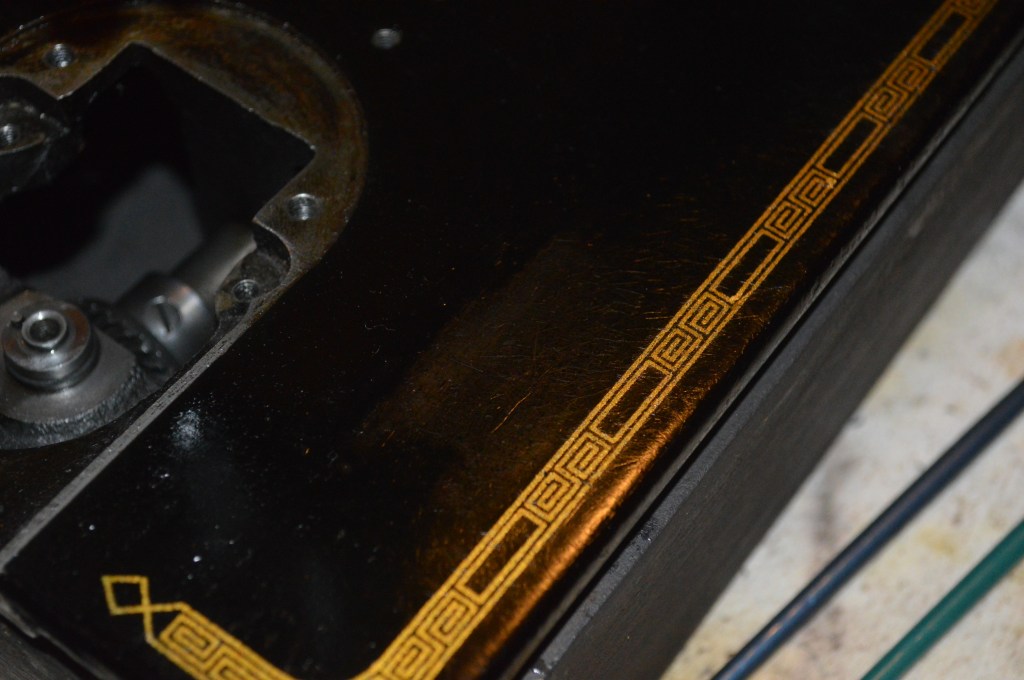

The scars on the sewing machine arm are too big to get a nearly invisible repair. Fortunately, the location is such that they are not “in your face” when seated in front of the machine. Paint matching will effectively make them far less obvious. The chips on the bed are another story.

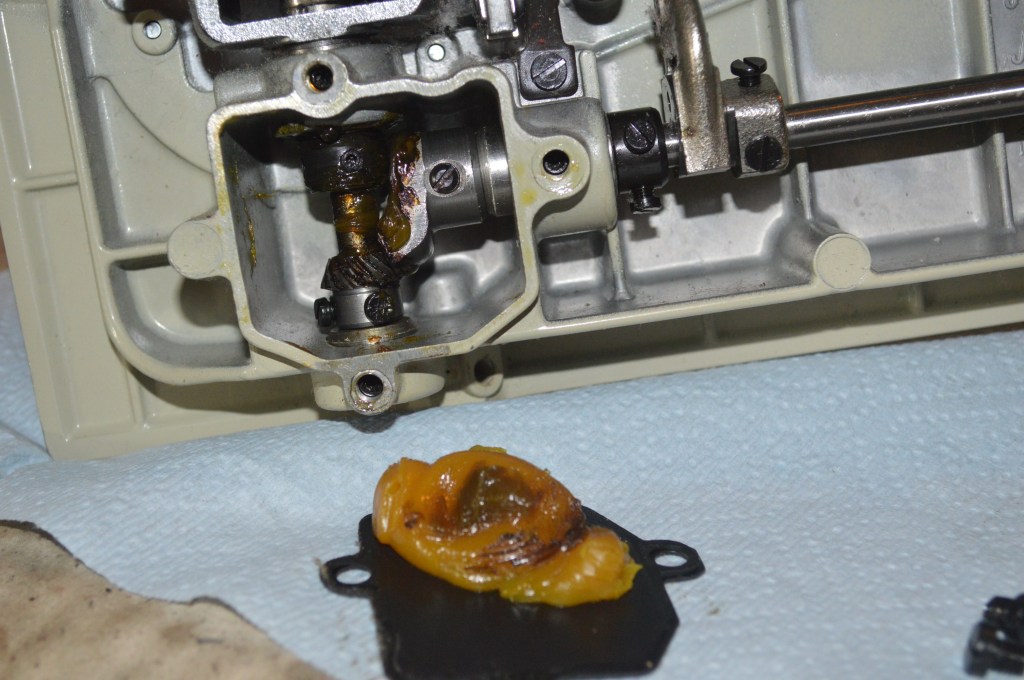

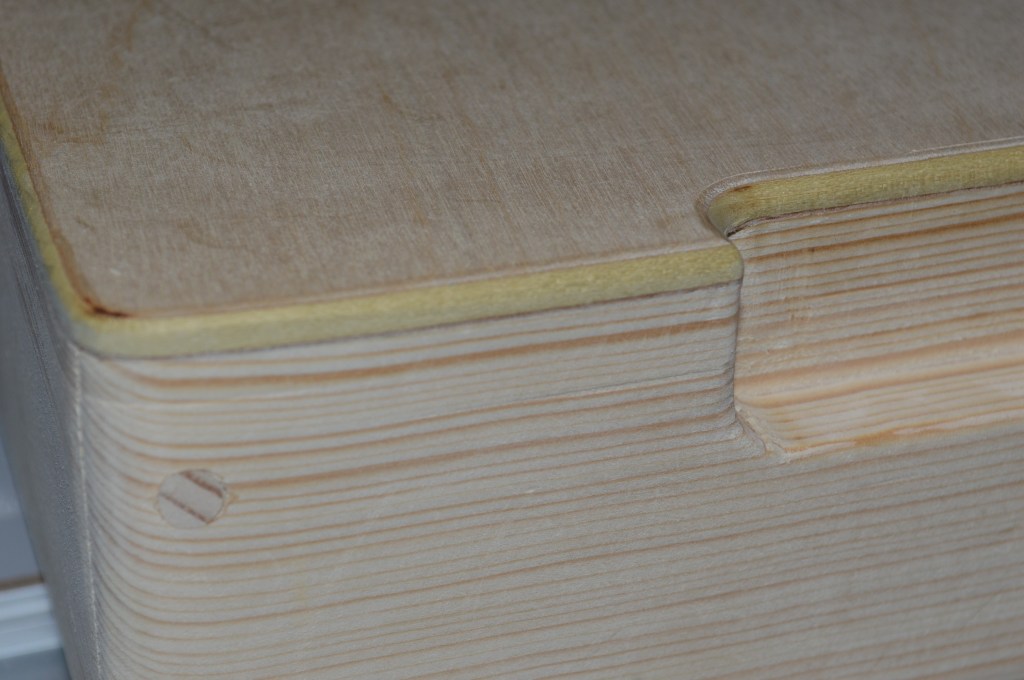

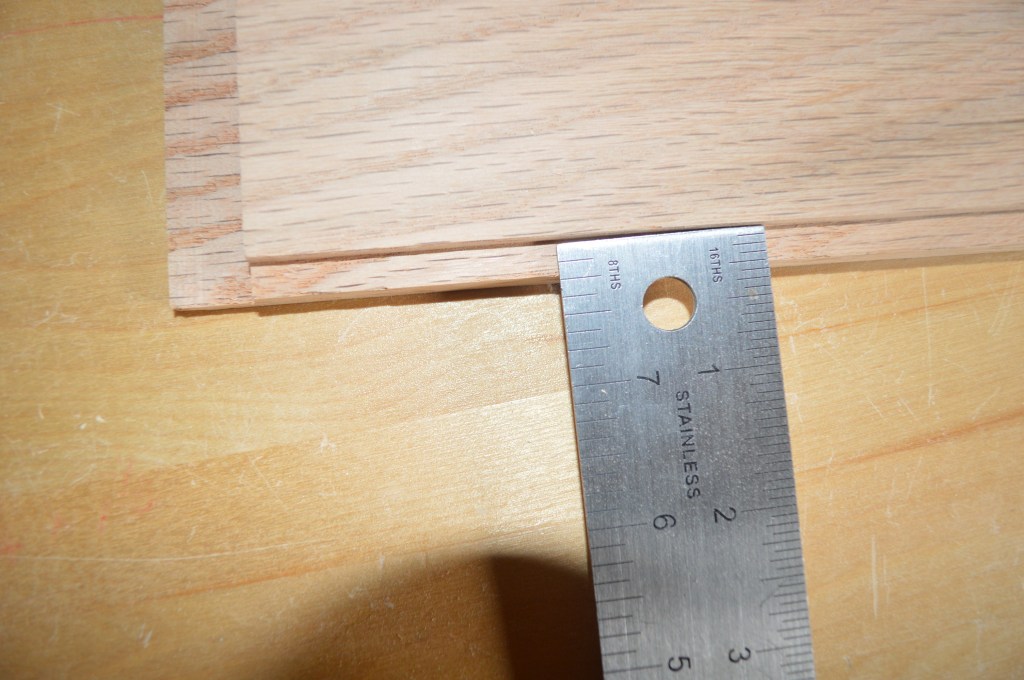

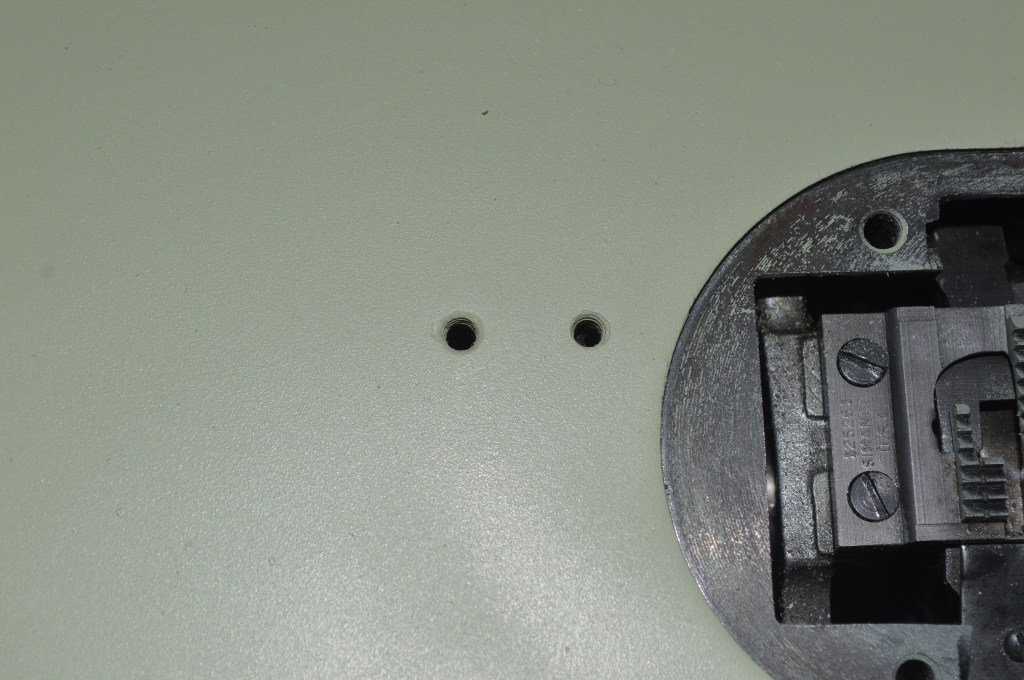

The bed chips are deep and go thru to the metal. The paint thickness is relatively thick here, and because the paint match paint is formulated with shellac, which is relatively thin, it will need to be built up over successive applications. Each application will need to dry before the next application. Instead of seperating the cosmetic from the mechanical restoration, it will be done in steps that are done concurrently. First, the machine is disassembled to the greatest extent possible.

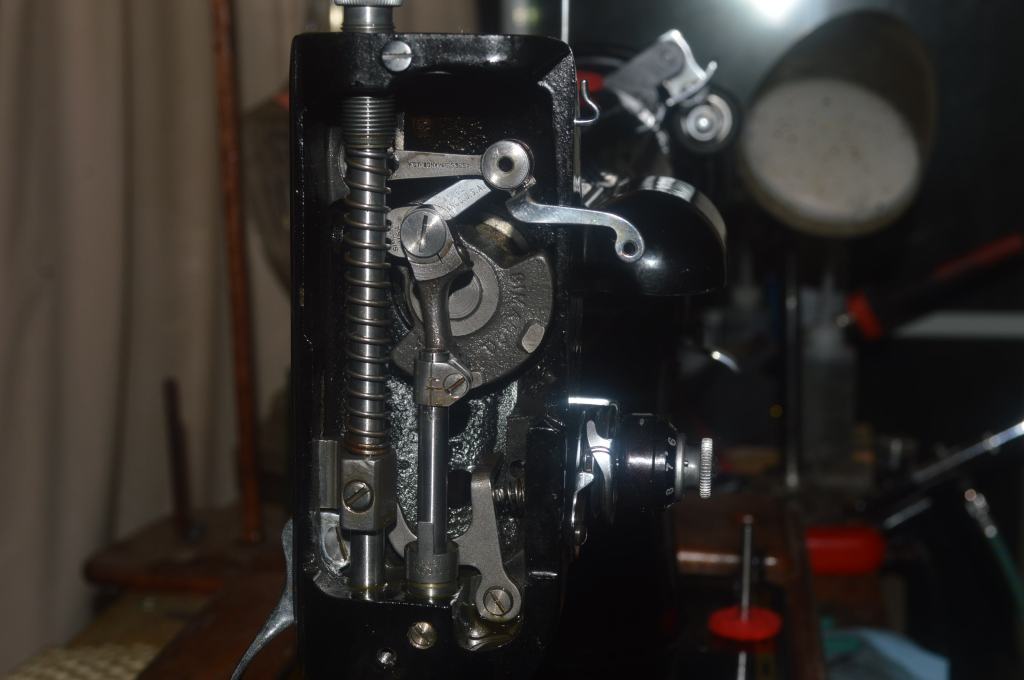

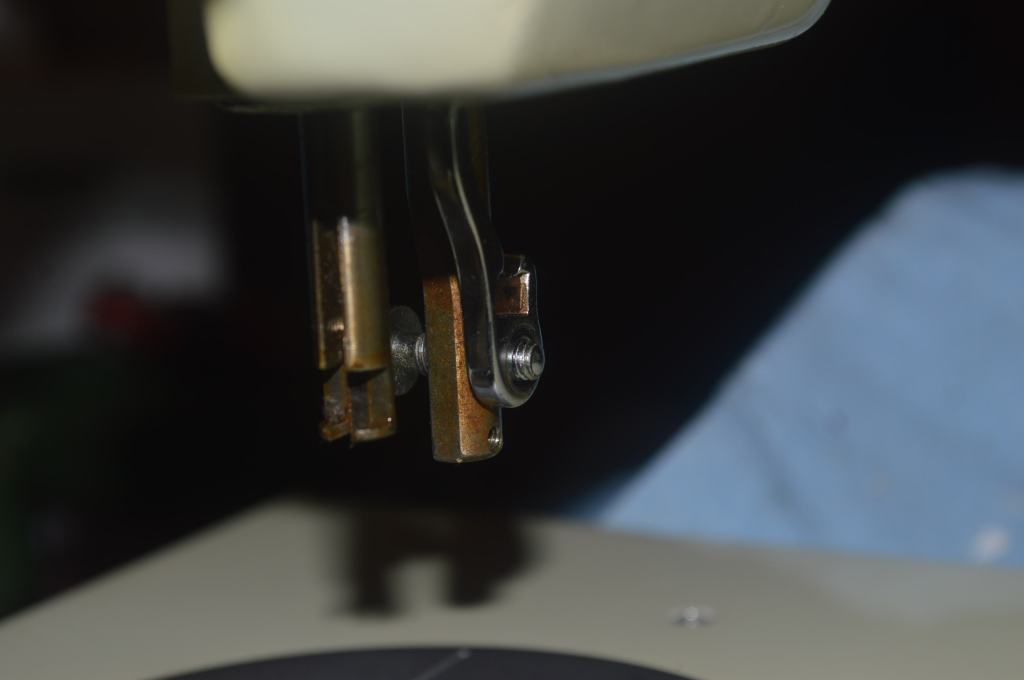

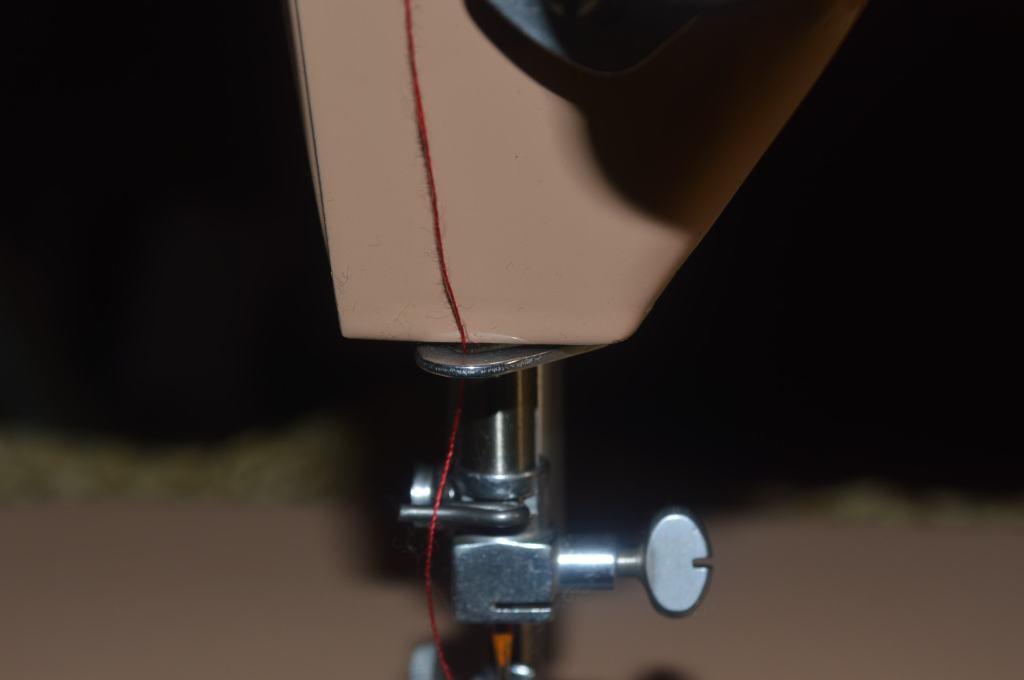

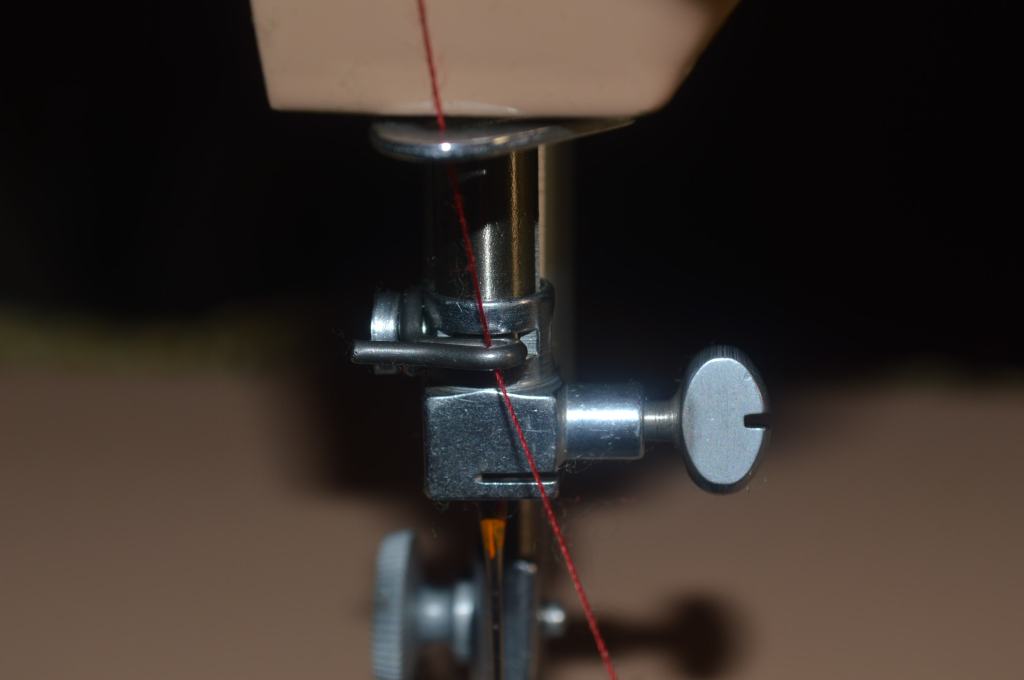

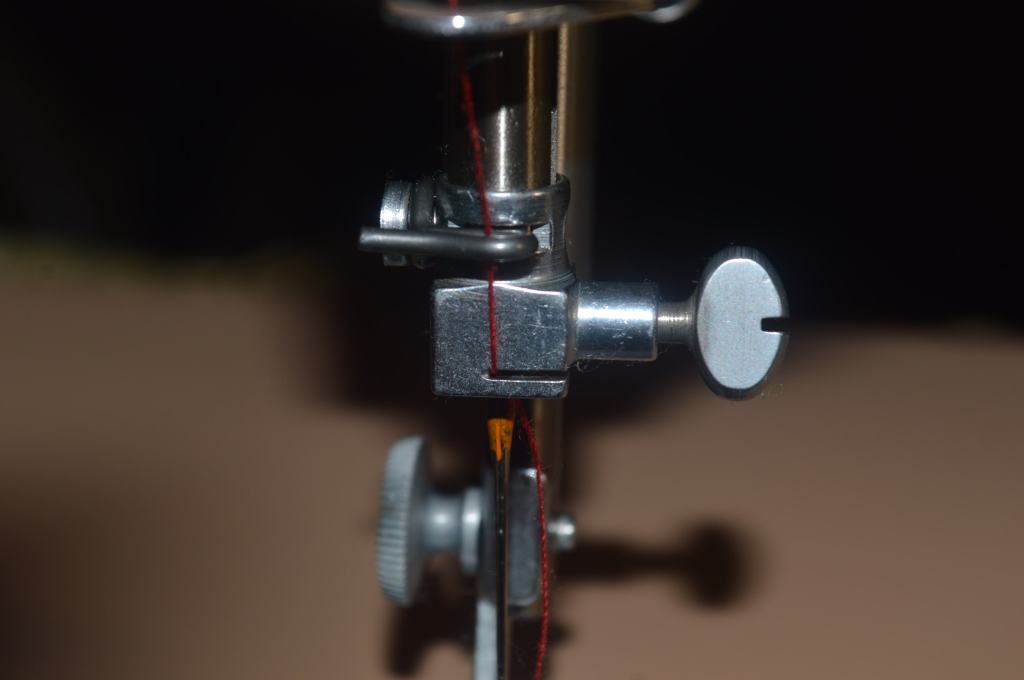

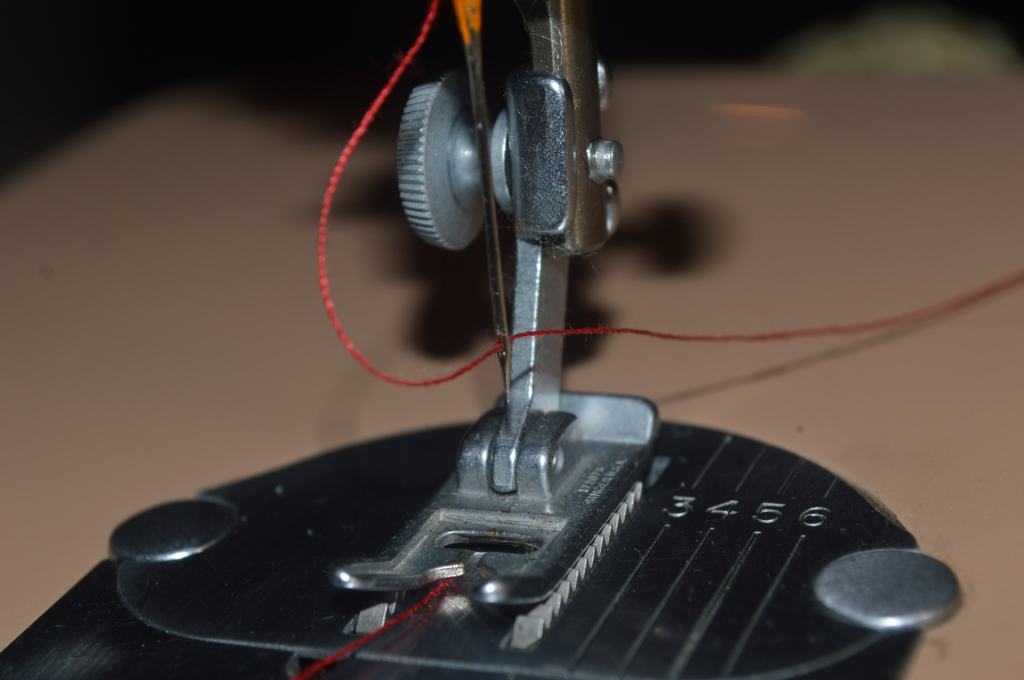

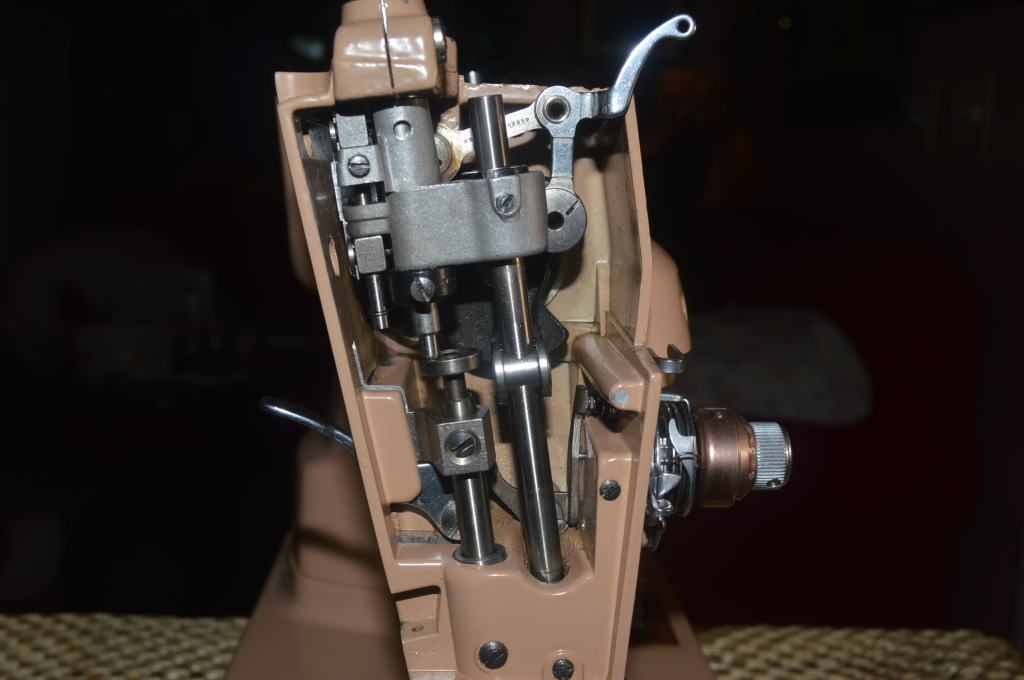

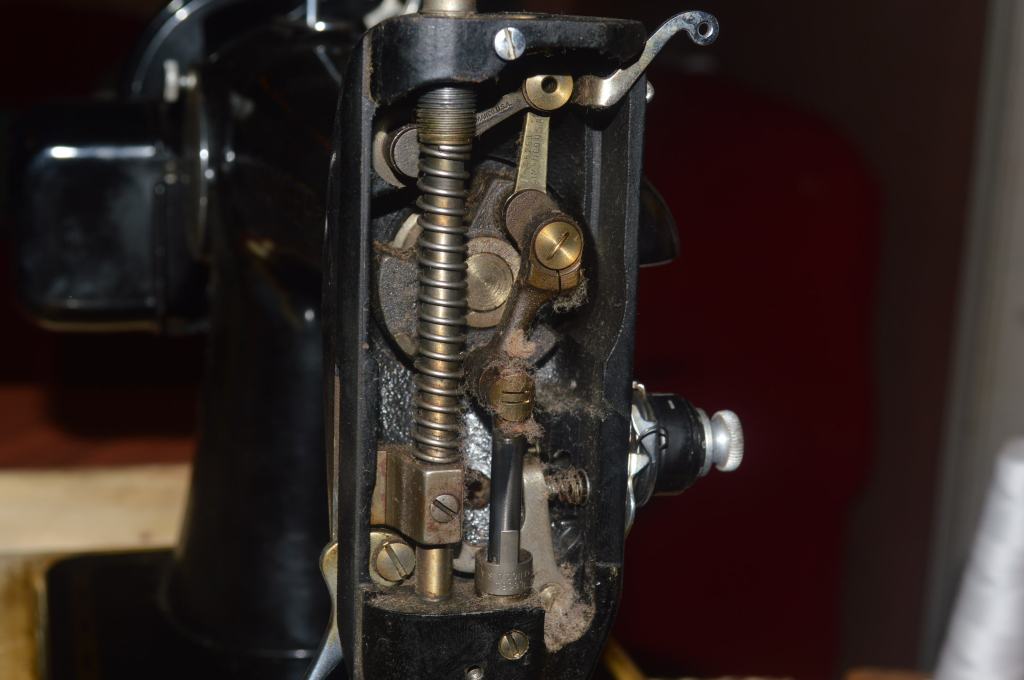

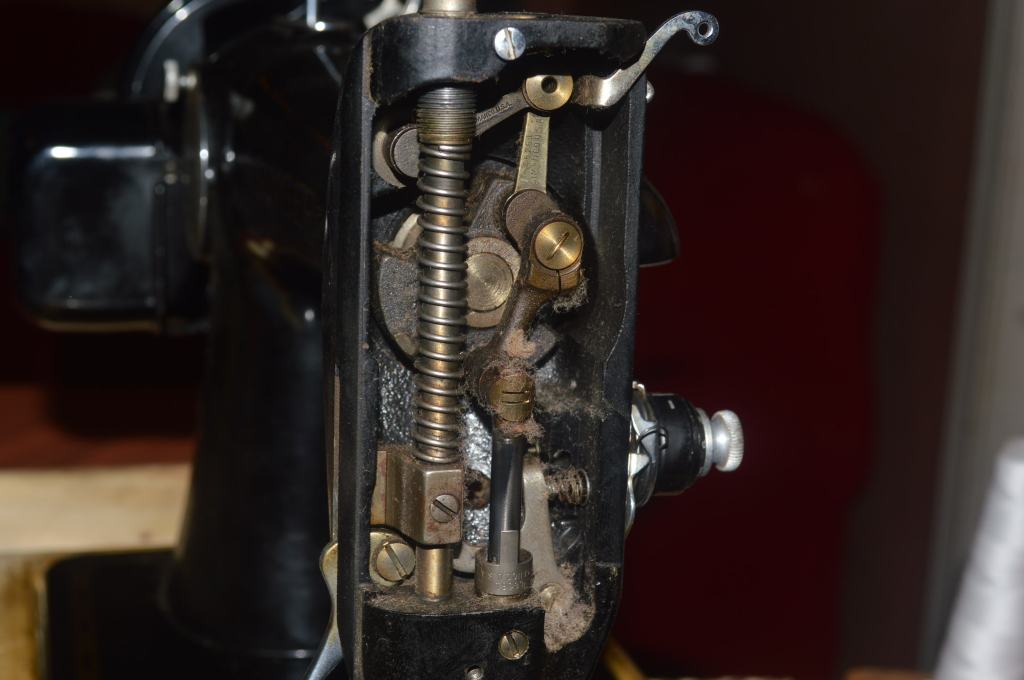

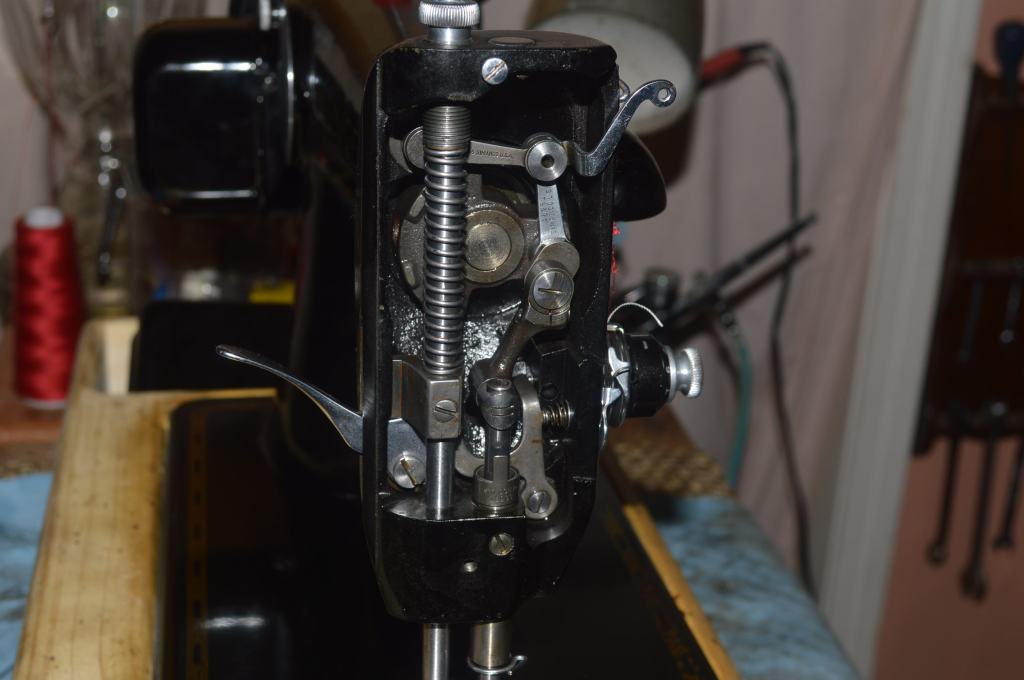

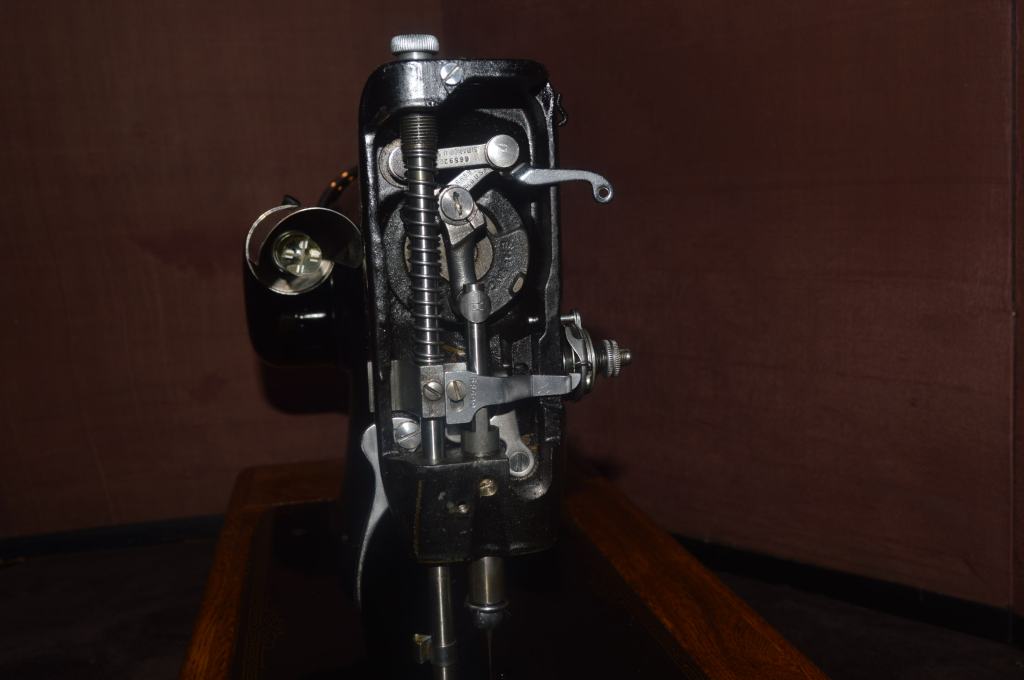

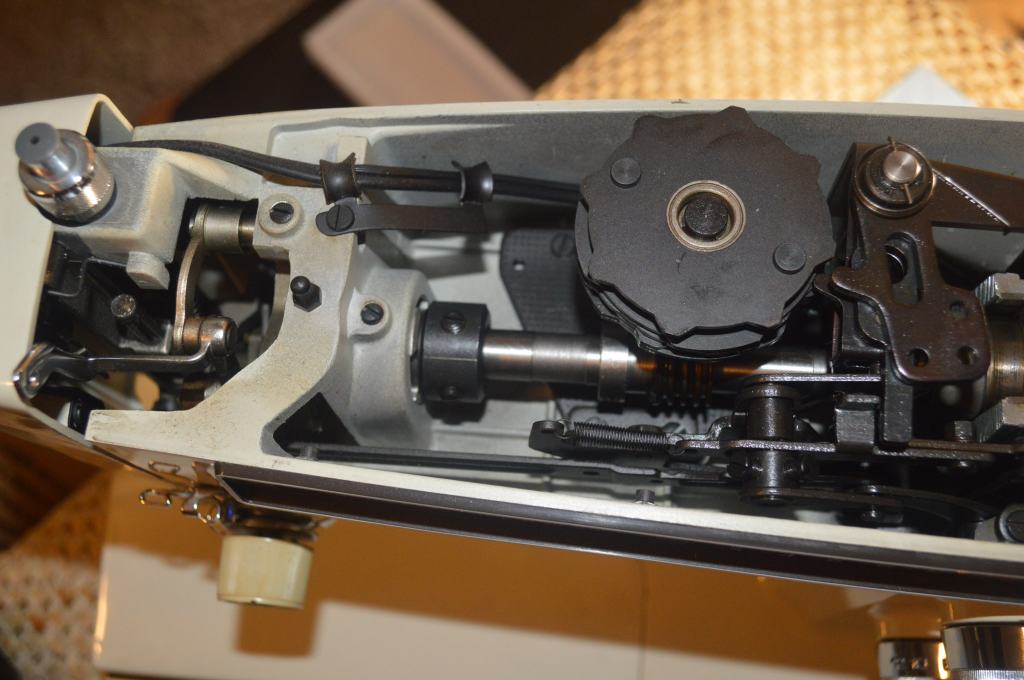

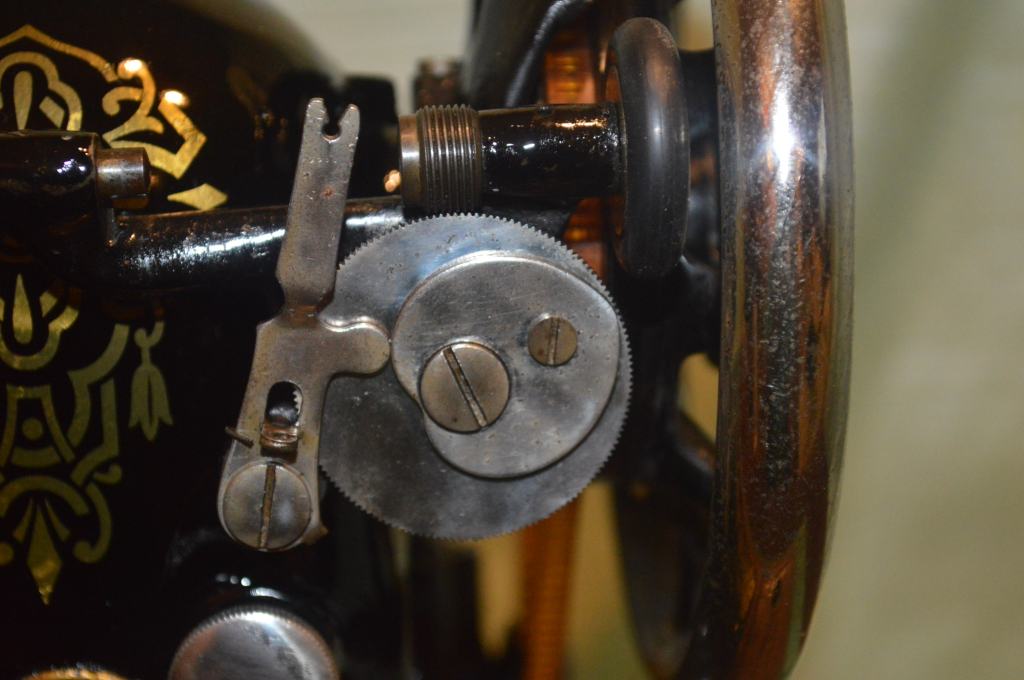

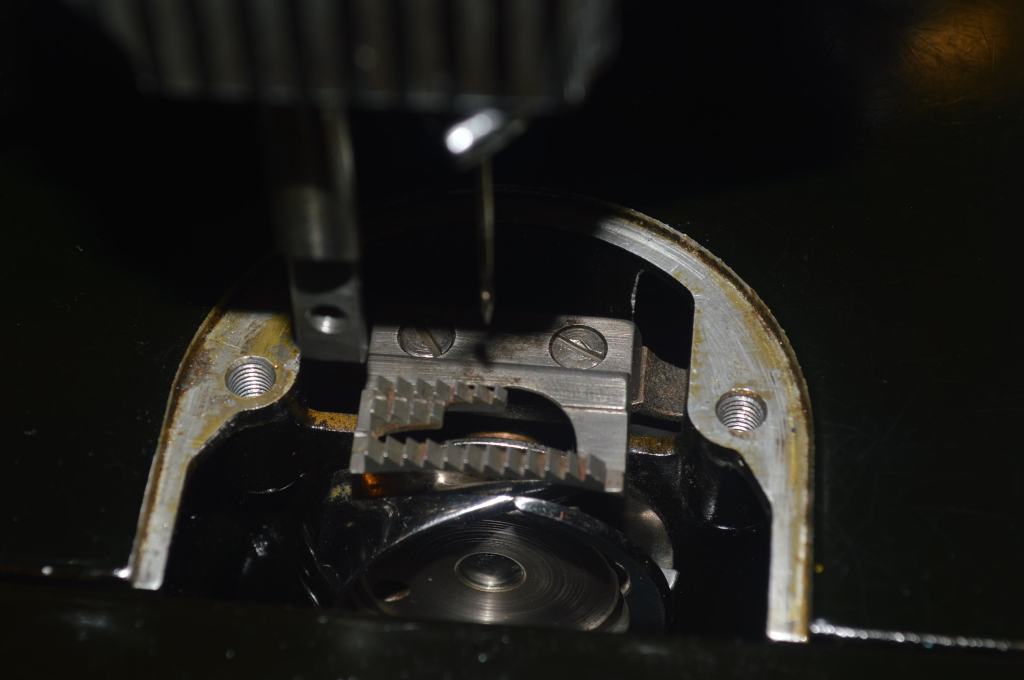

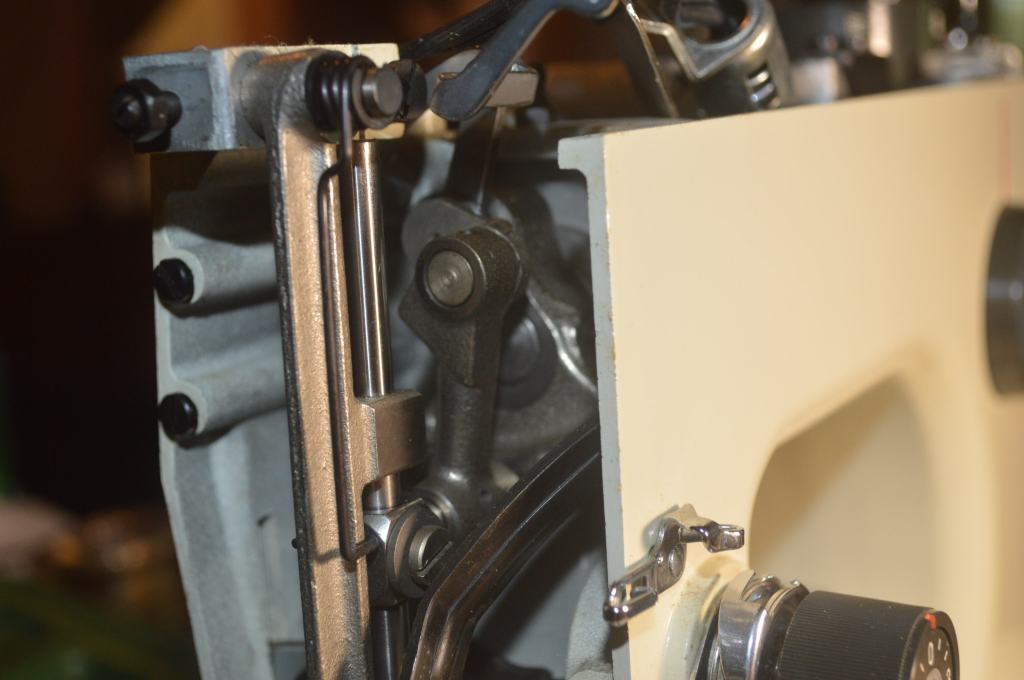

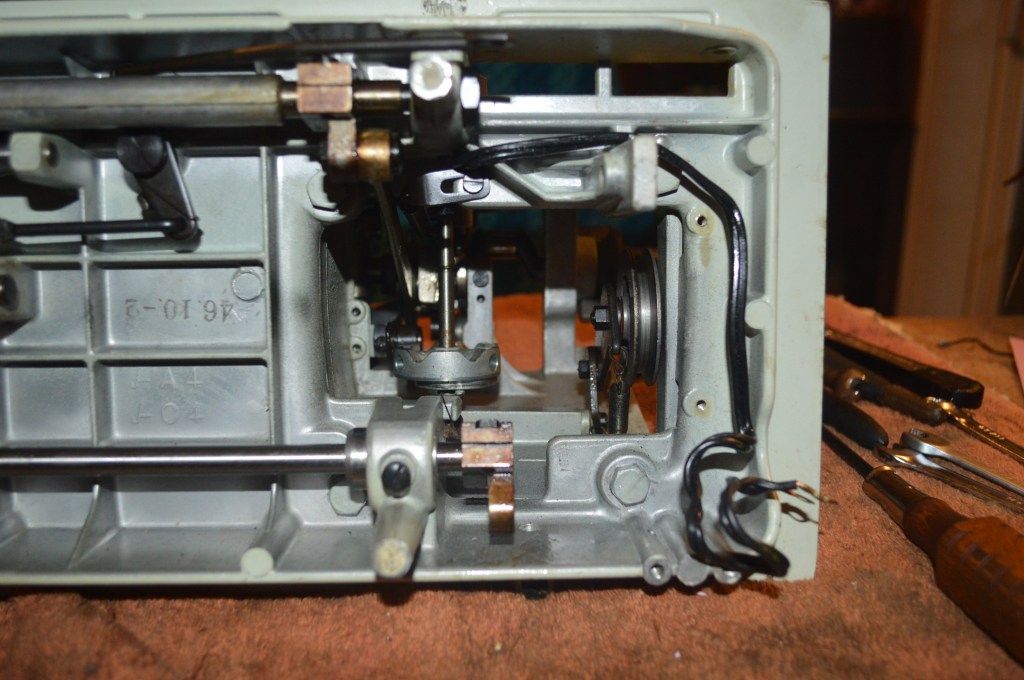

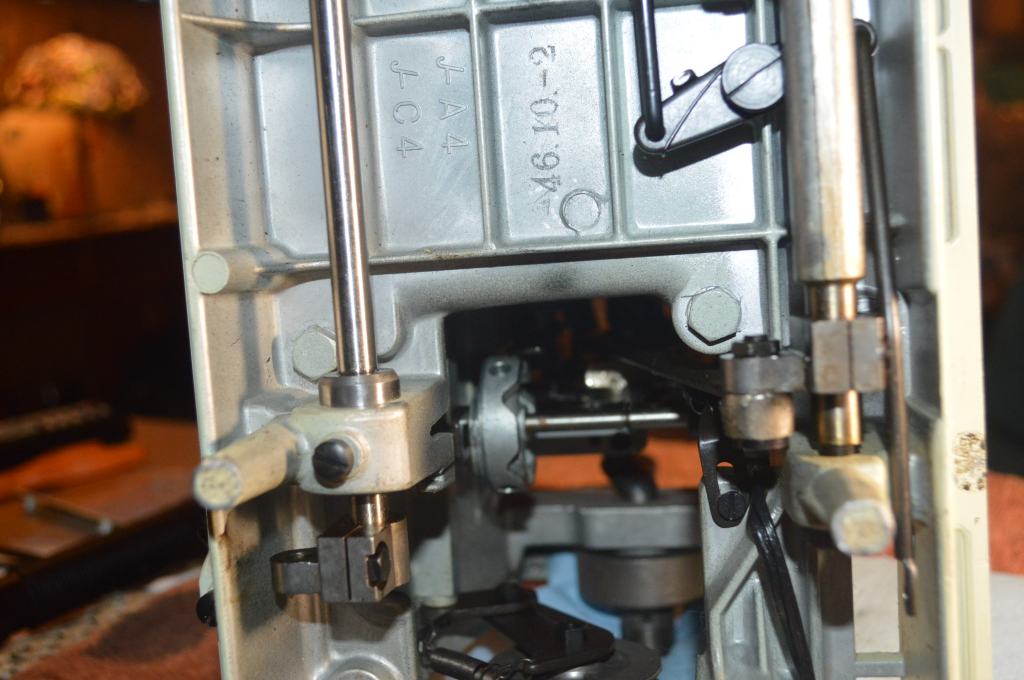

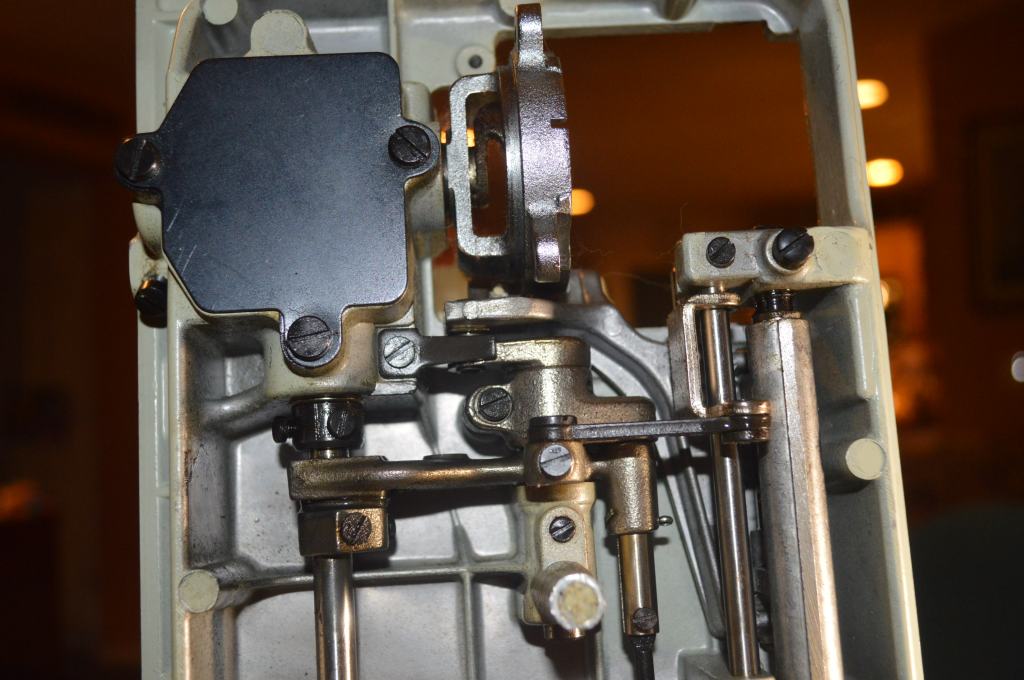

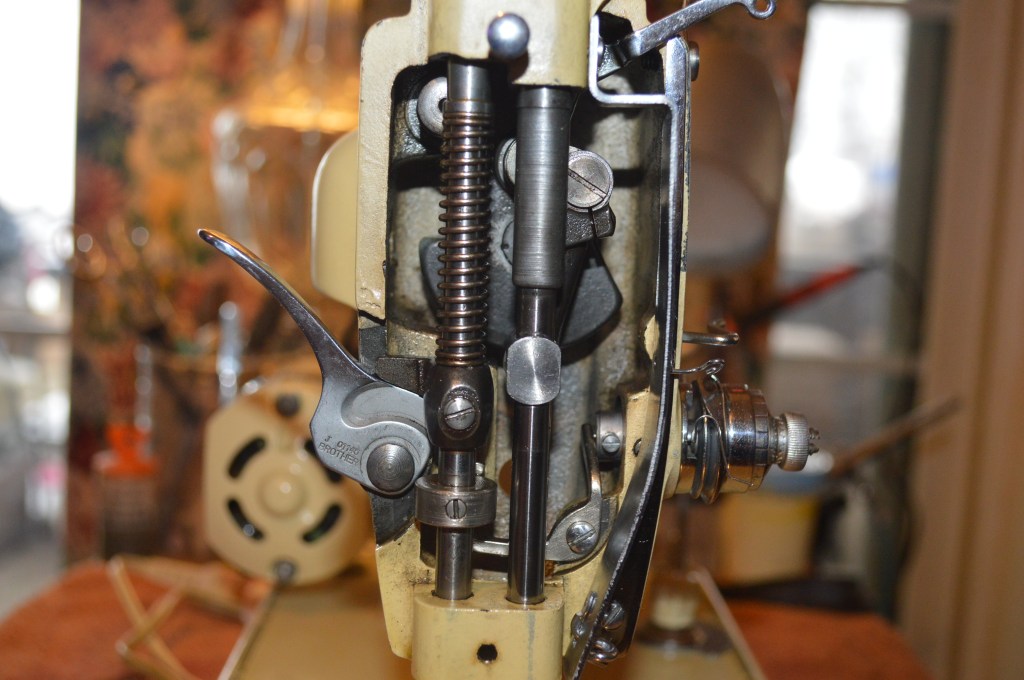

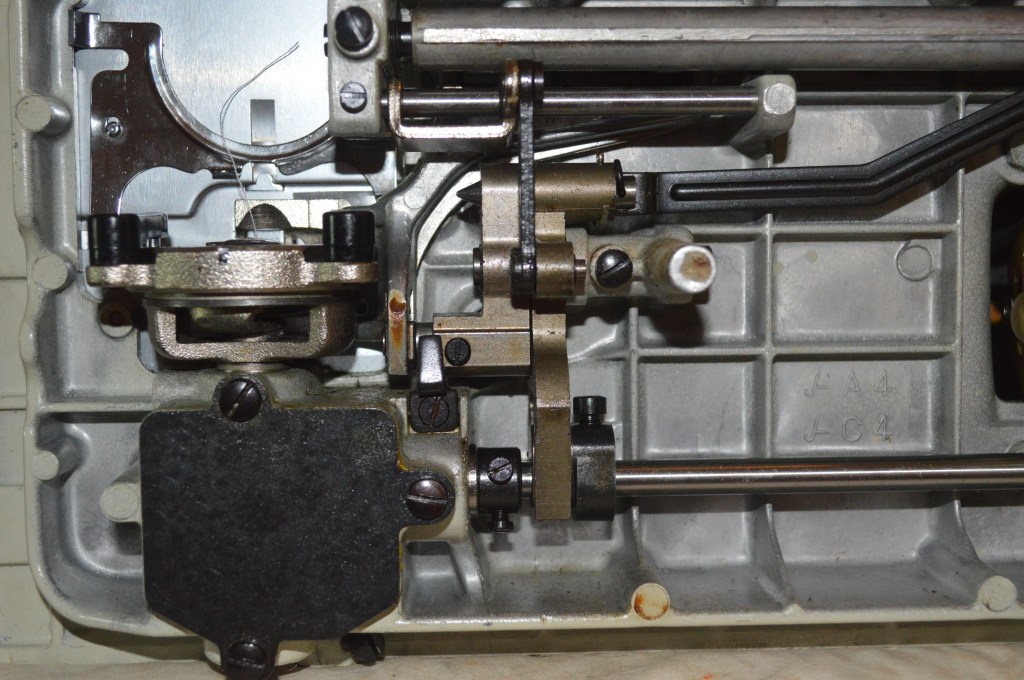

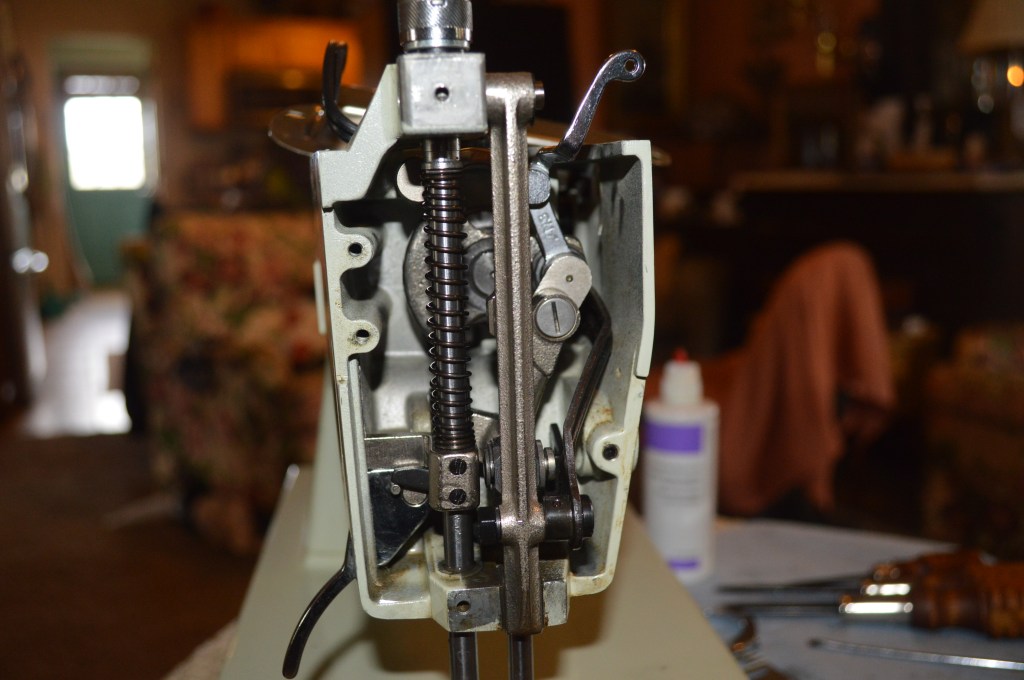

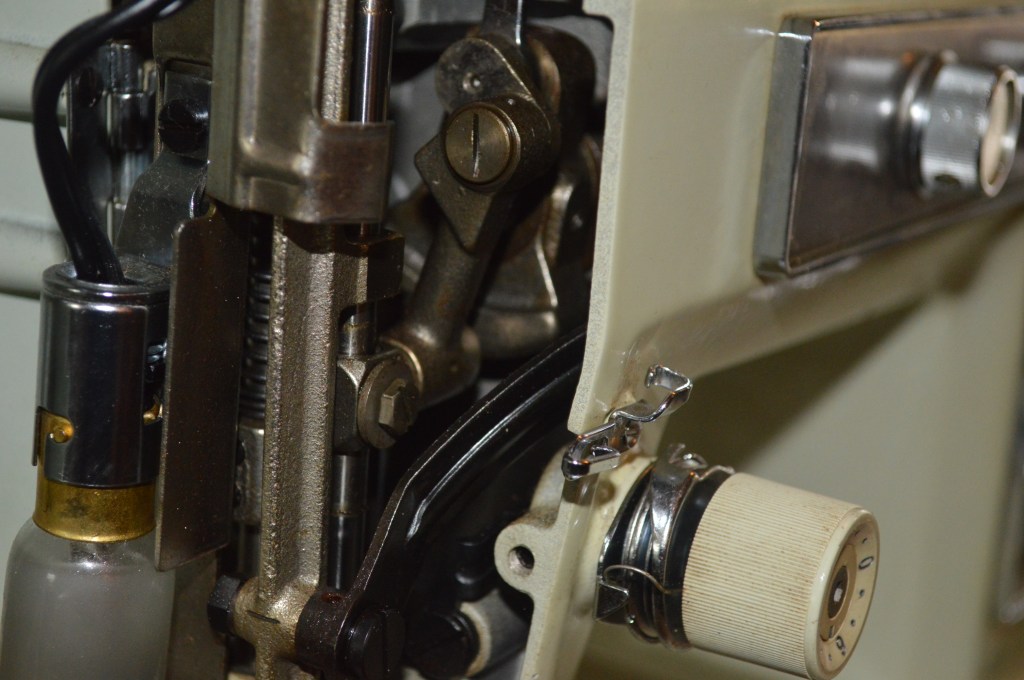

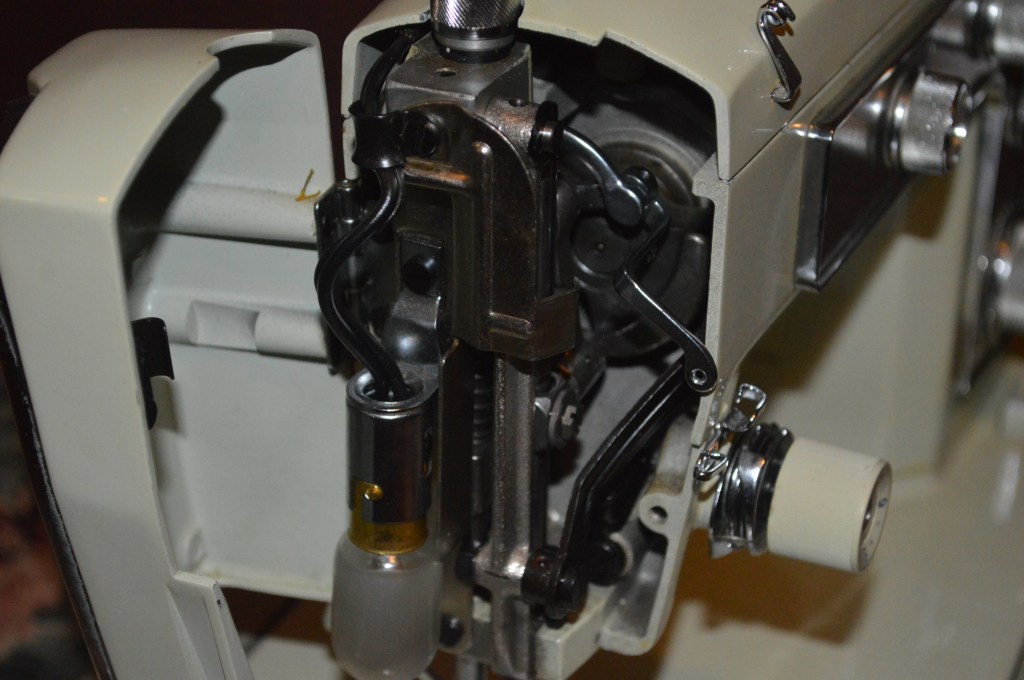

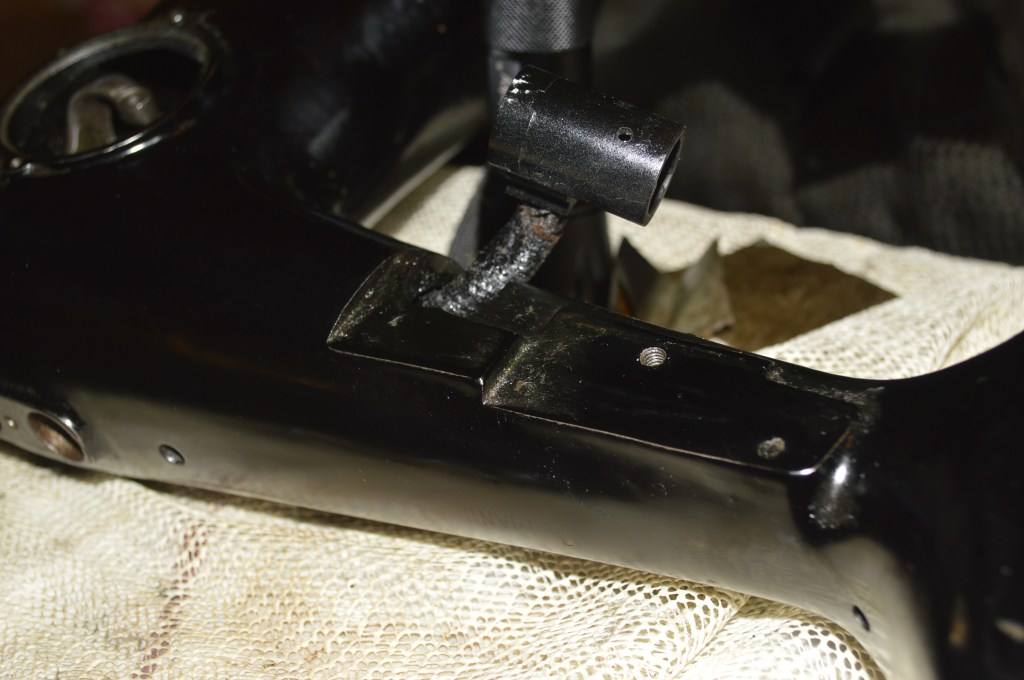

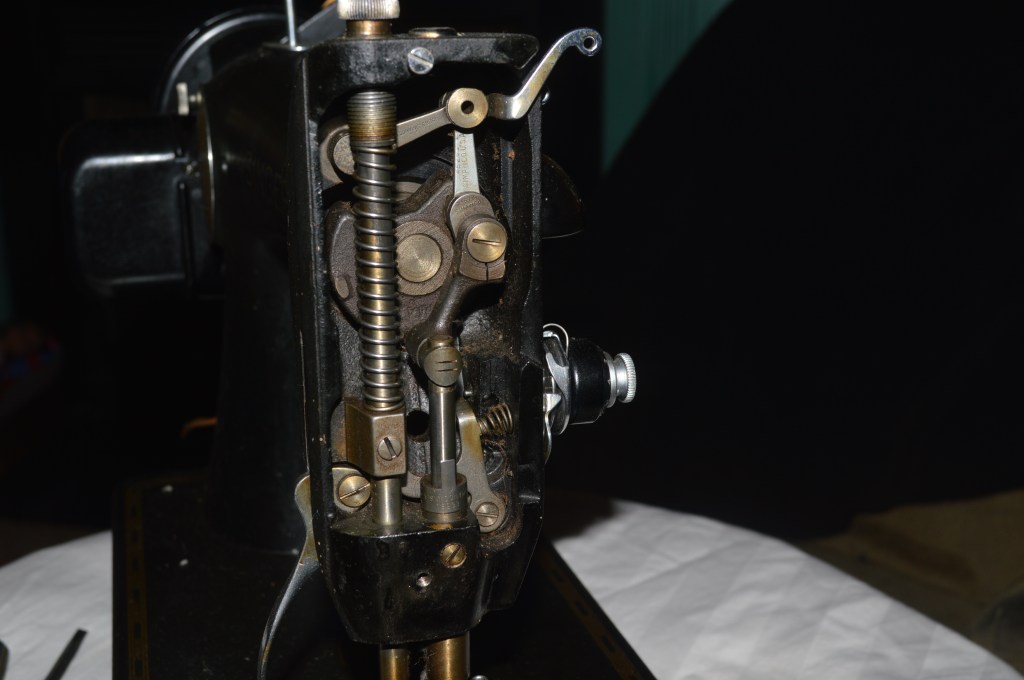

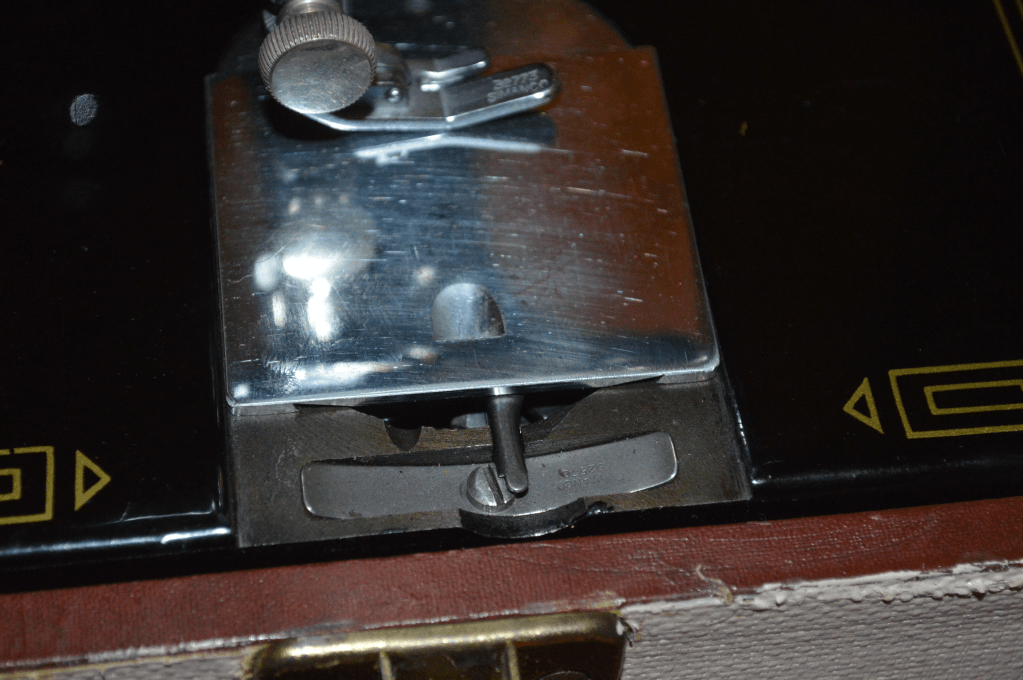

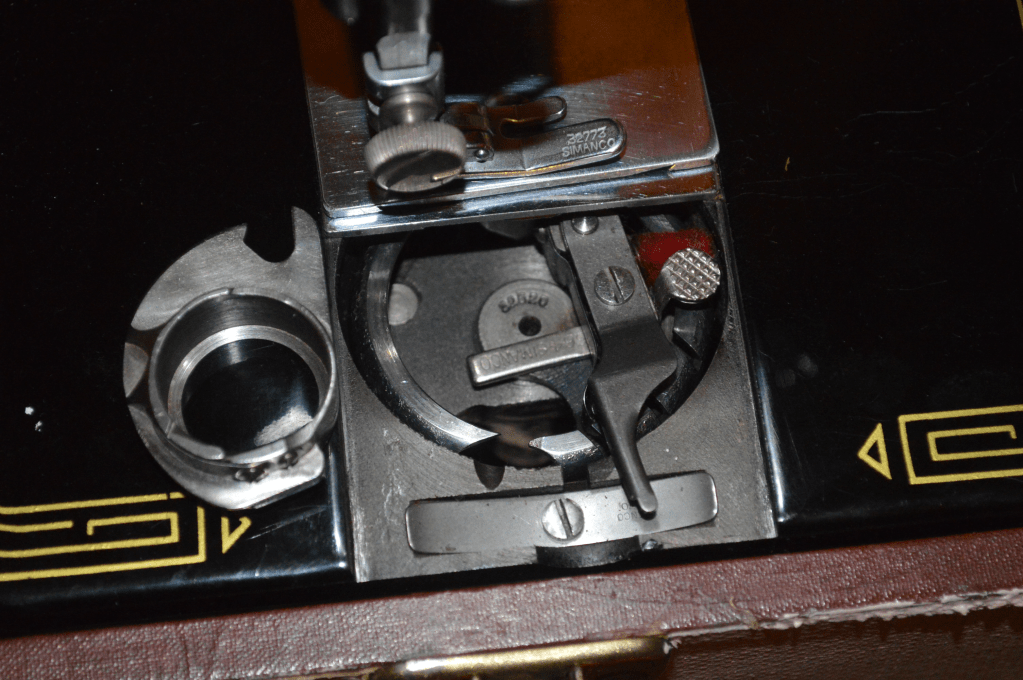

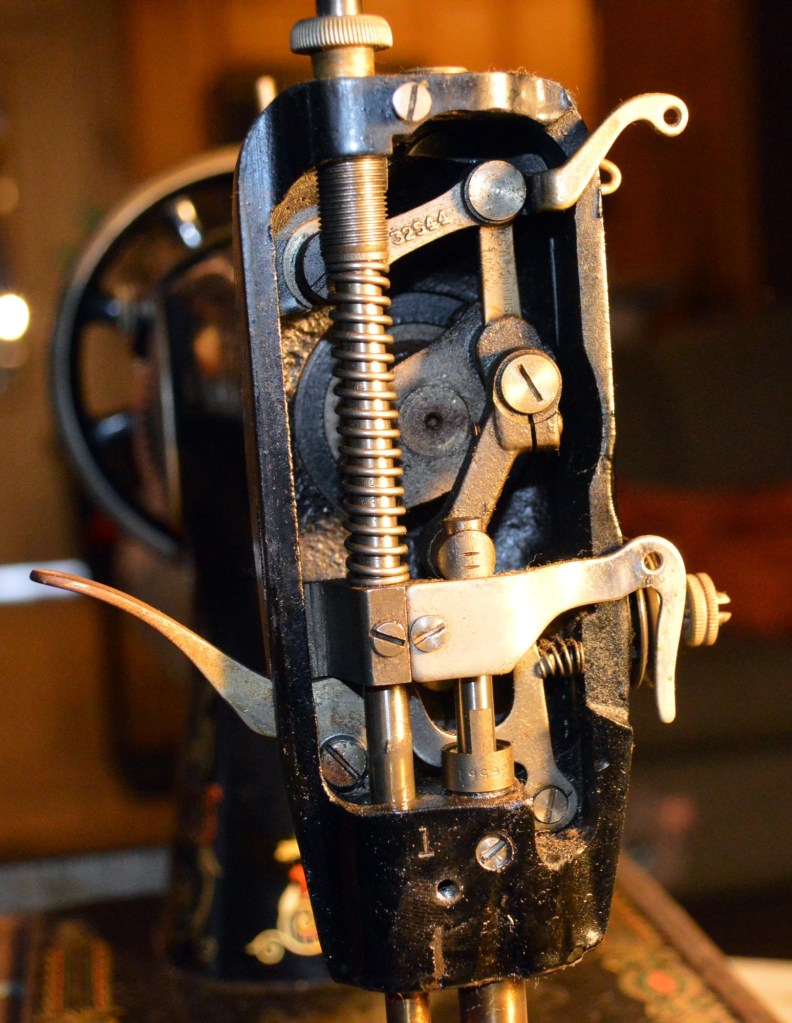

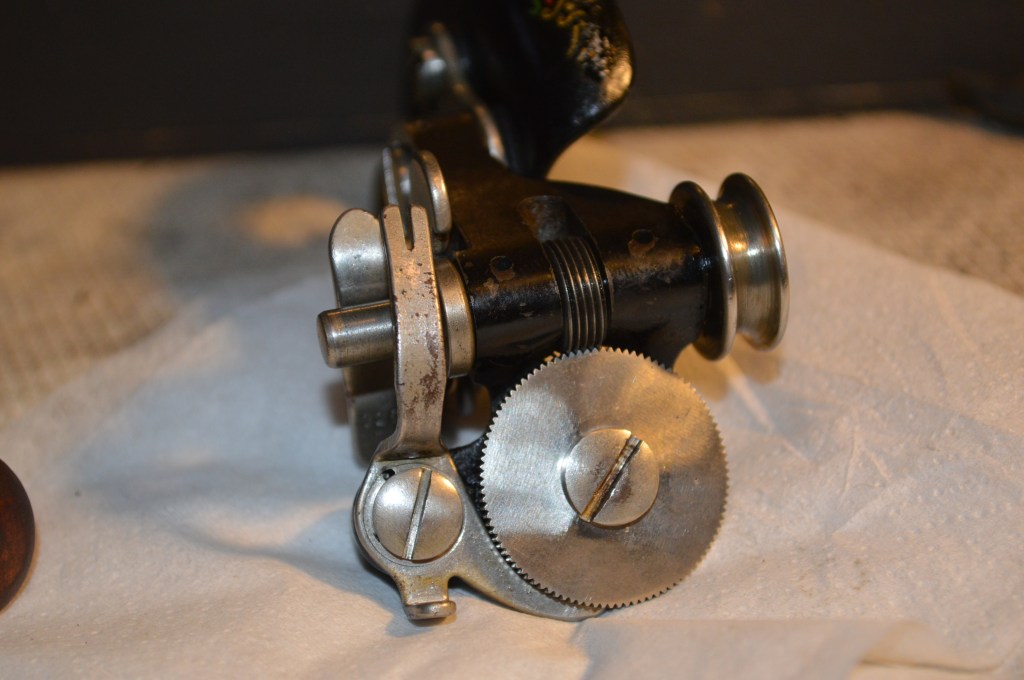

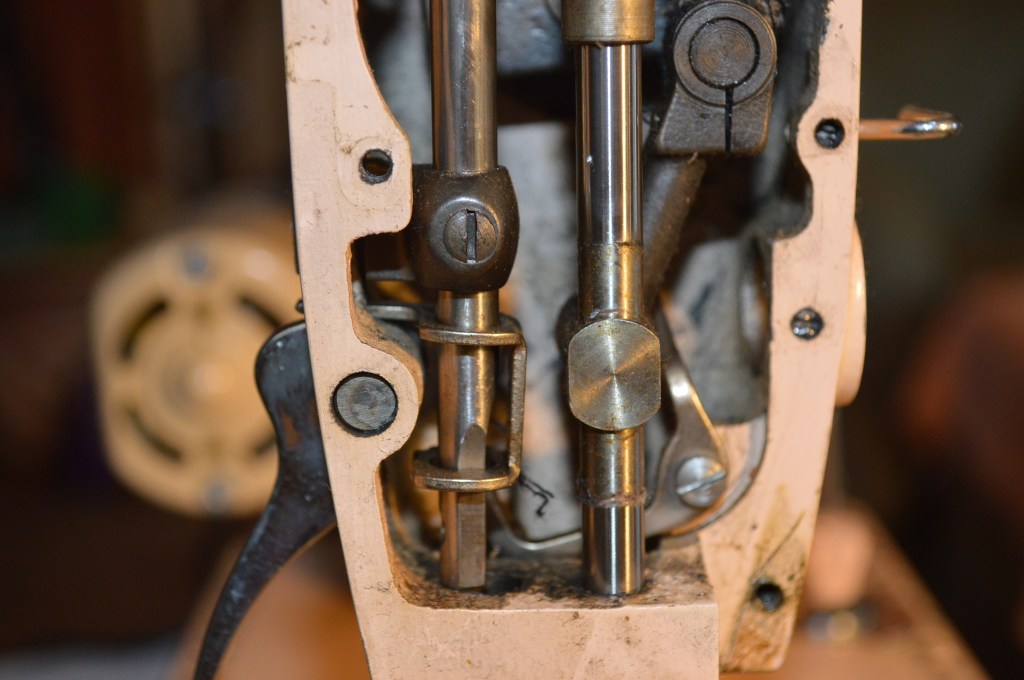

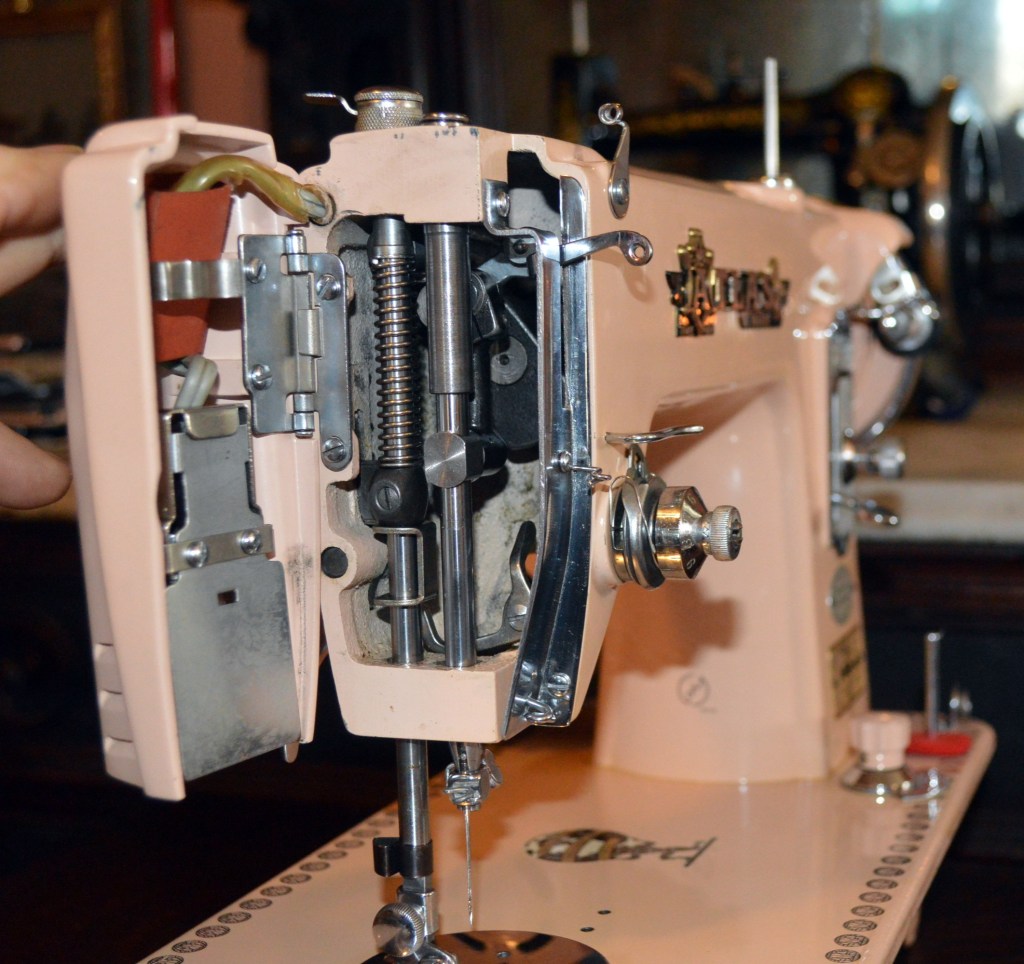

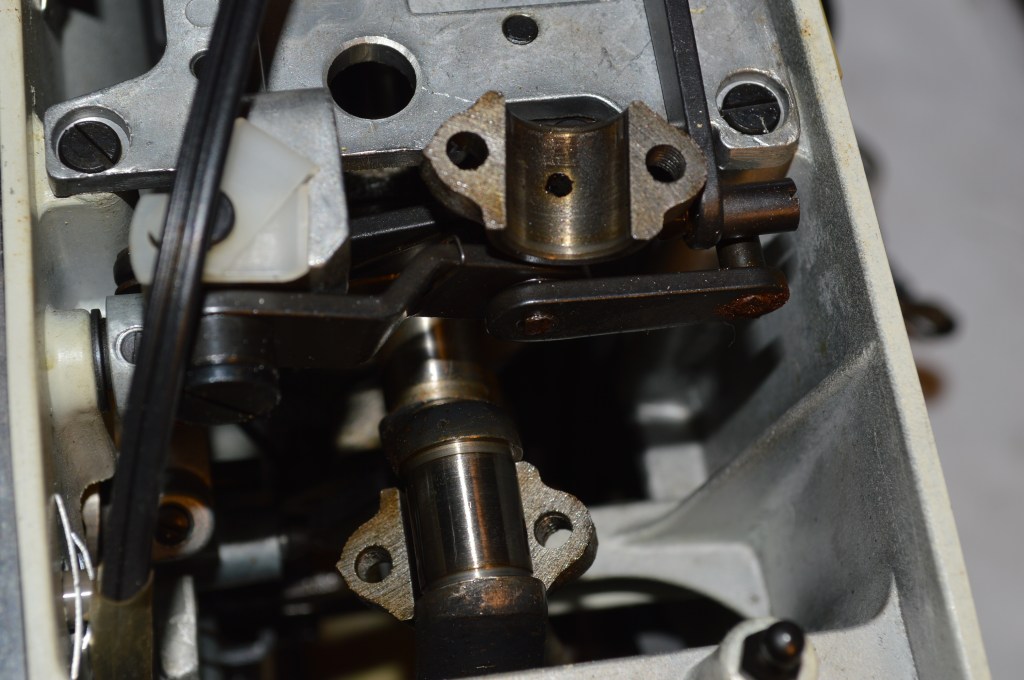

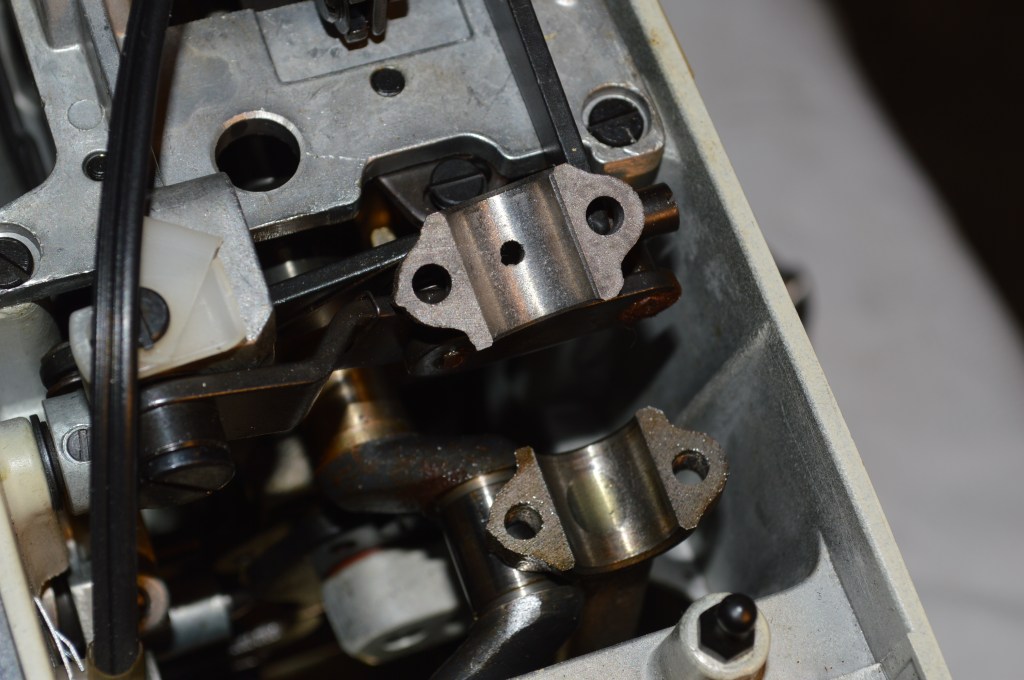

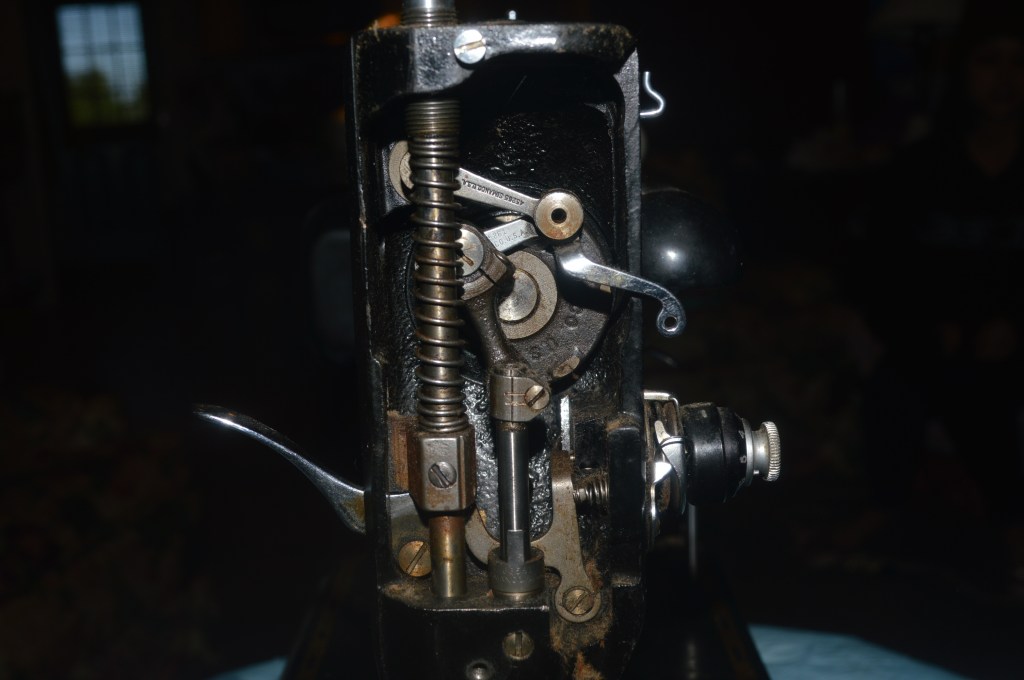

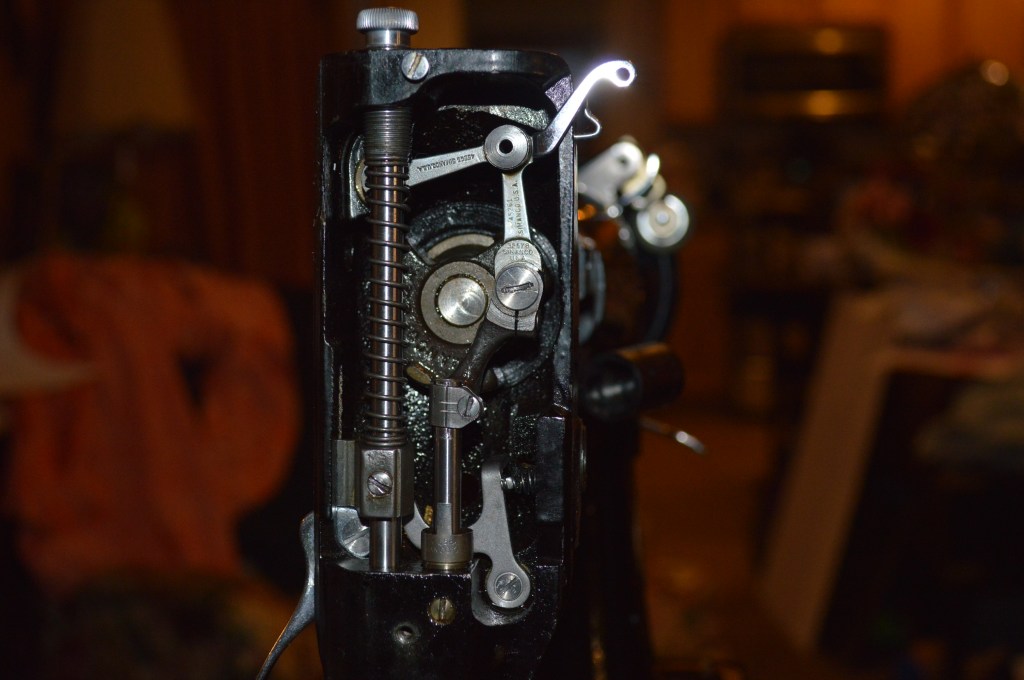

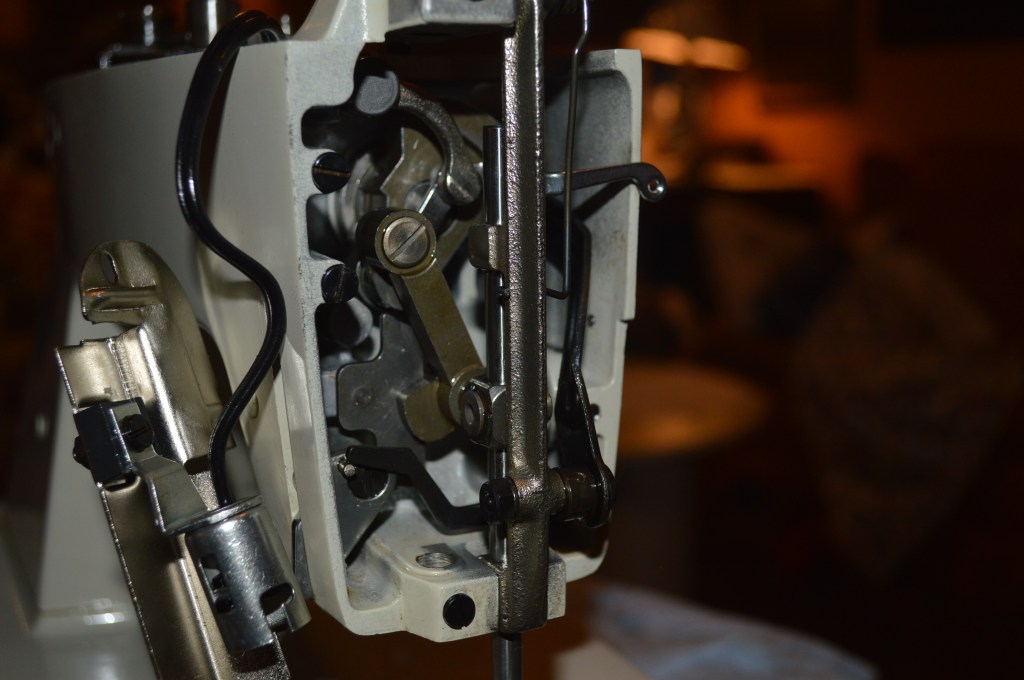

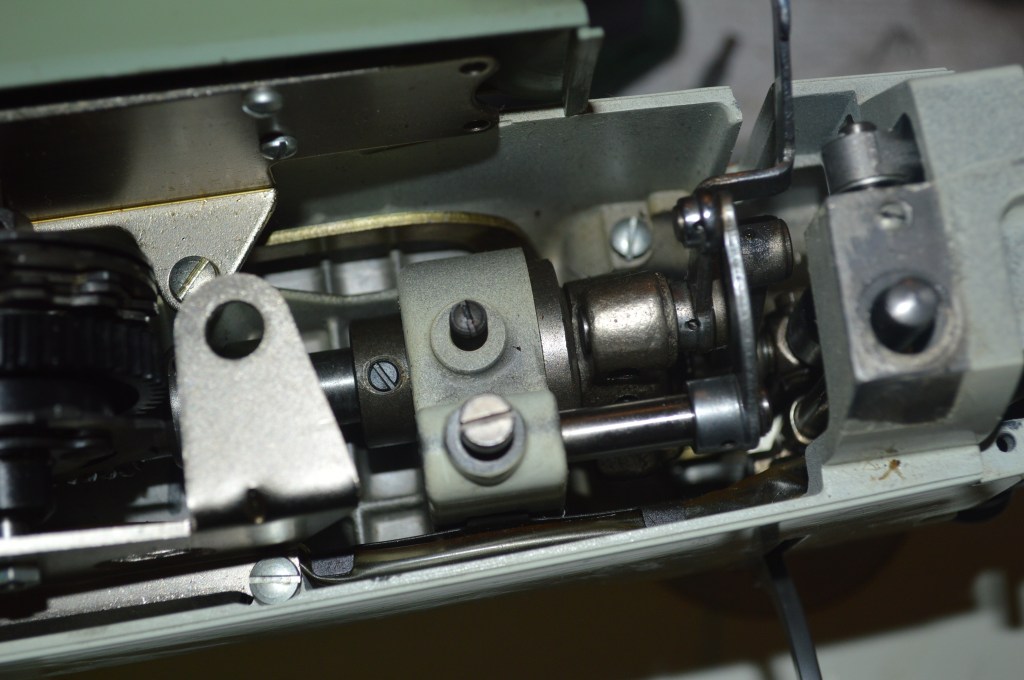

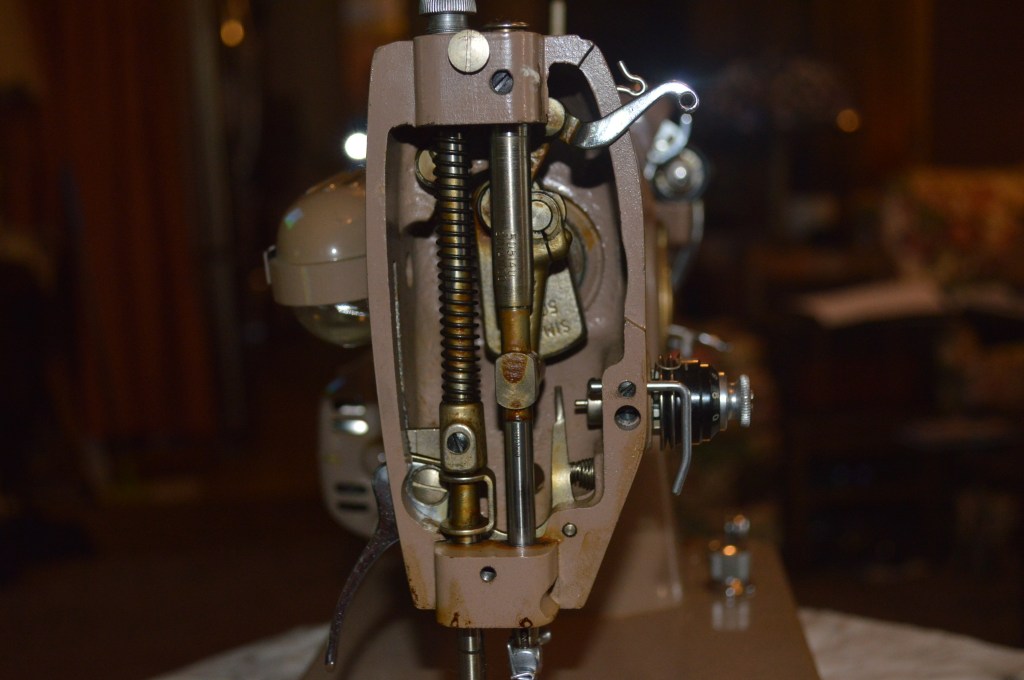

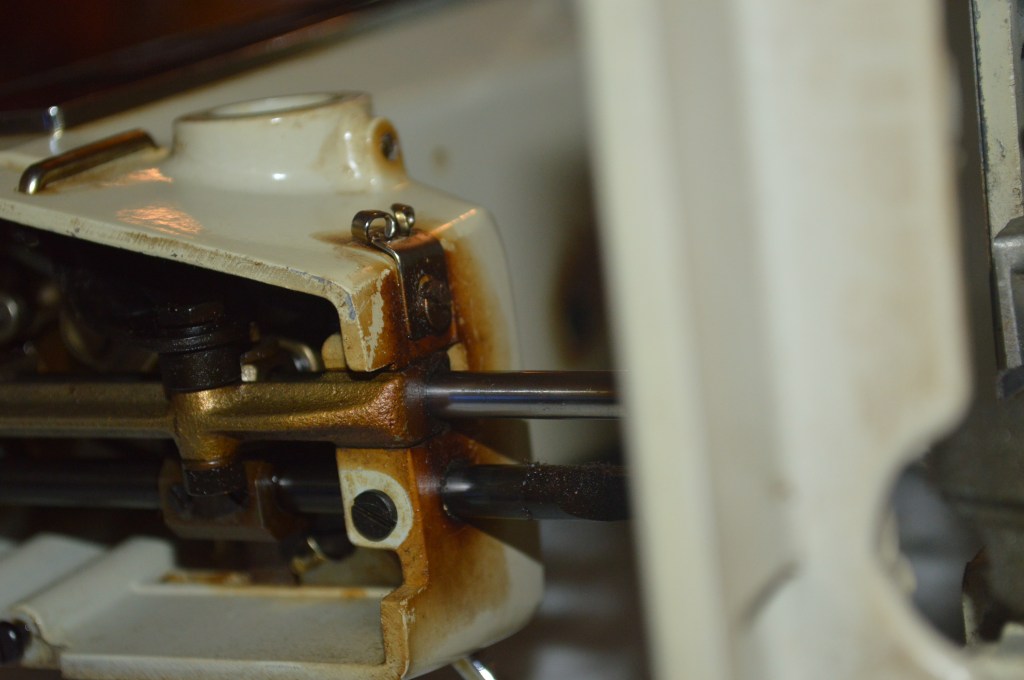

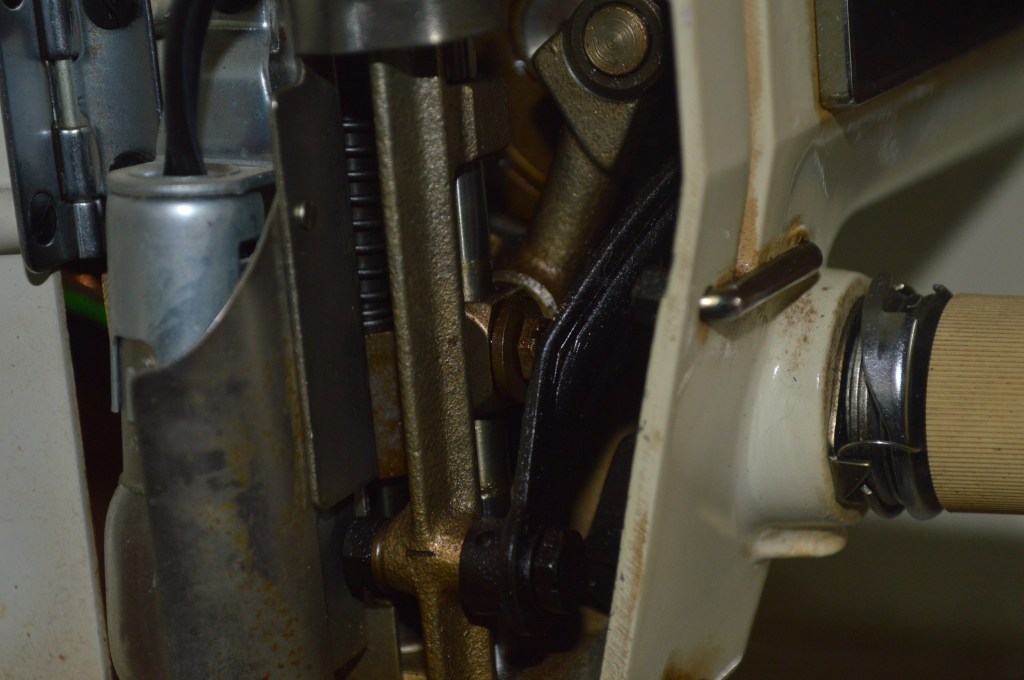

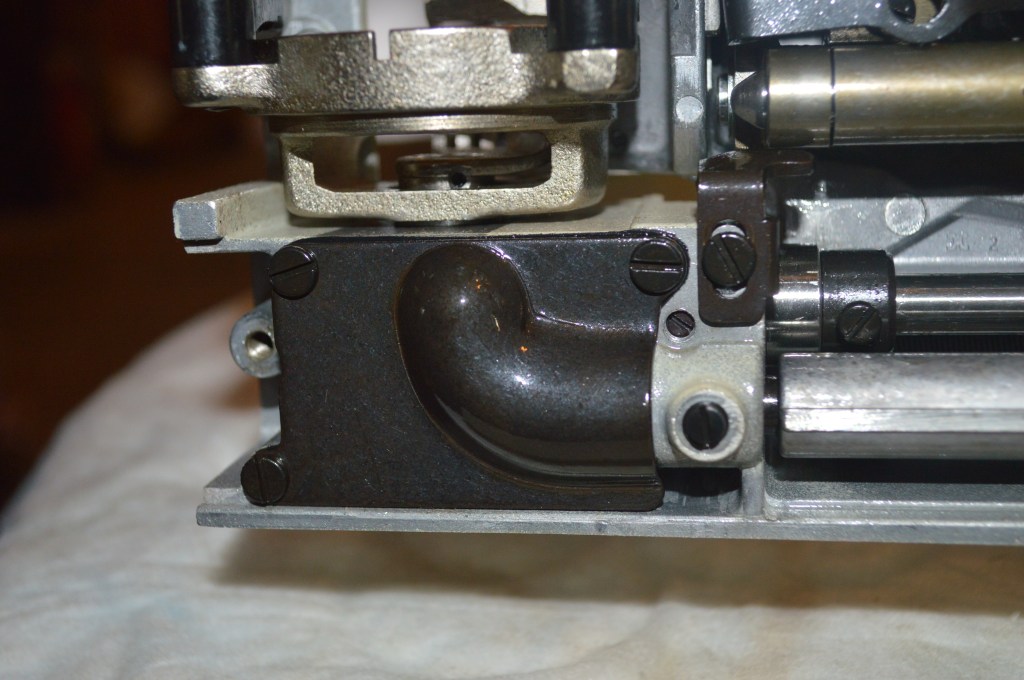

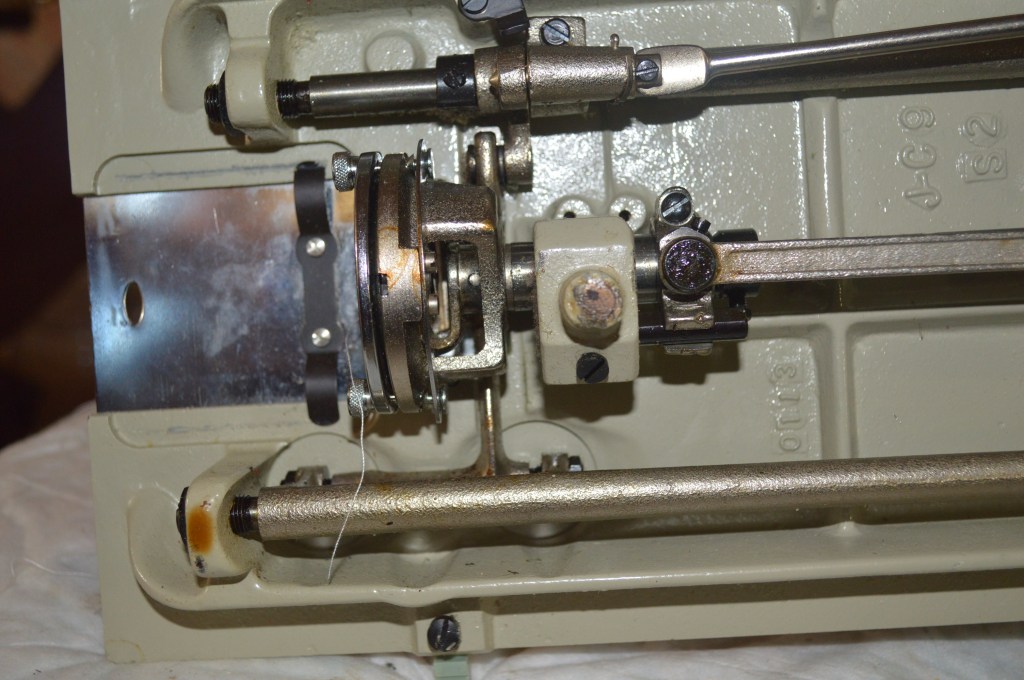

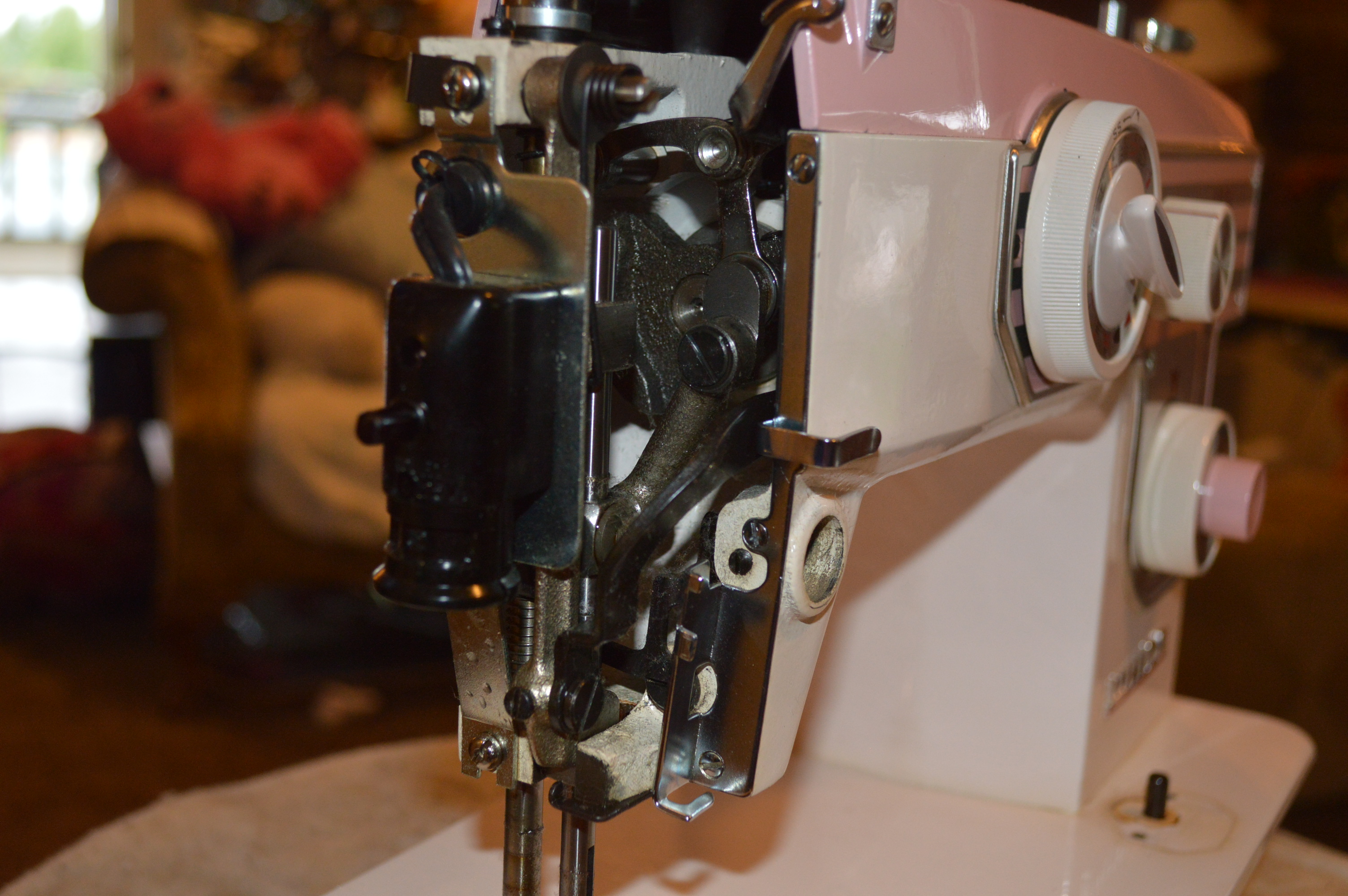

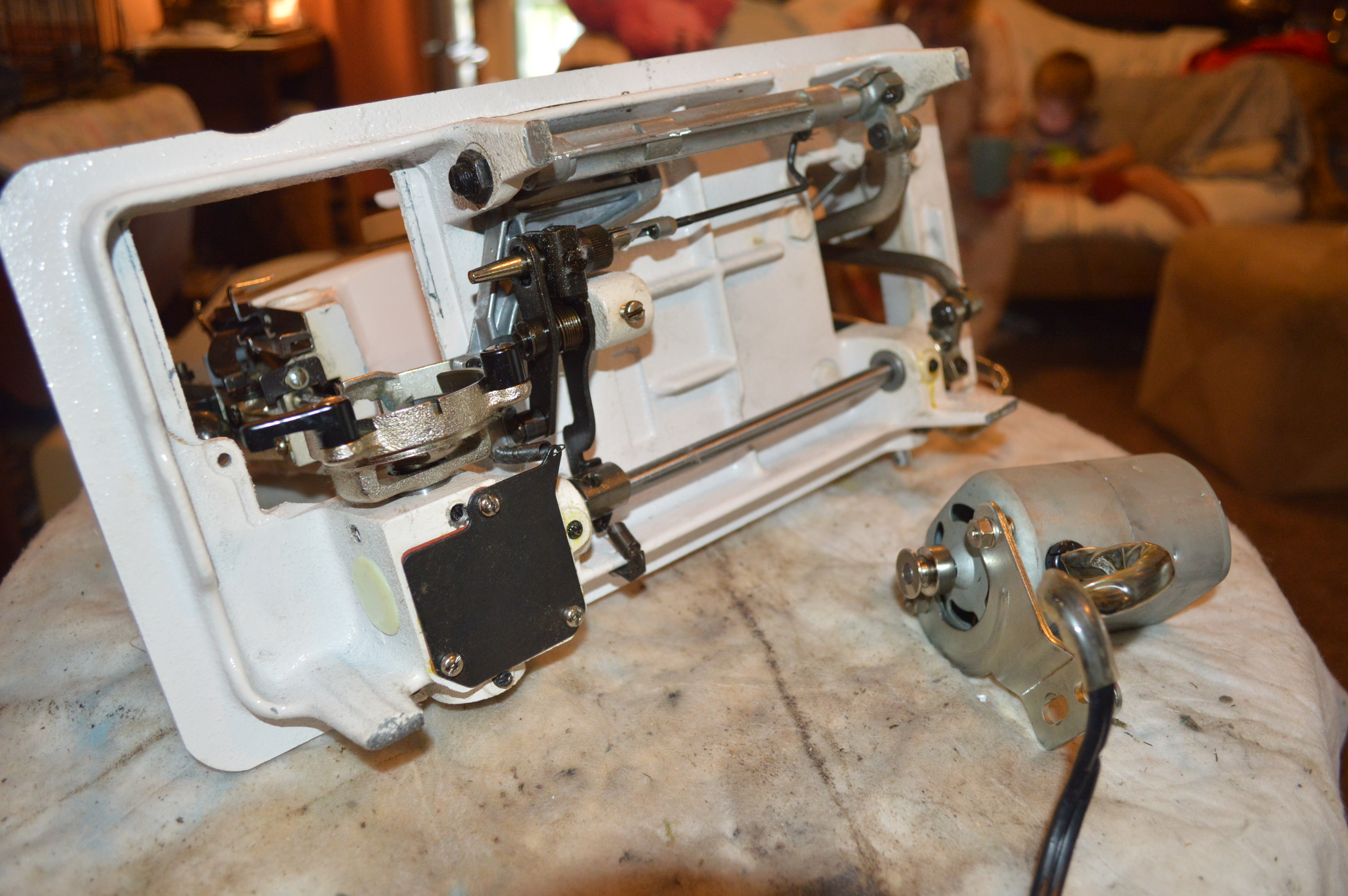

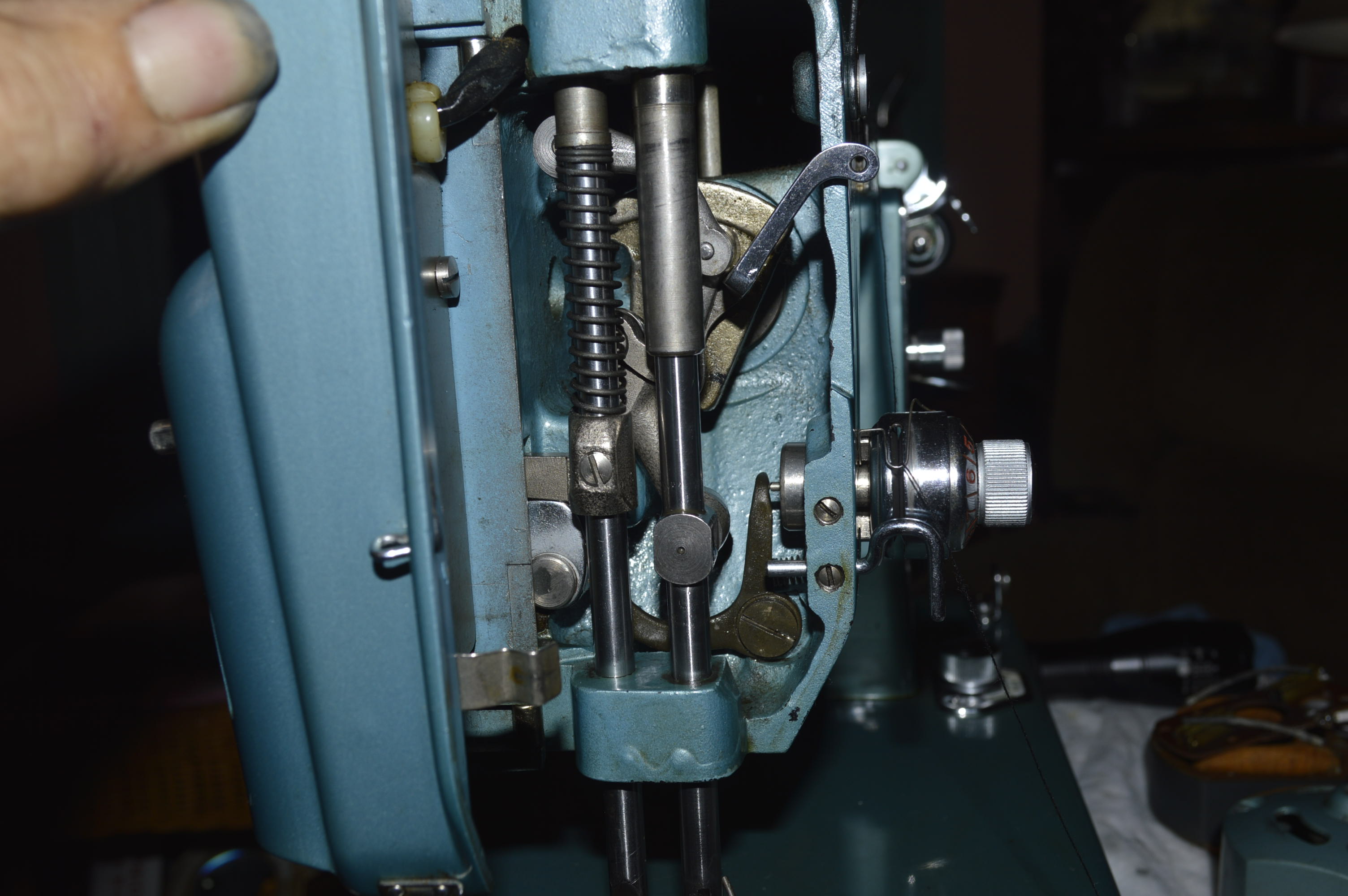

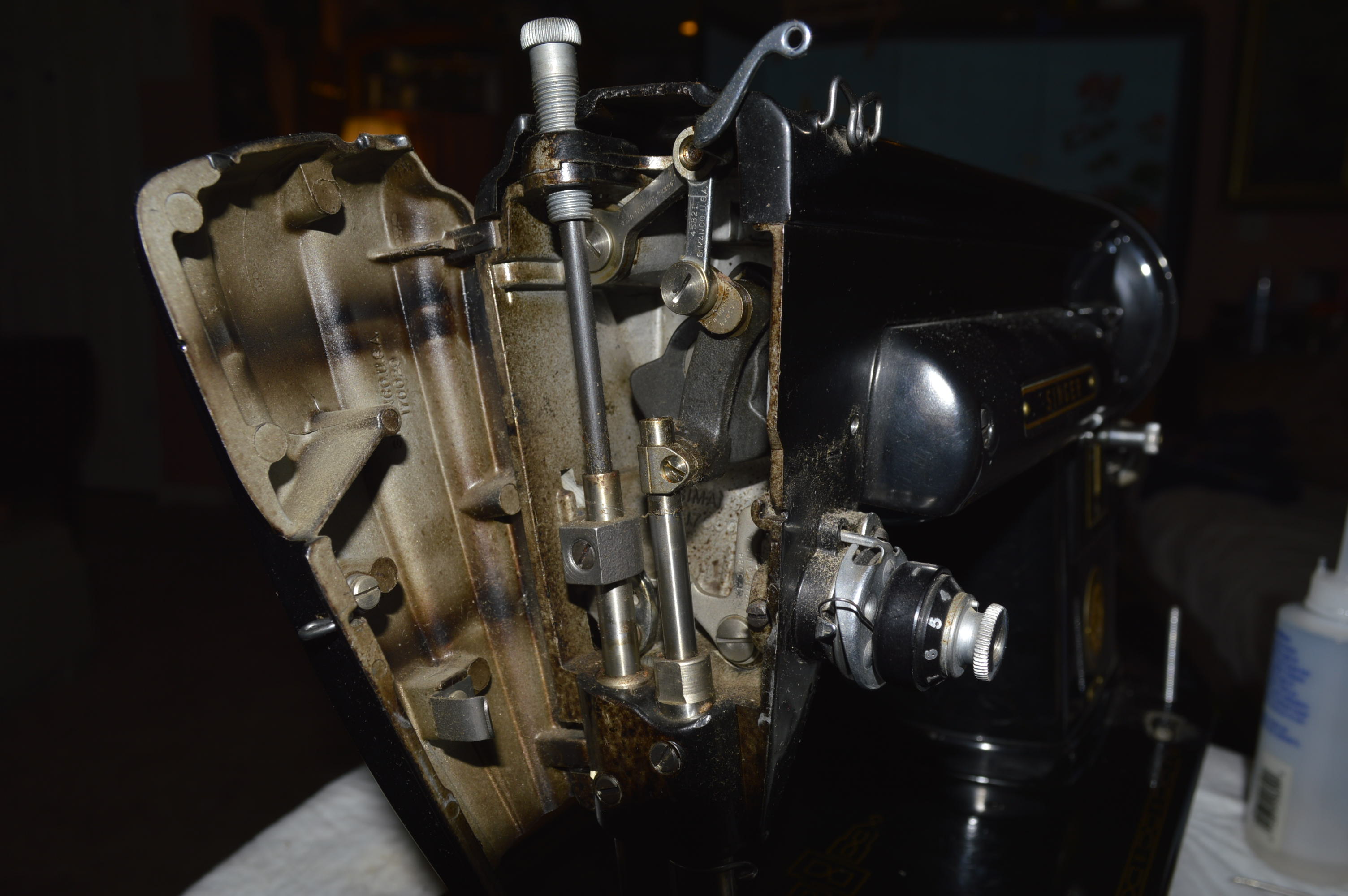

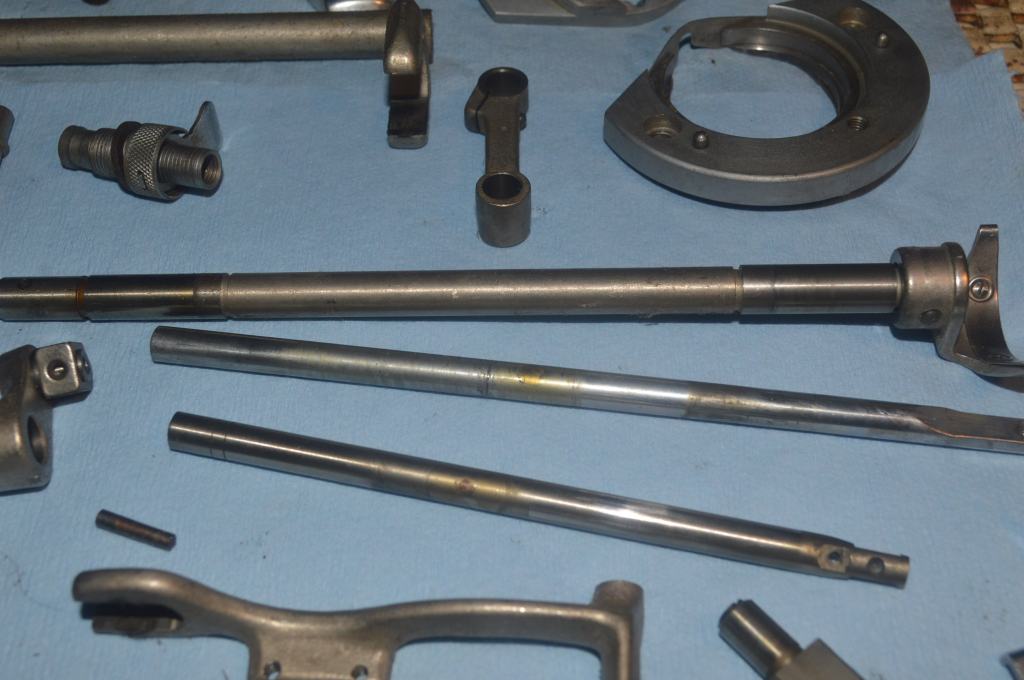

All of the assemblies in the sewing machine’s needle bar area are removed.

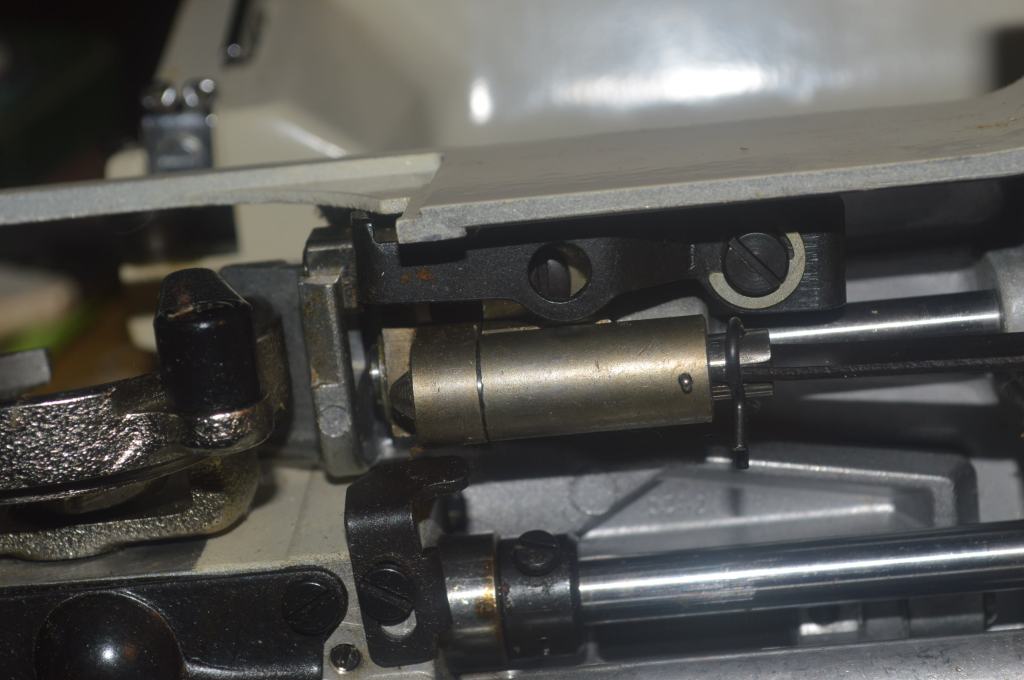

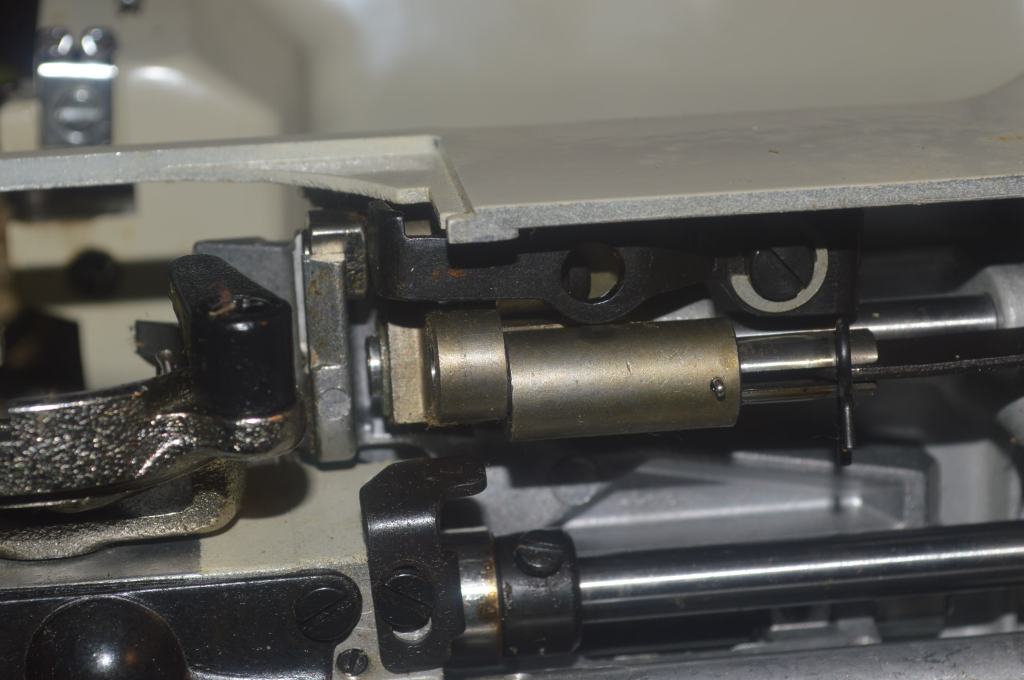

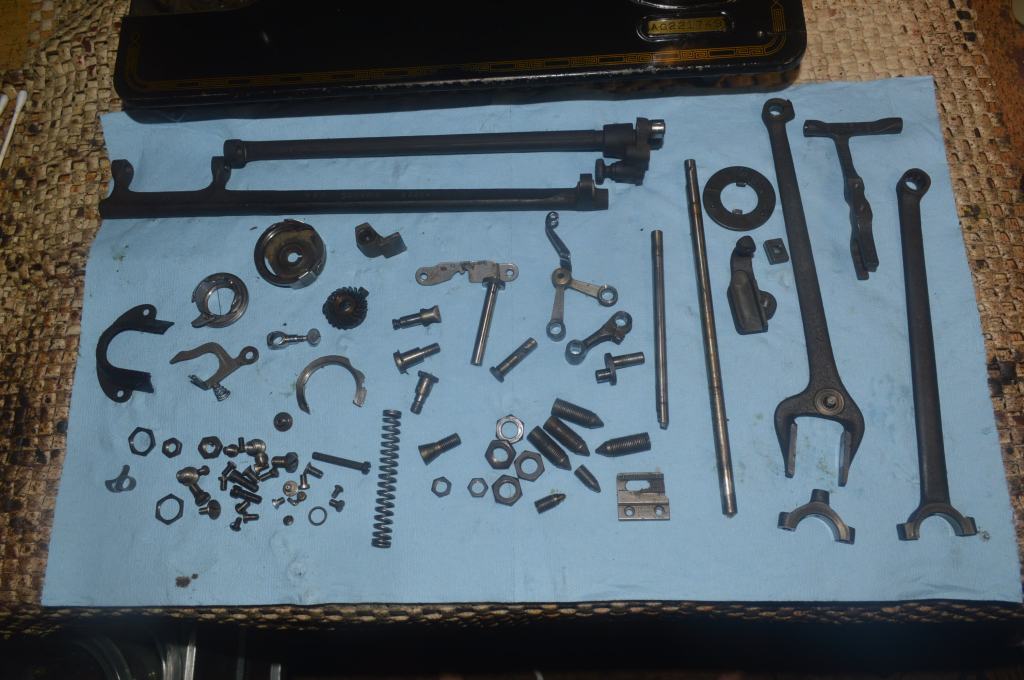

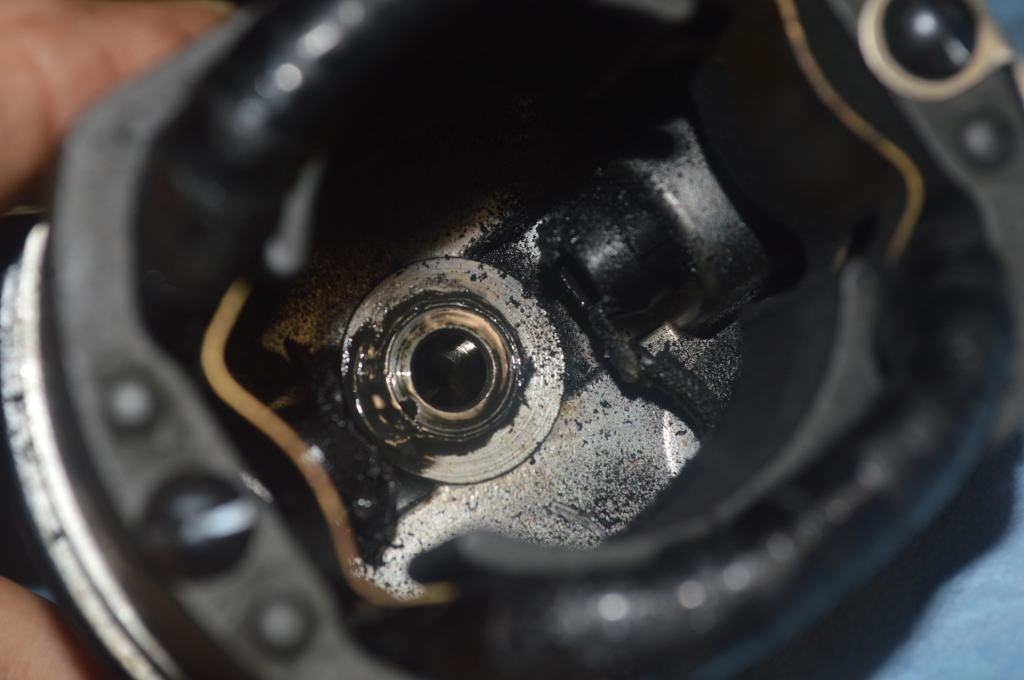

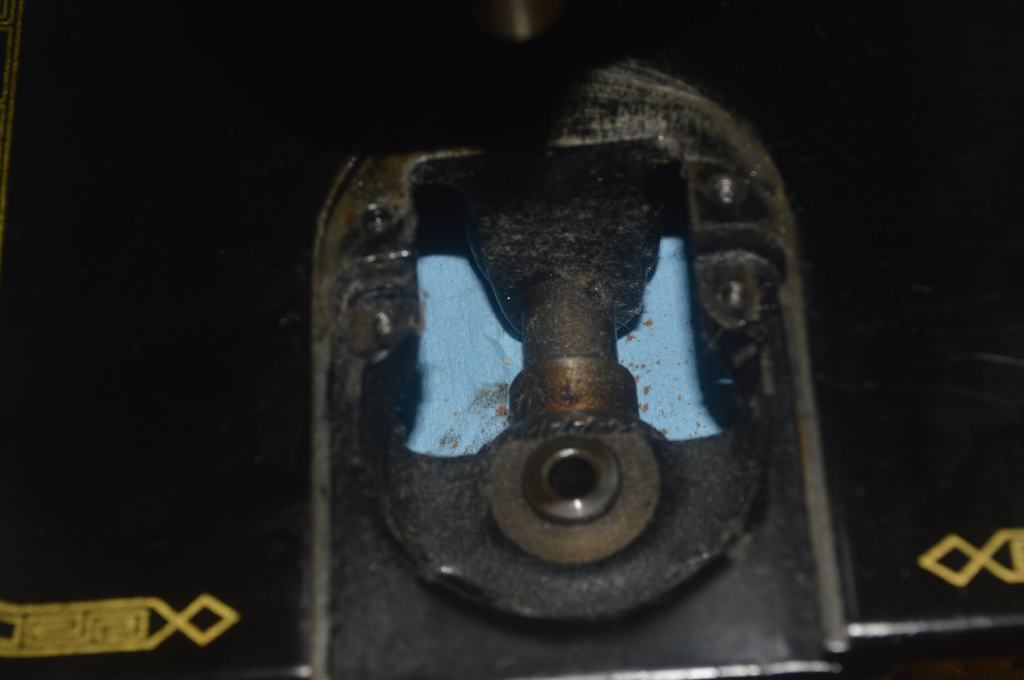

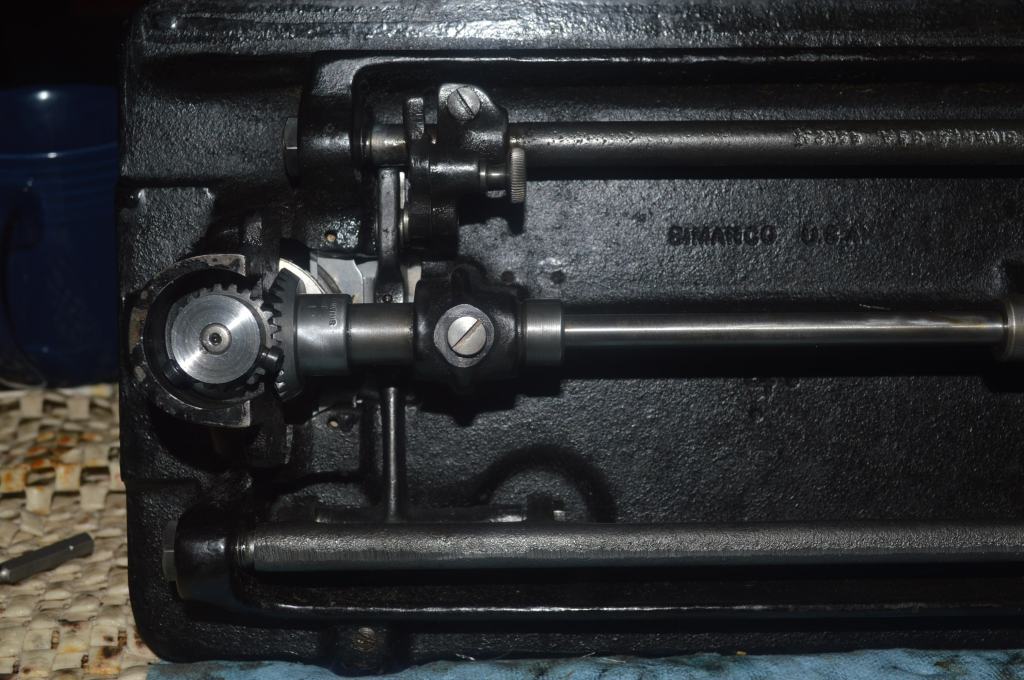

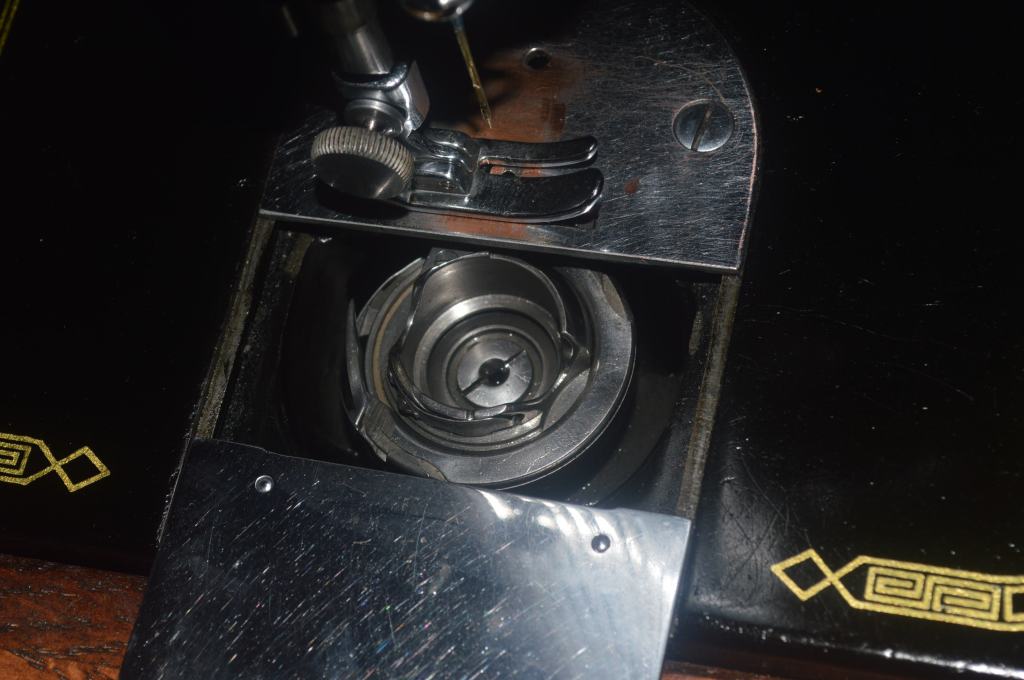

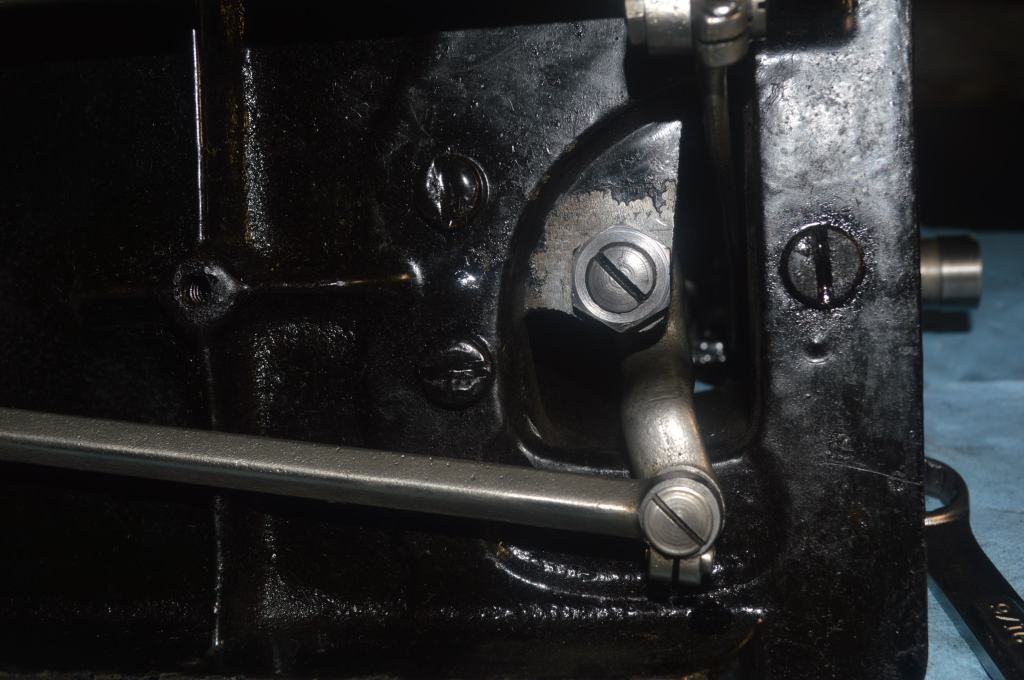

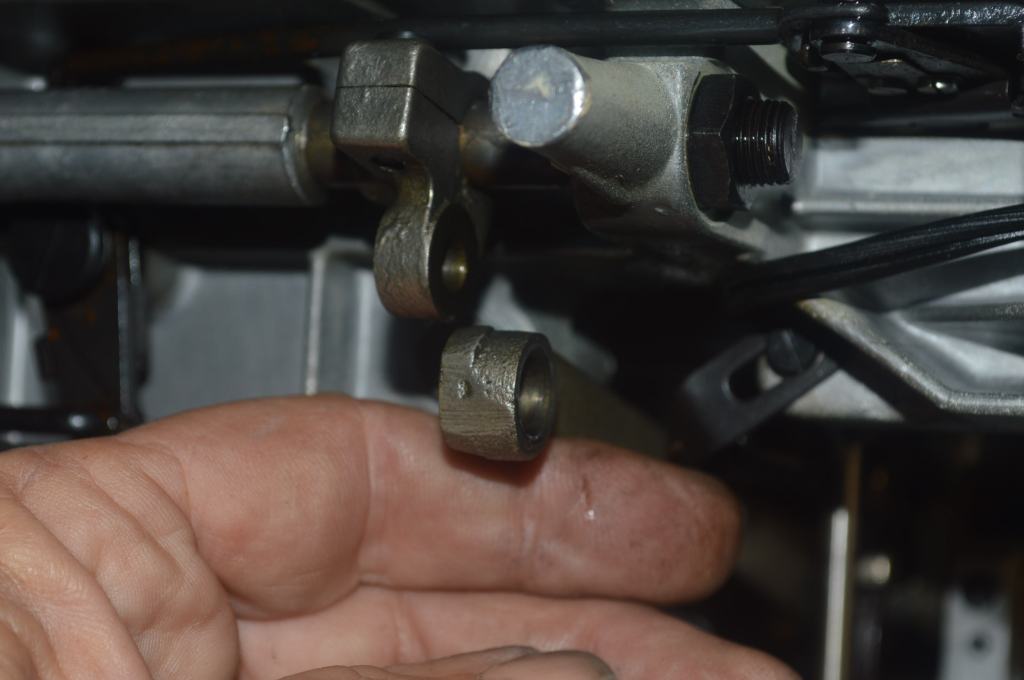

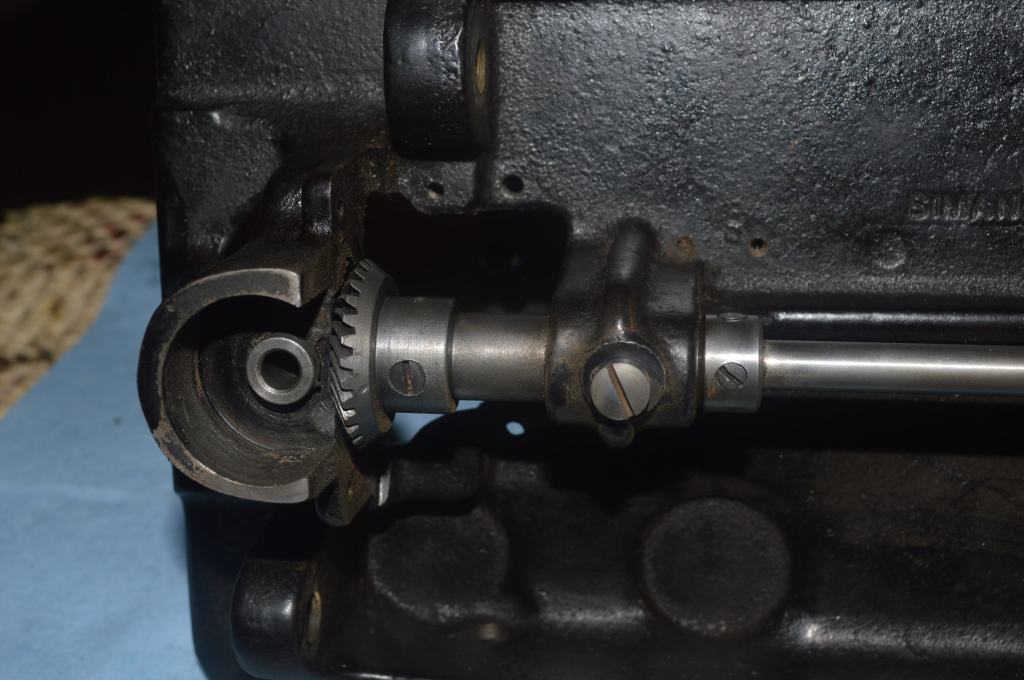

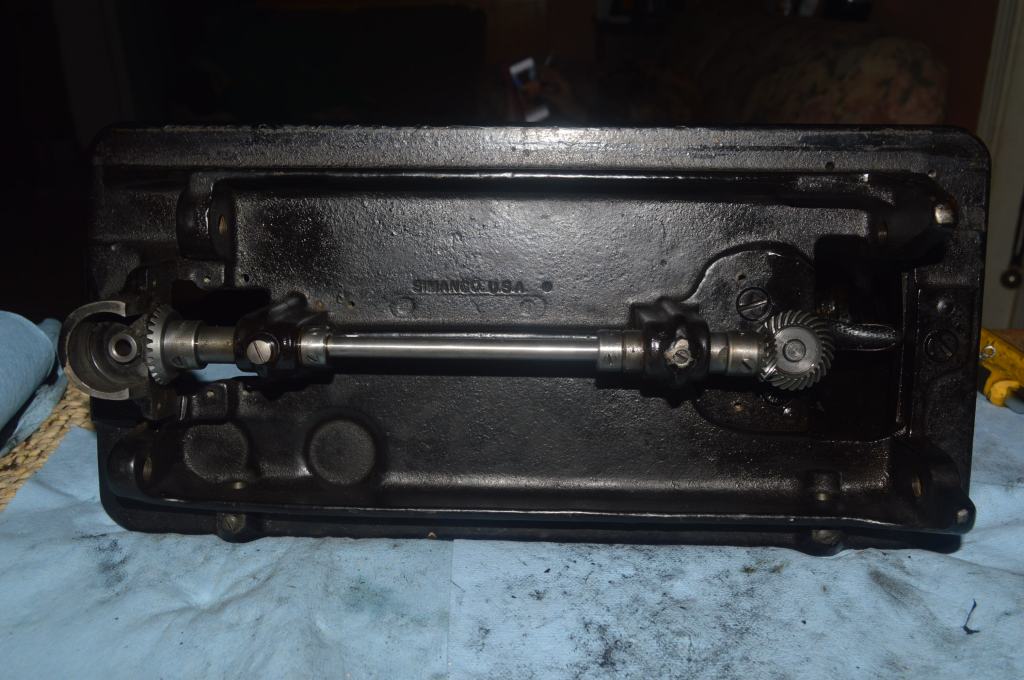

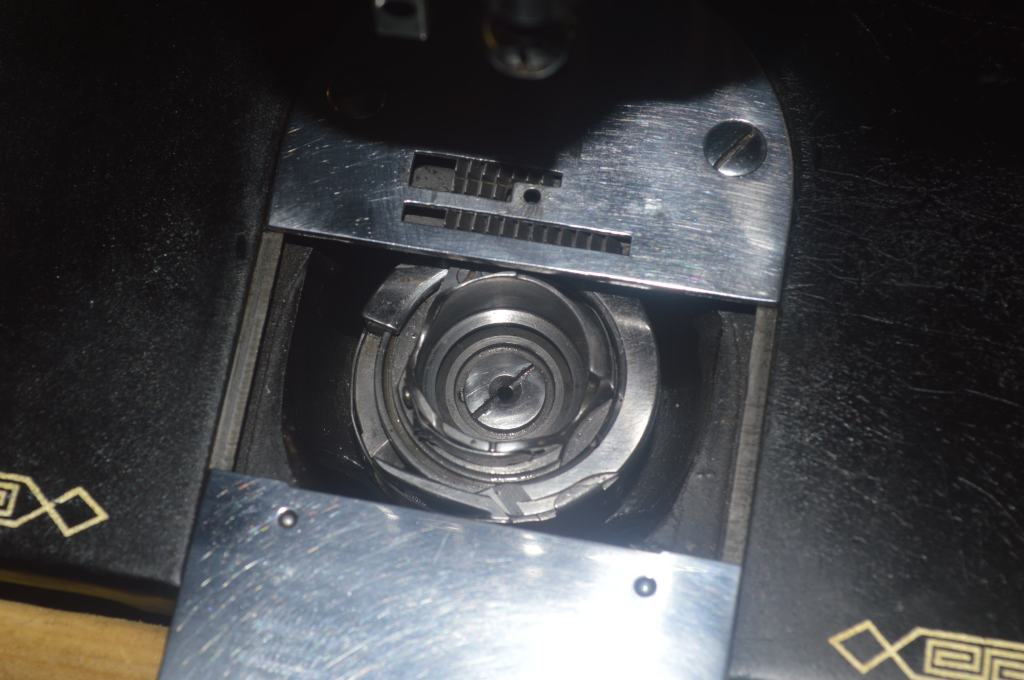

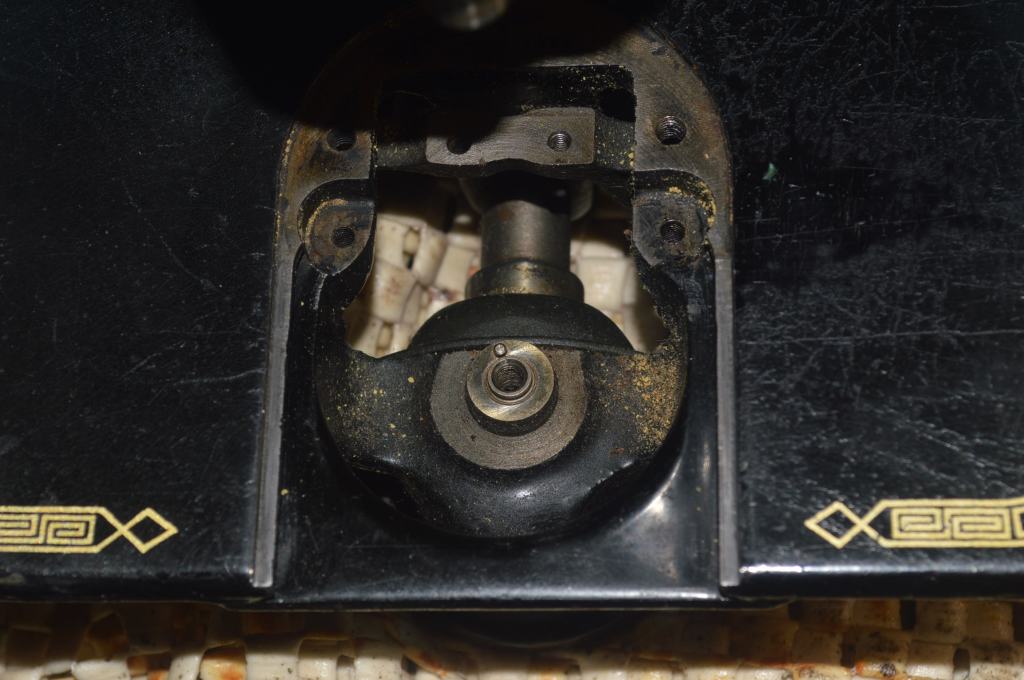

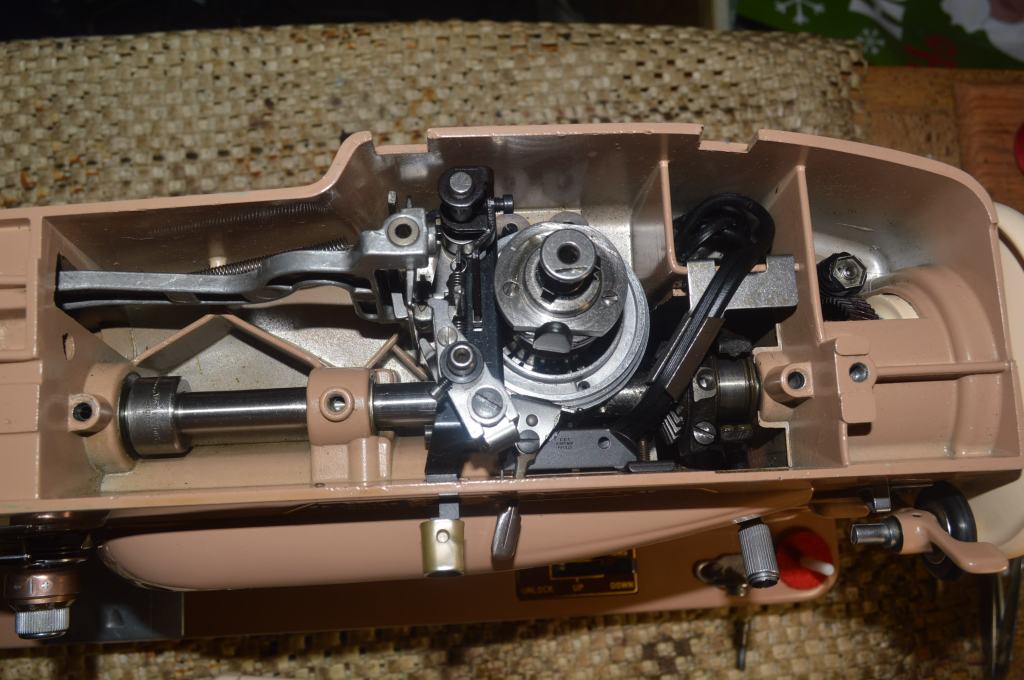

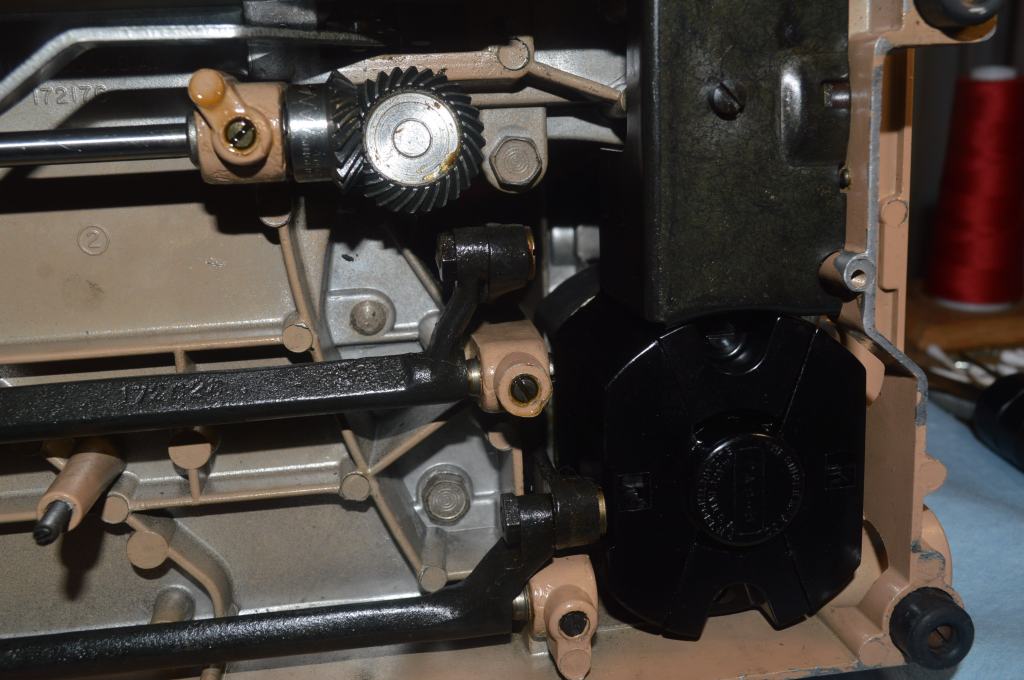

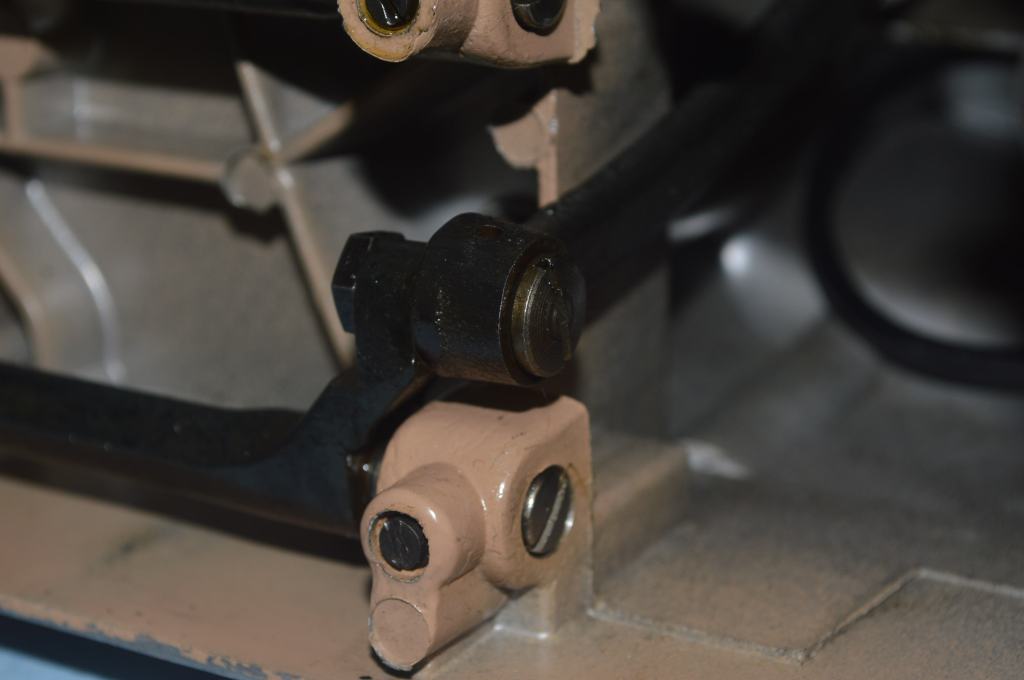

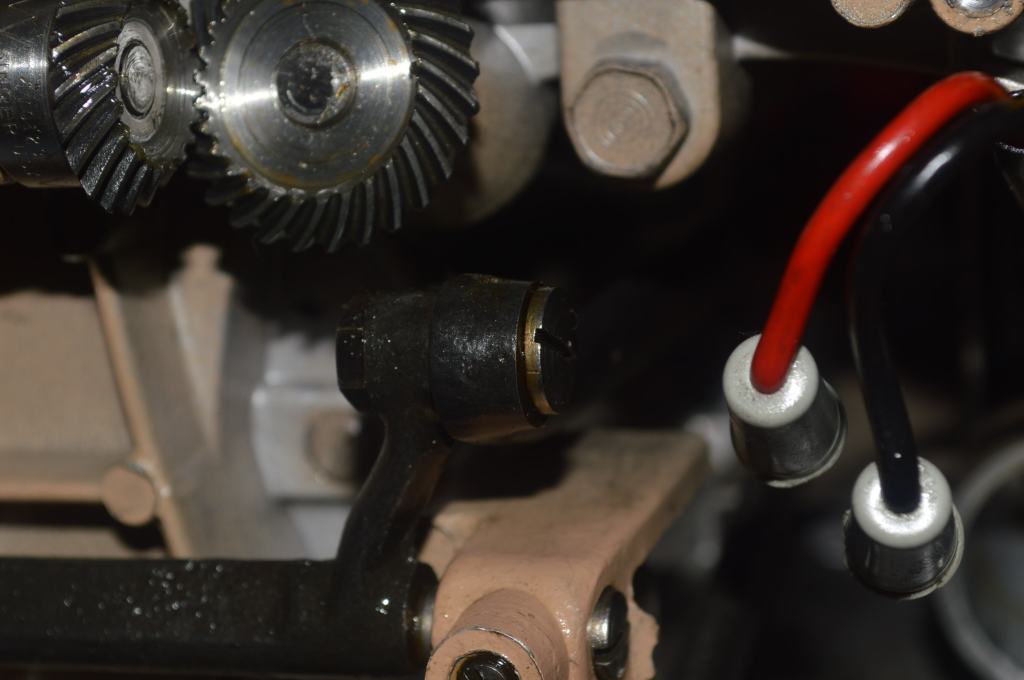

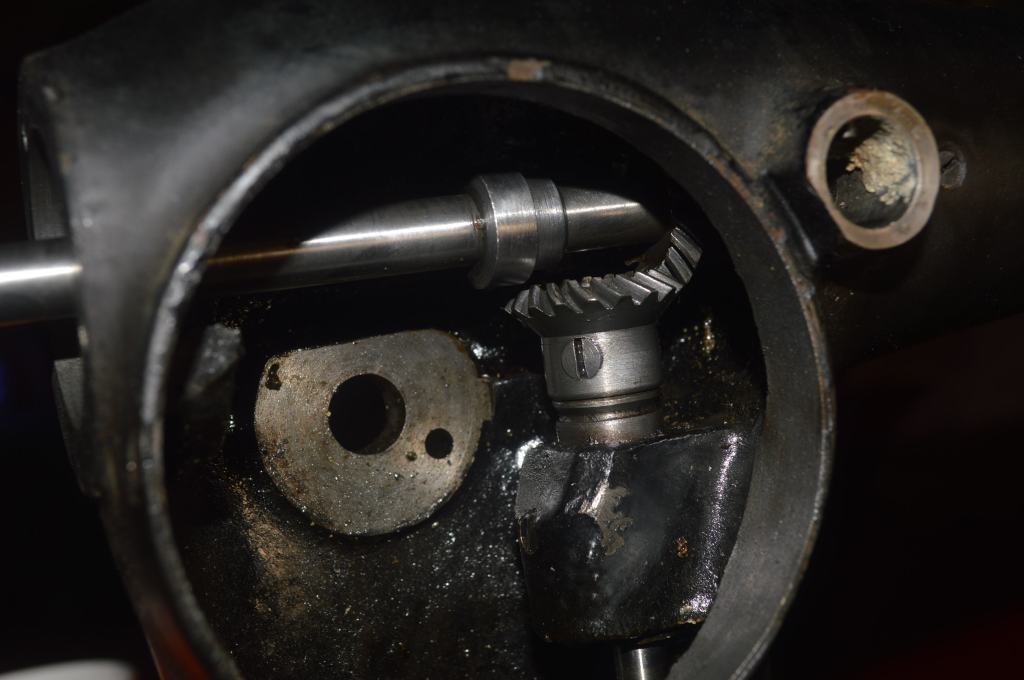

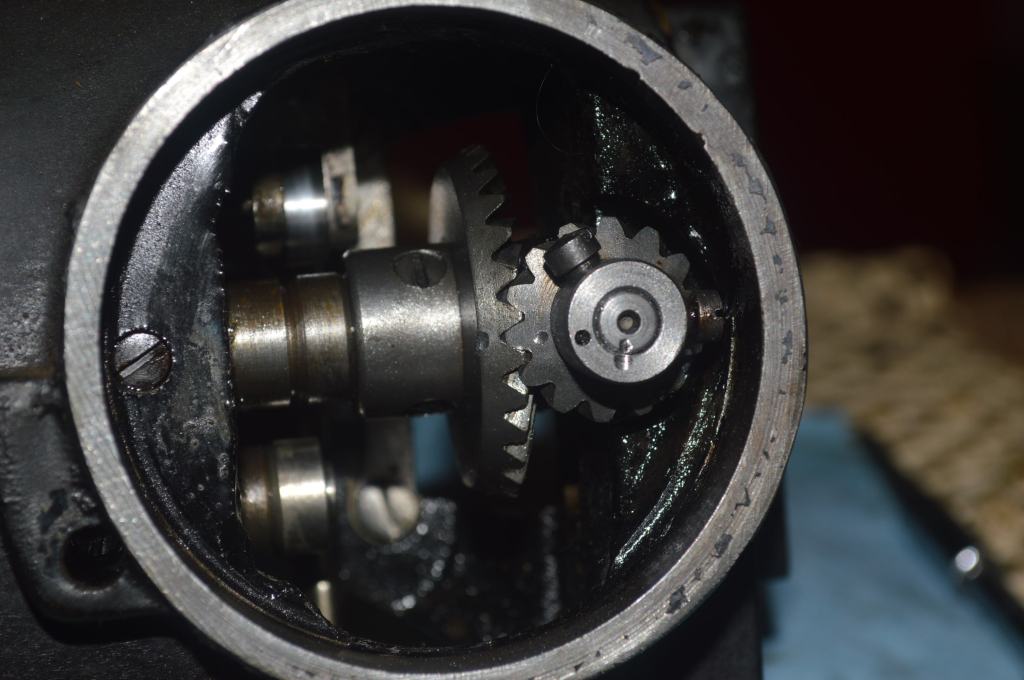

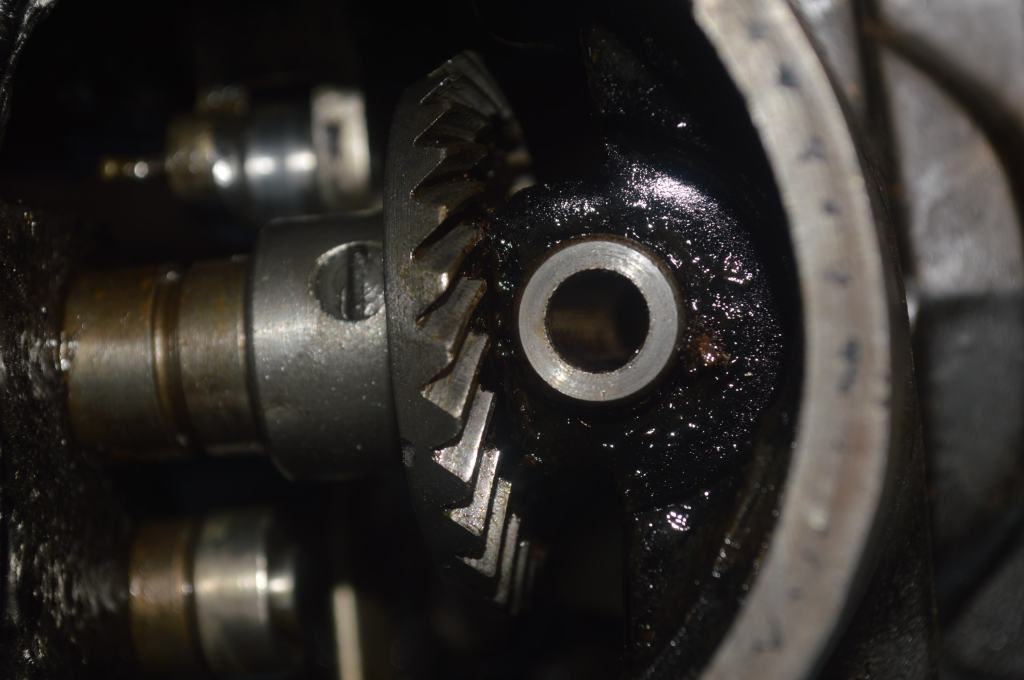

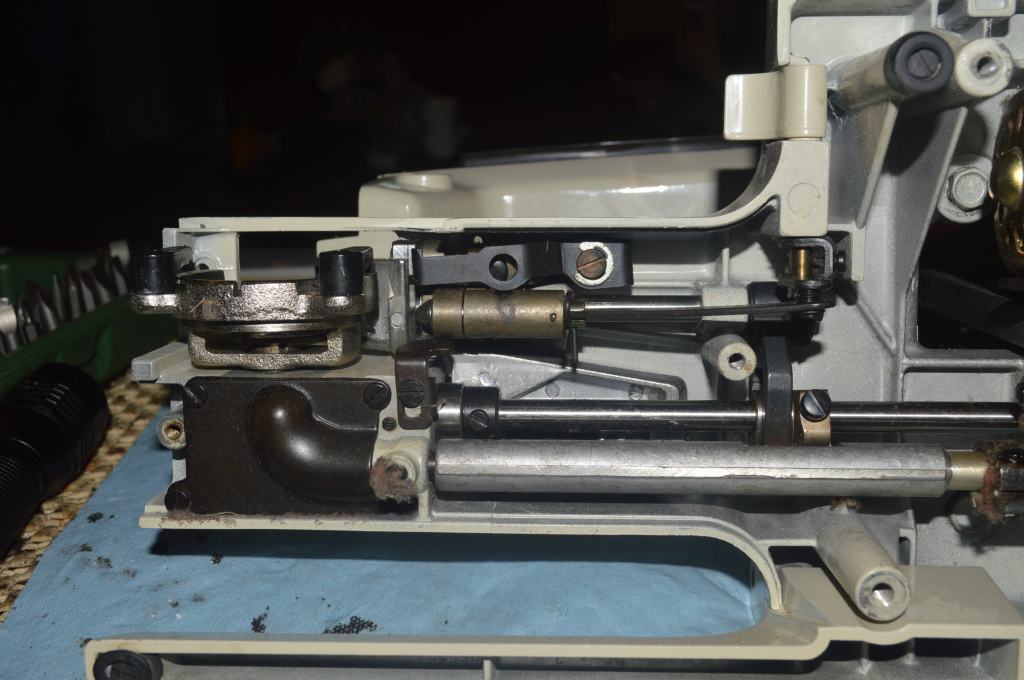

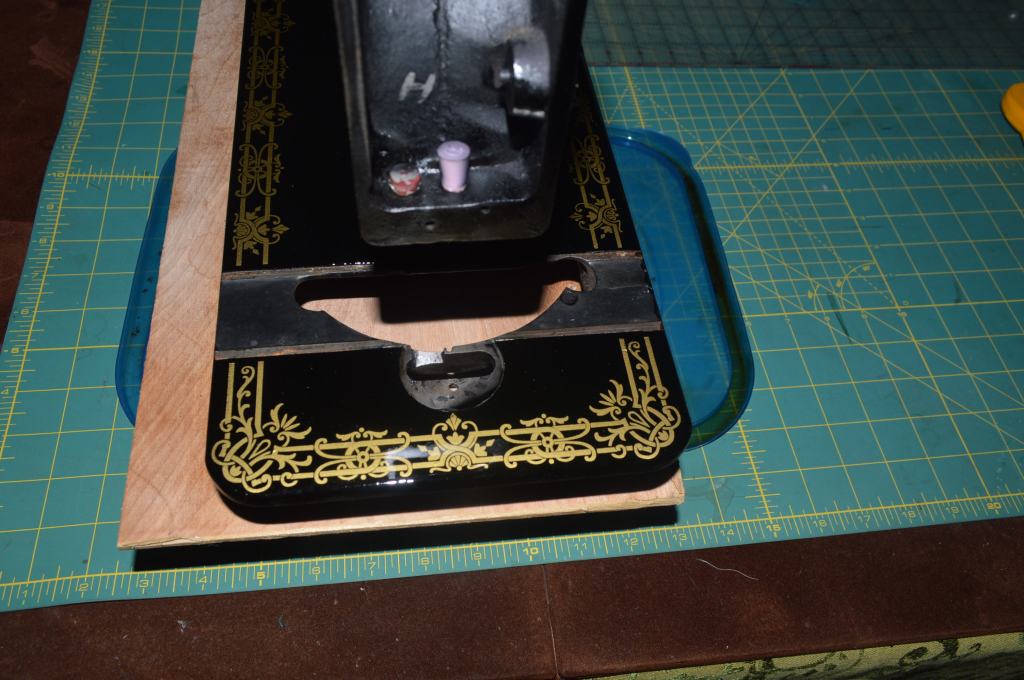

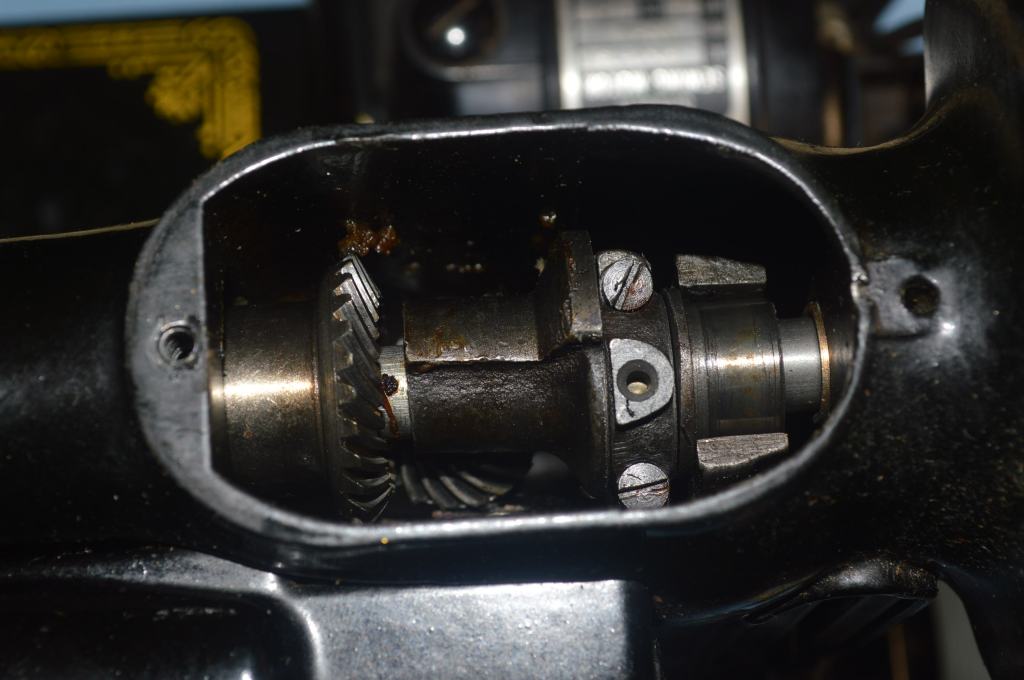

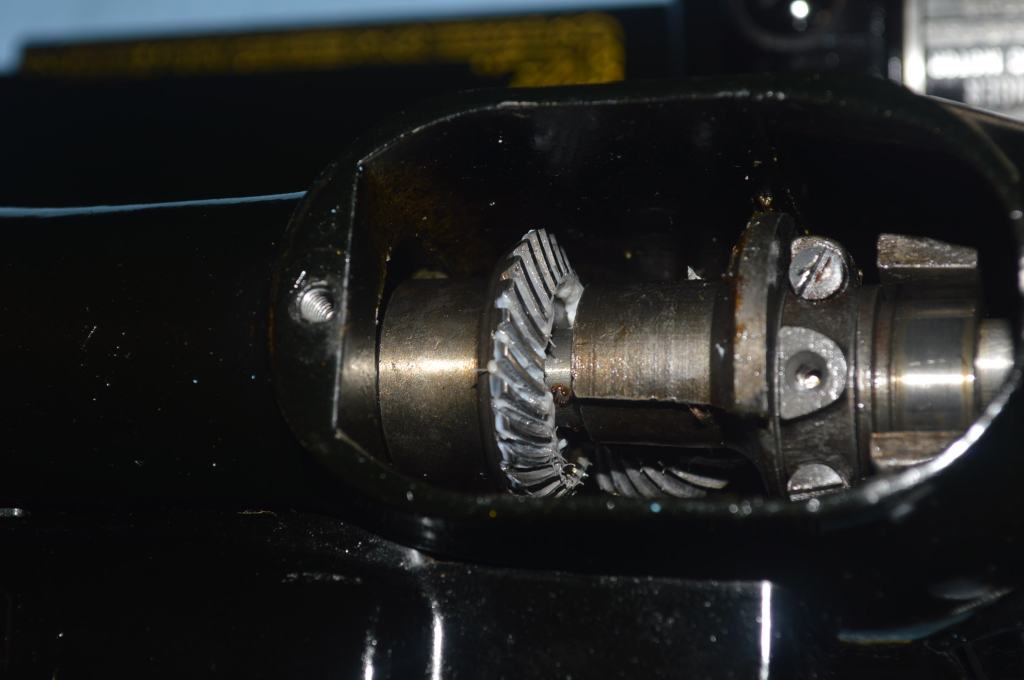

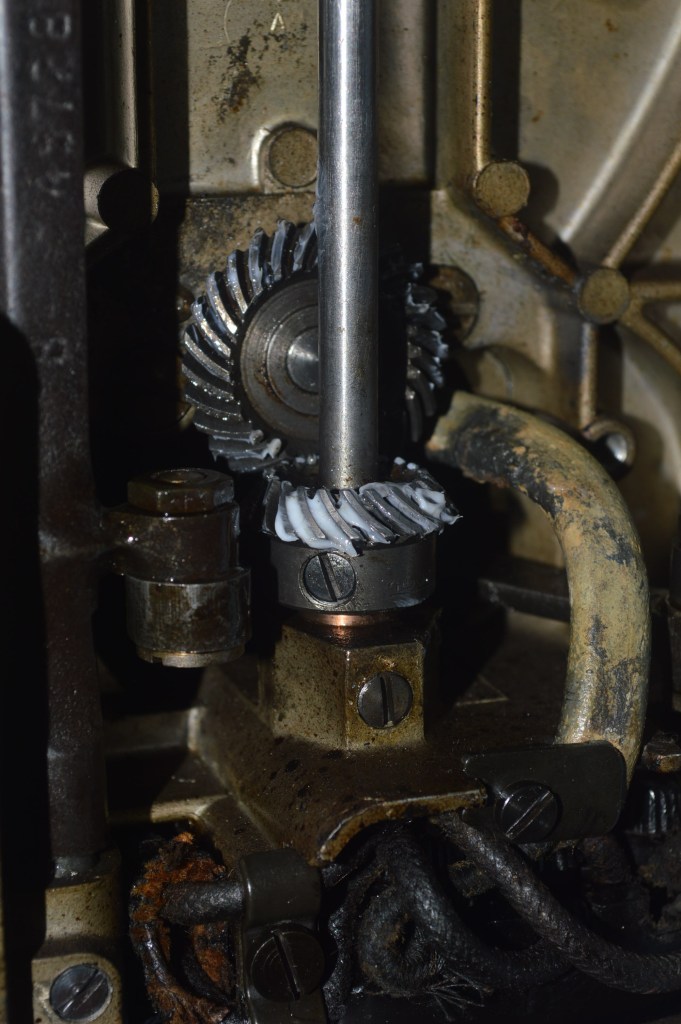

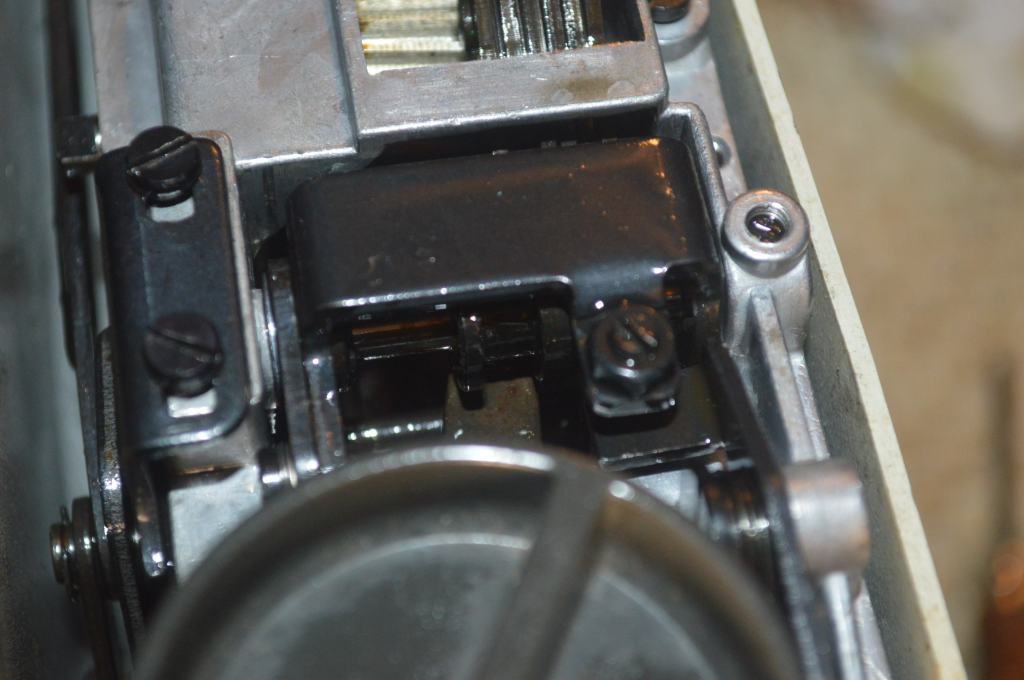

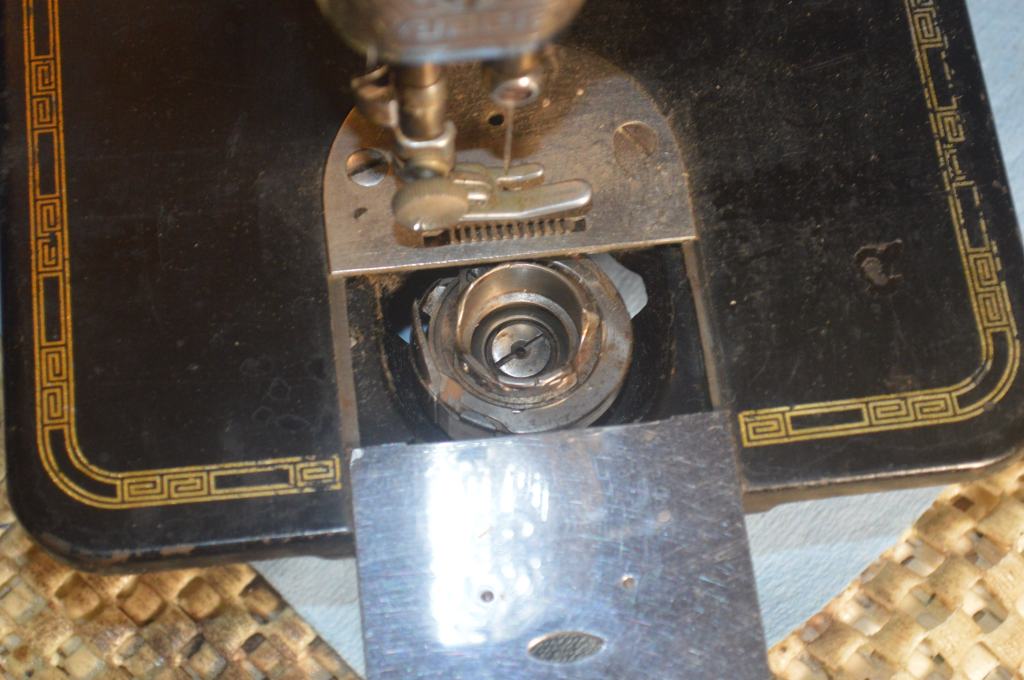

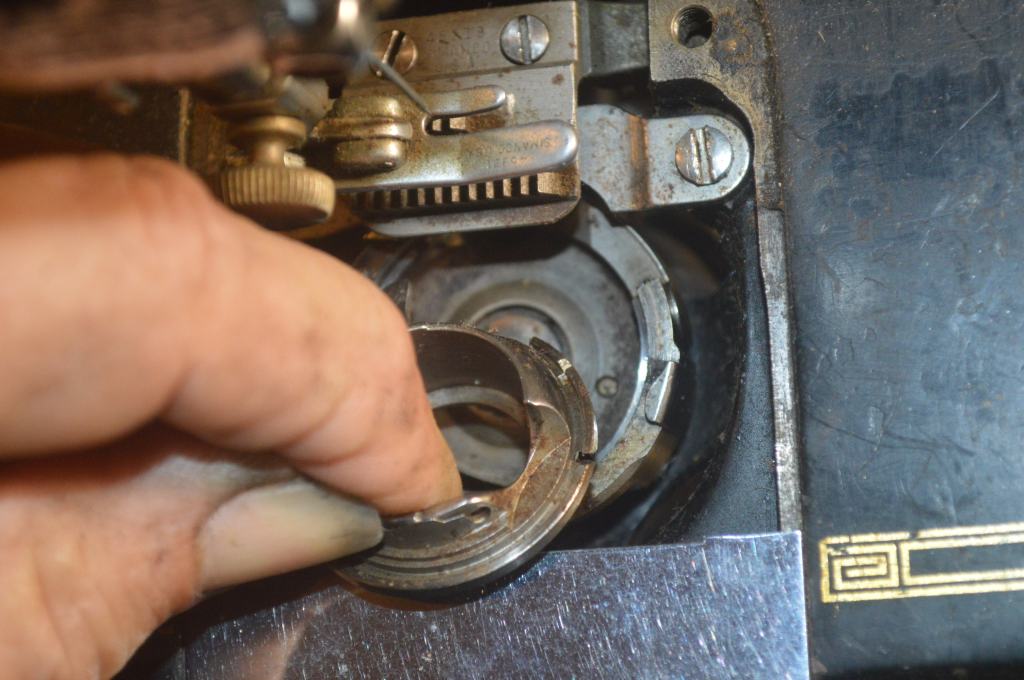

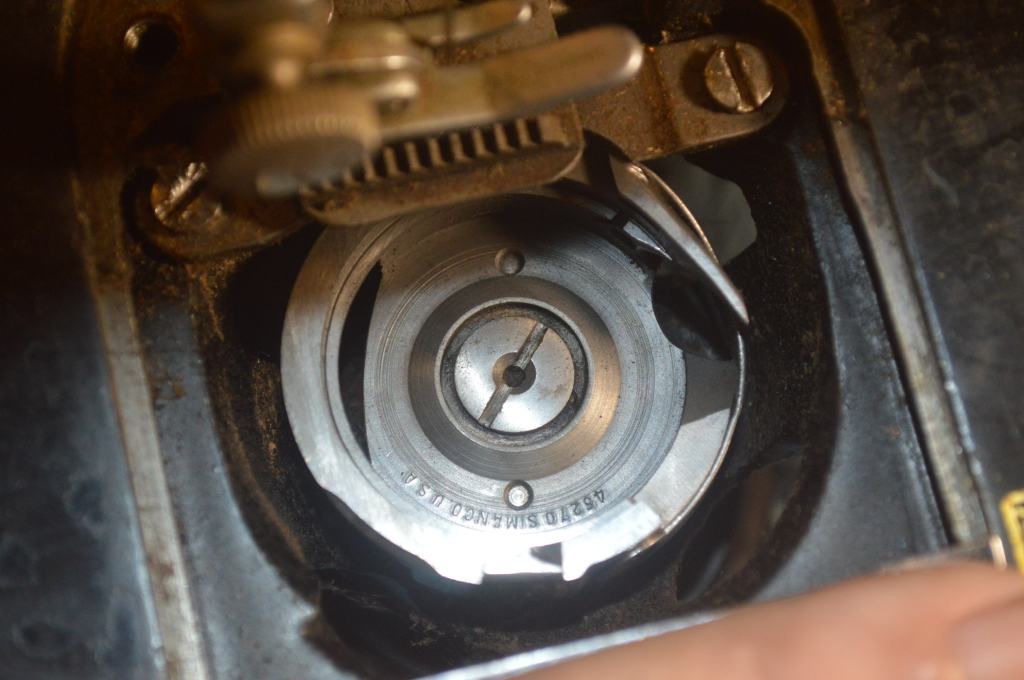

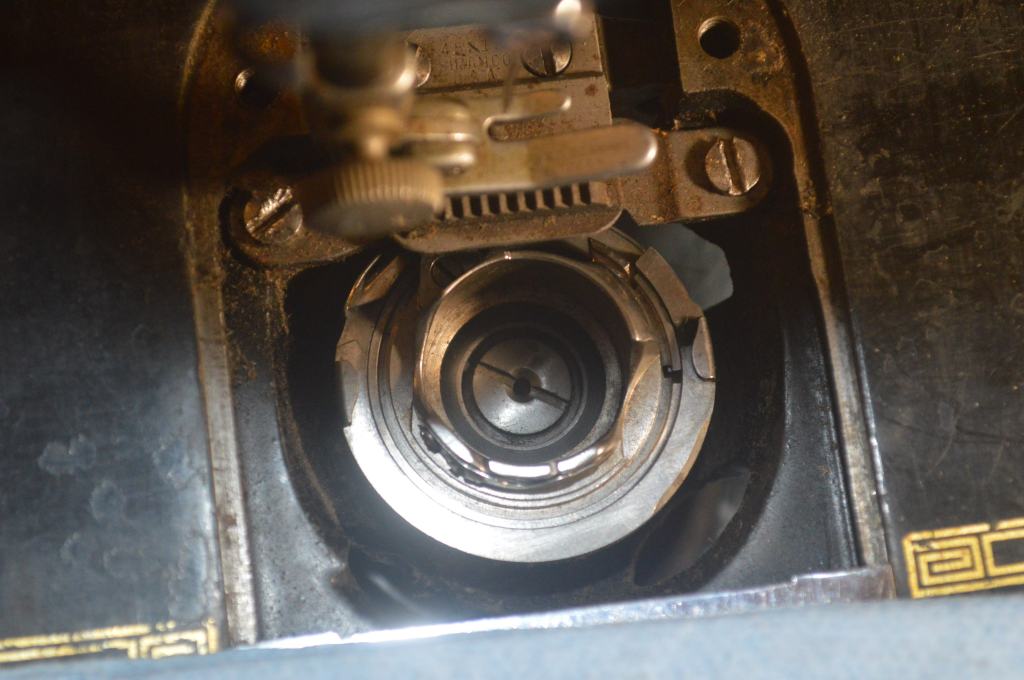

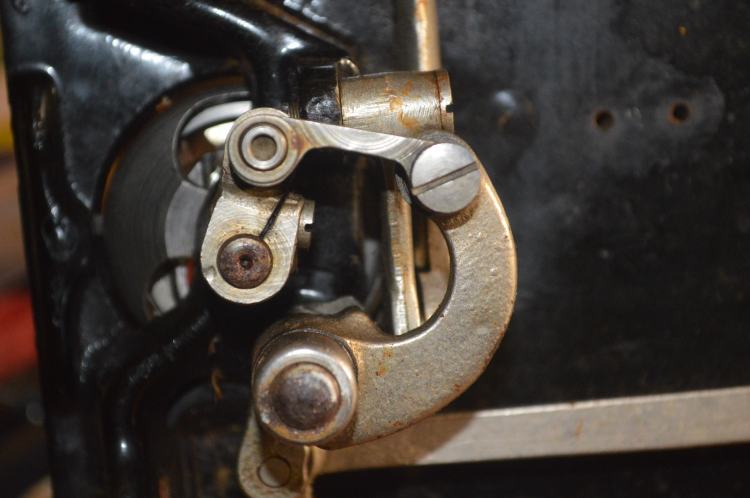

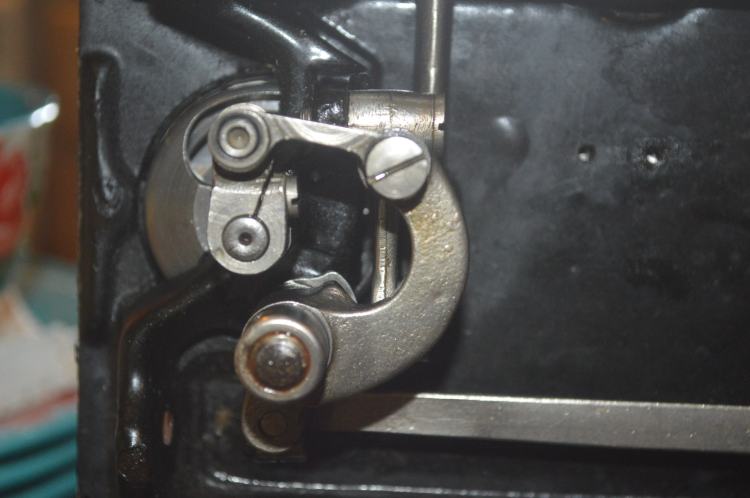

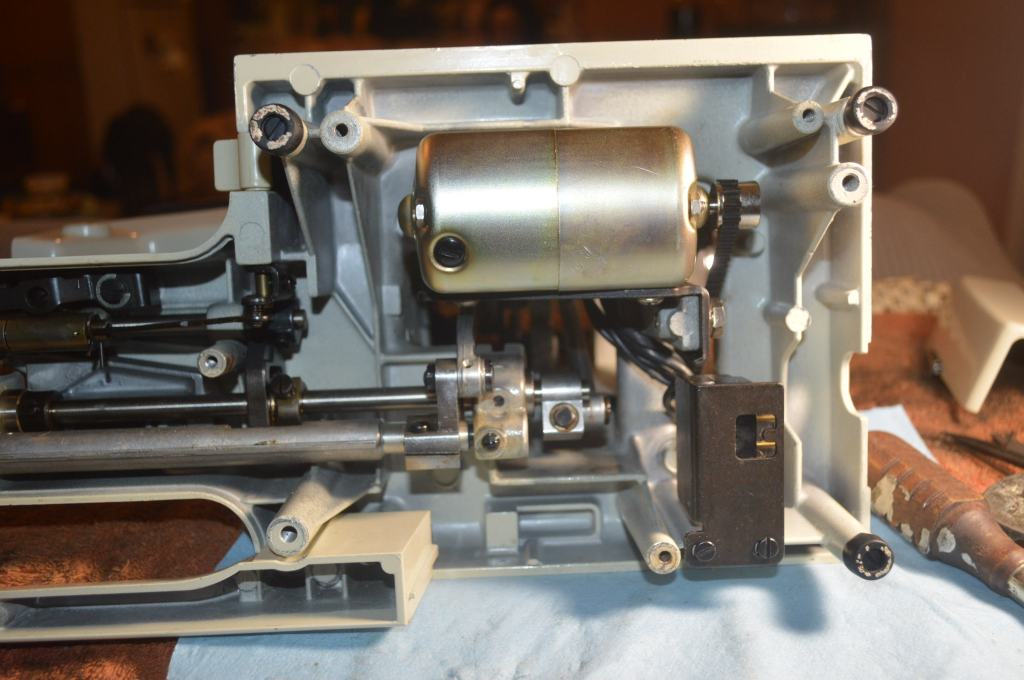

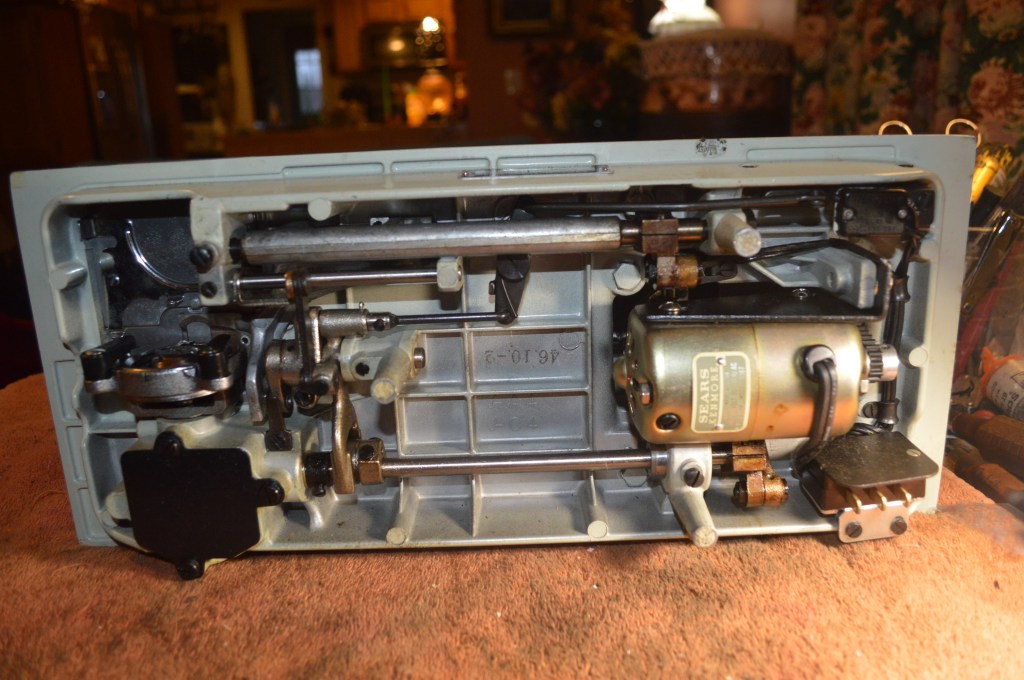

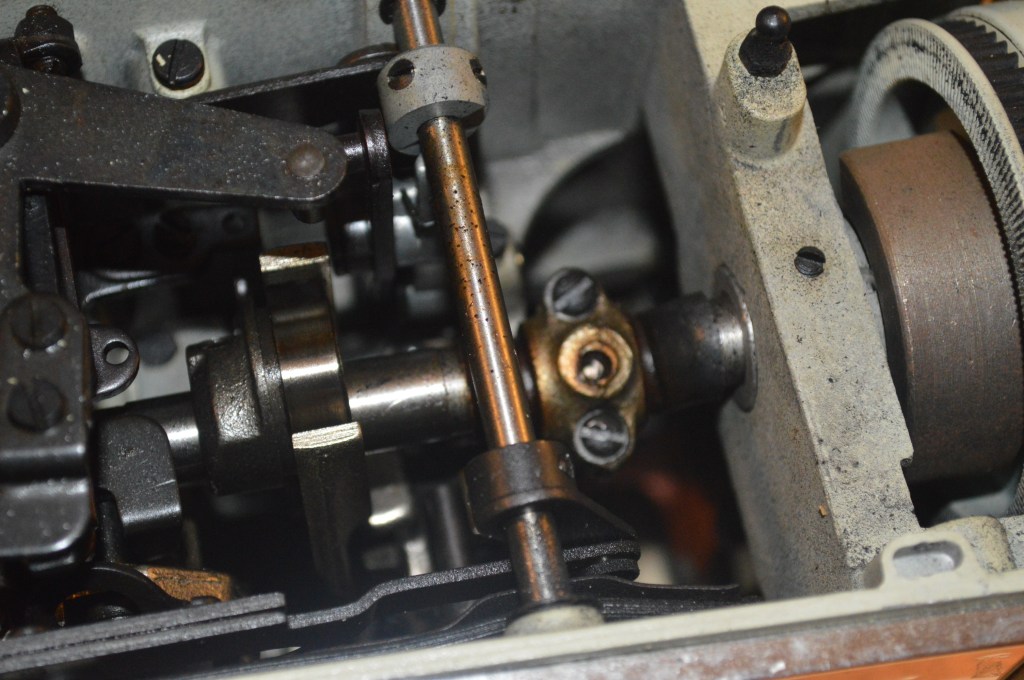

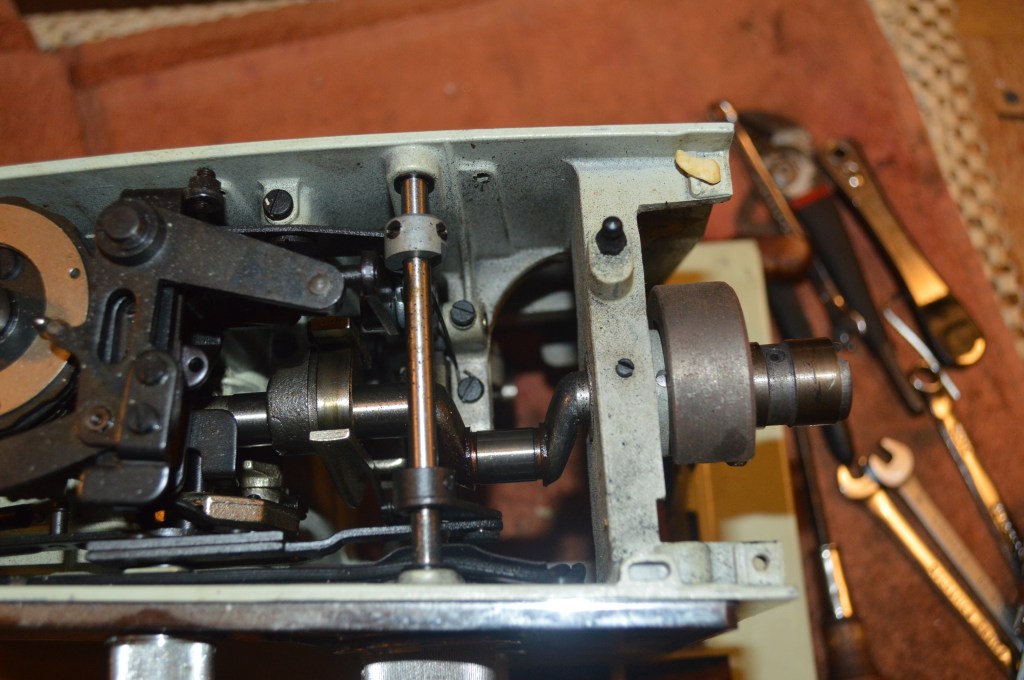

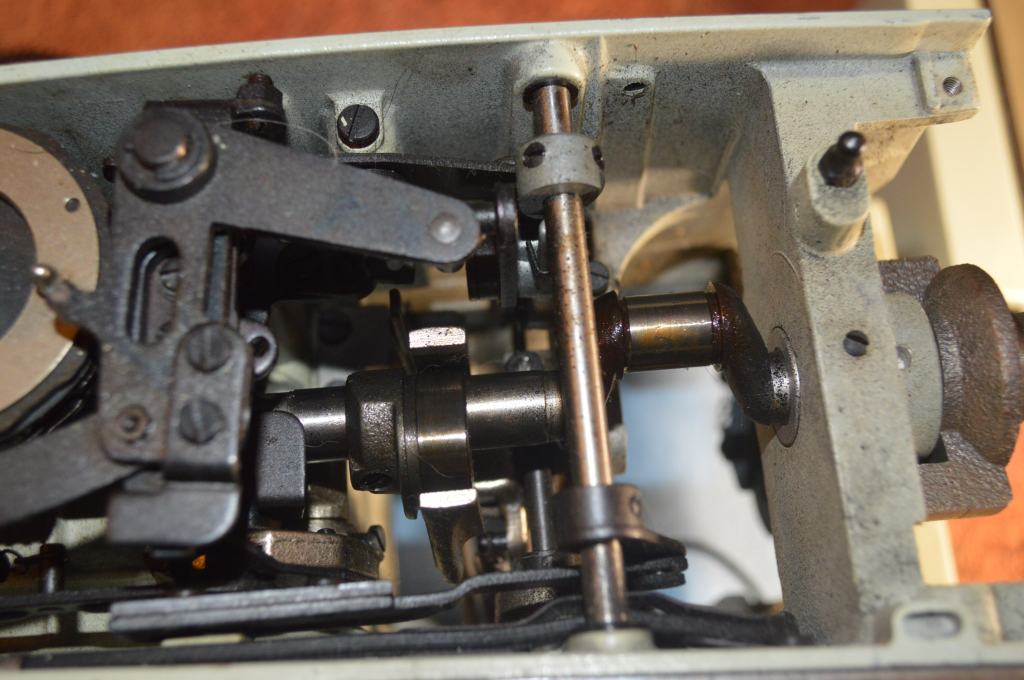

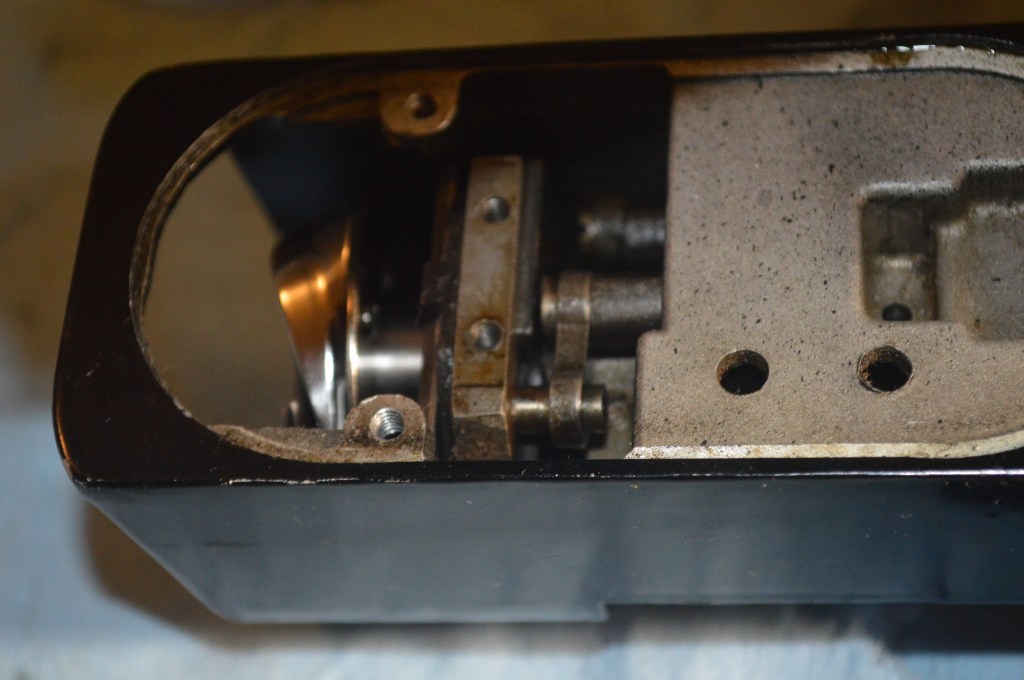

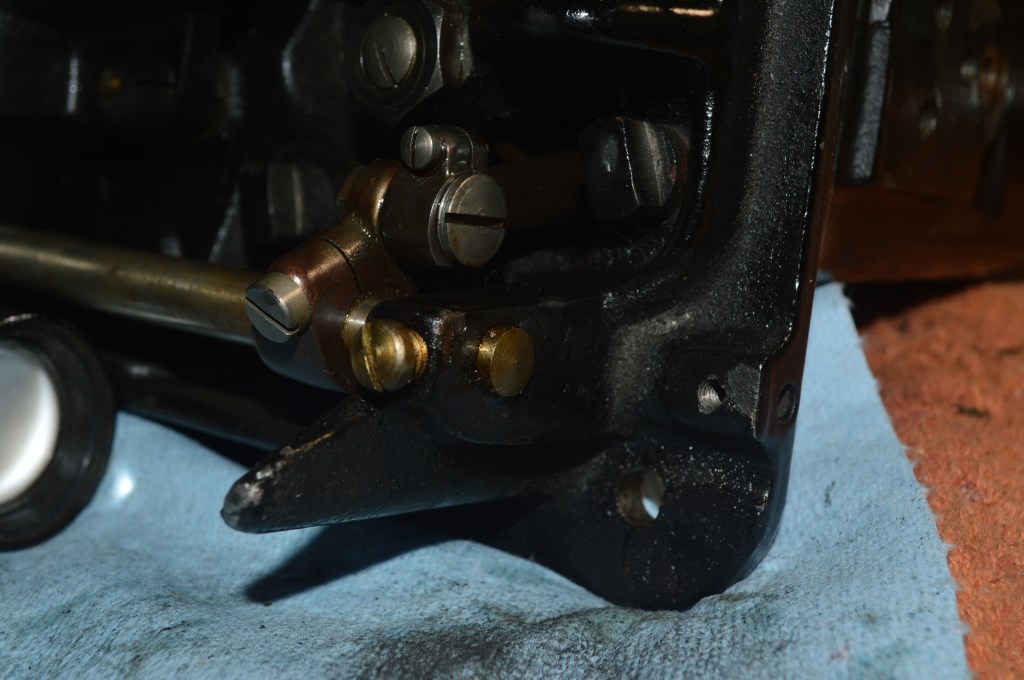

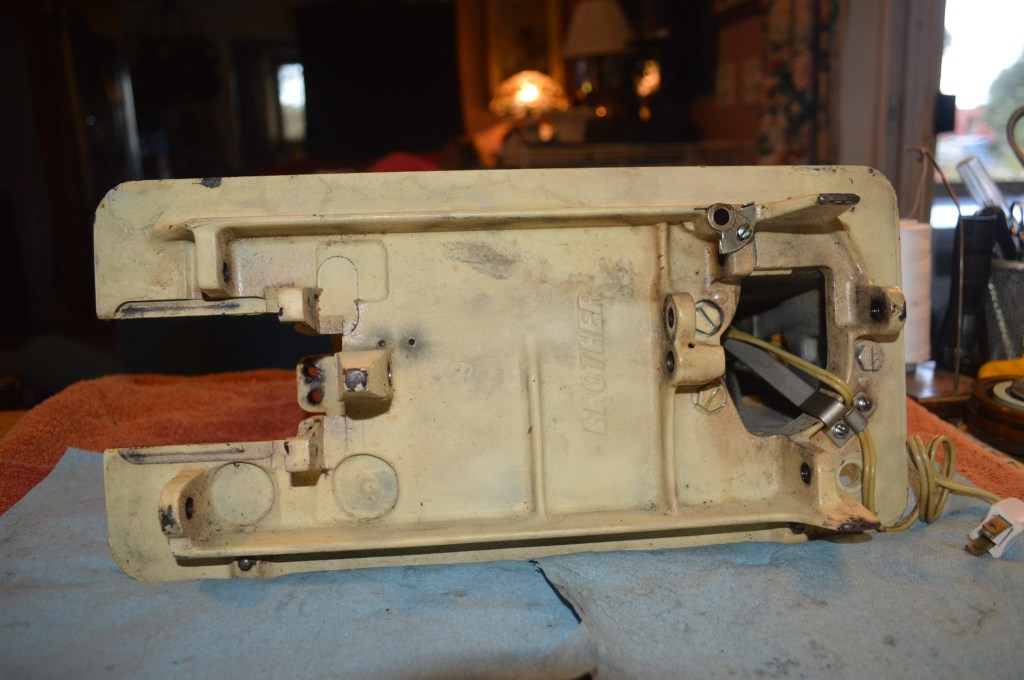

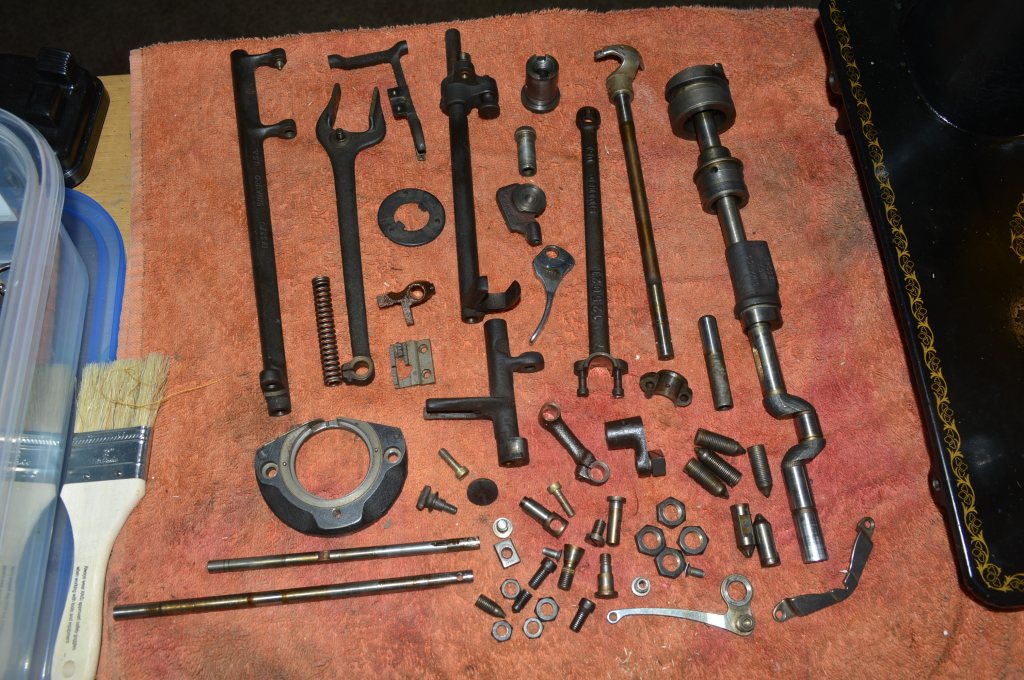

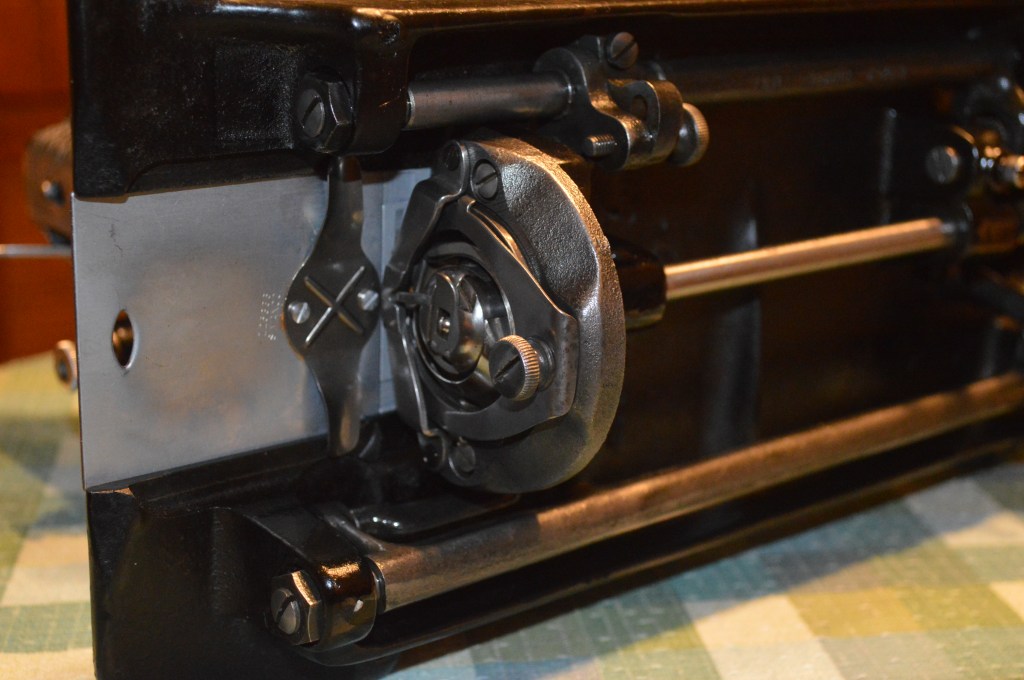

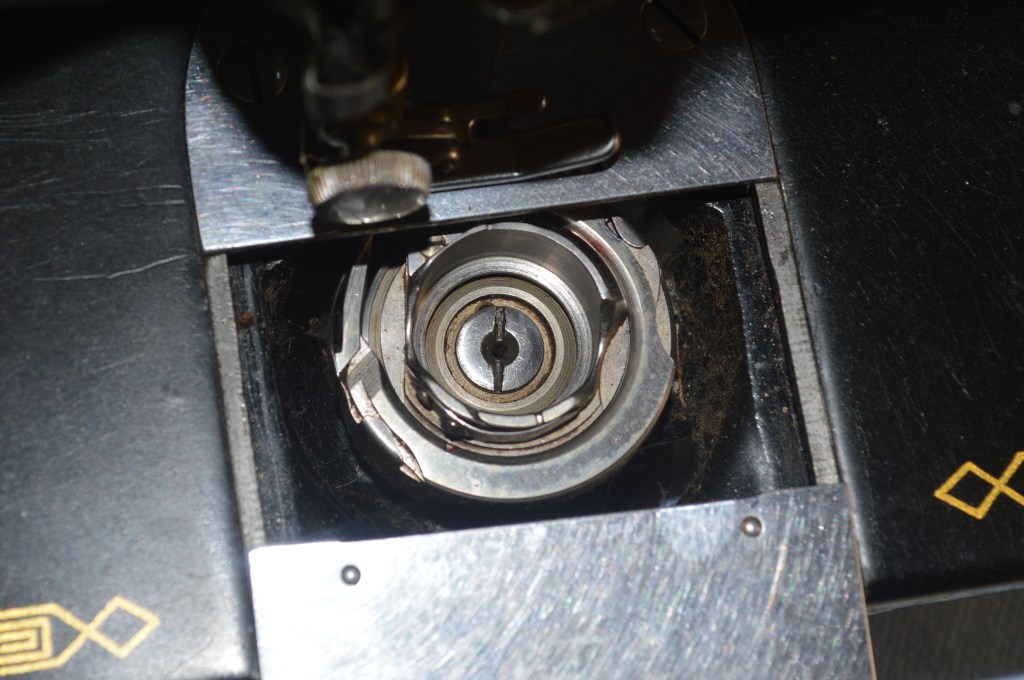

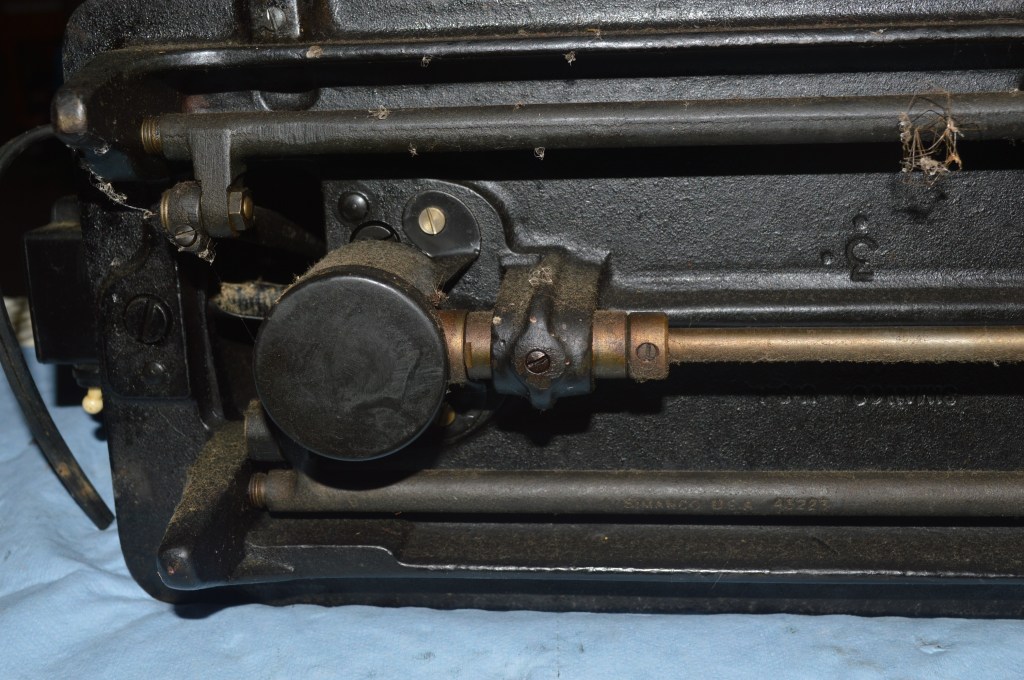

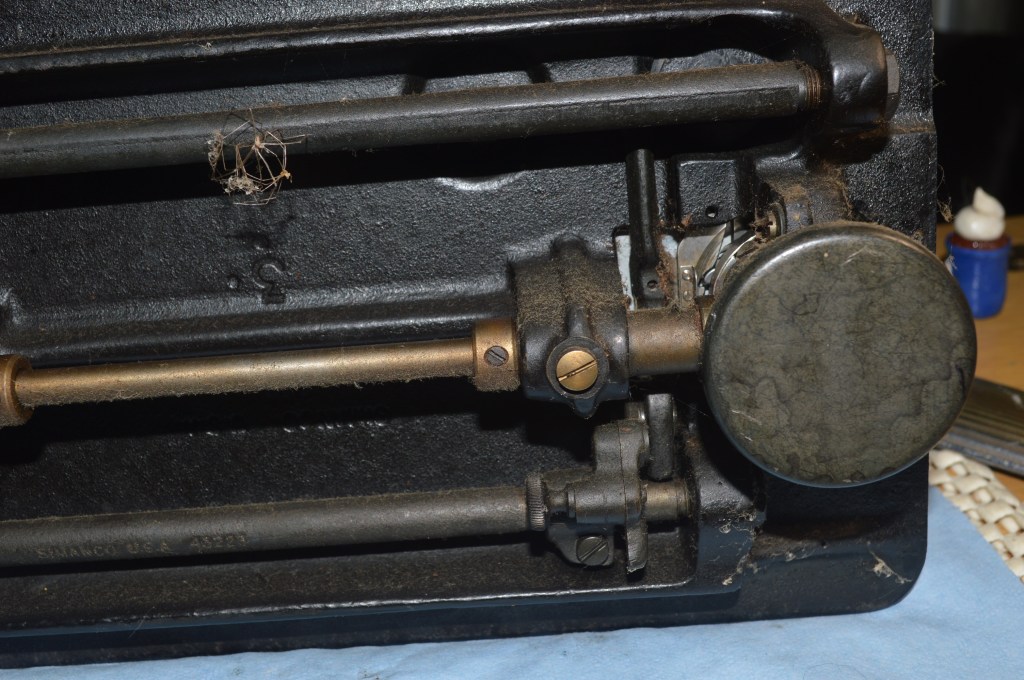

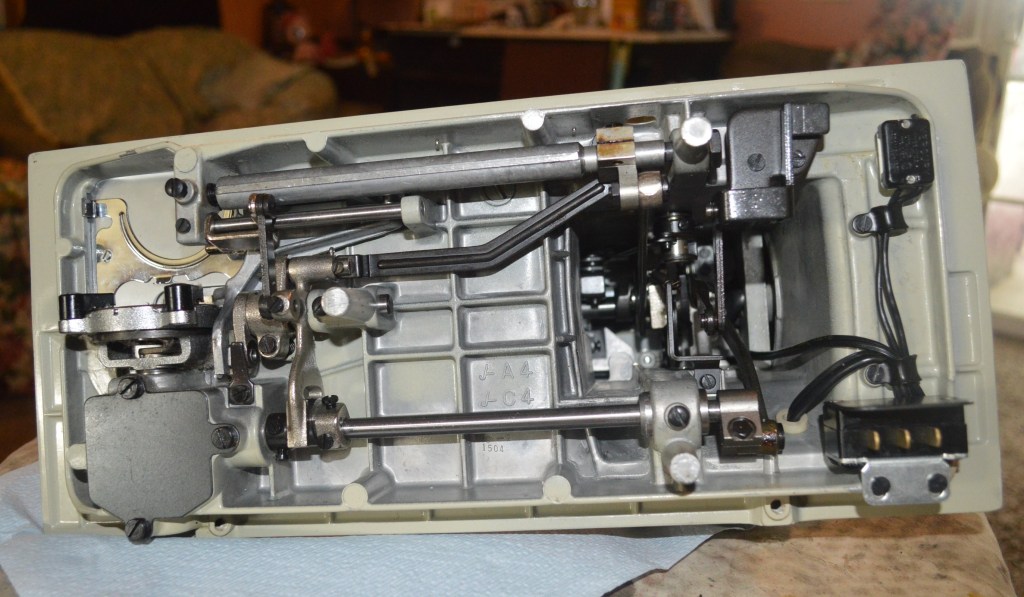

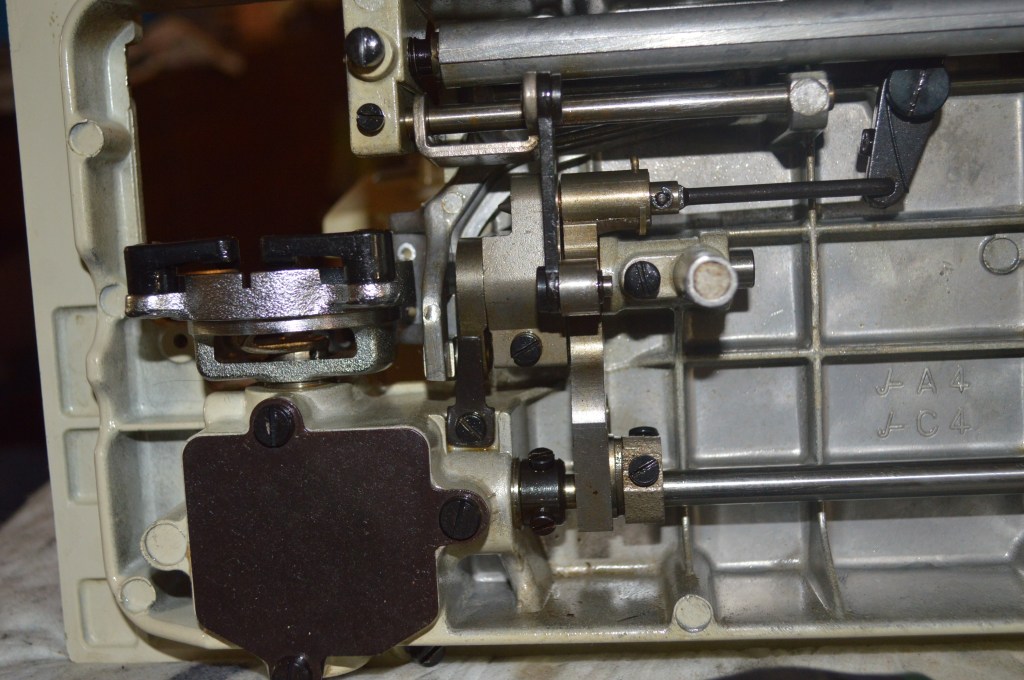

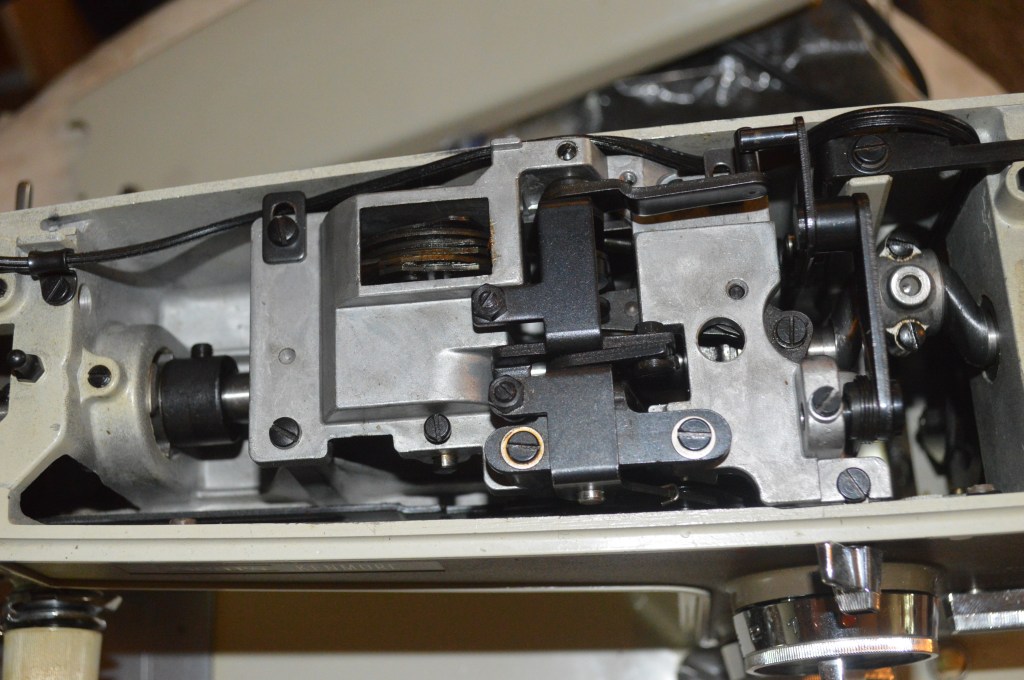

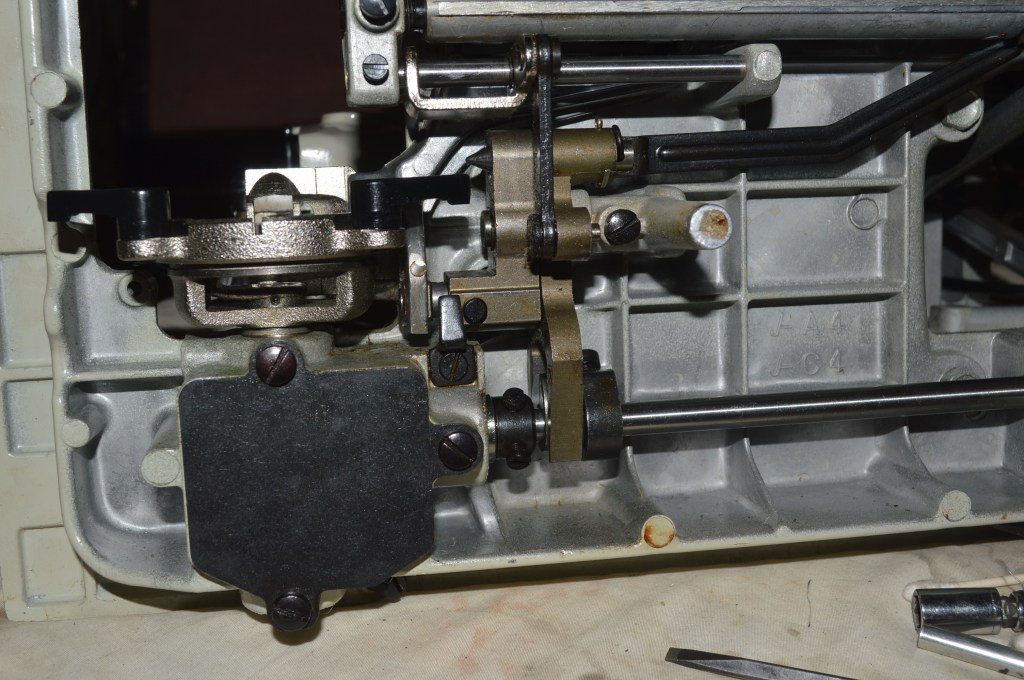

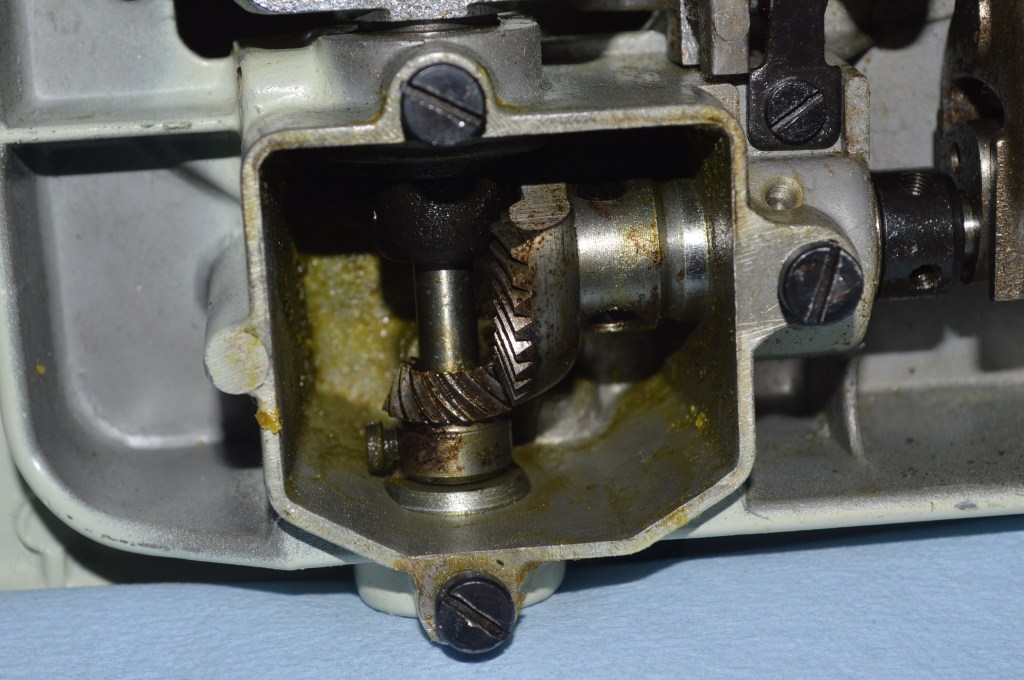

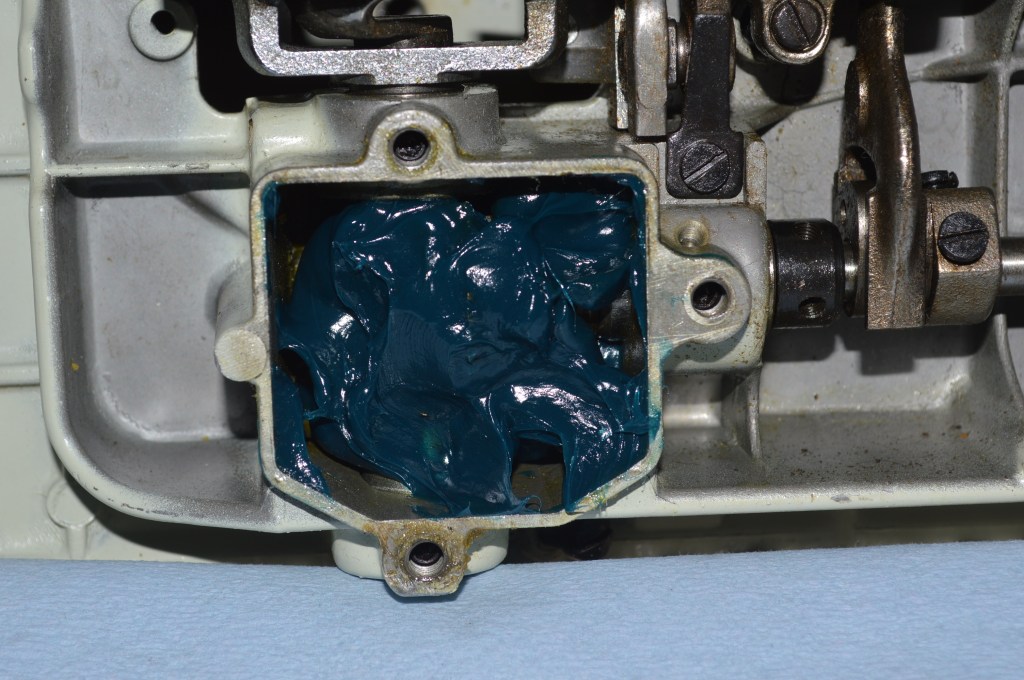

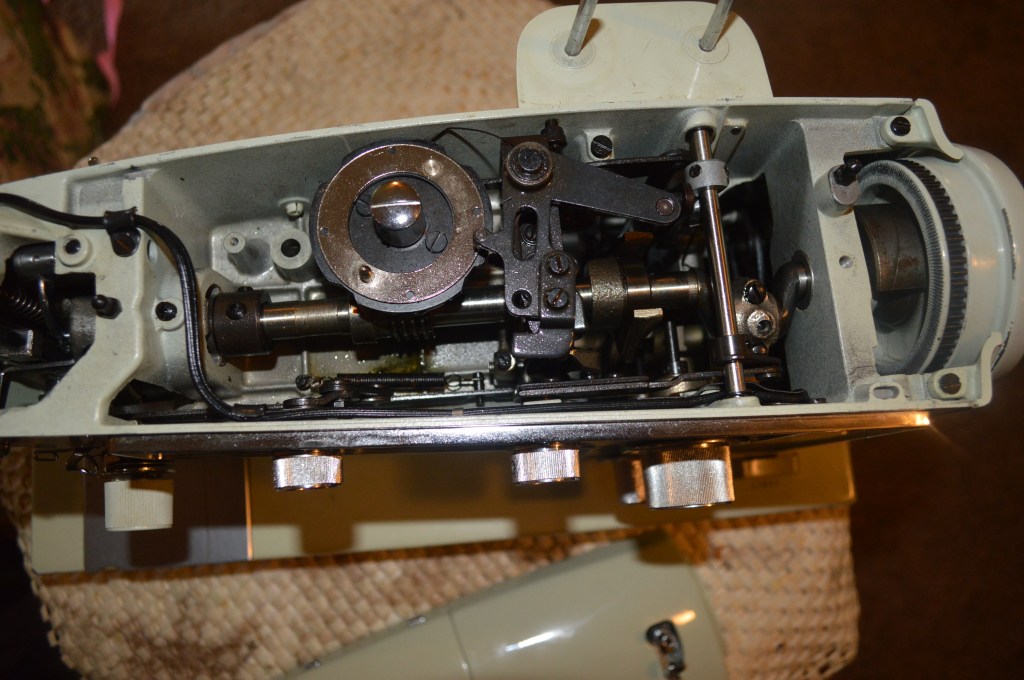

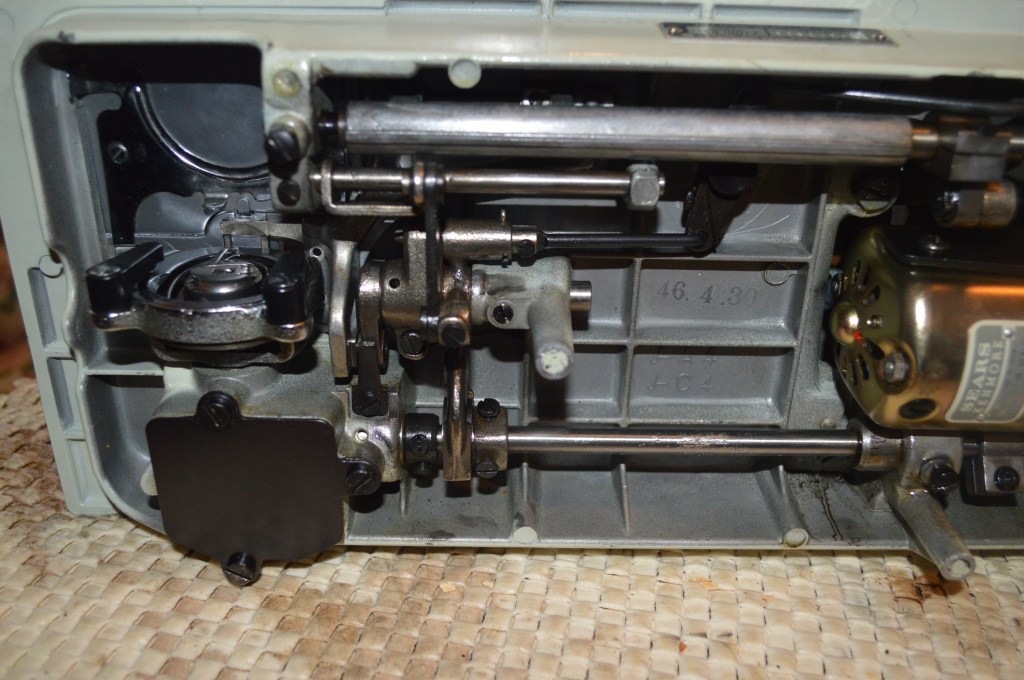

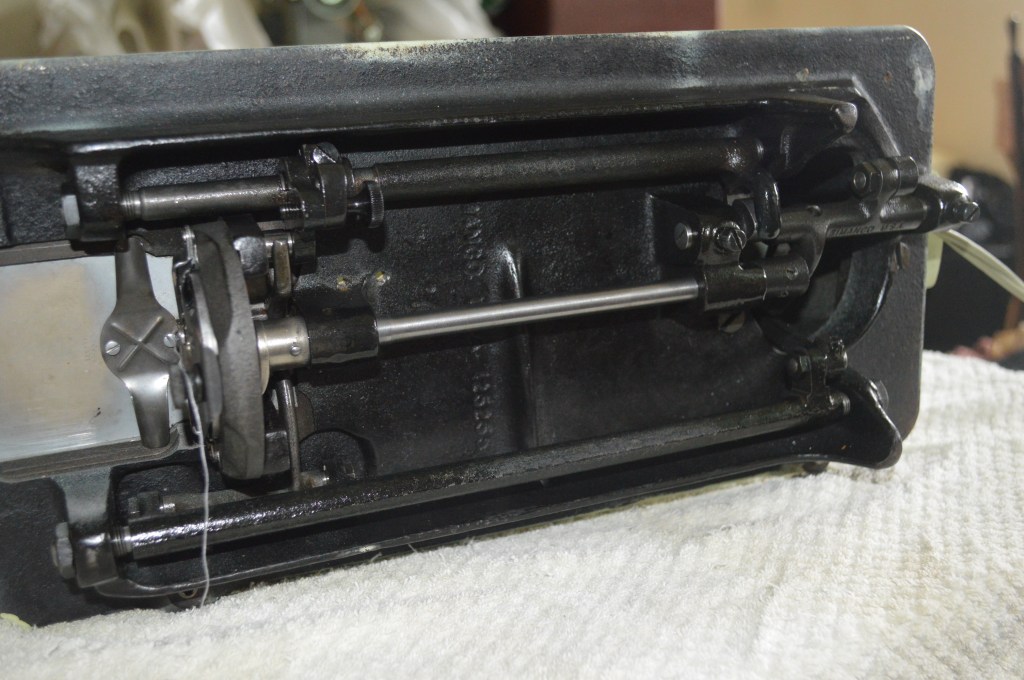

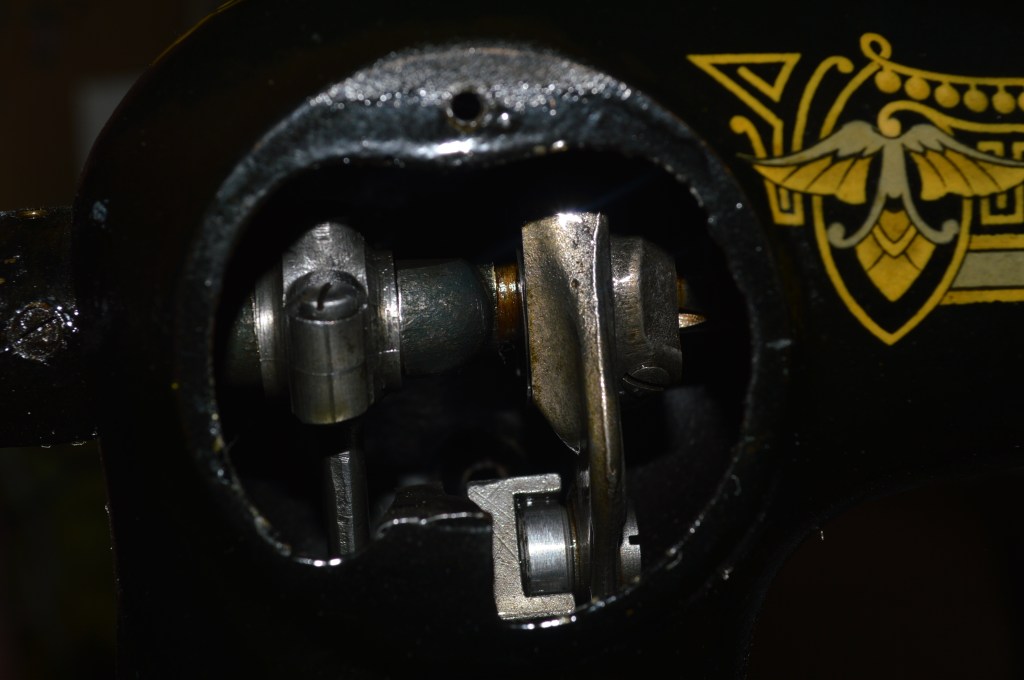

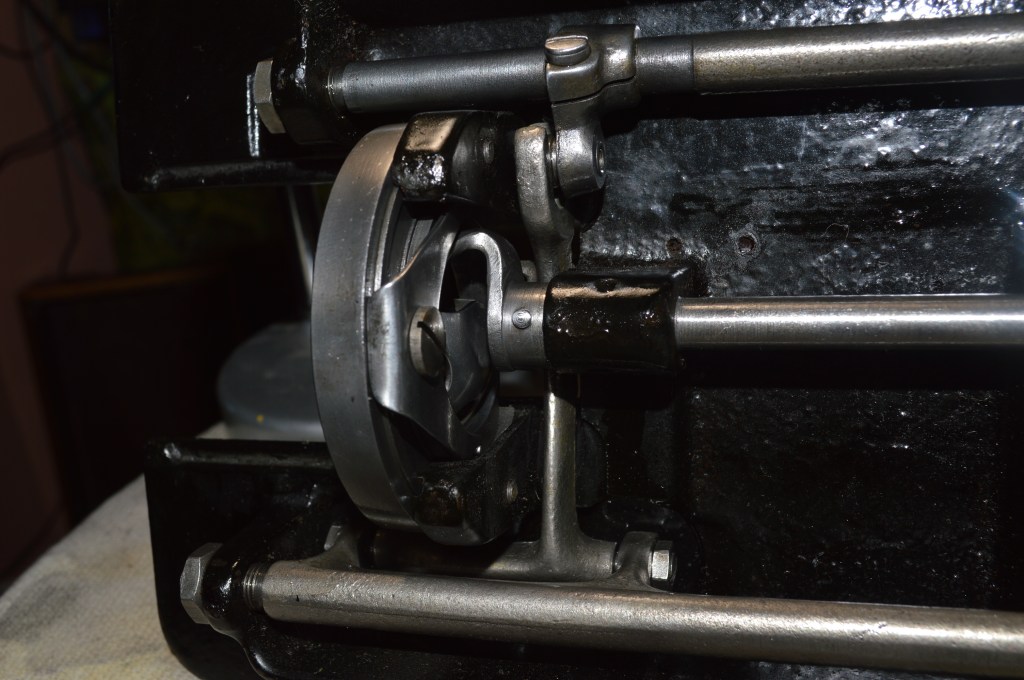

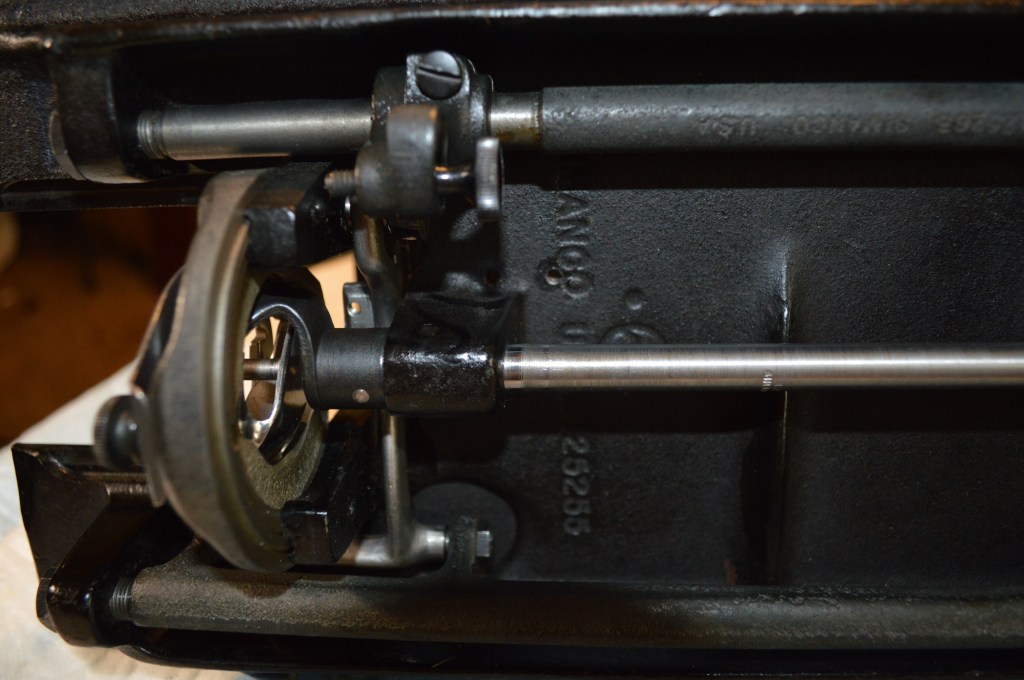

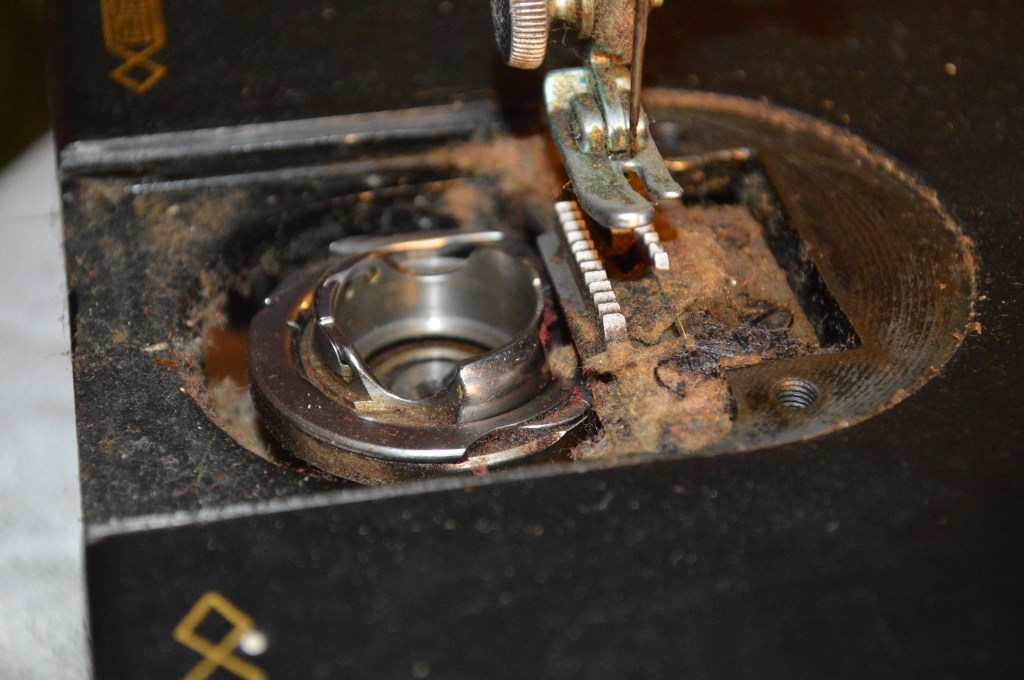

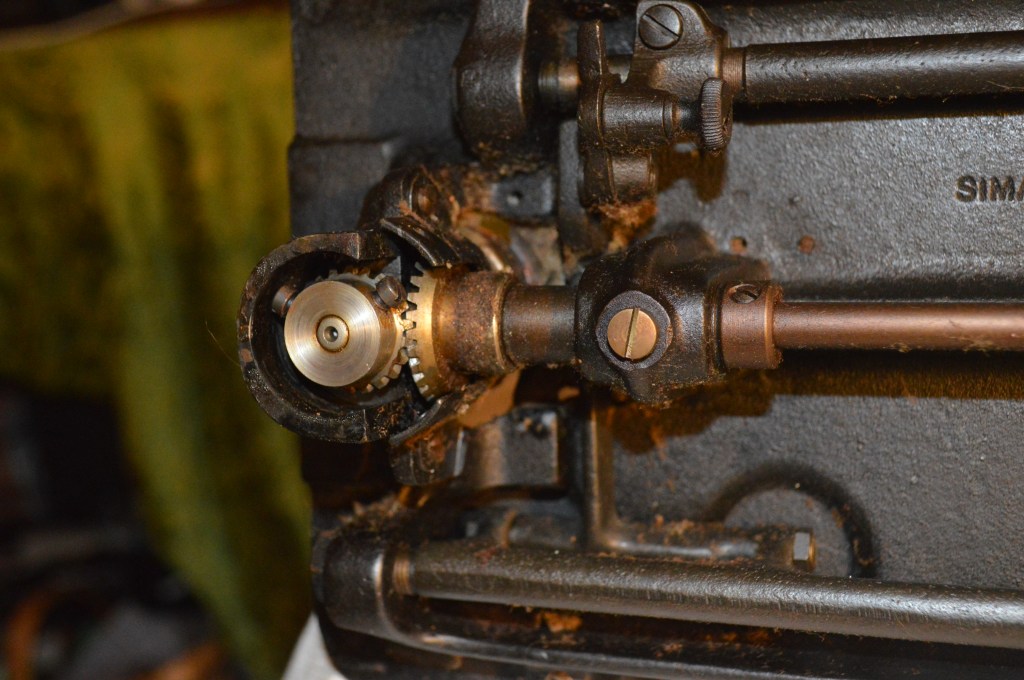

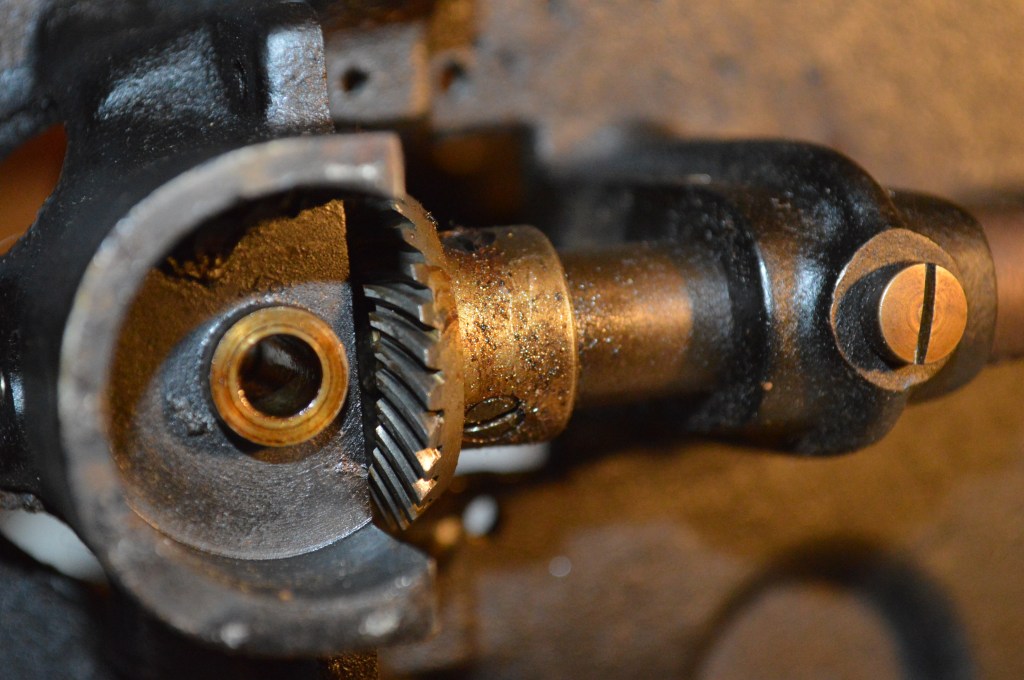

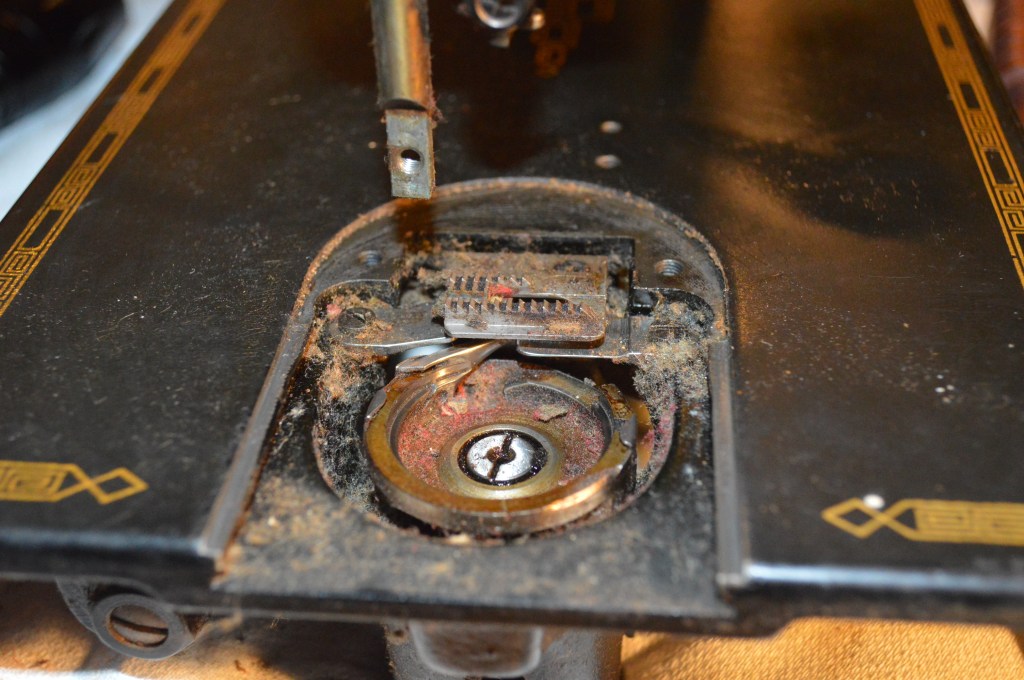

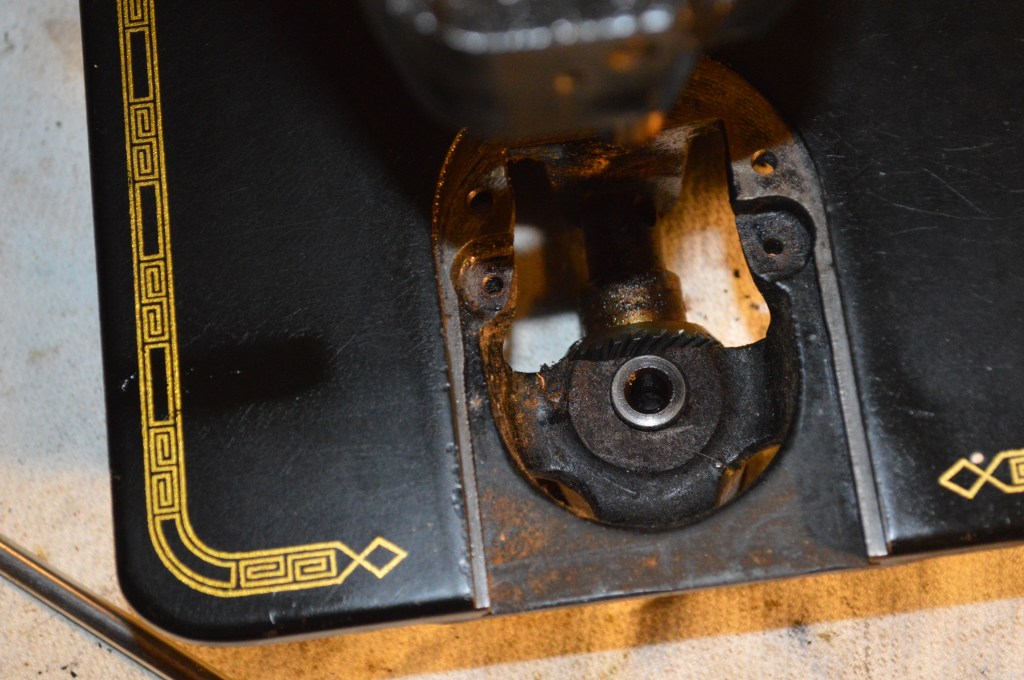

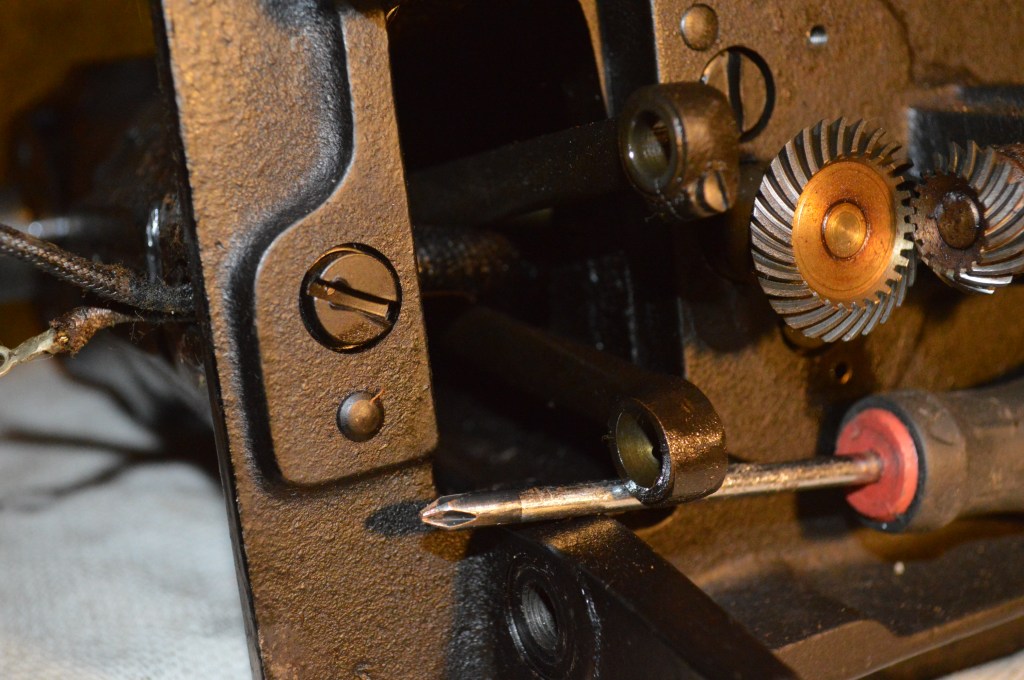

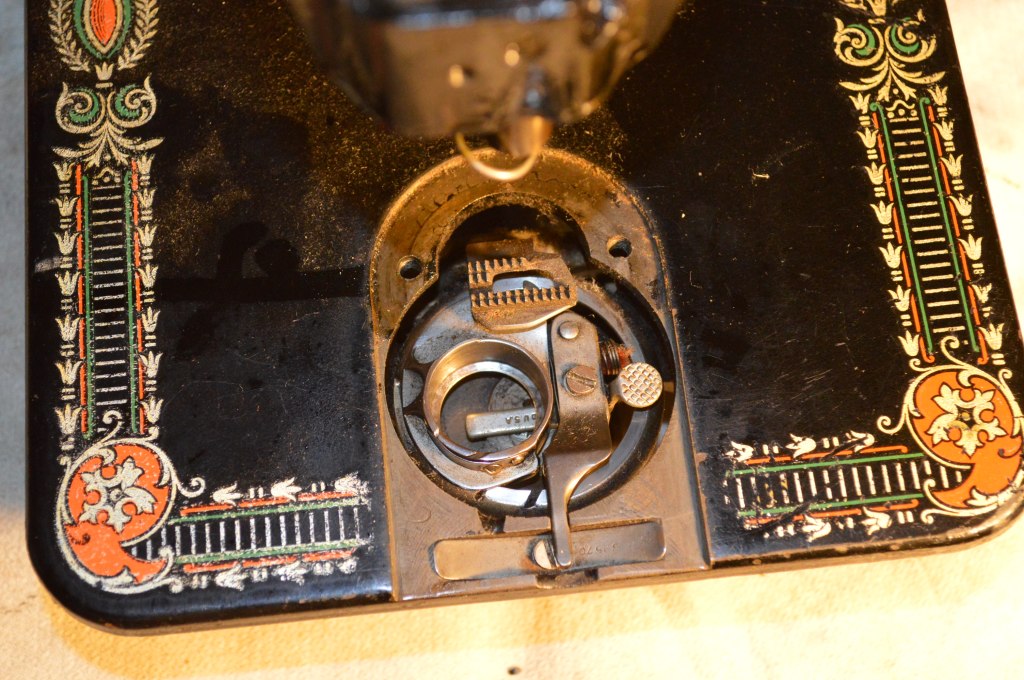

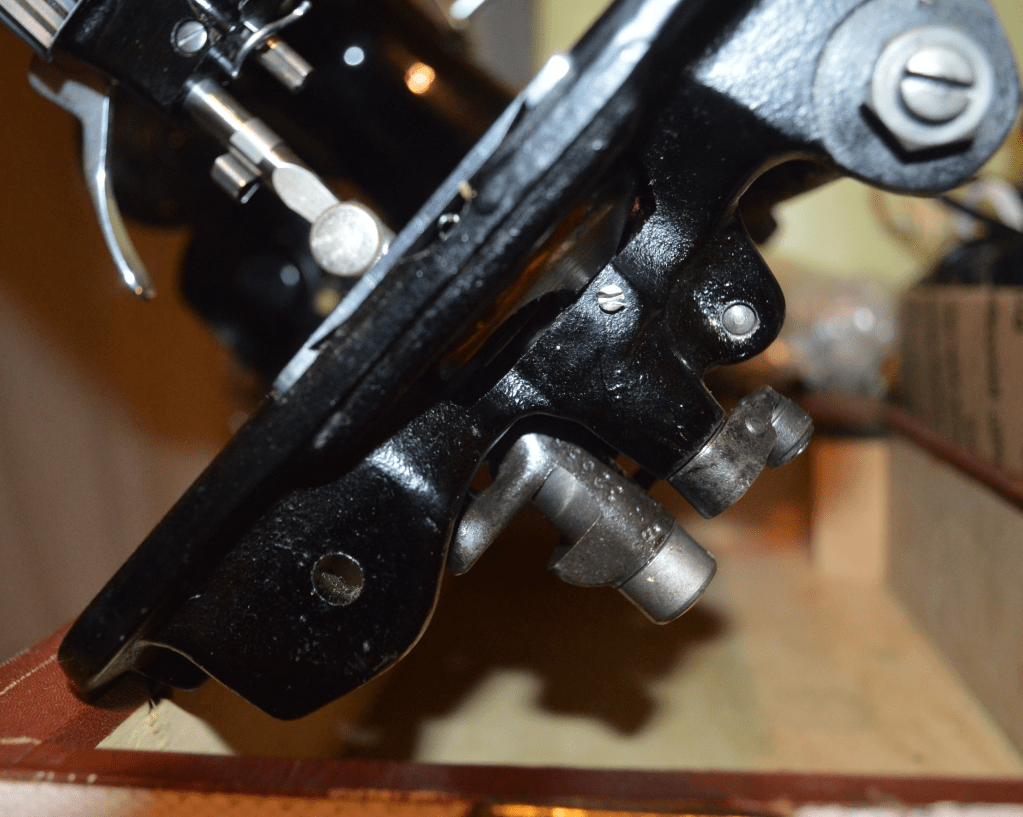

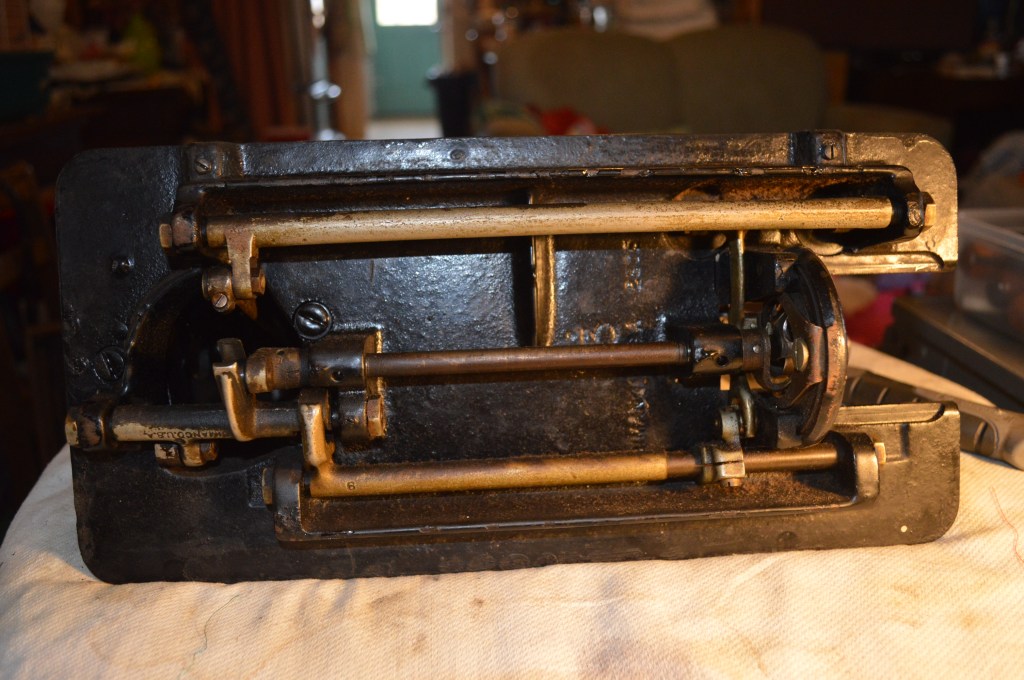

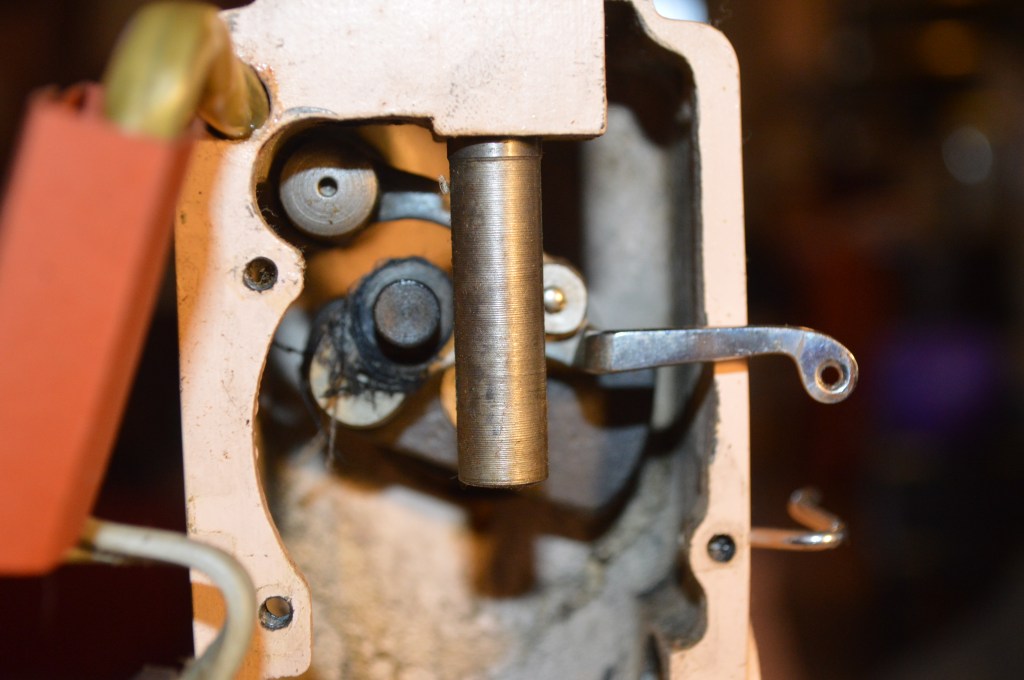

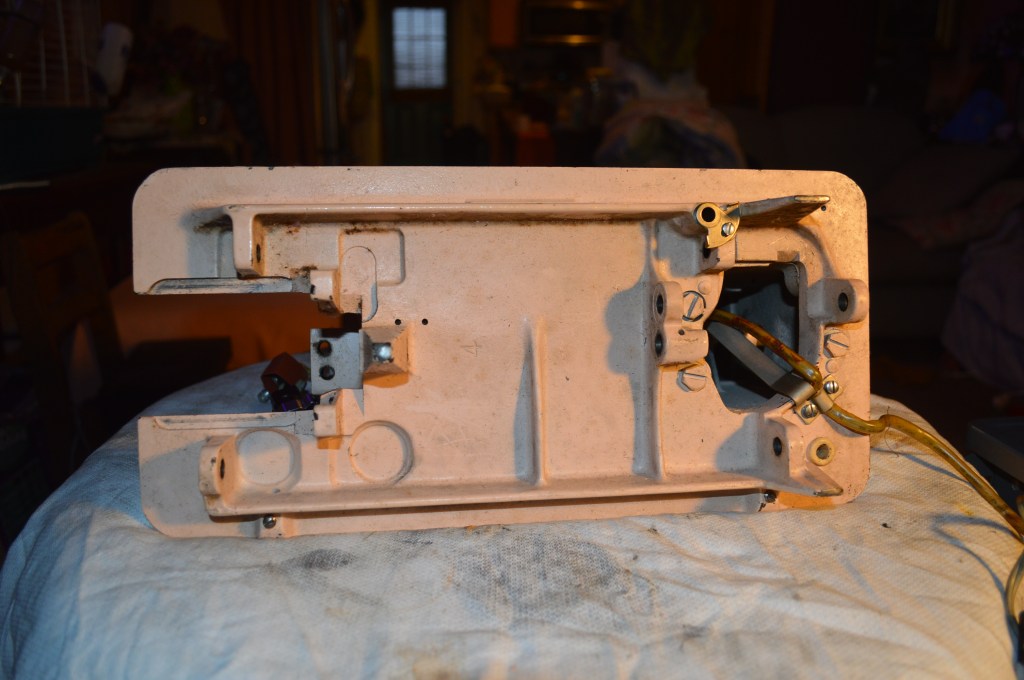

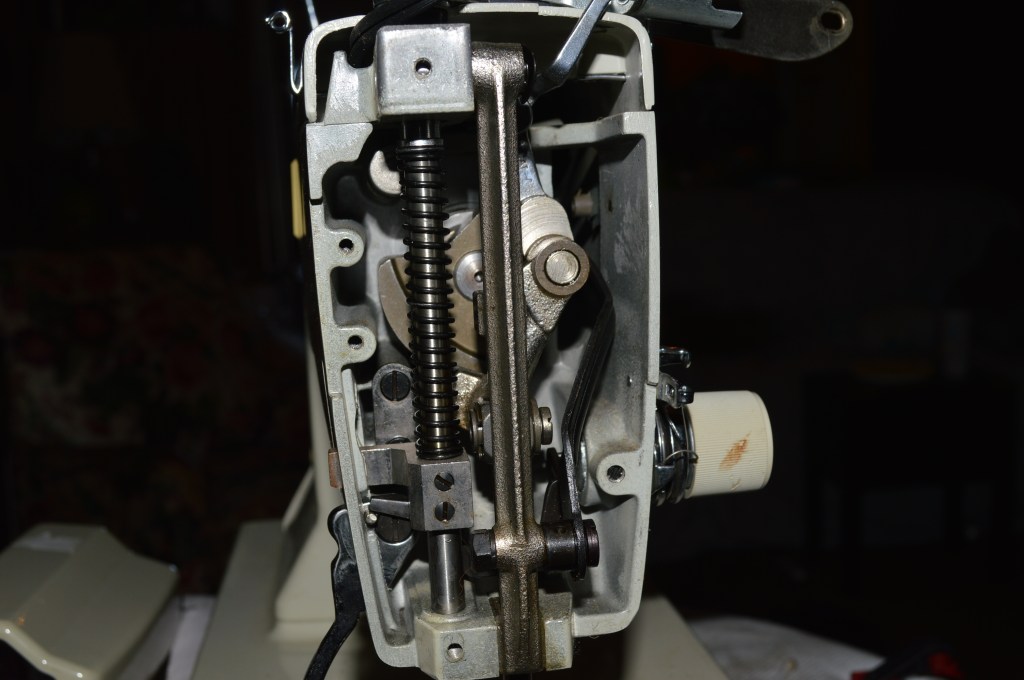

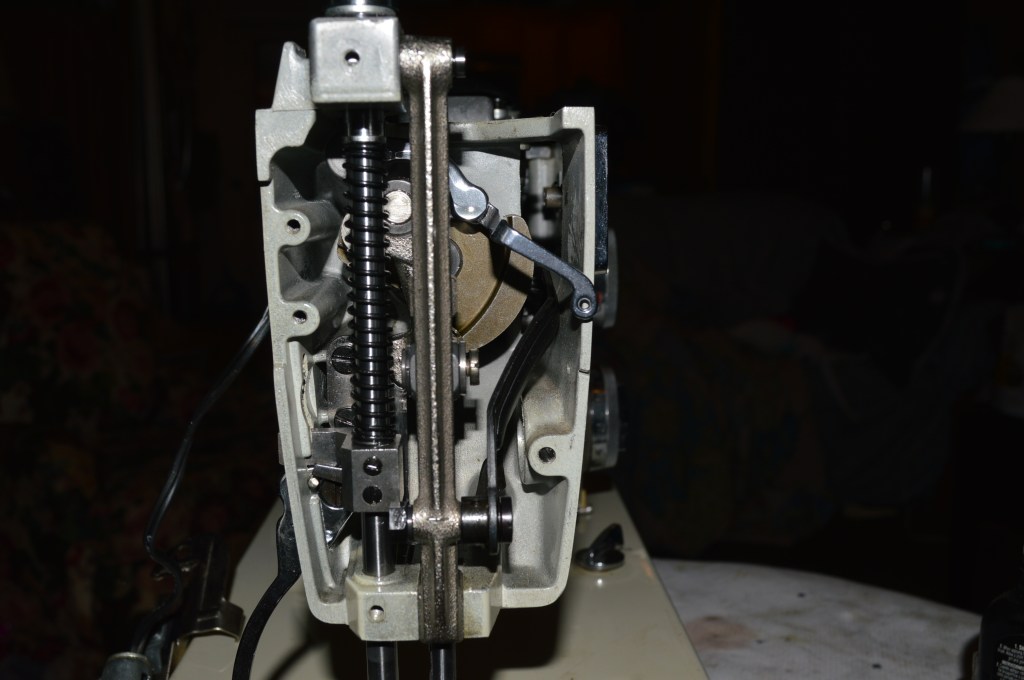

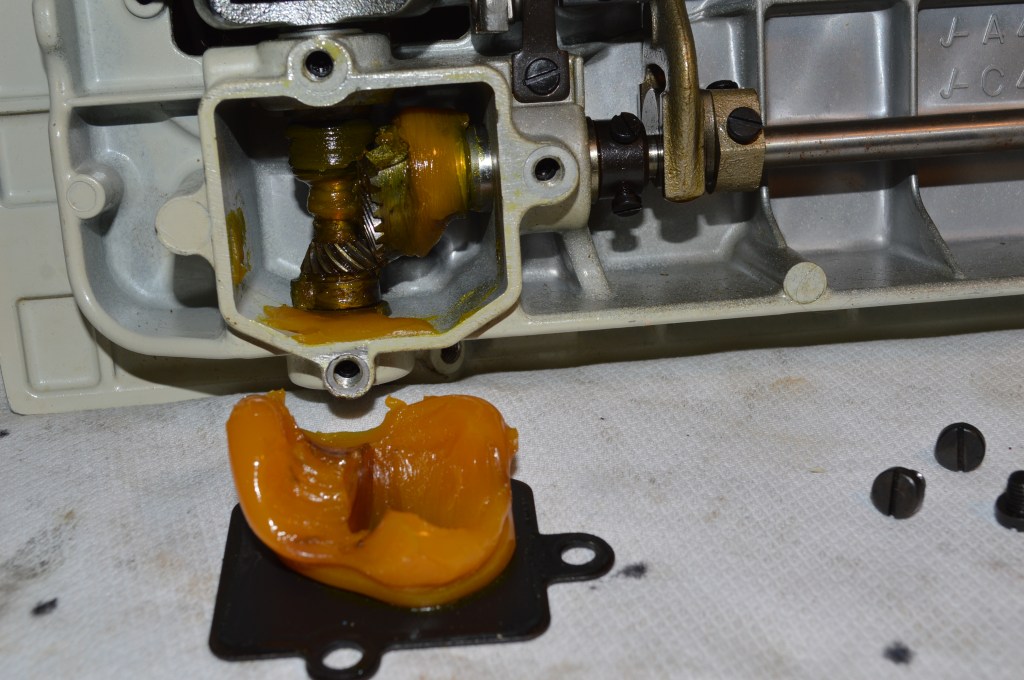

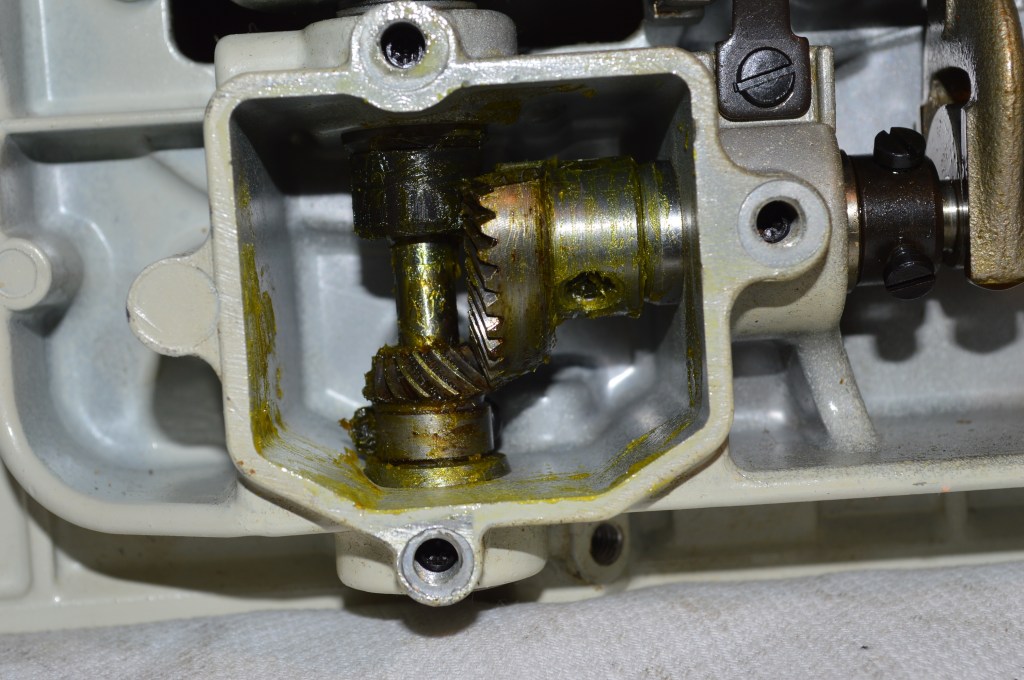

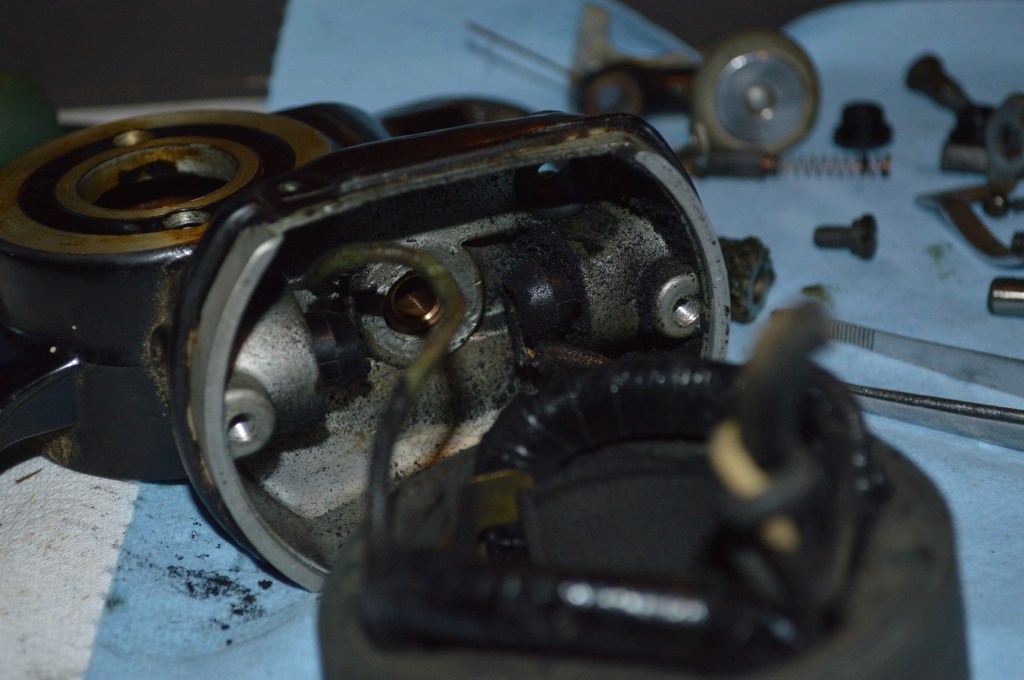

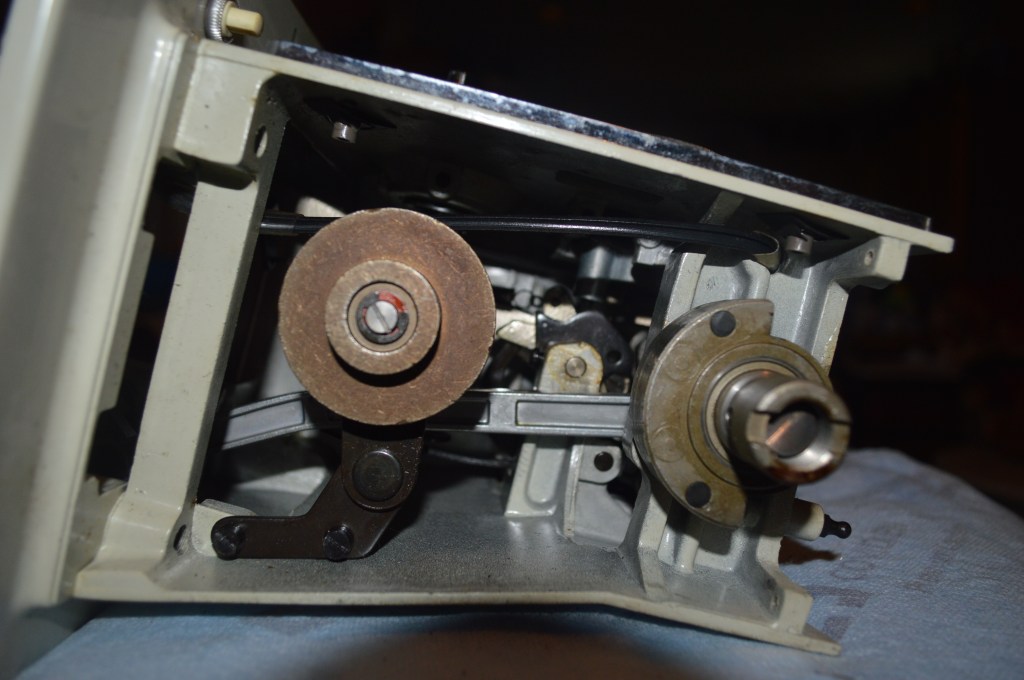

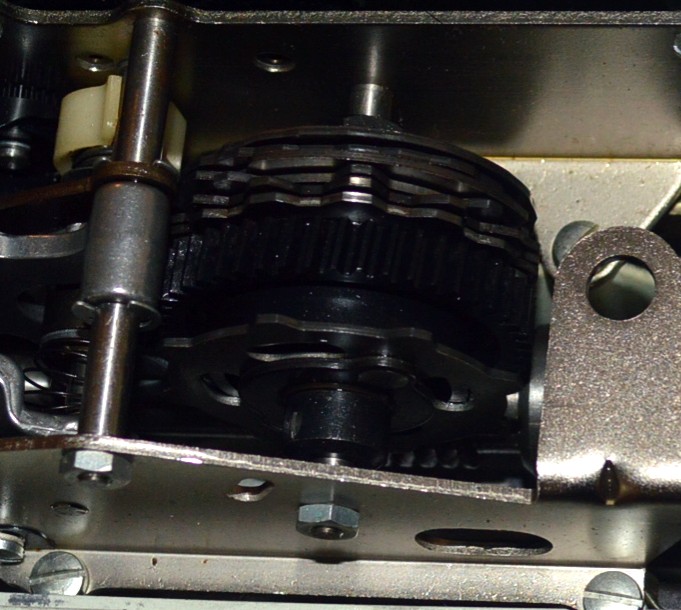

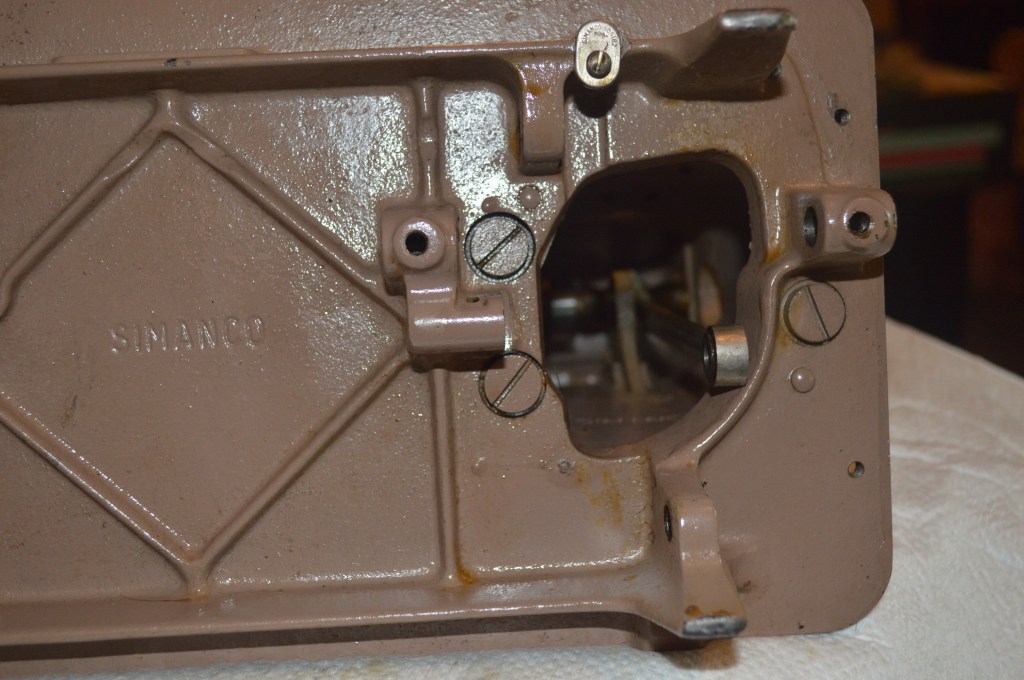

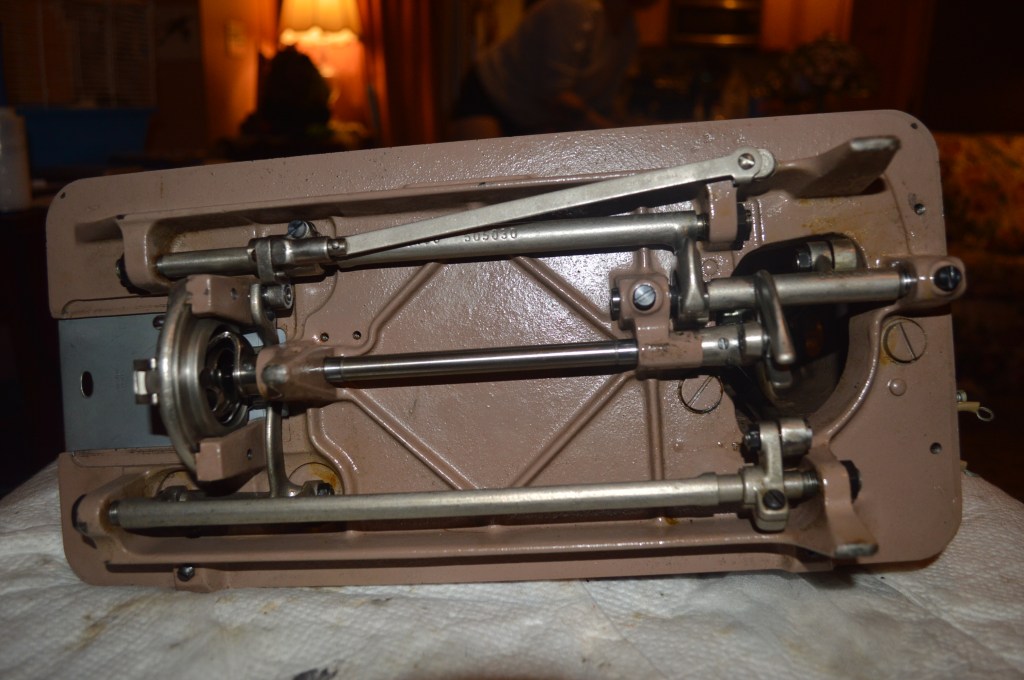

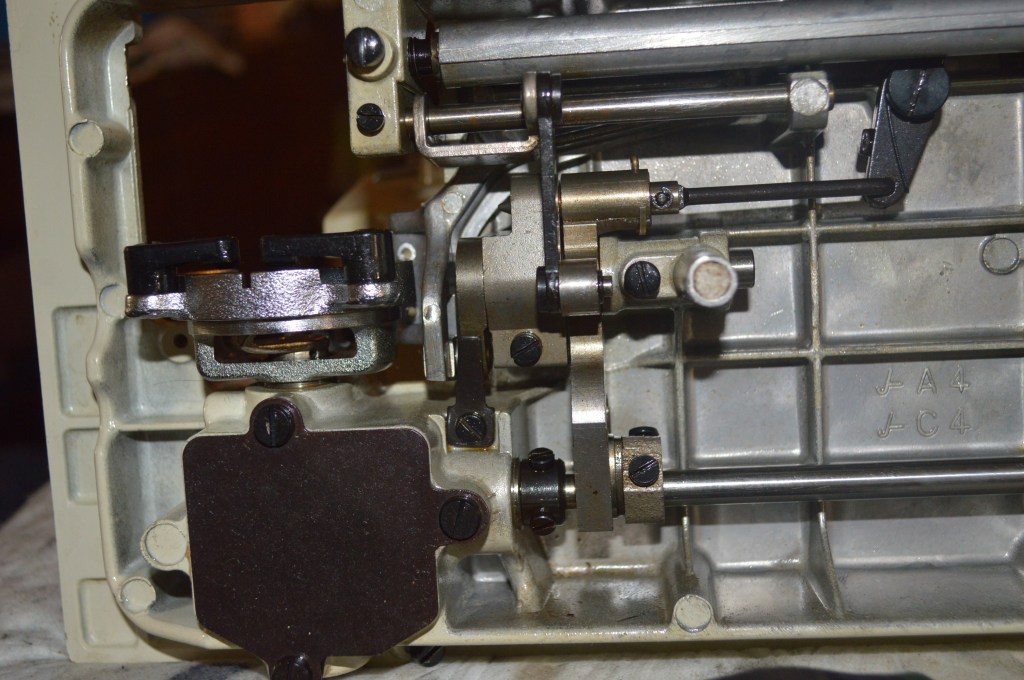

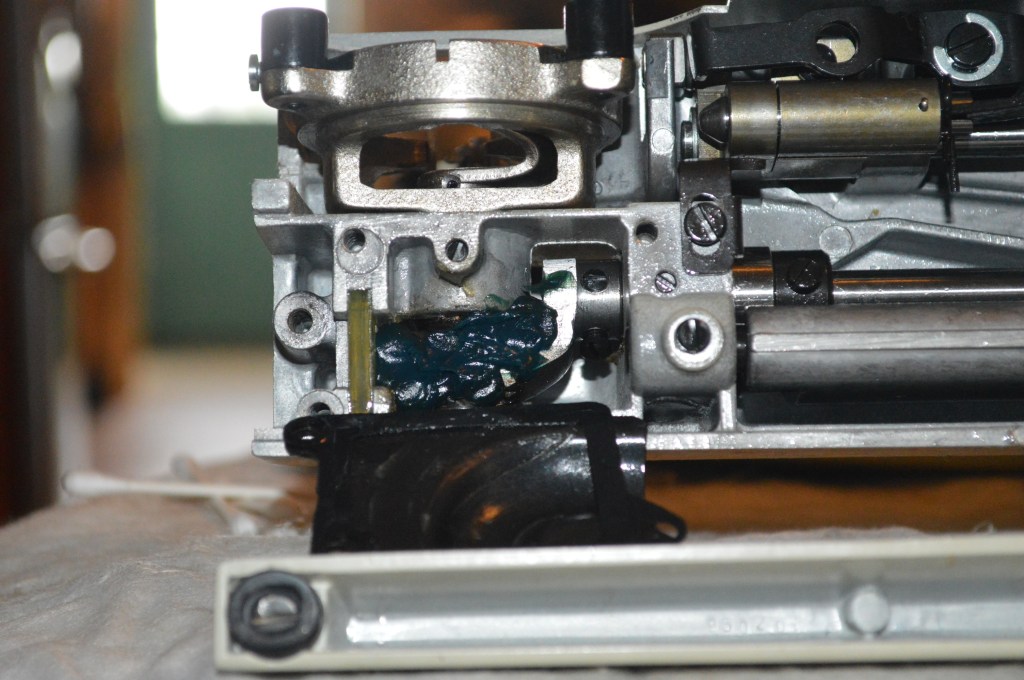

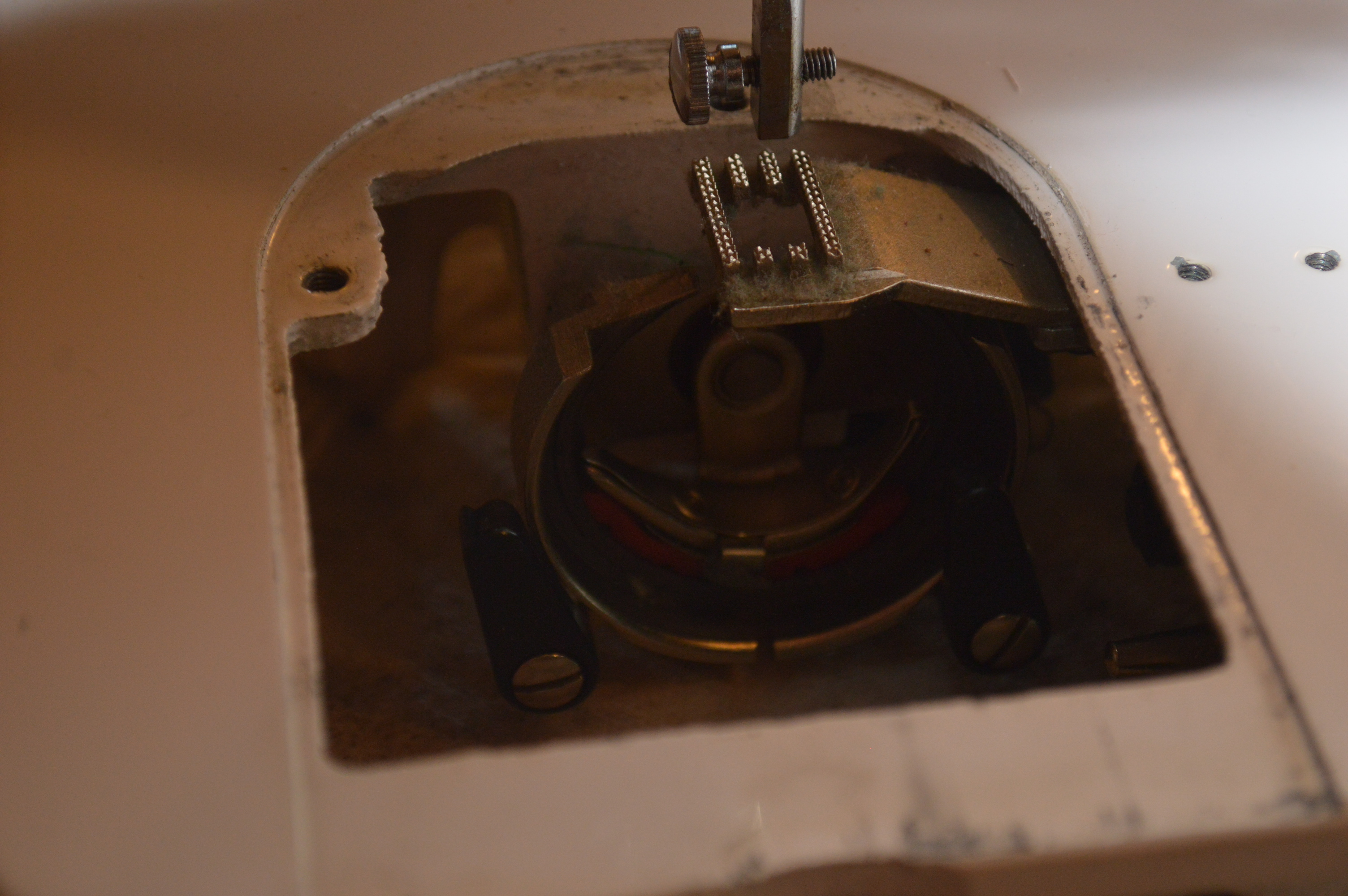

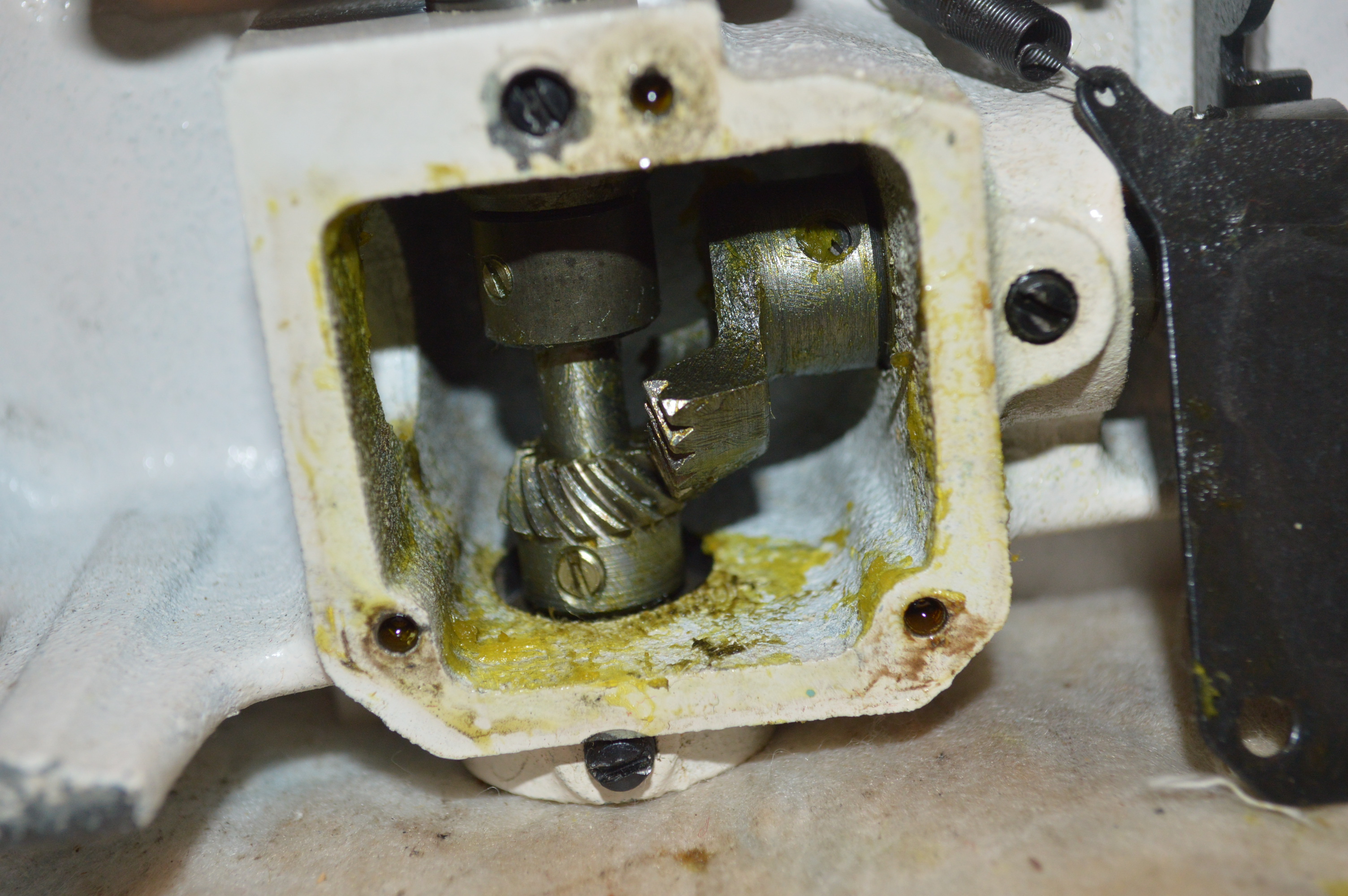

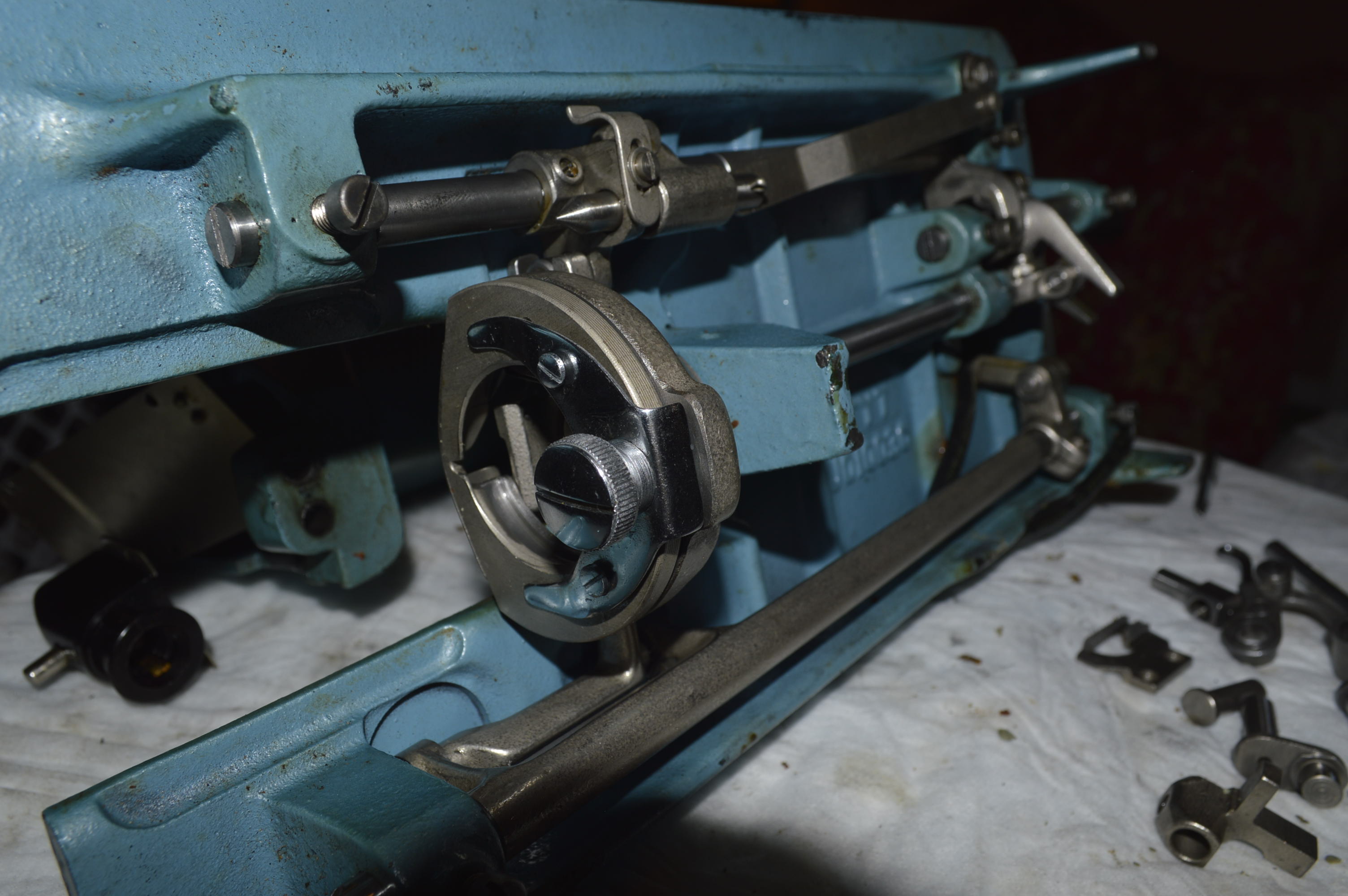

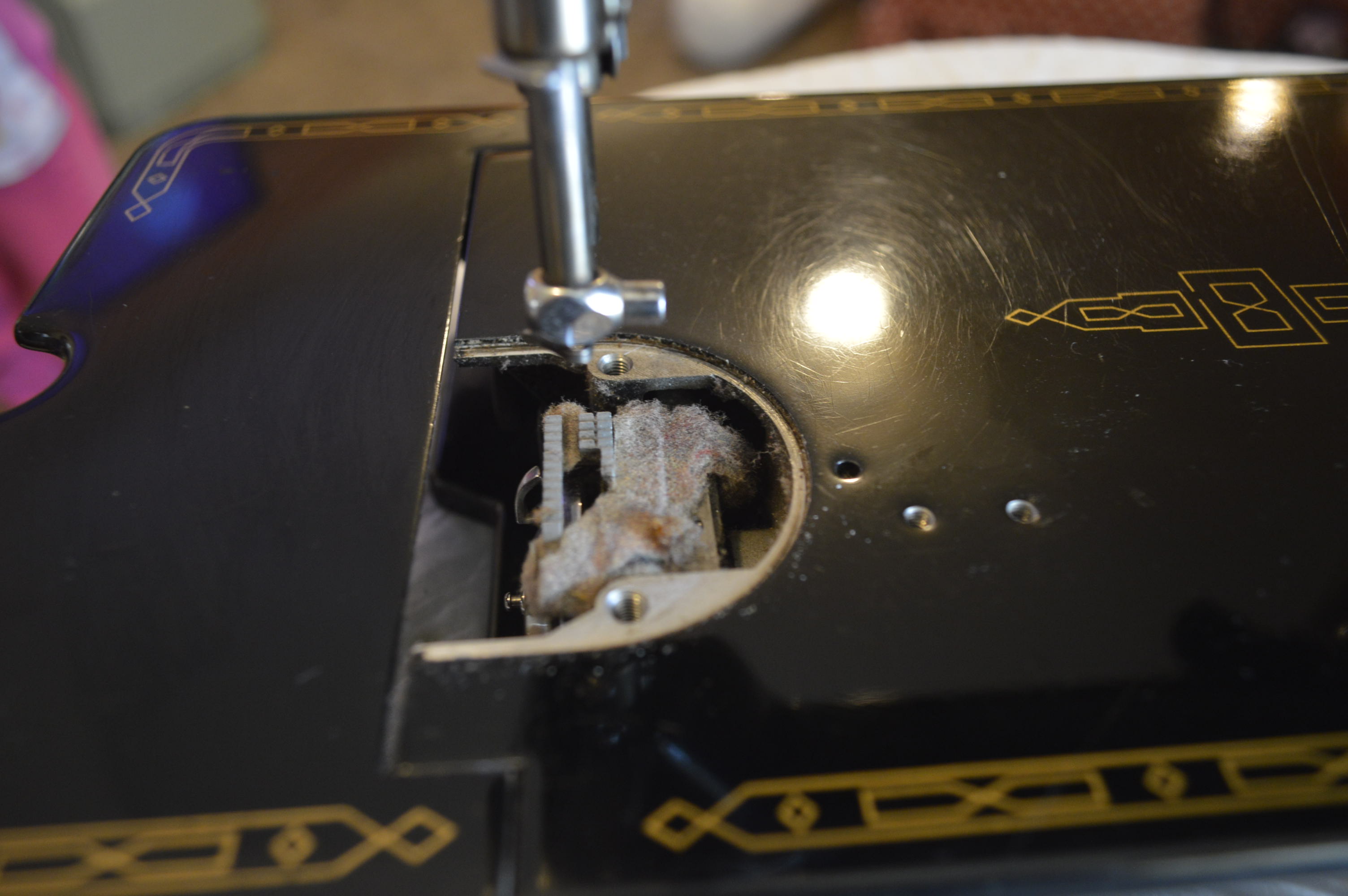

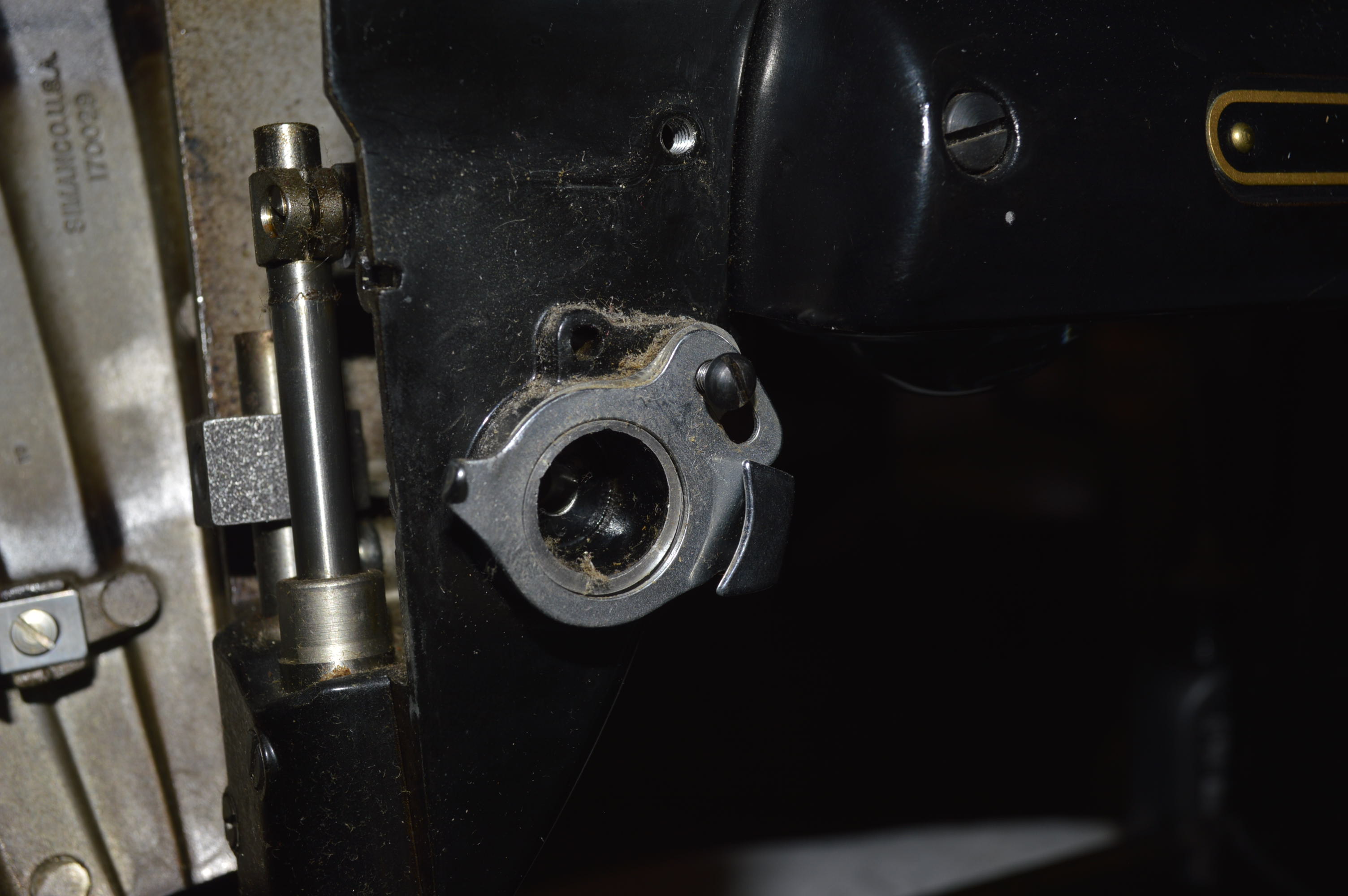

Next, all of the assemblies are removed from under the bed.

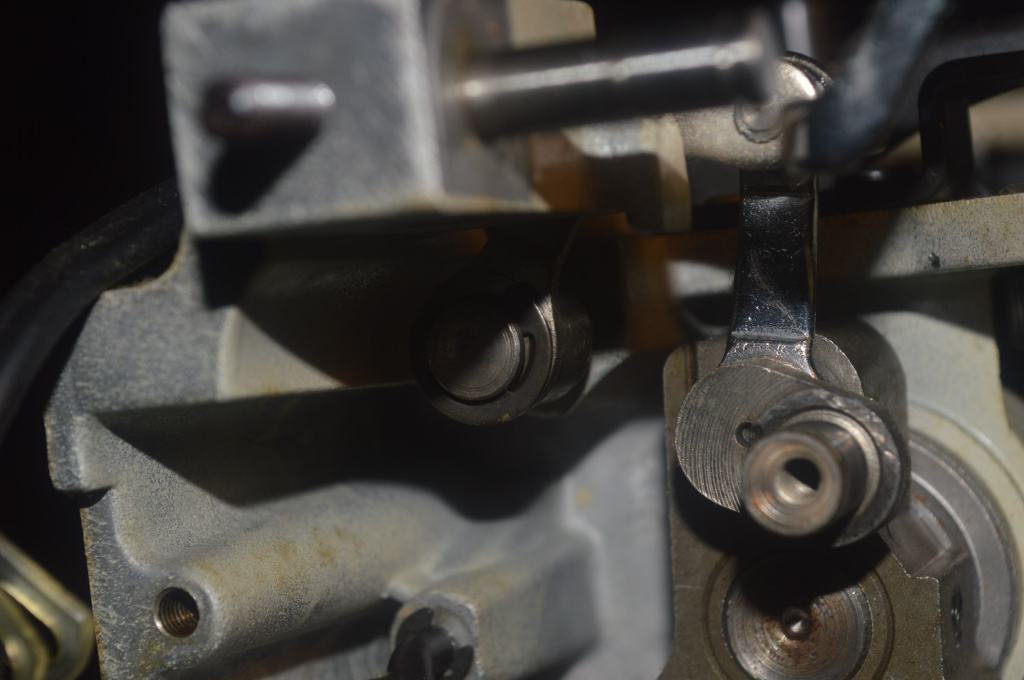

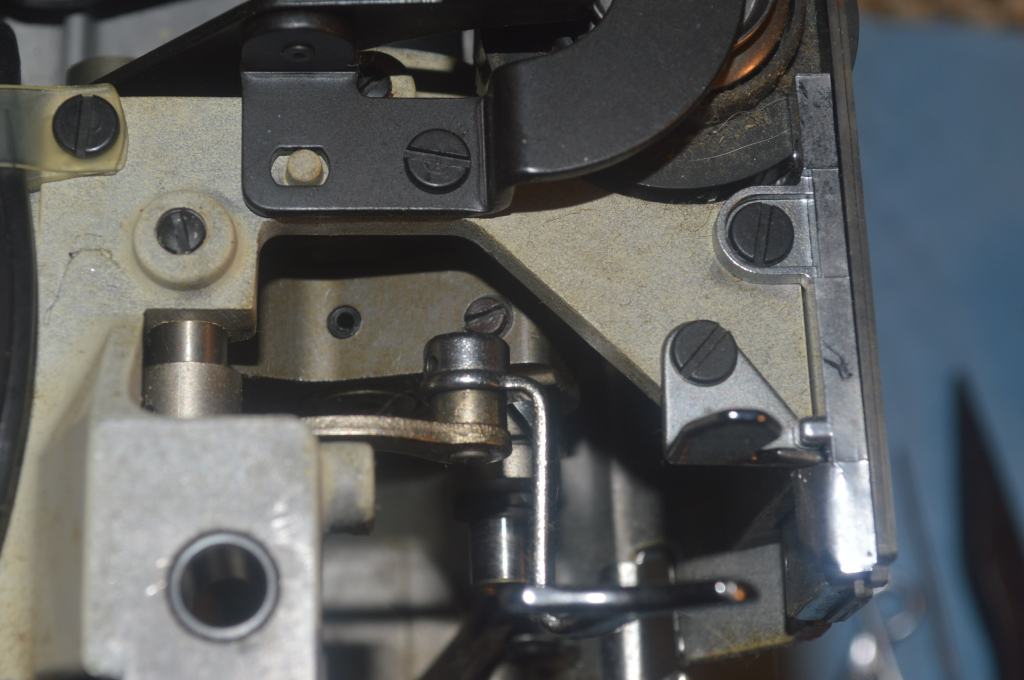

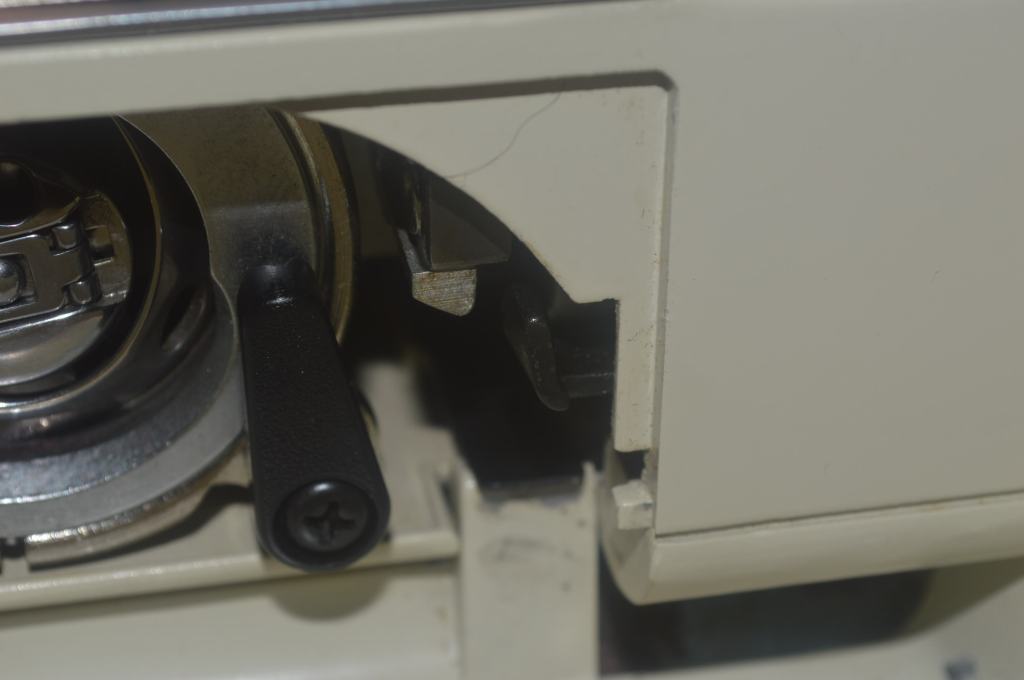

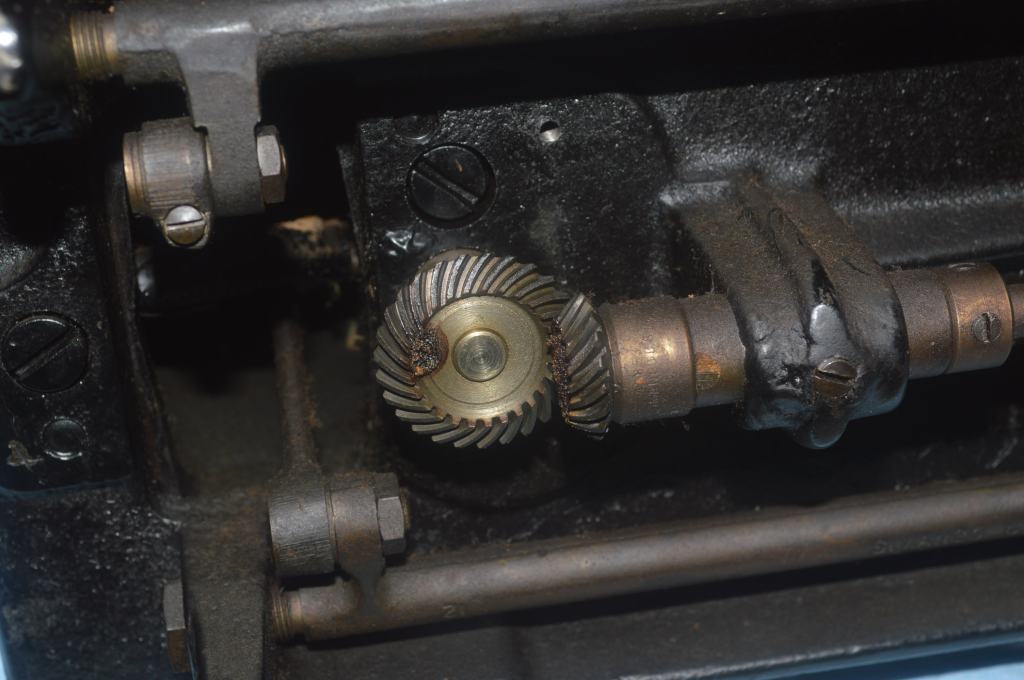

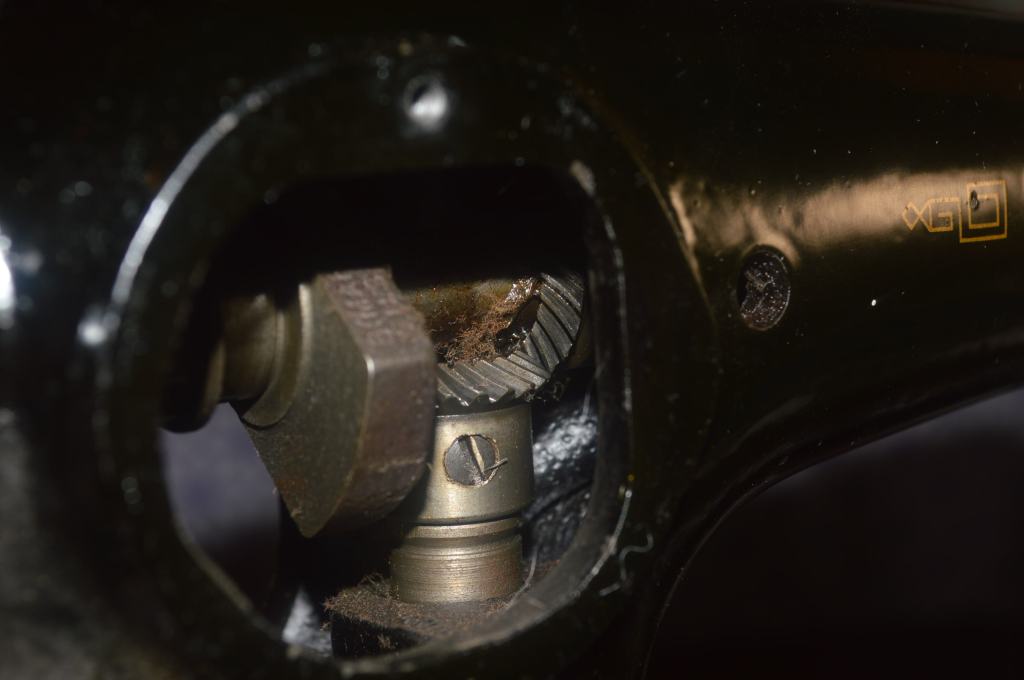

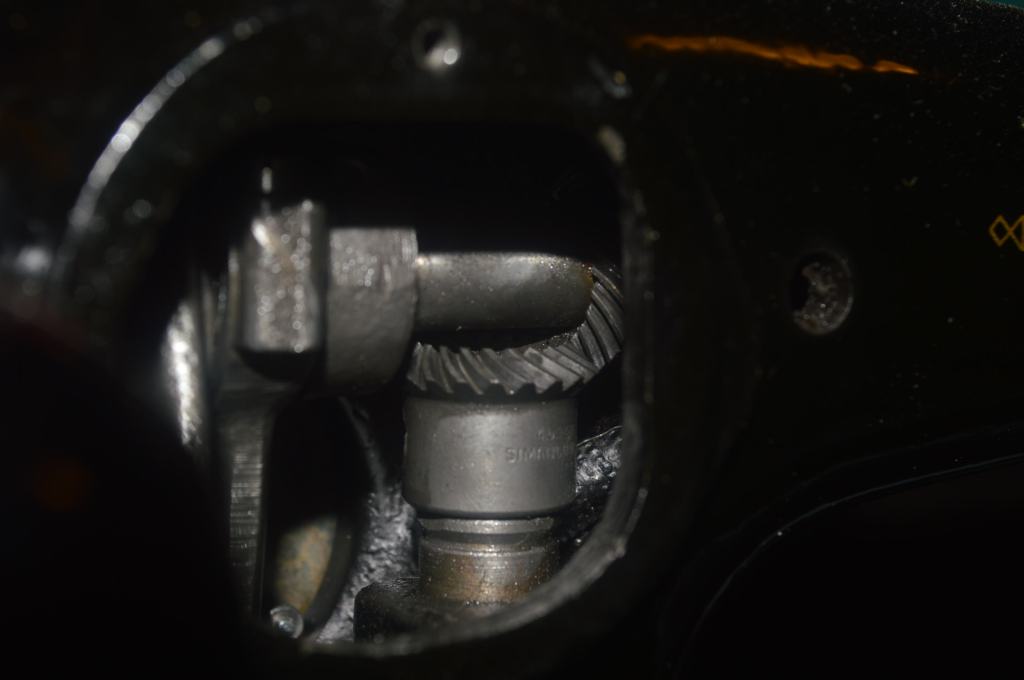

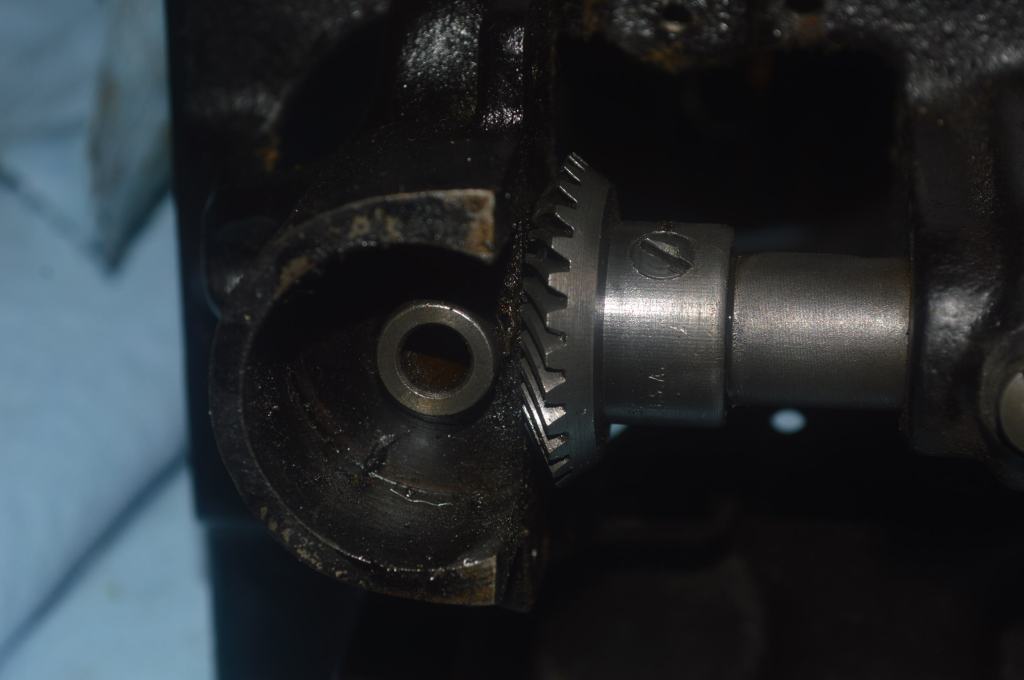

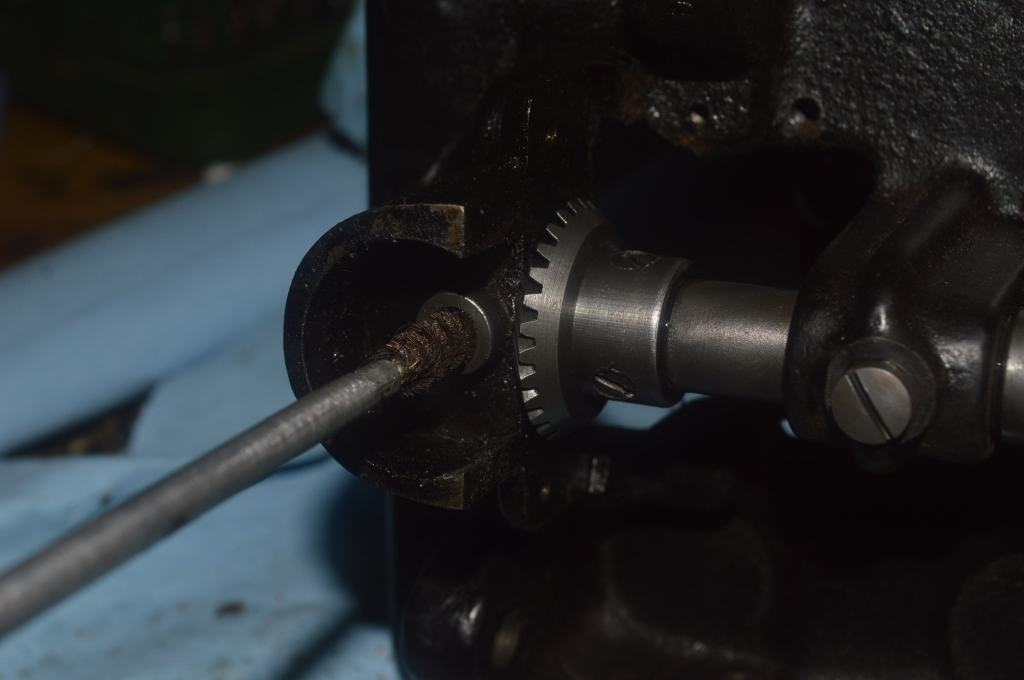

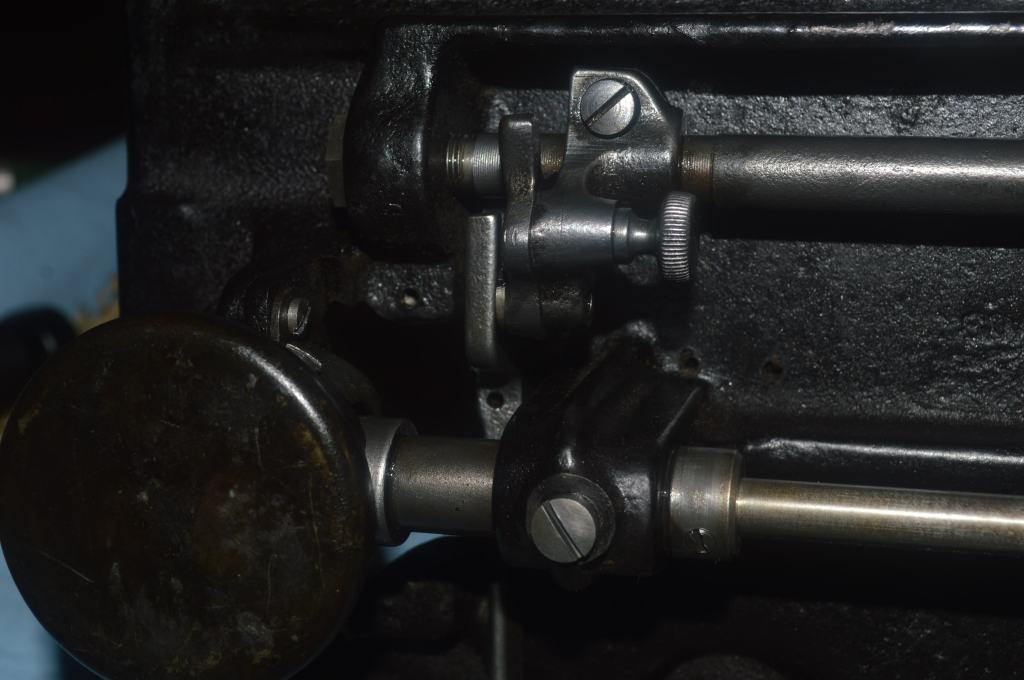

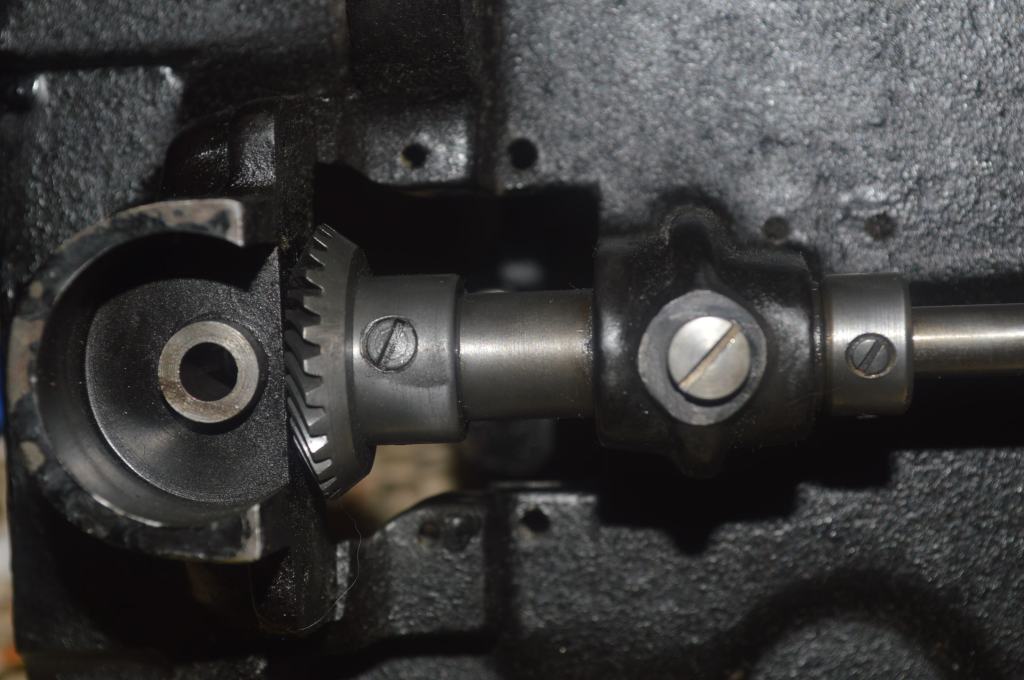

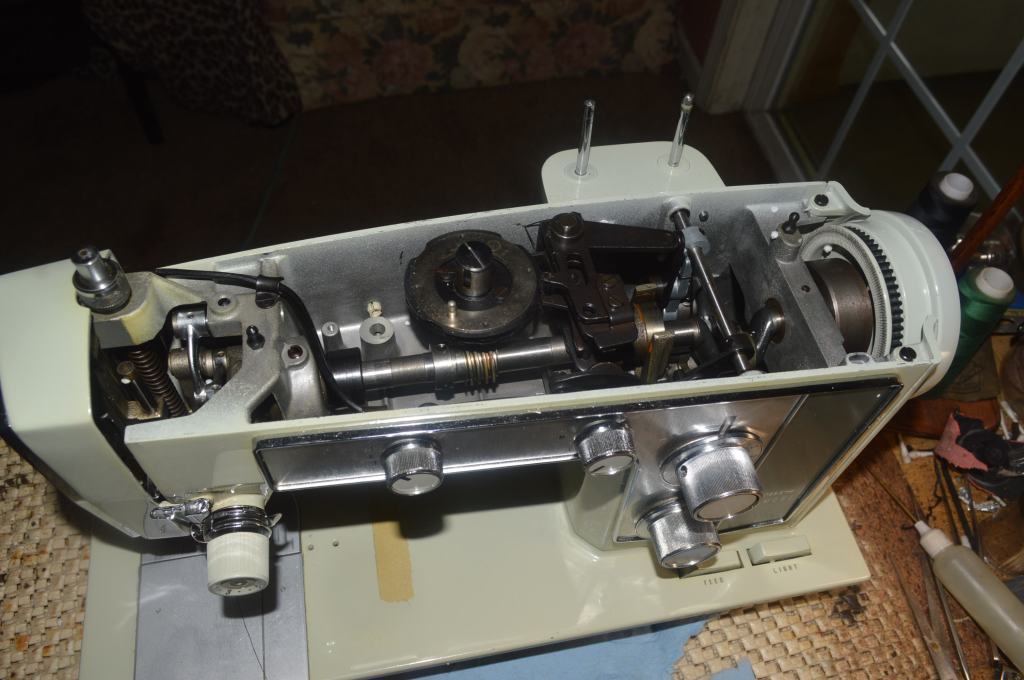

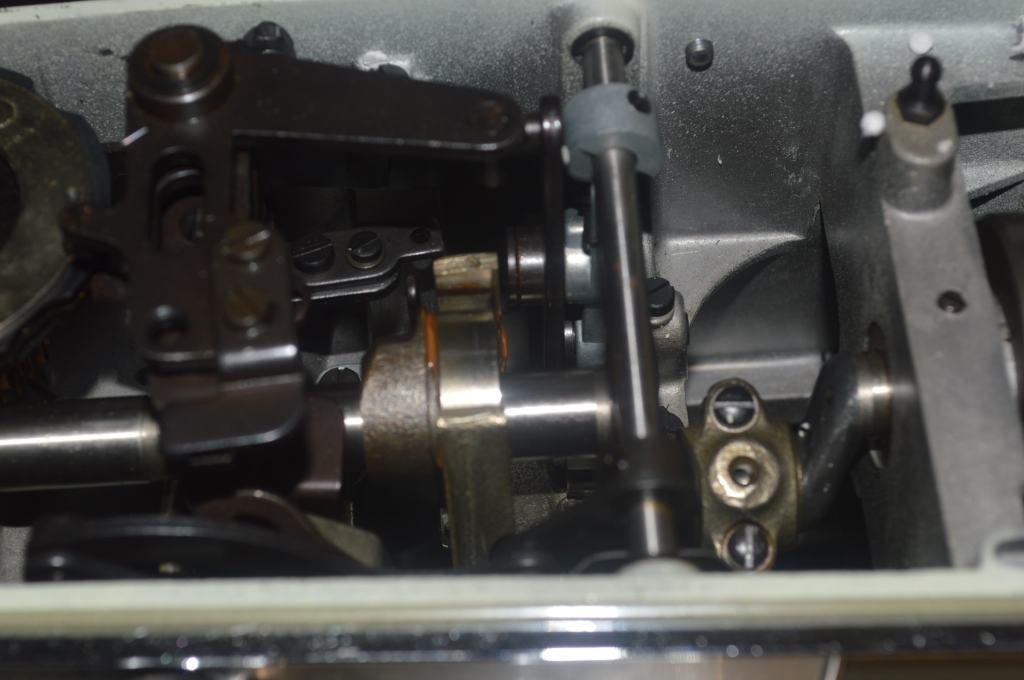

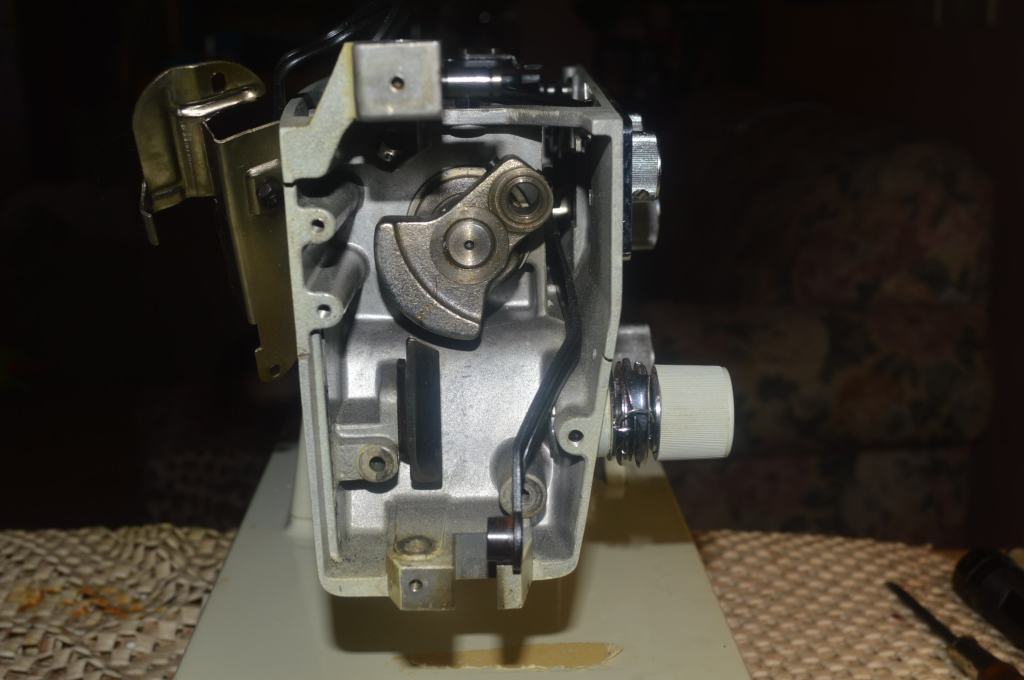

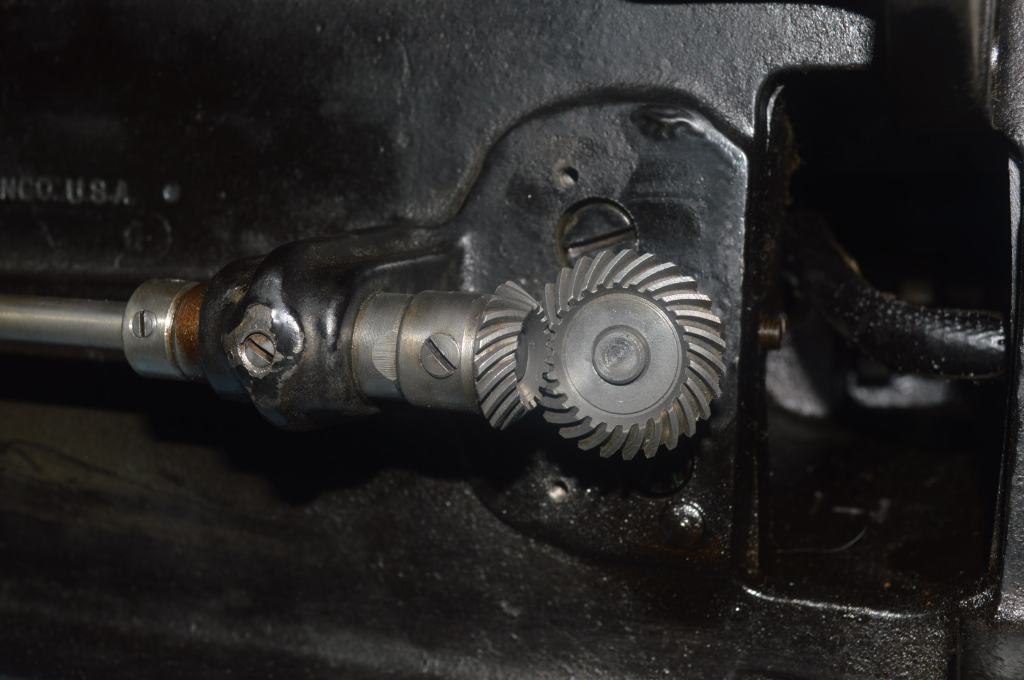

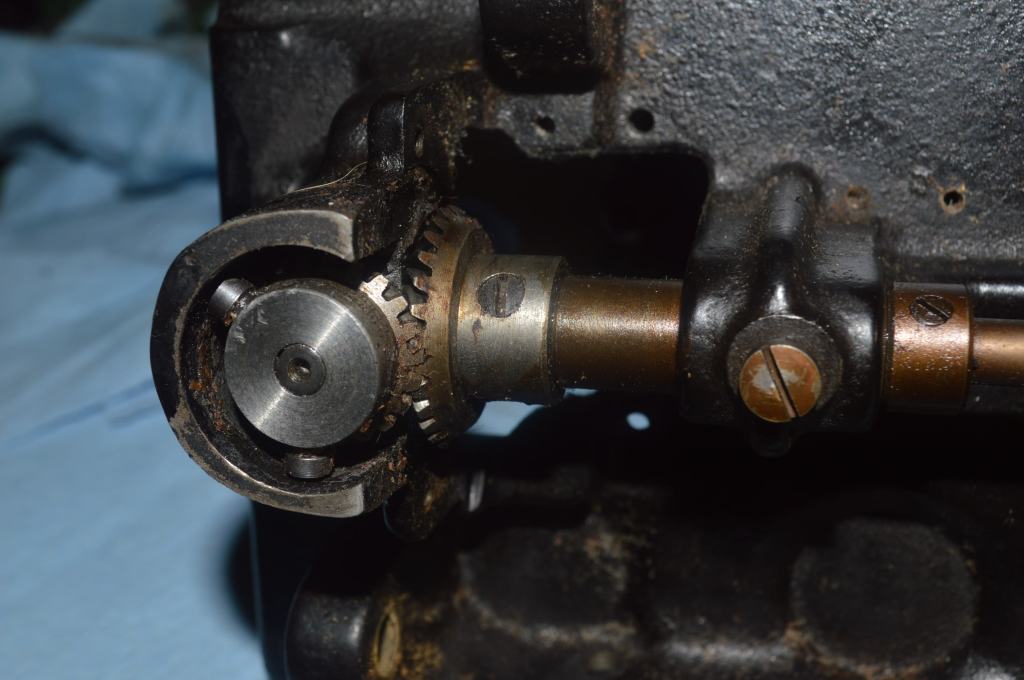

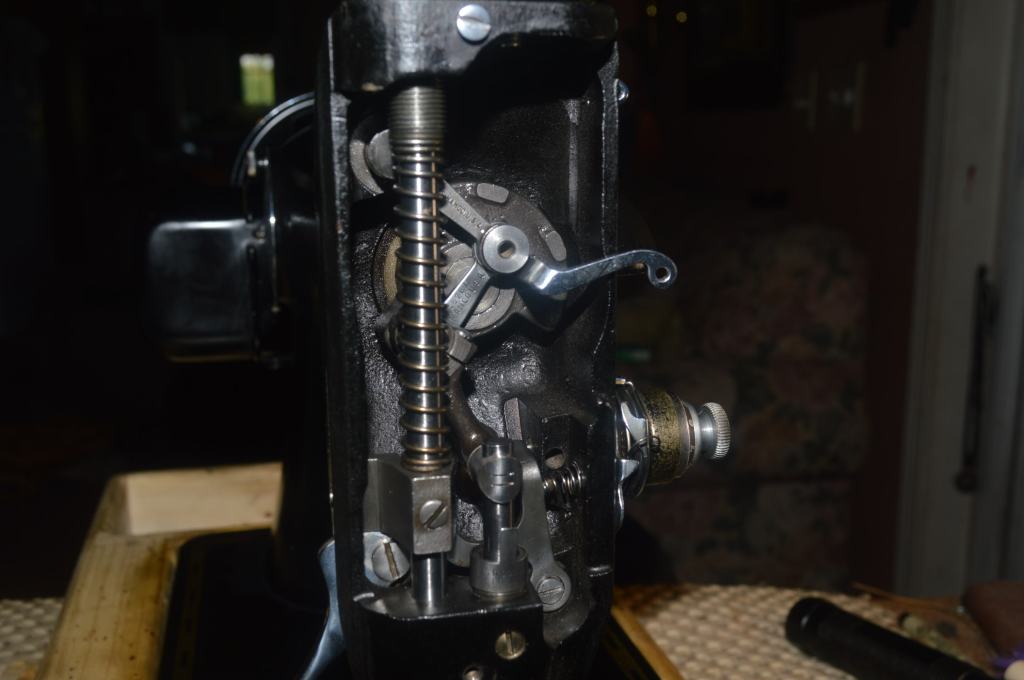

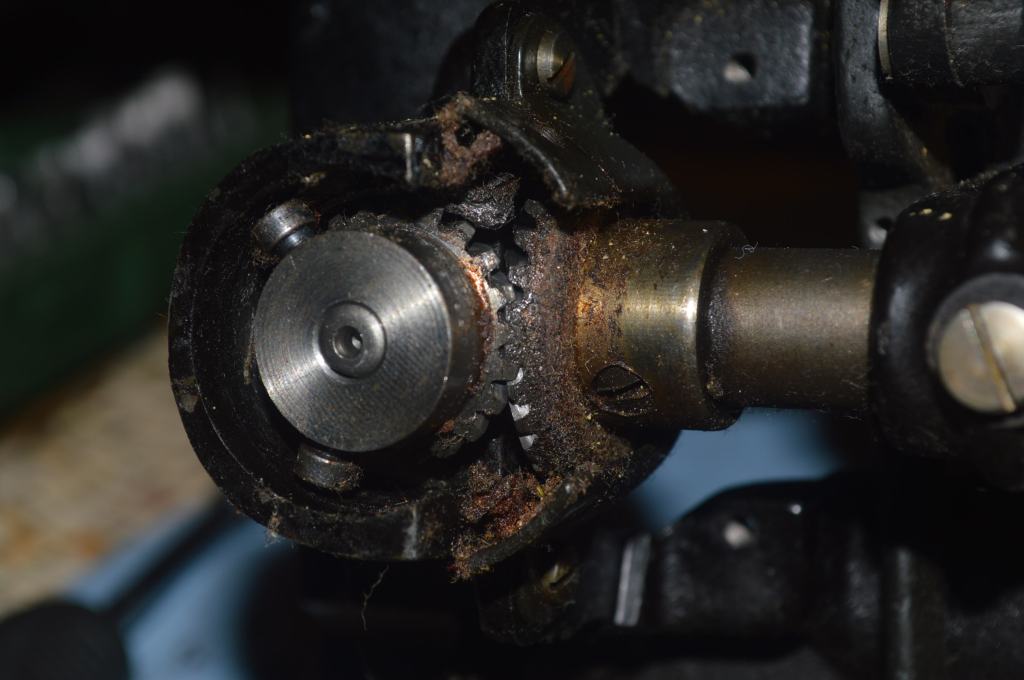

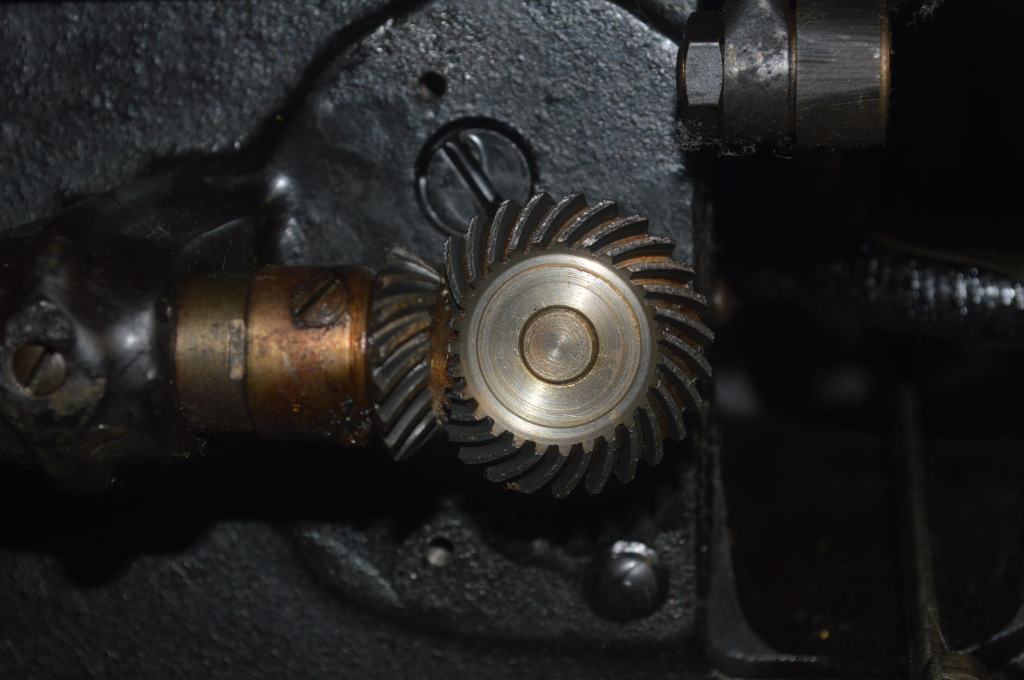

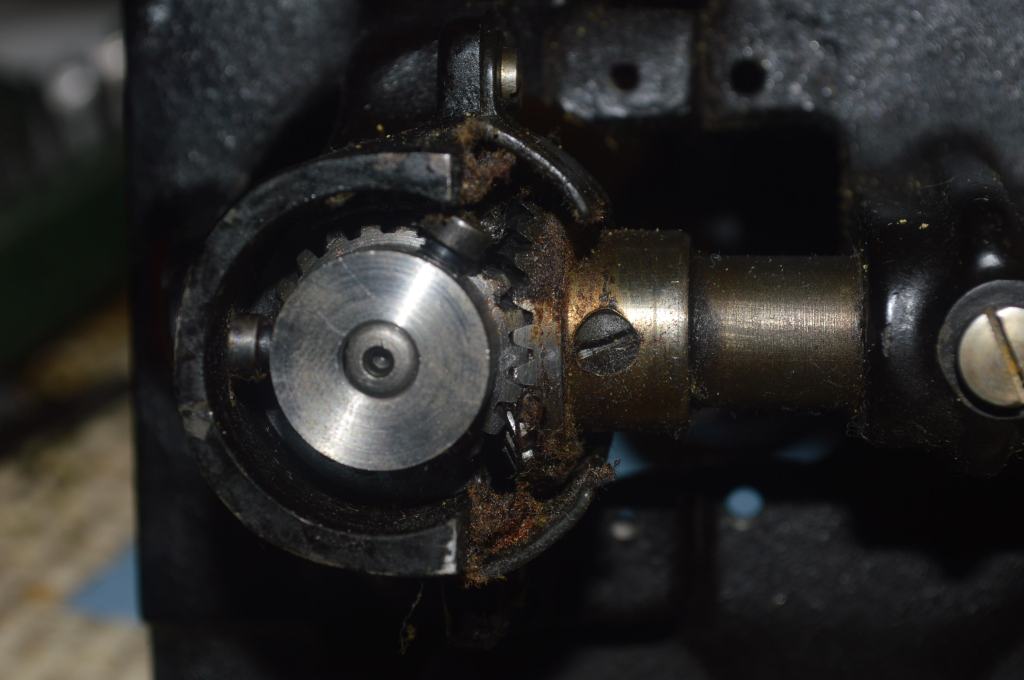

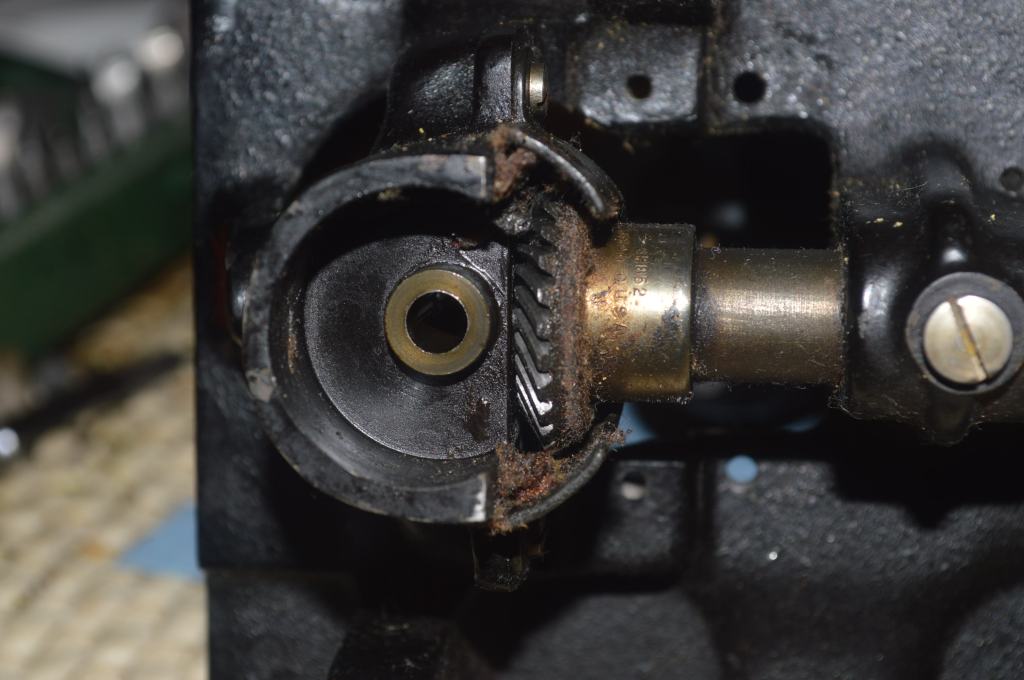

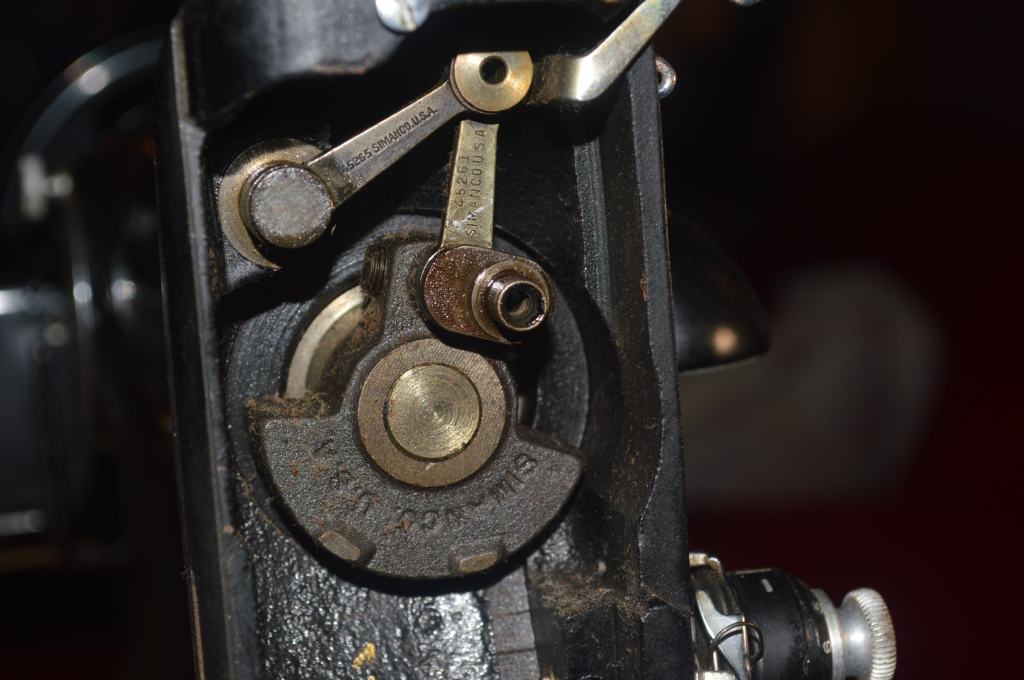

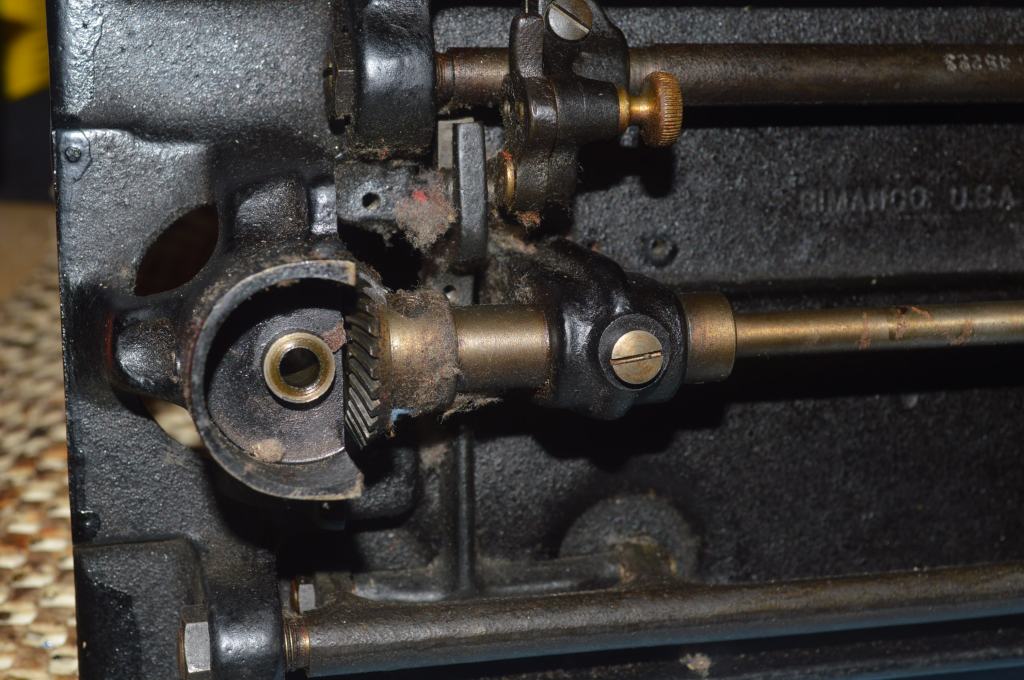

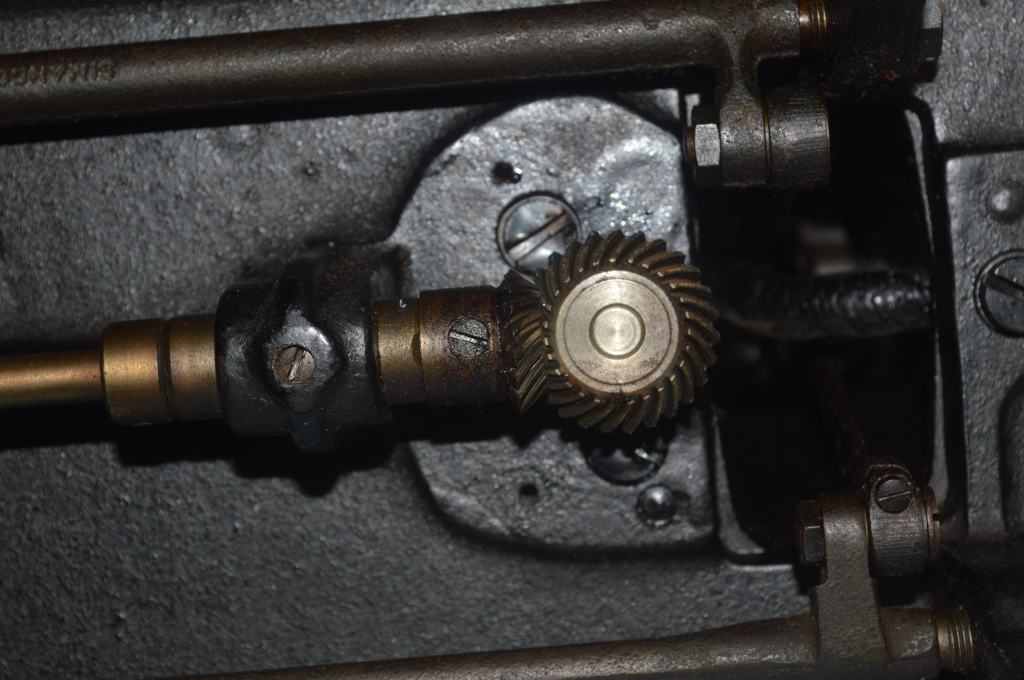

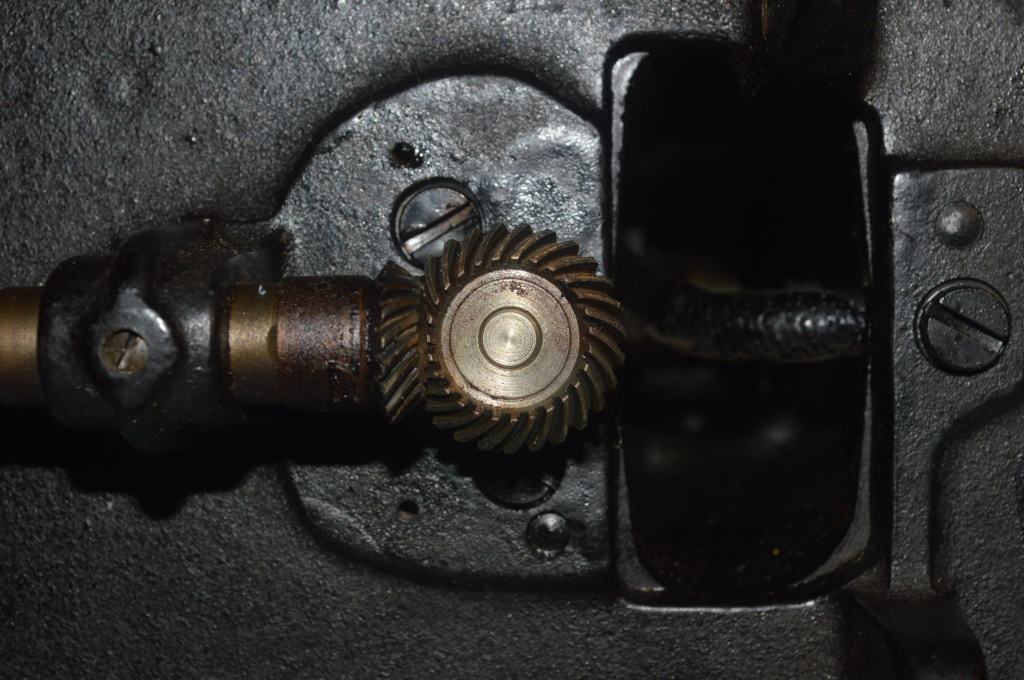

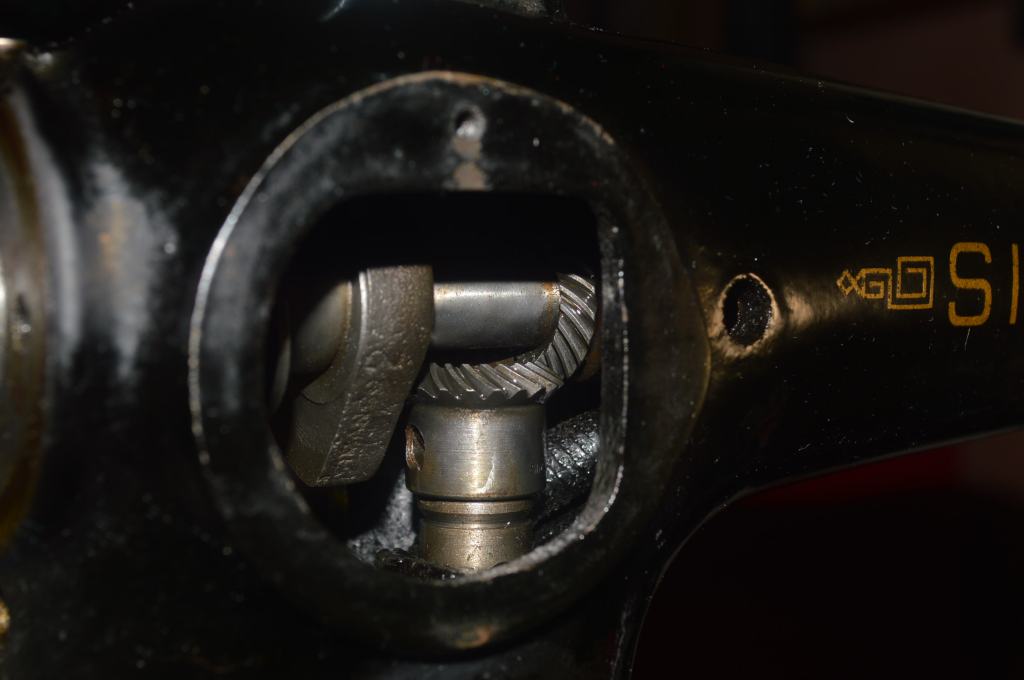

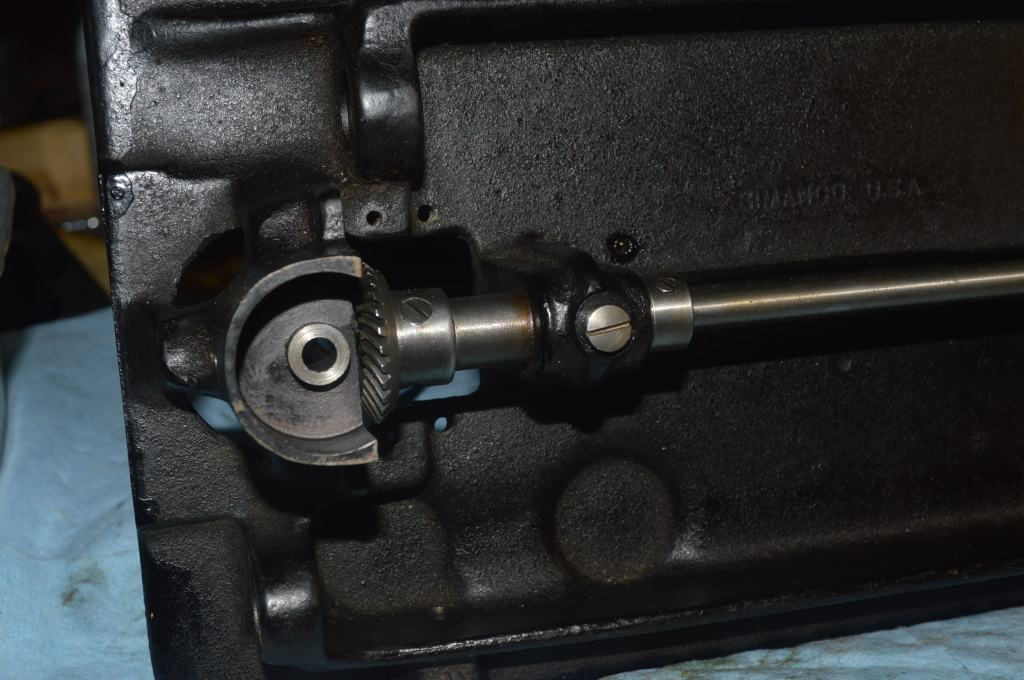

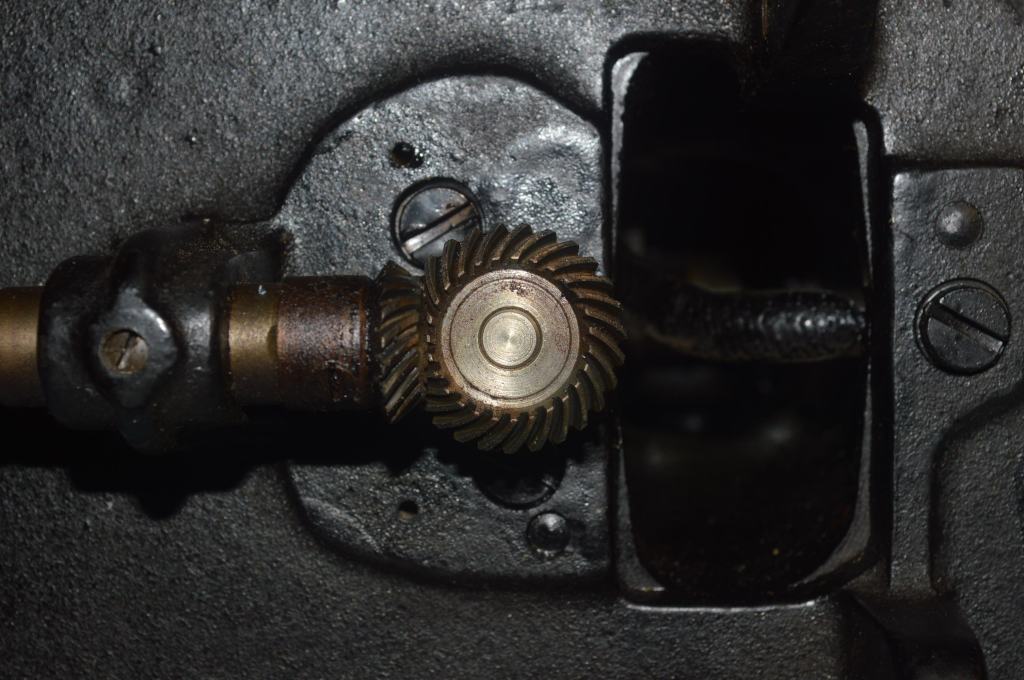

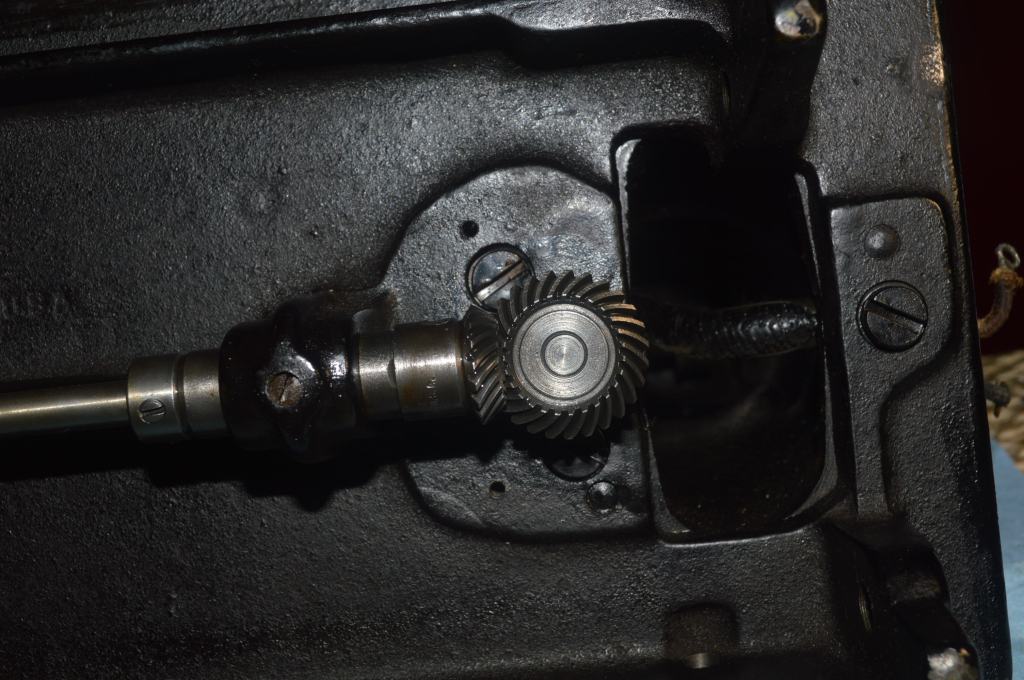

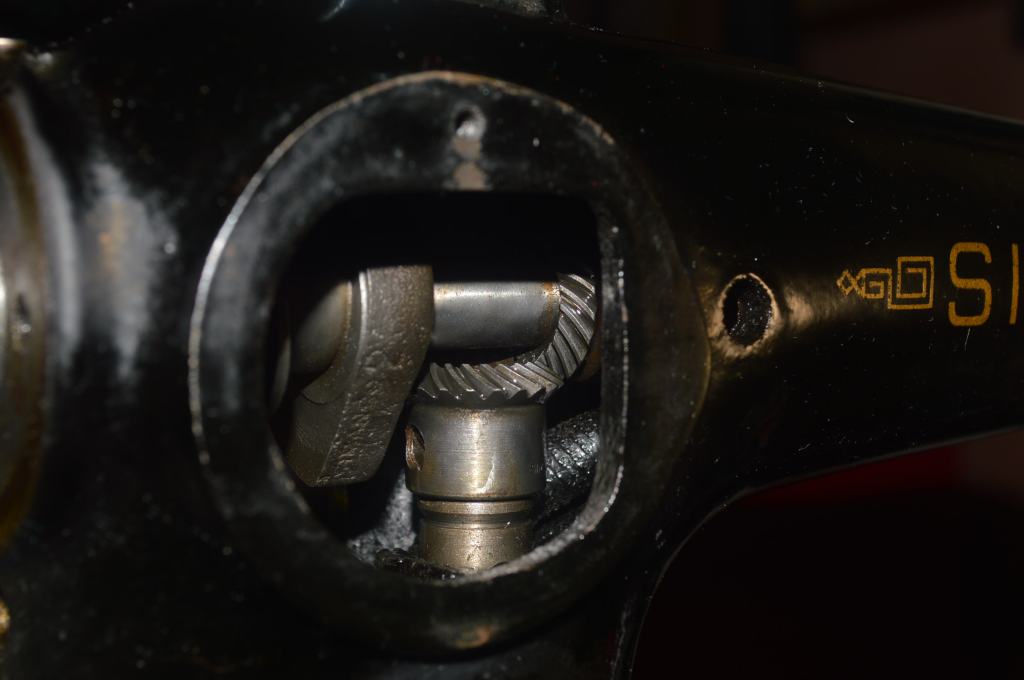

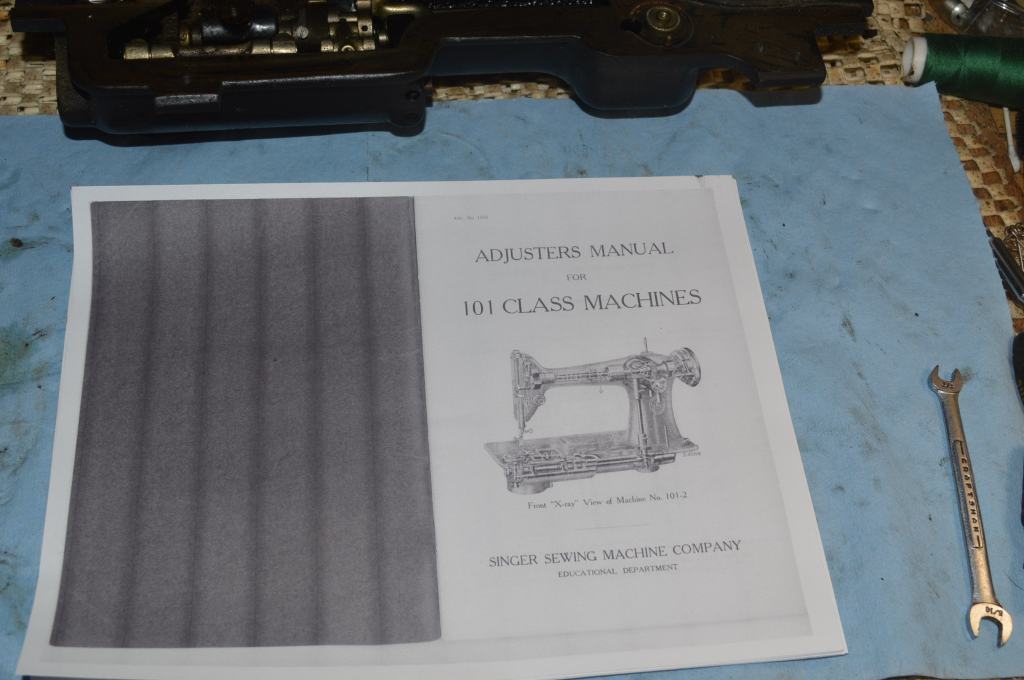

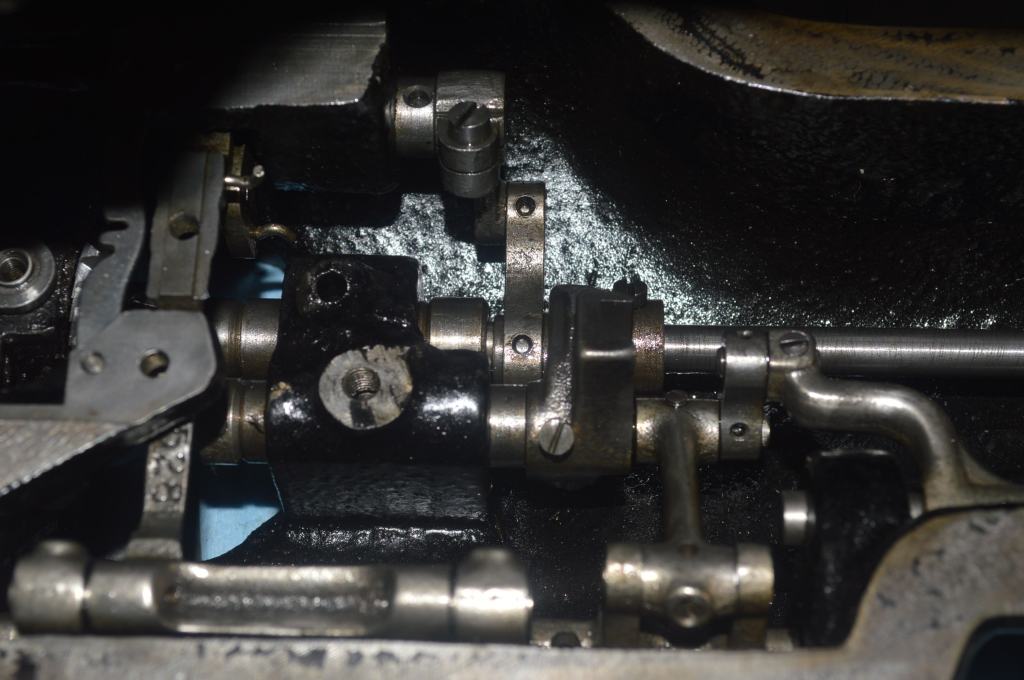

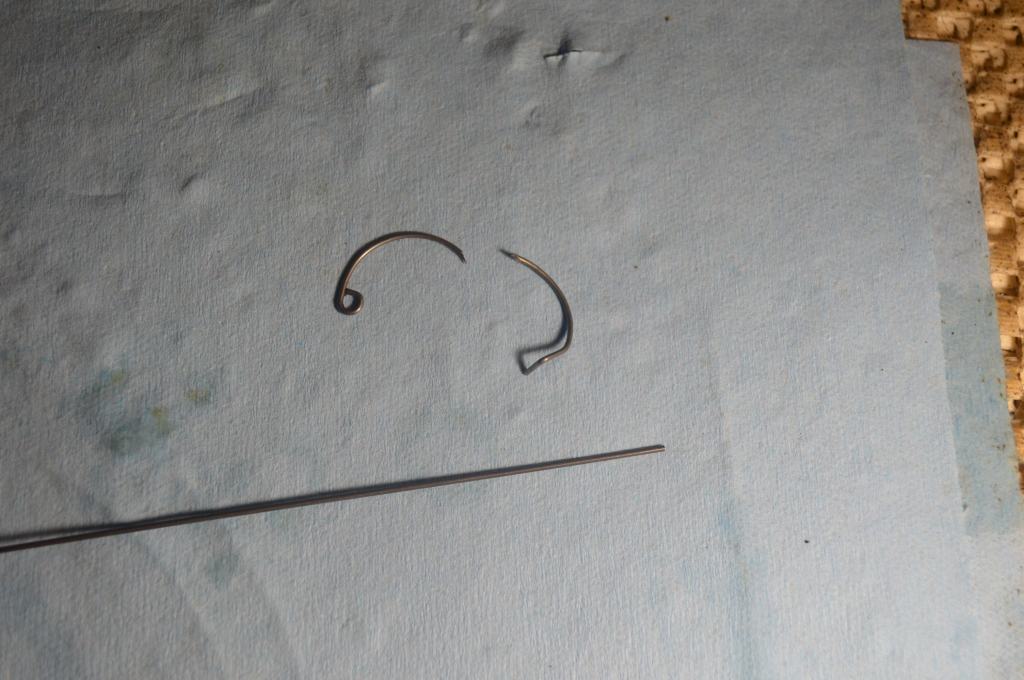

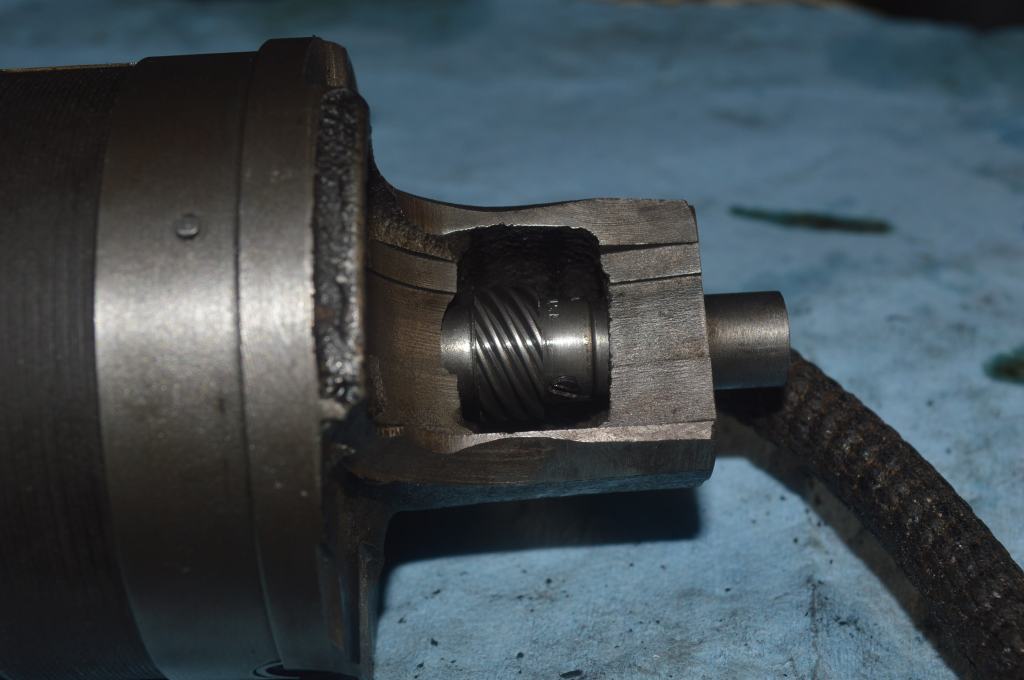

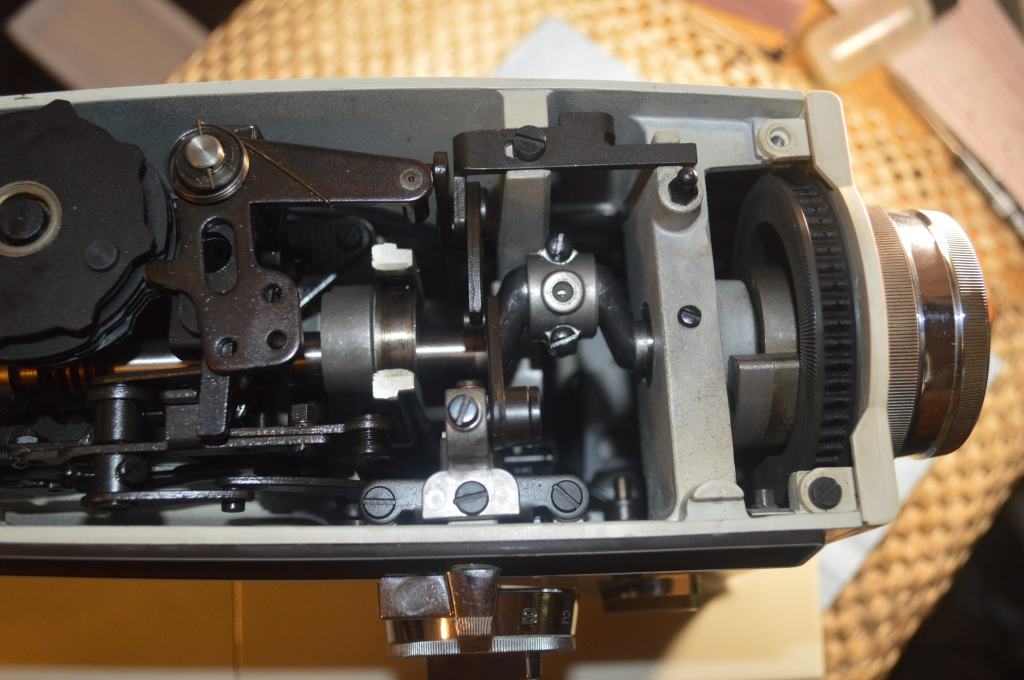

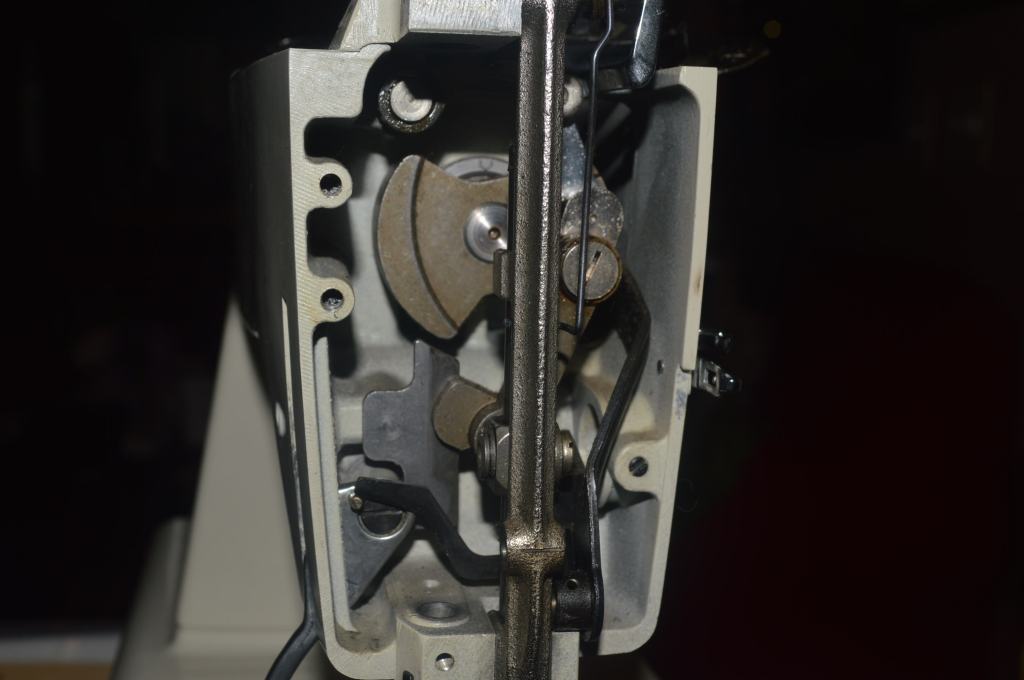

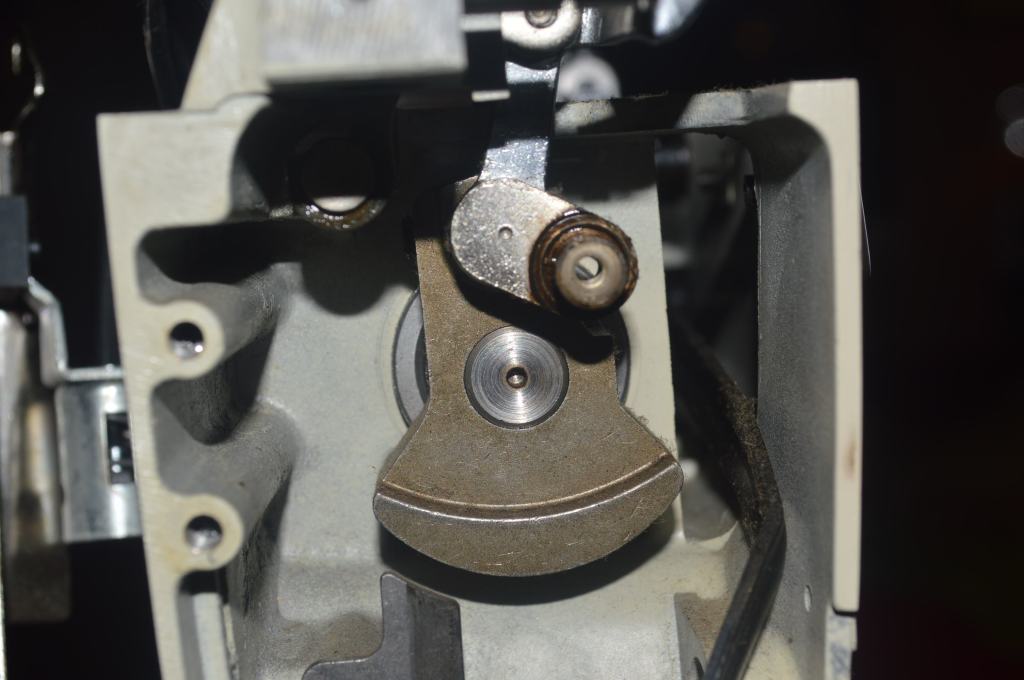

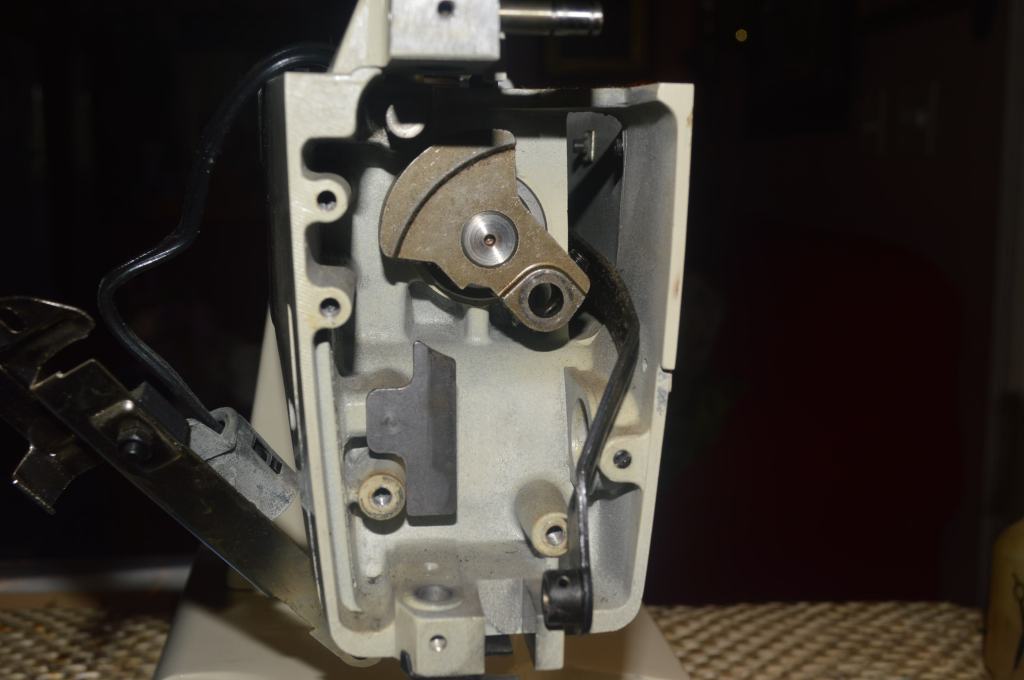

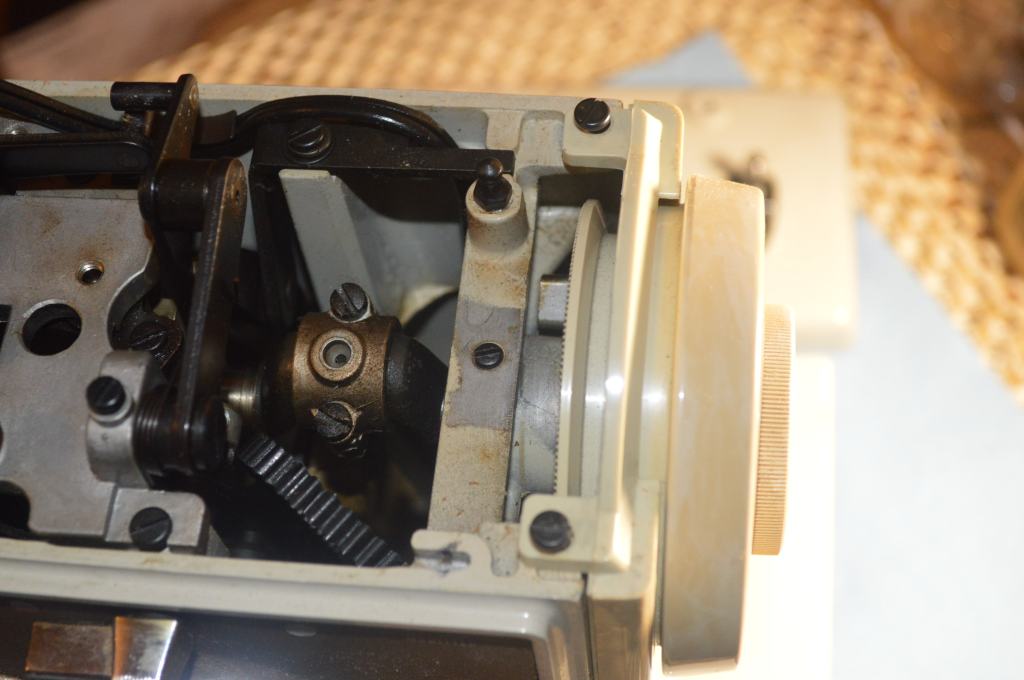

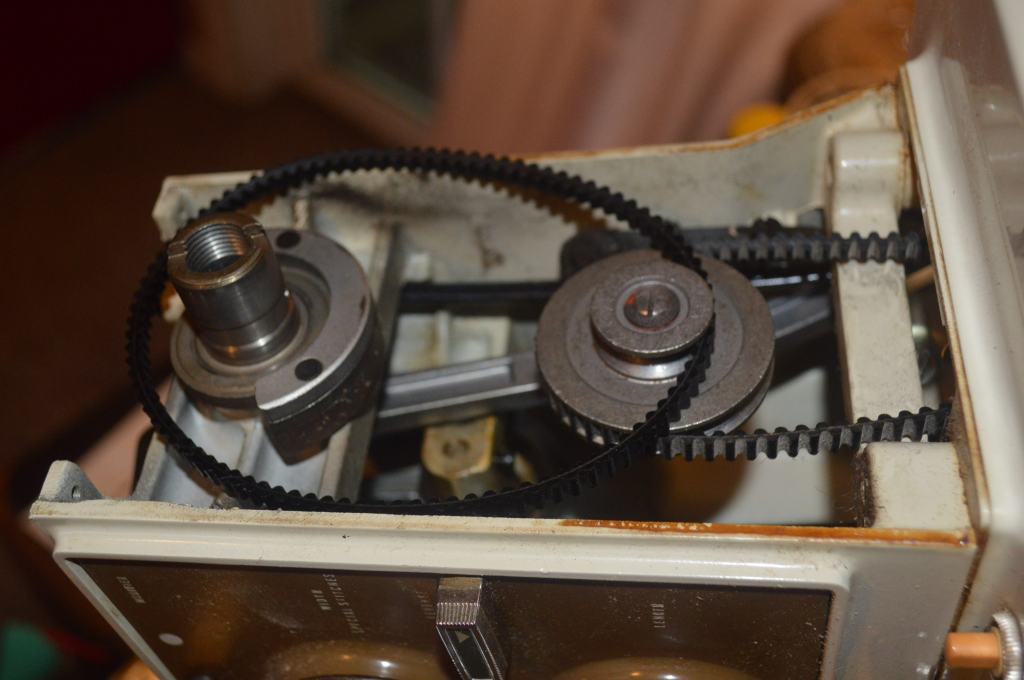

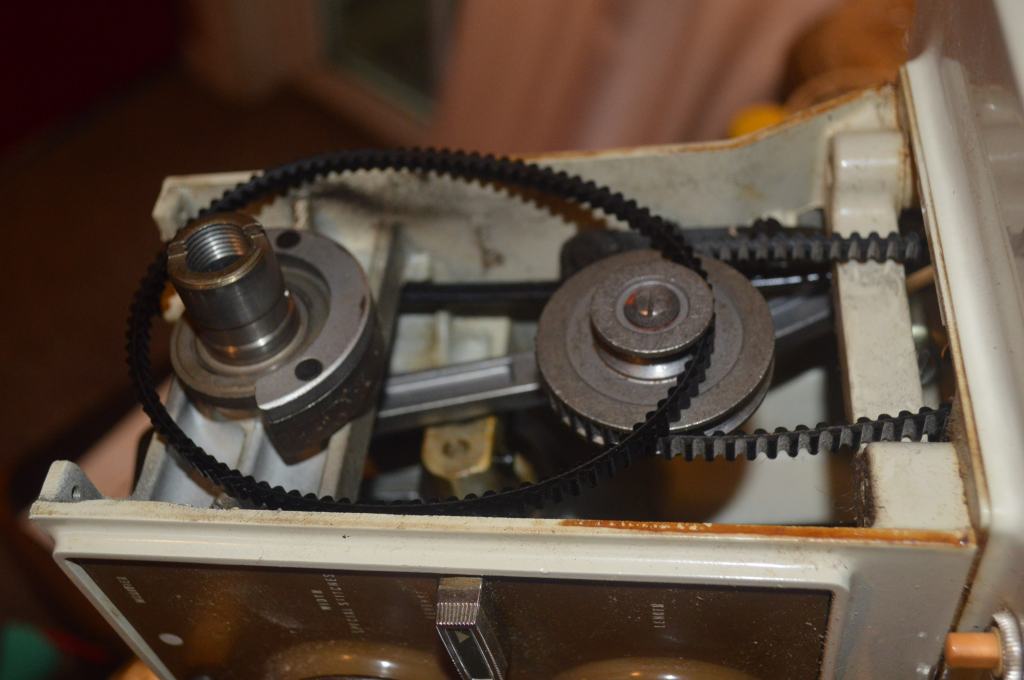

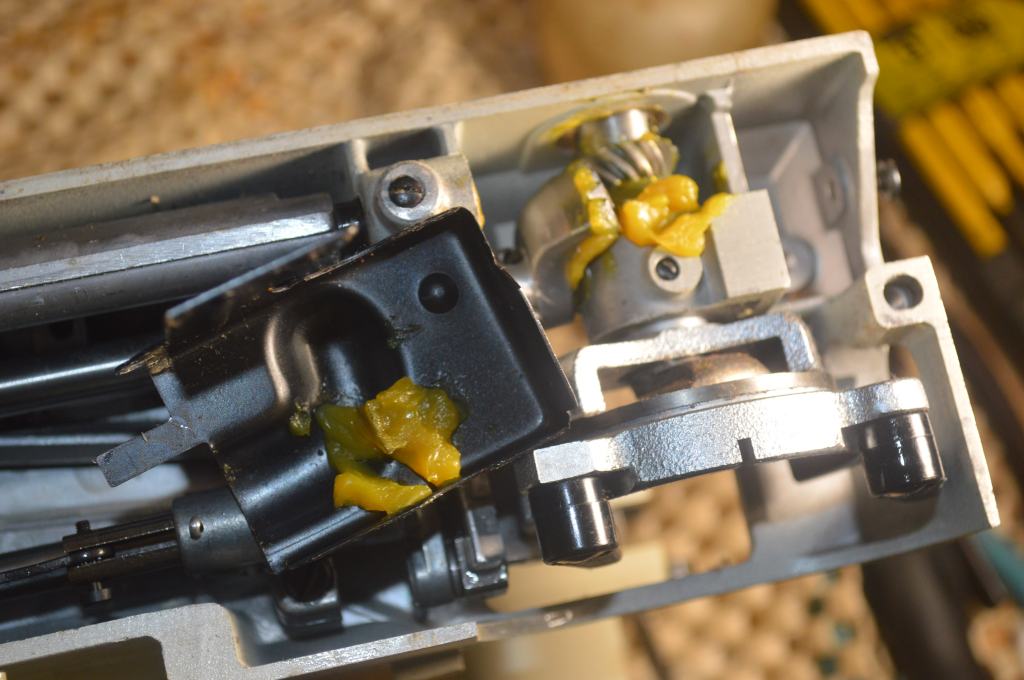

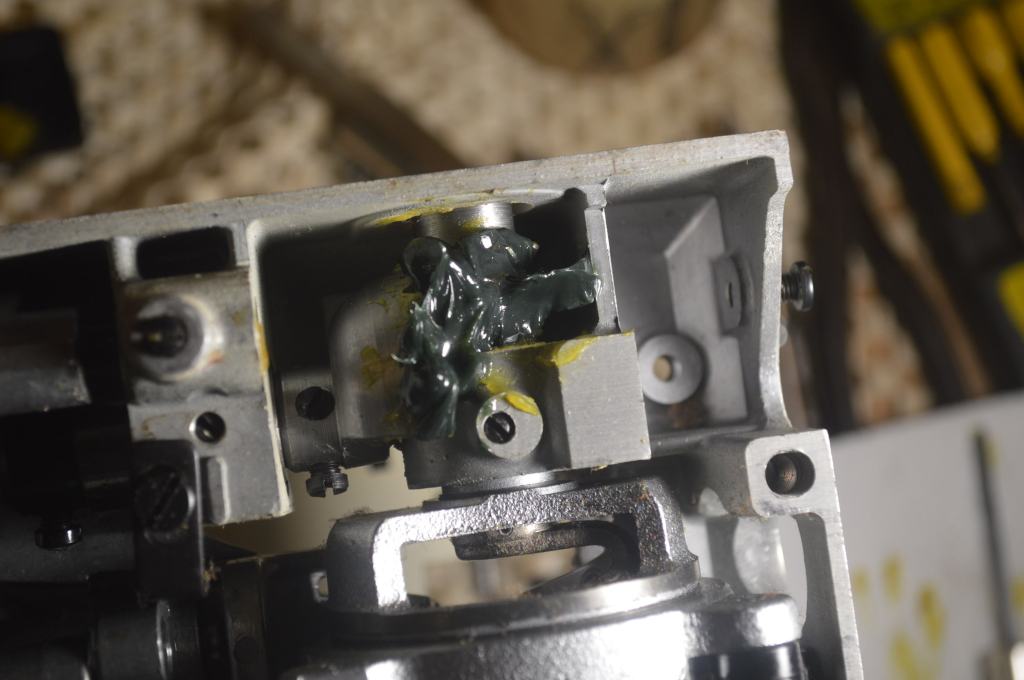

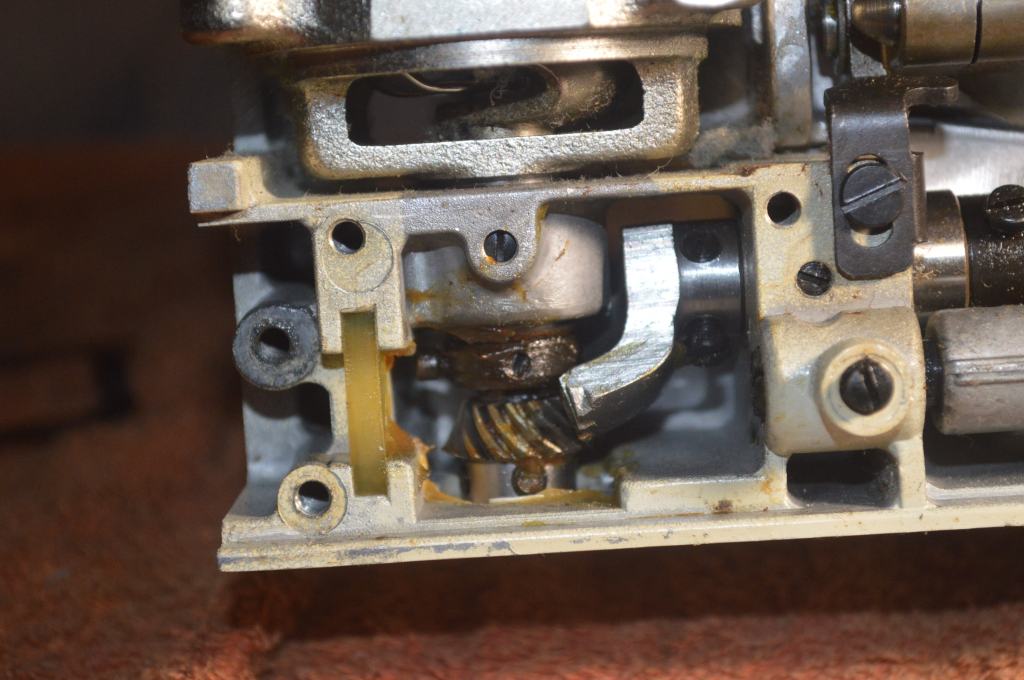

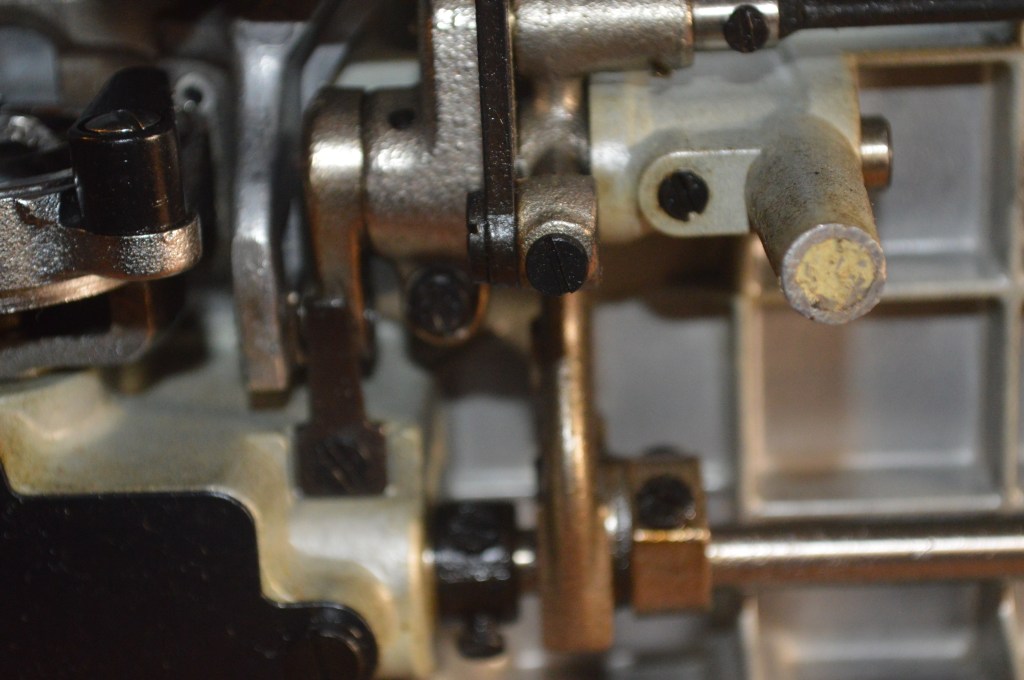

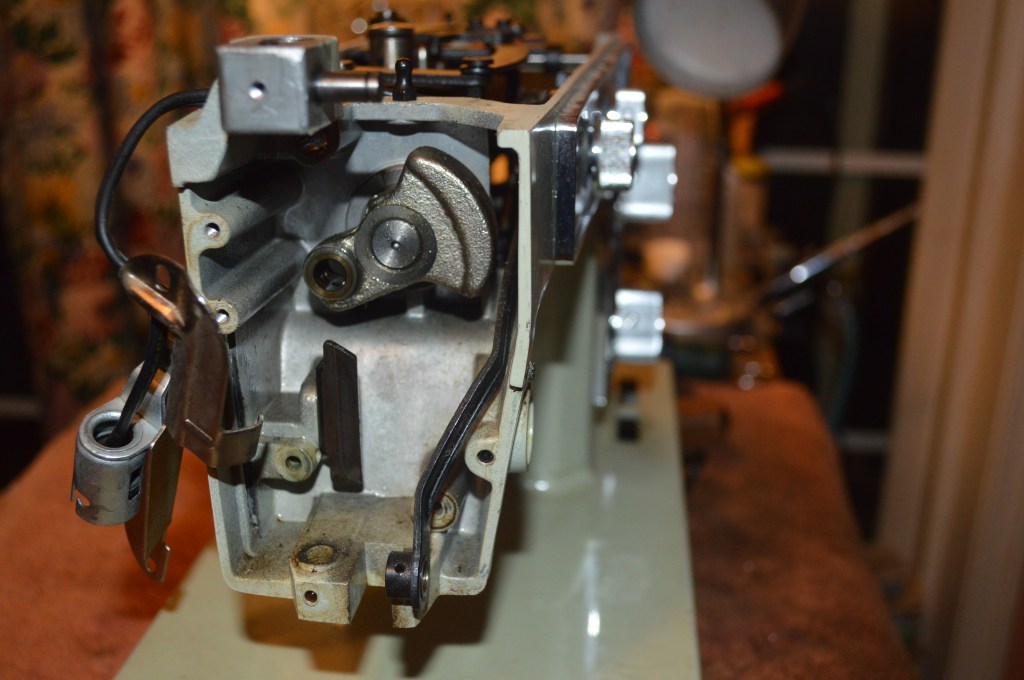

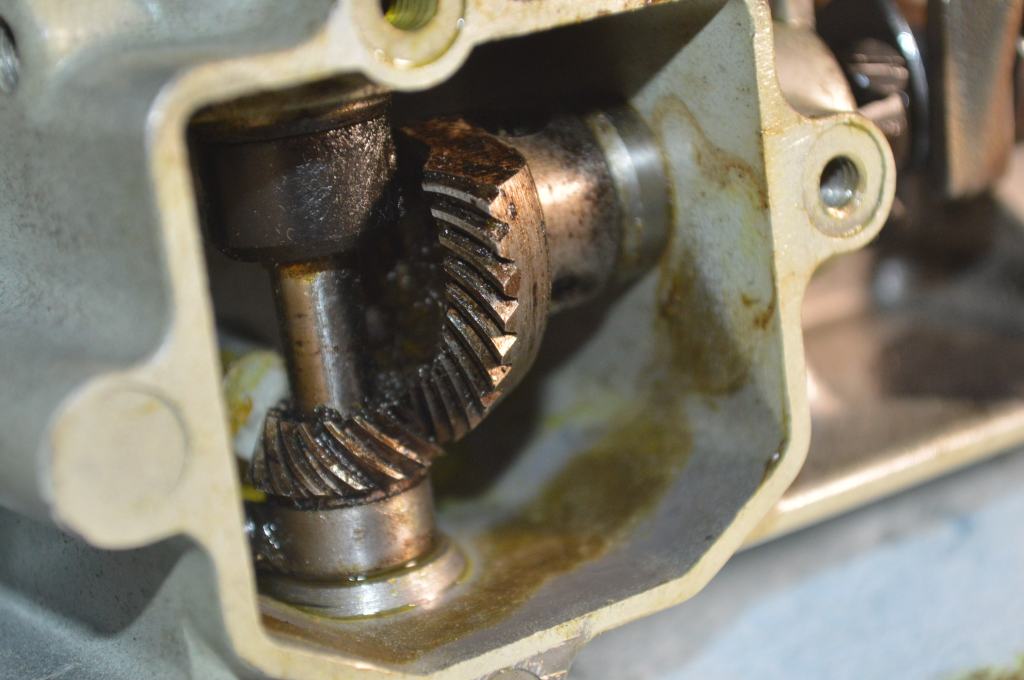

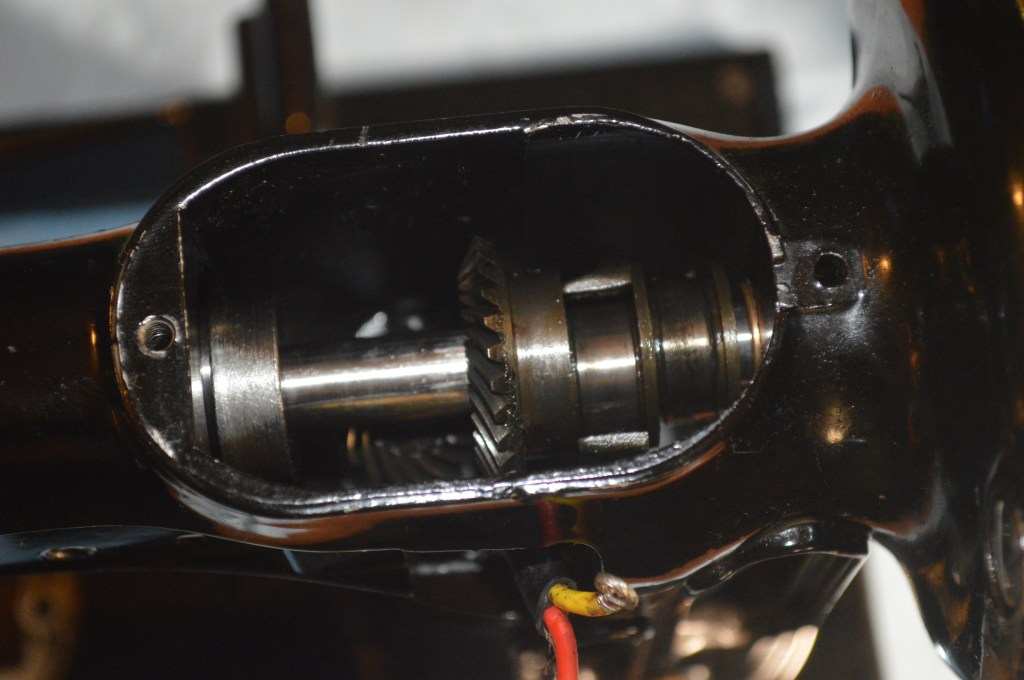

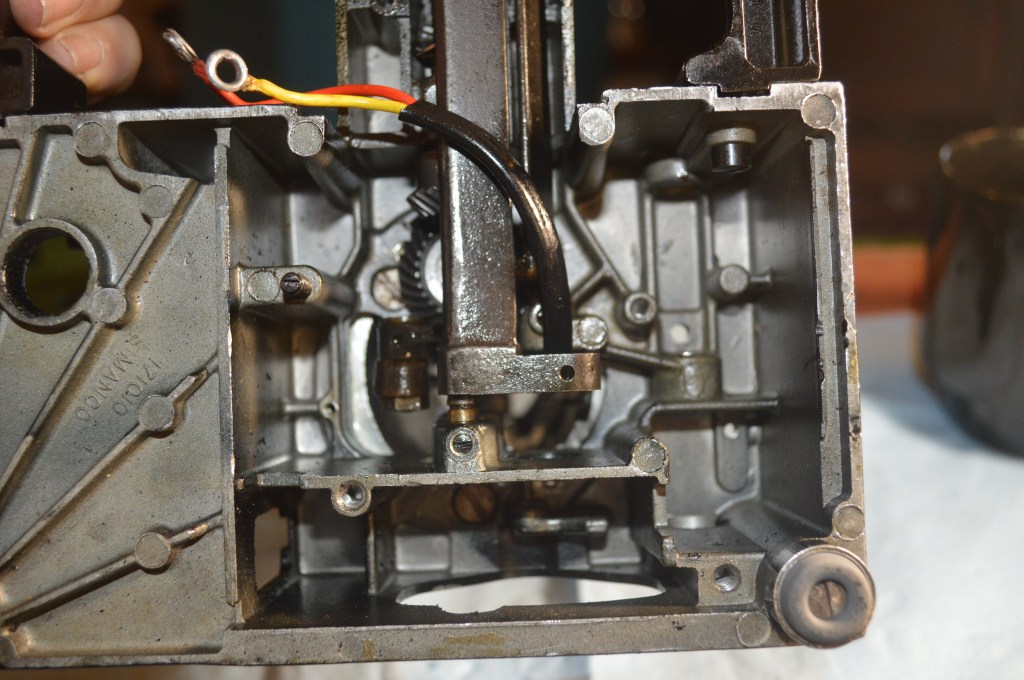

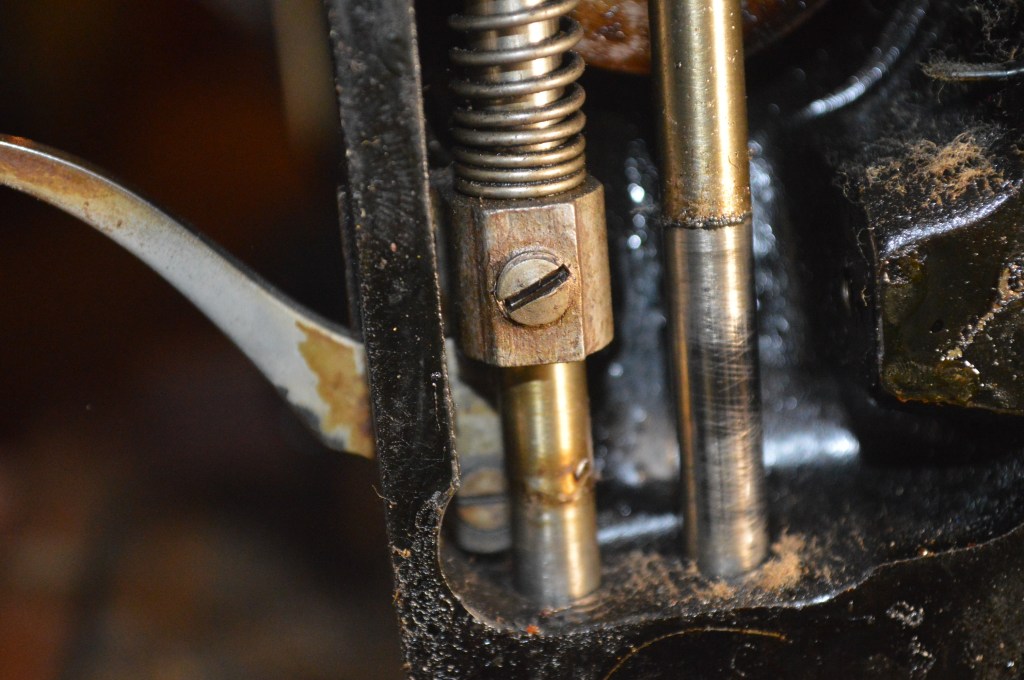

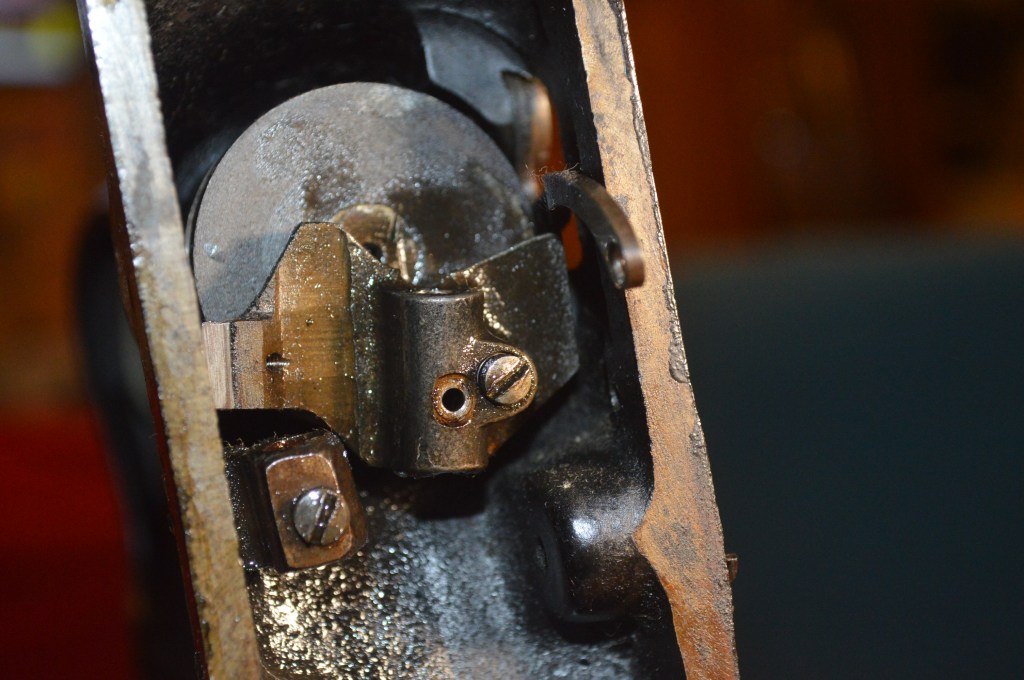

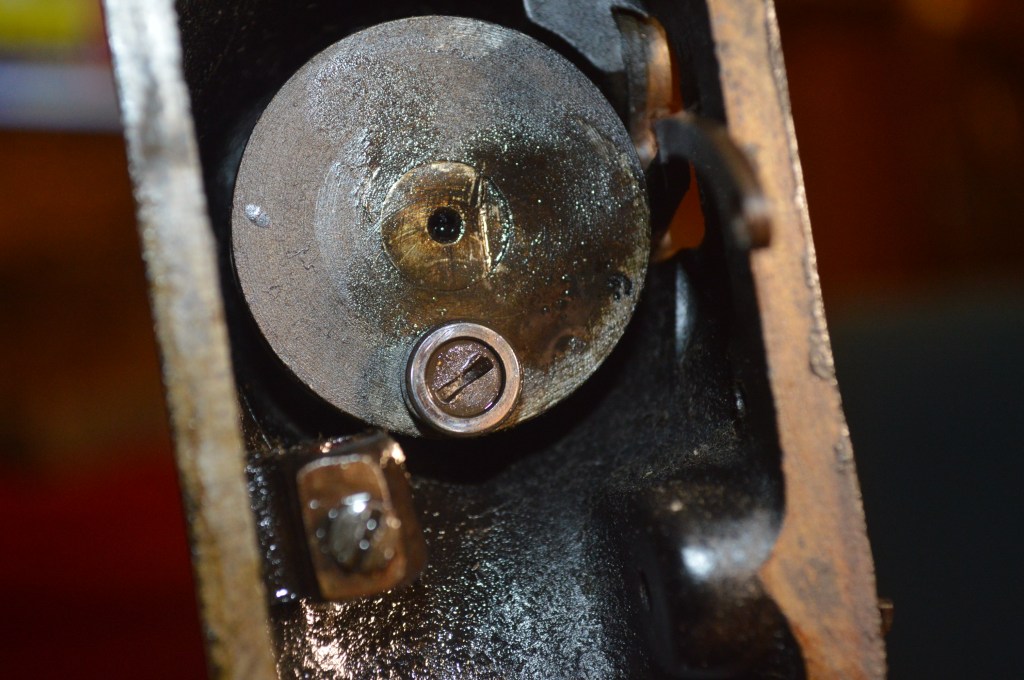

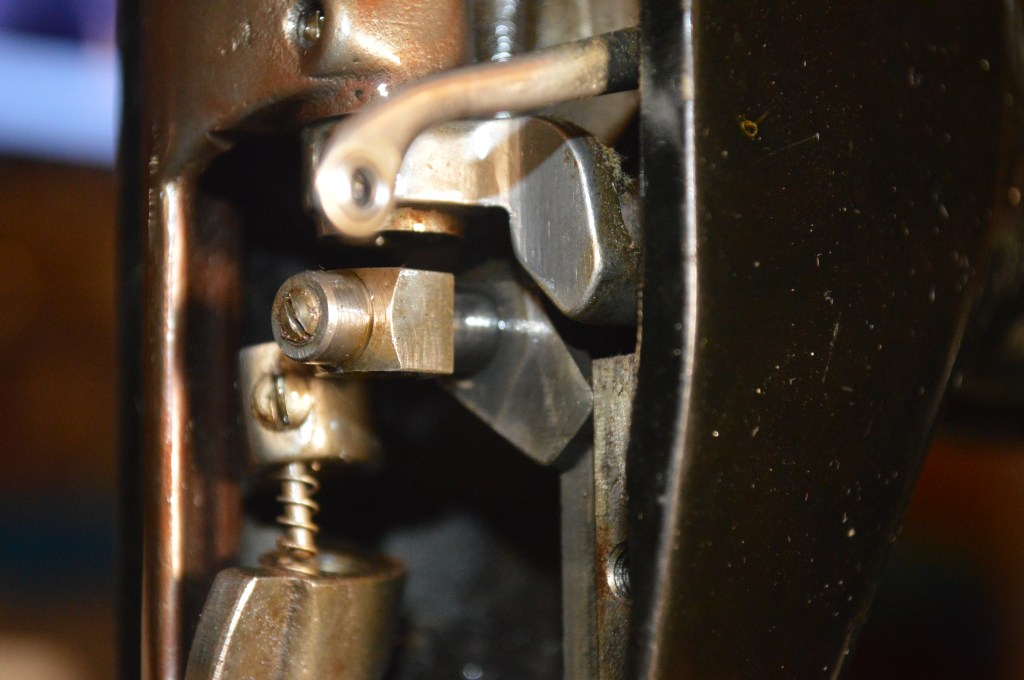

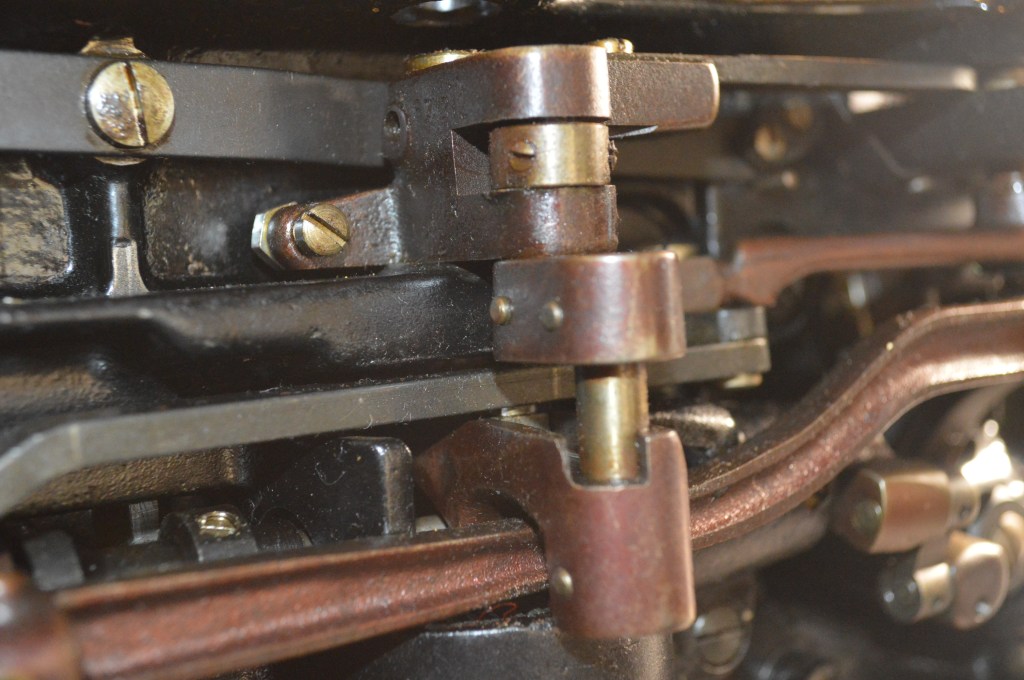

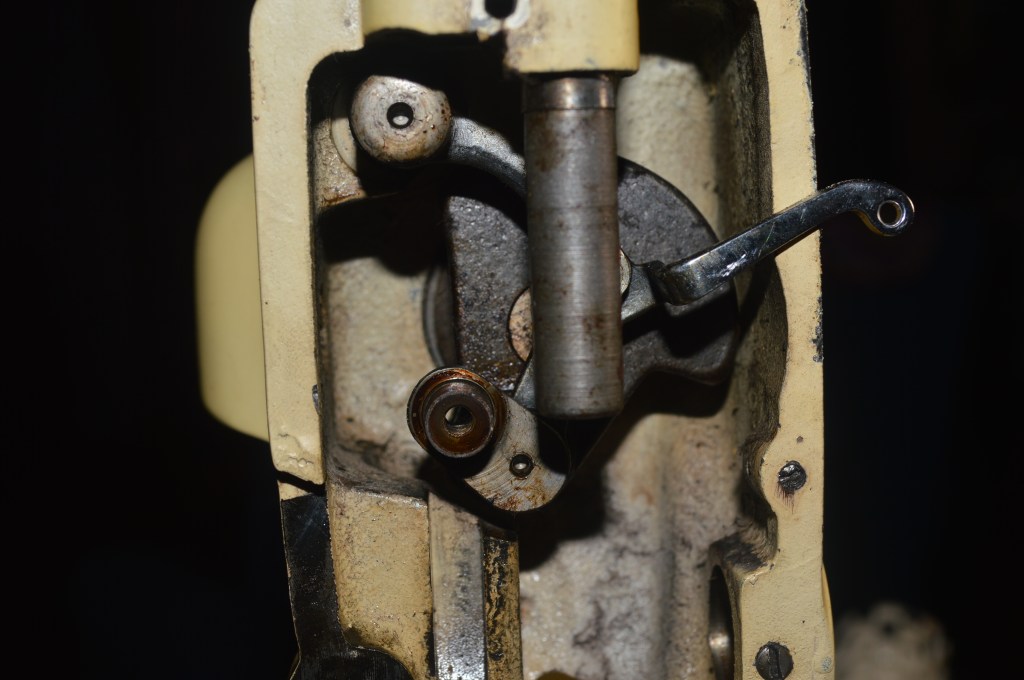

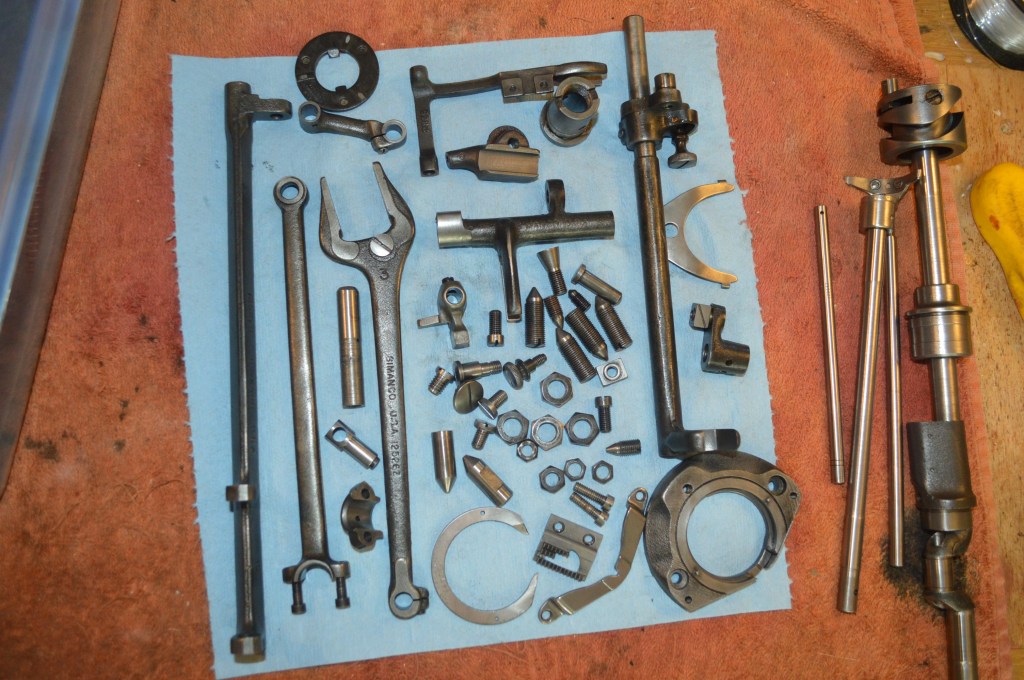

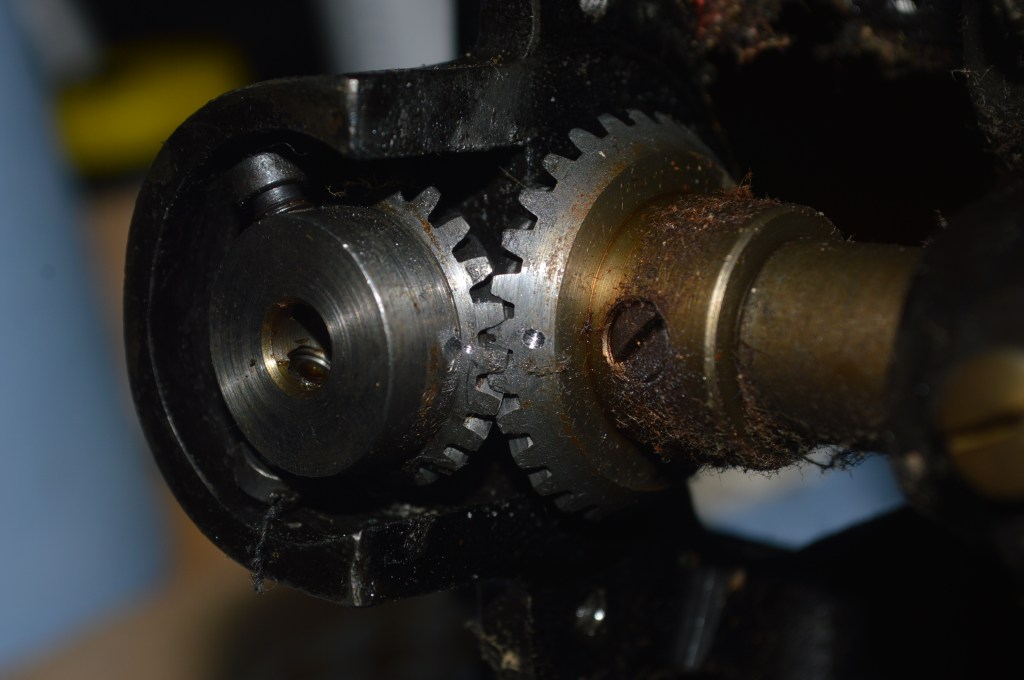

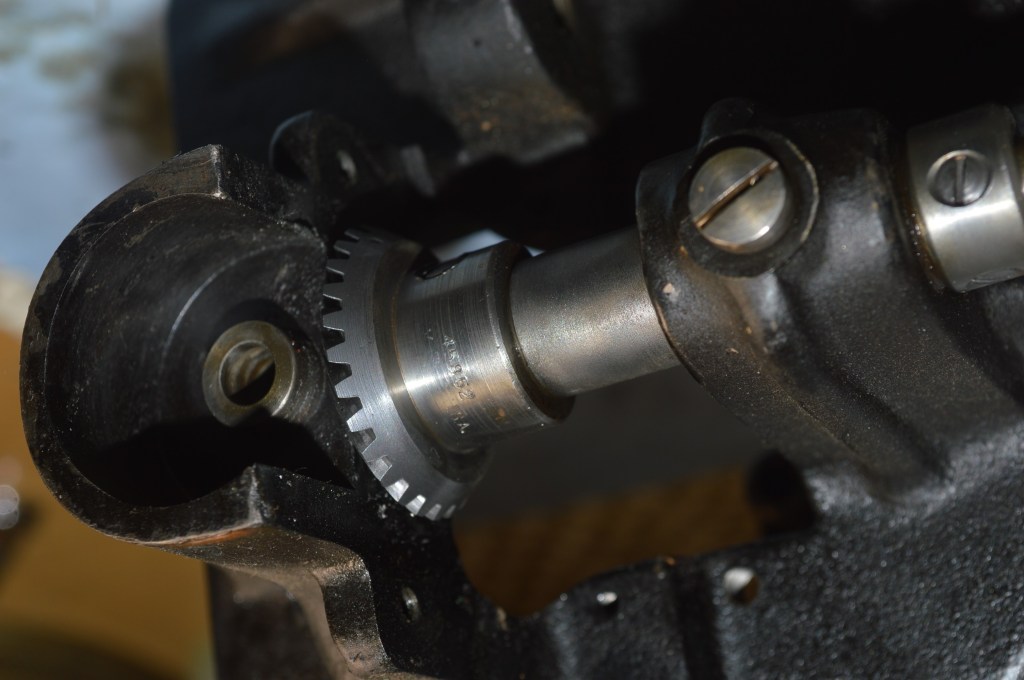

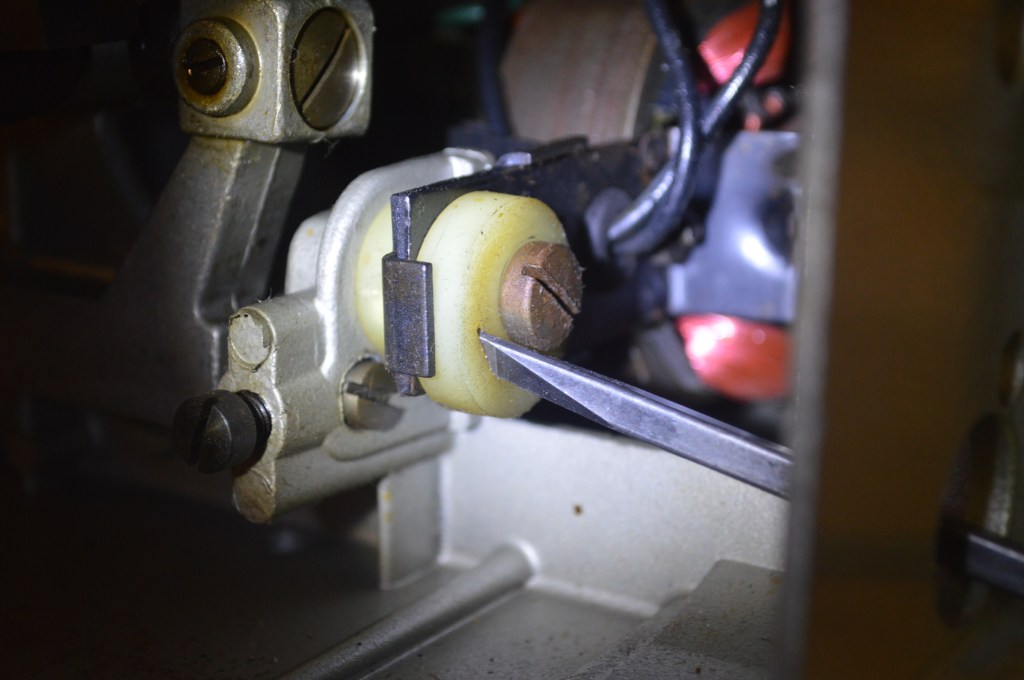

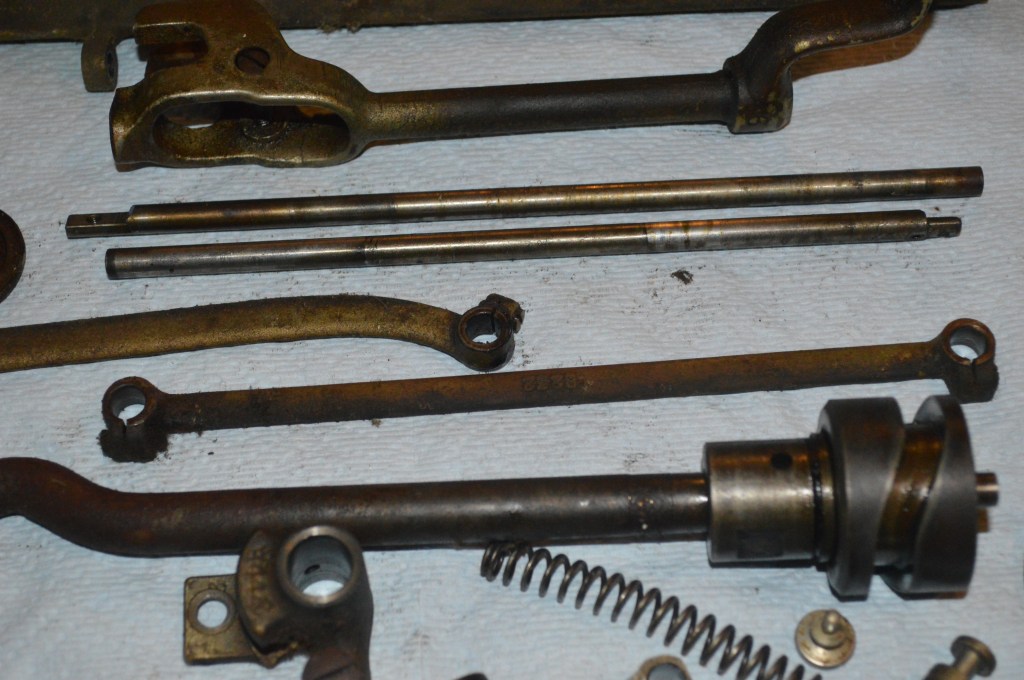

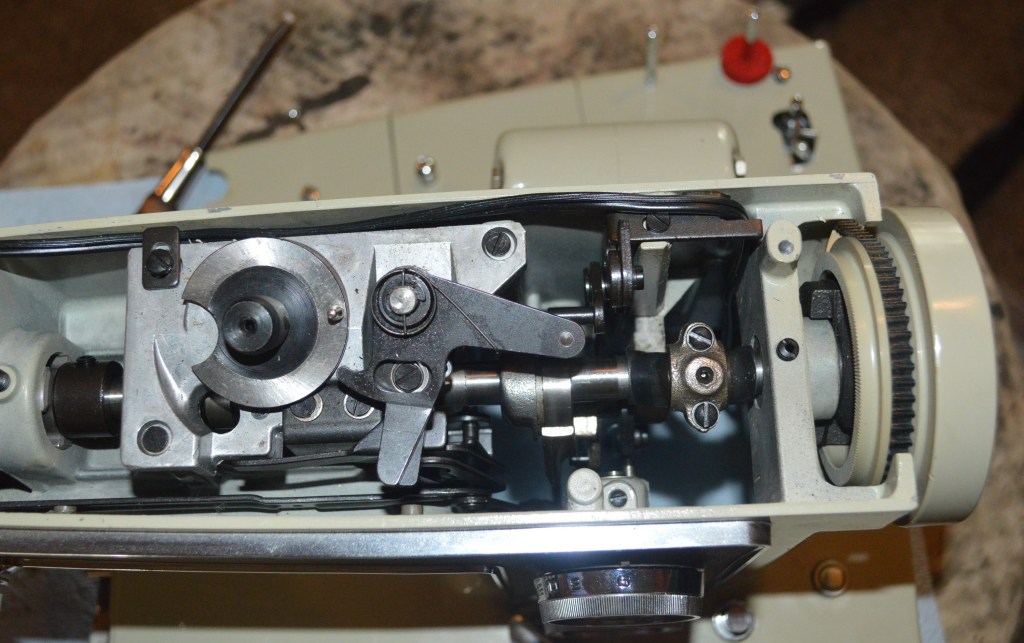

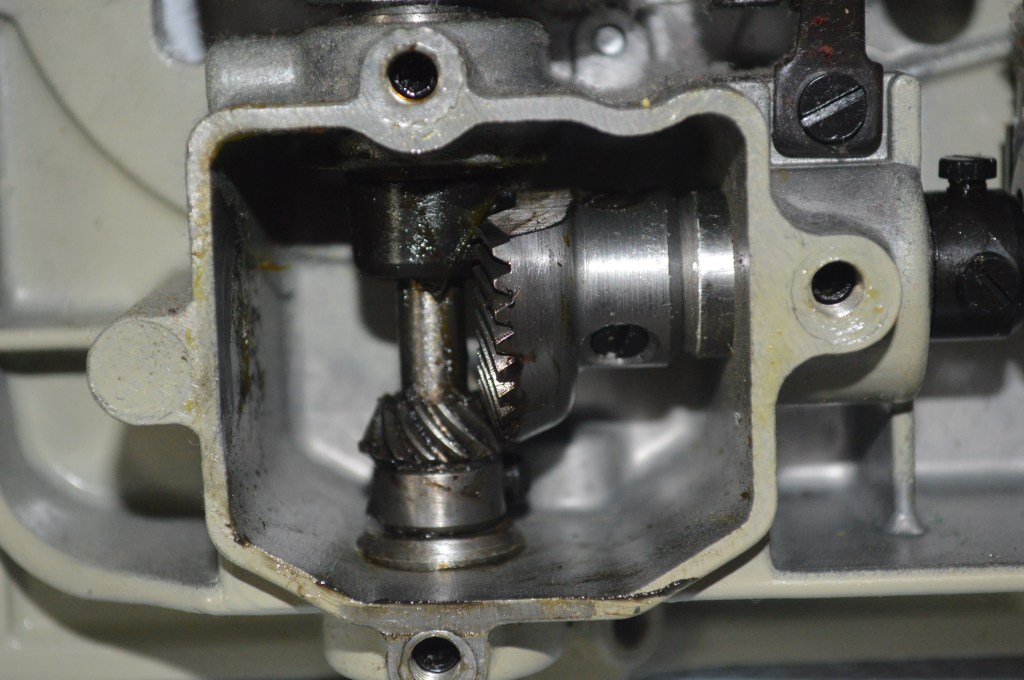

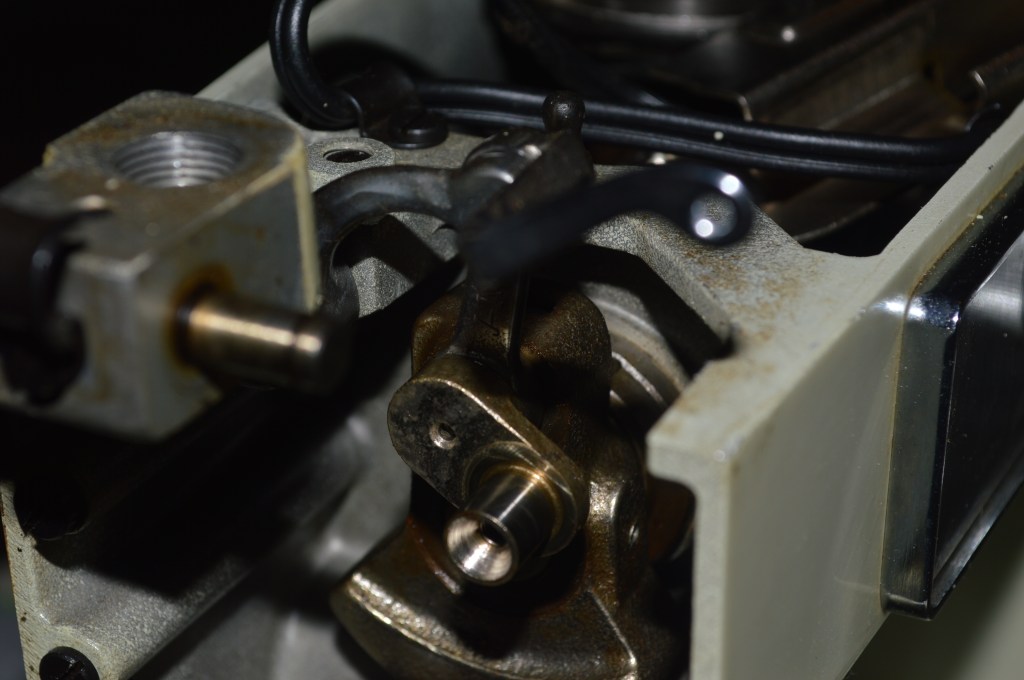

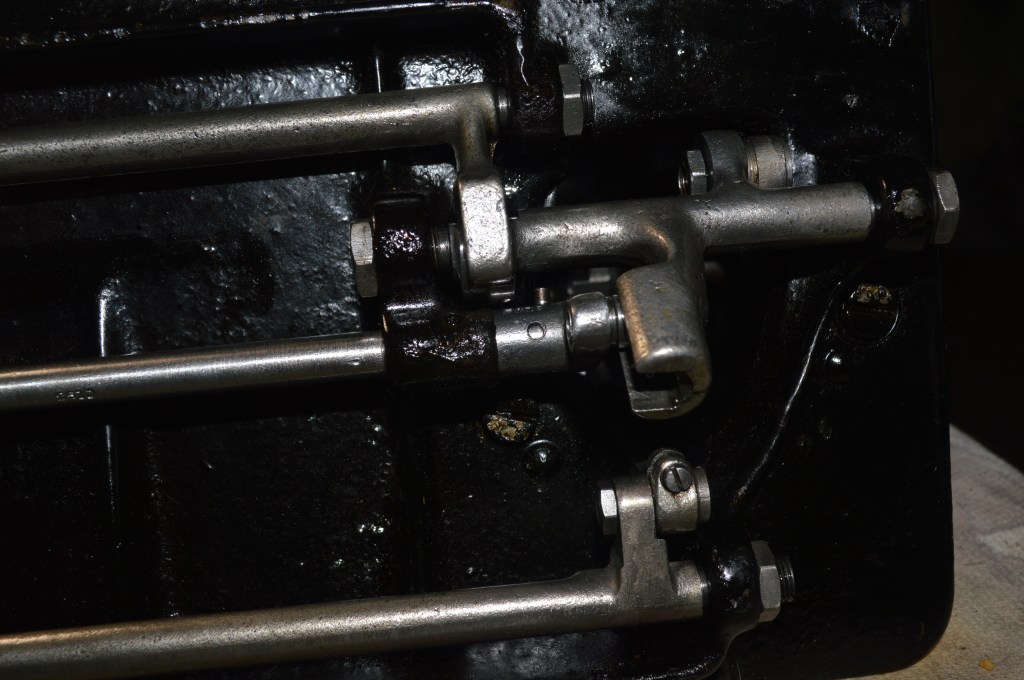

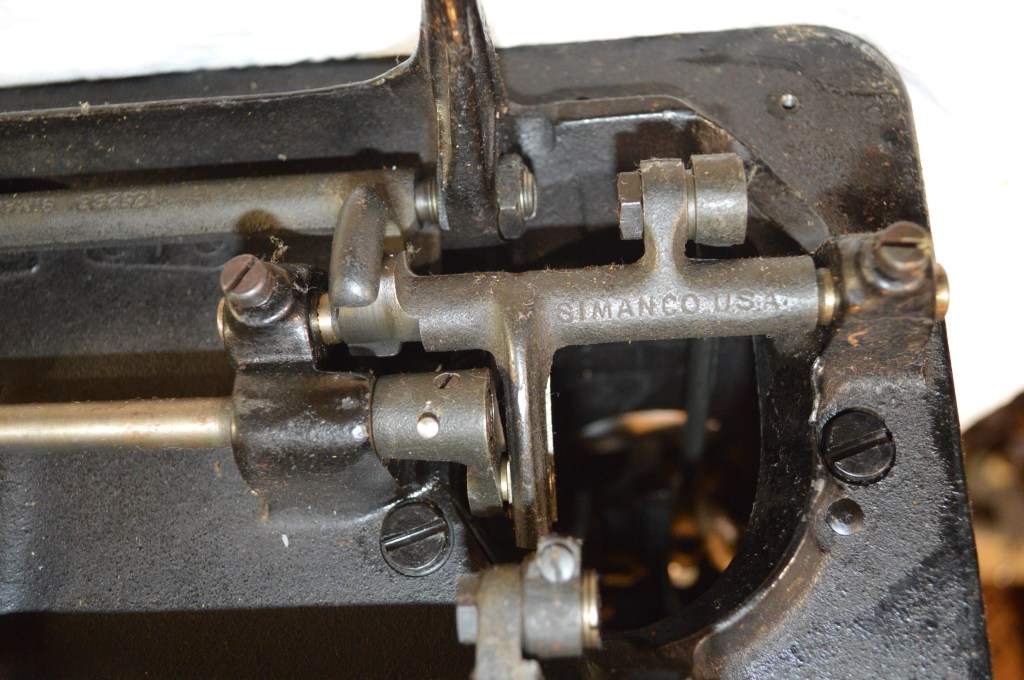

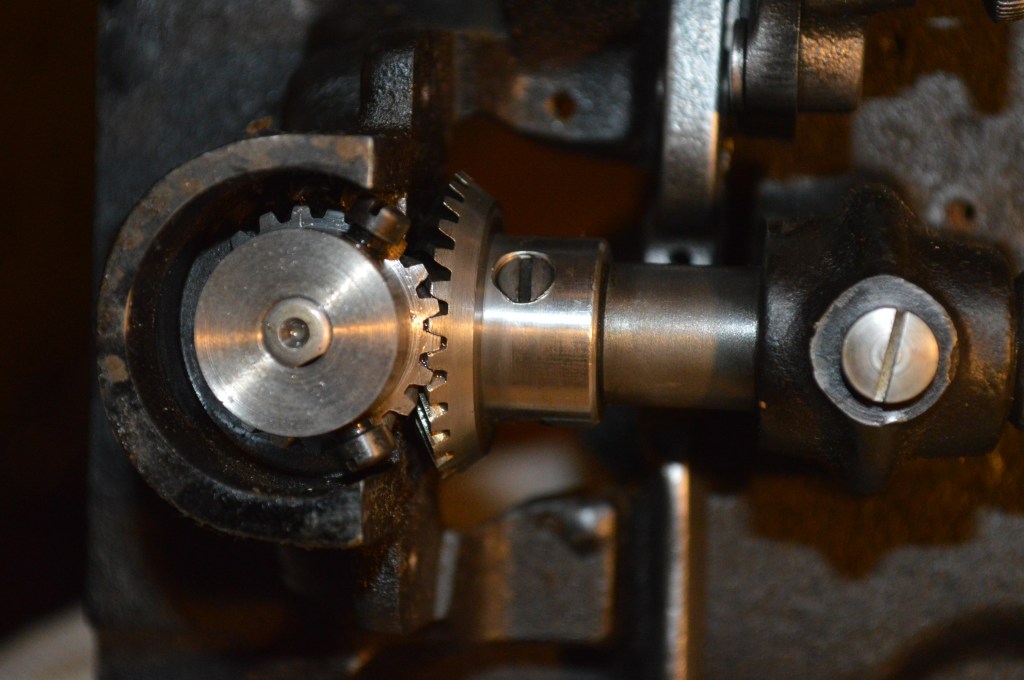

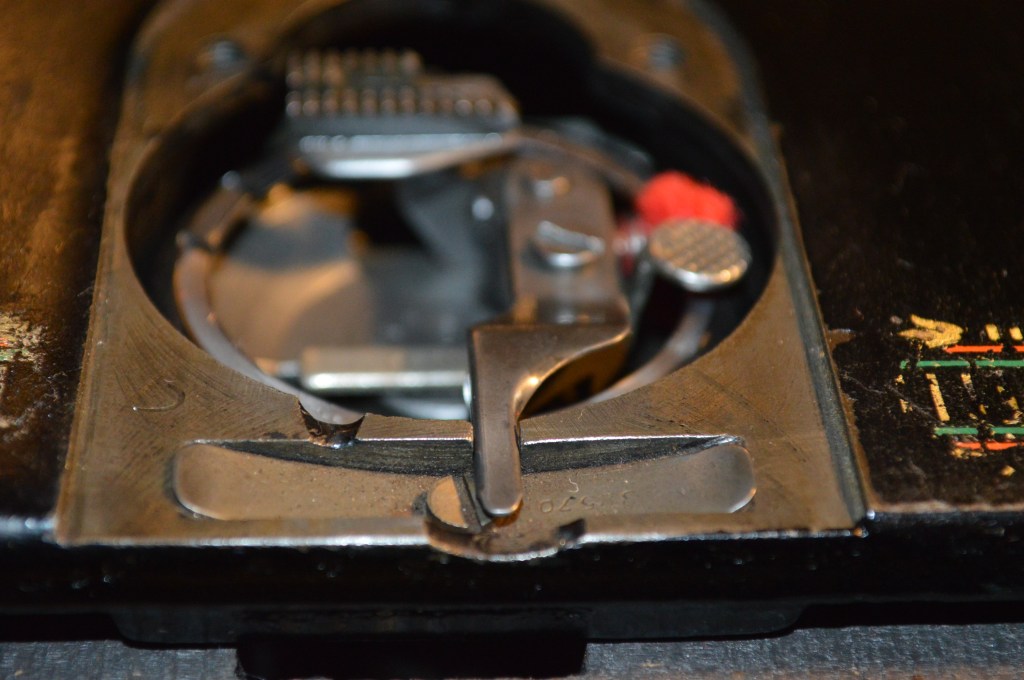

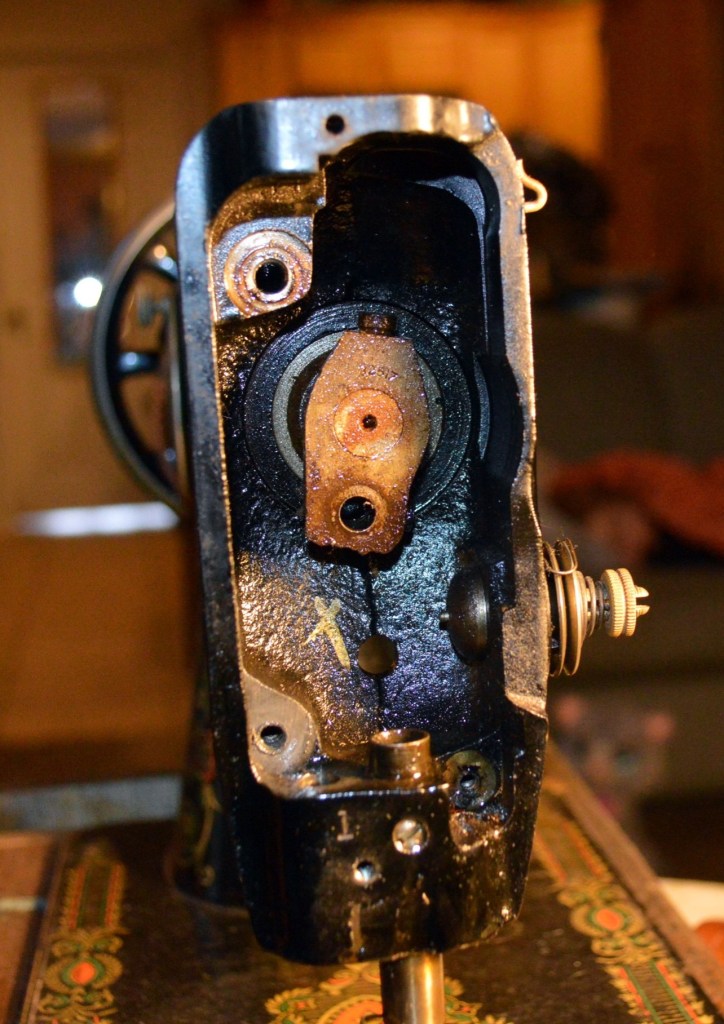

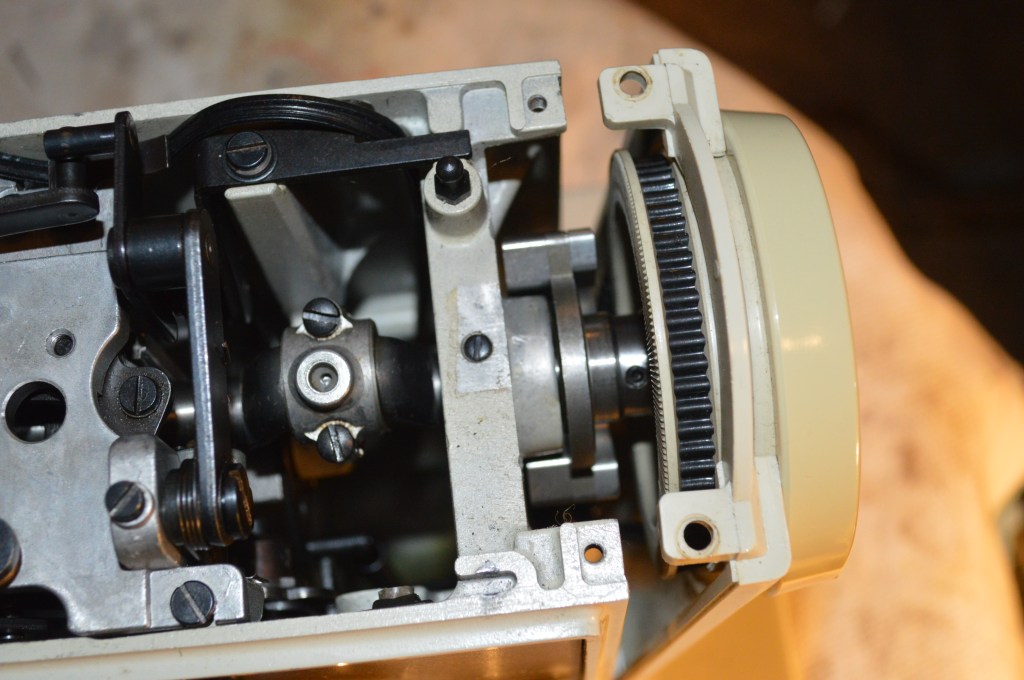

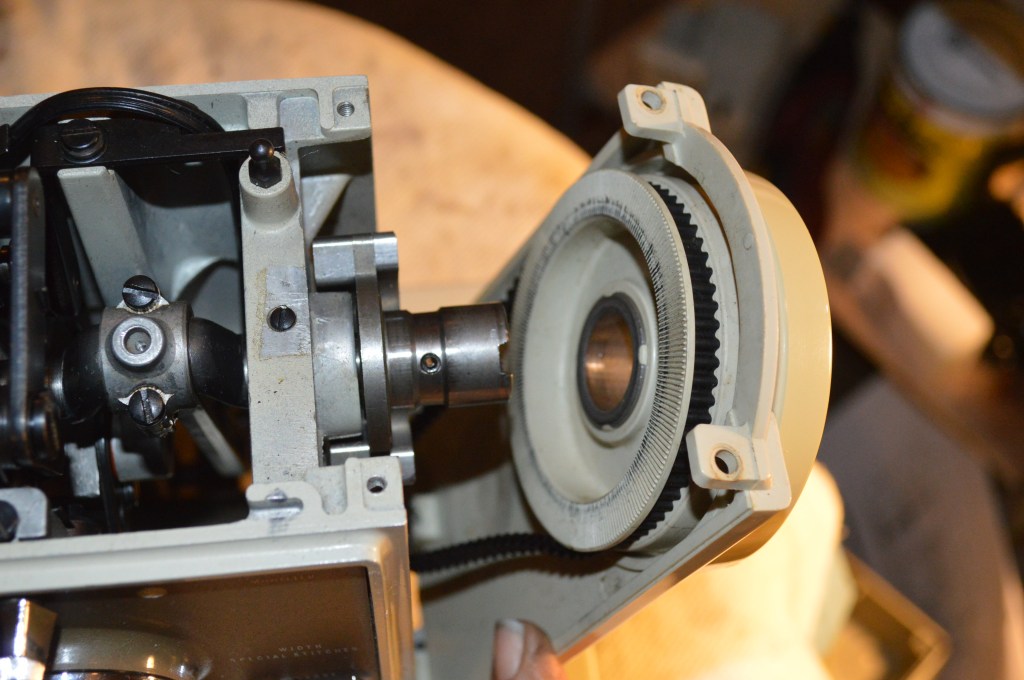

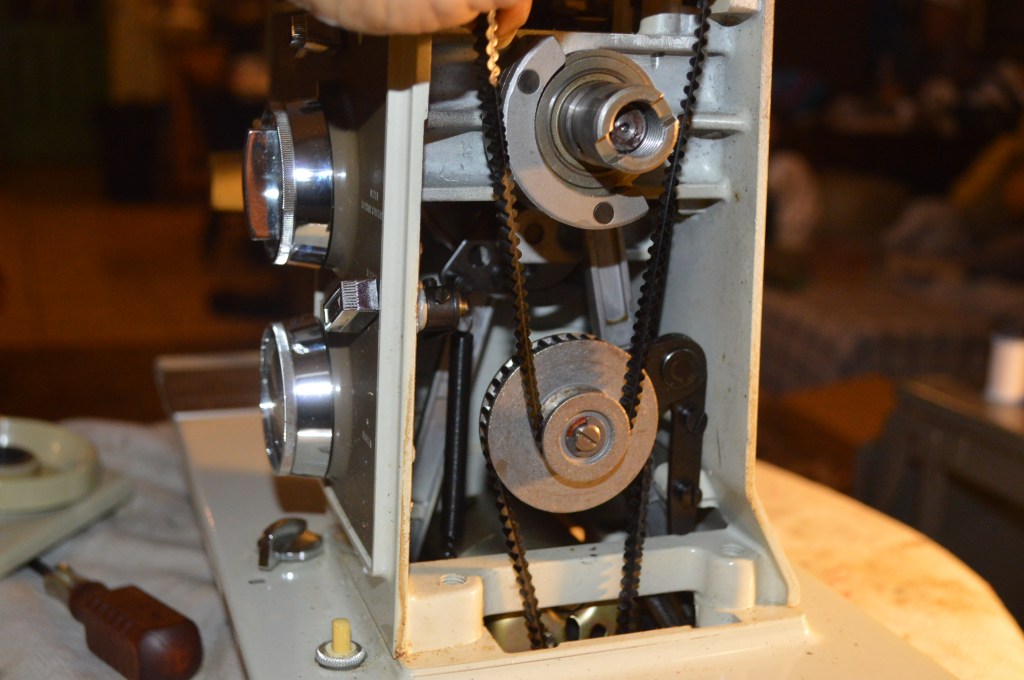

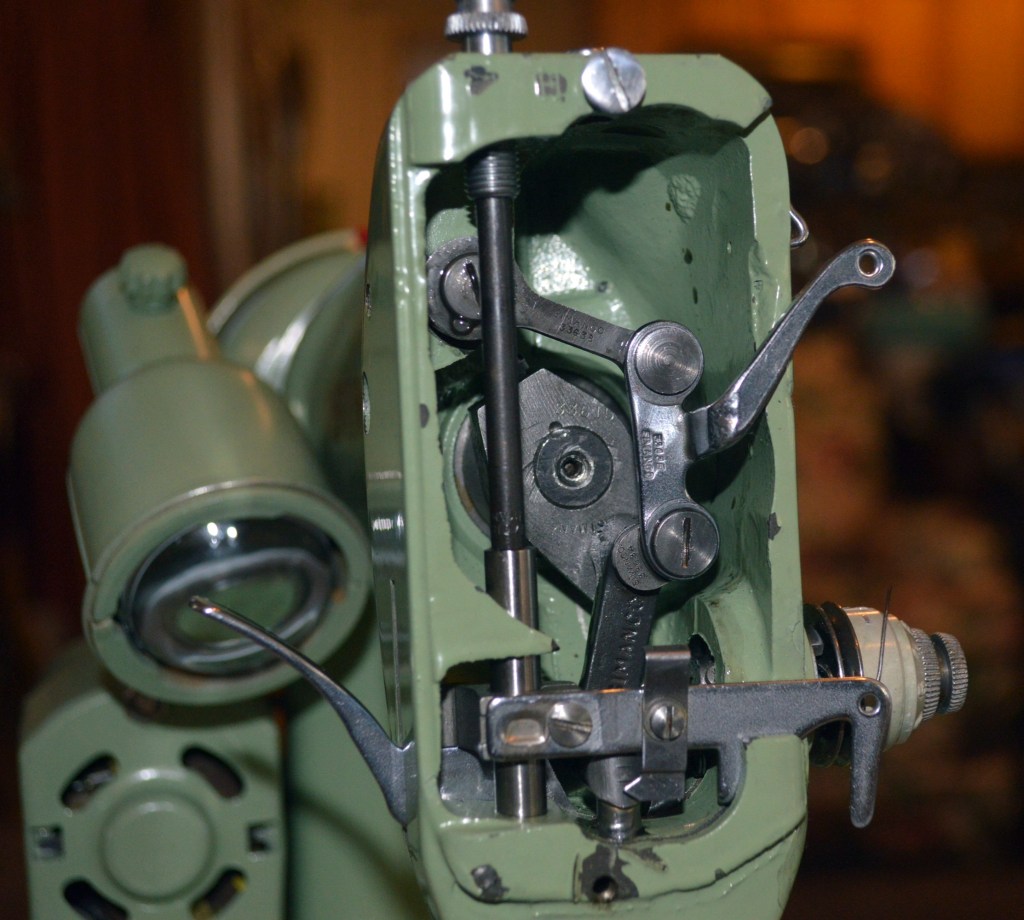

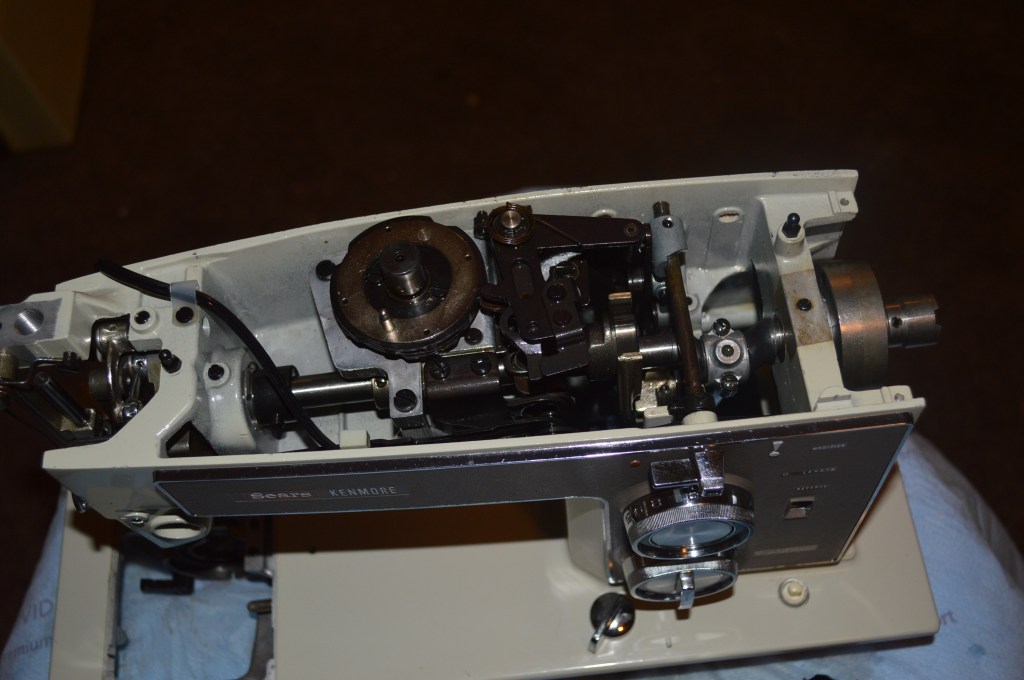

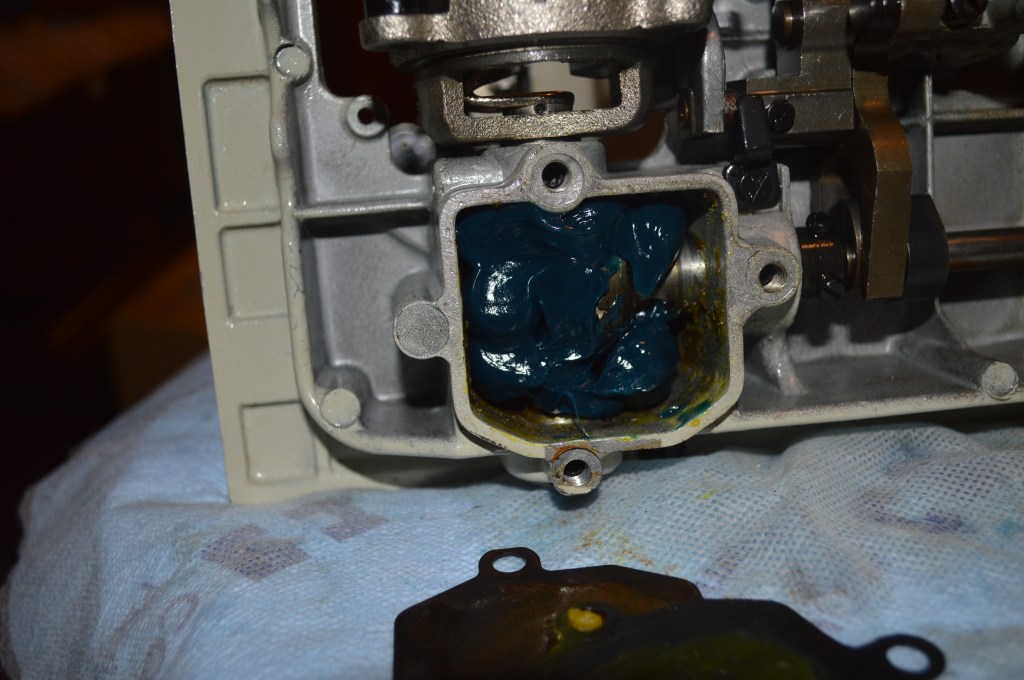

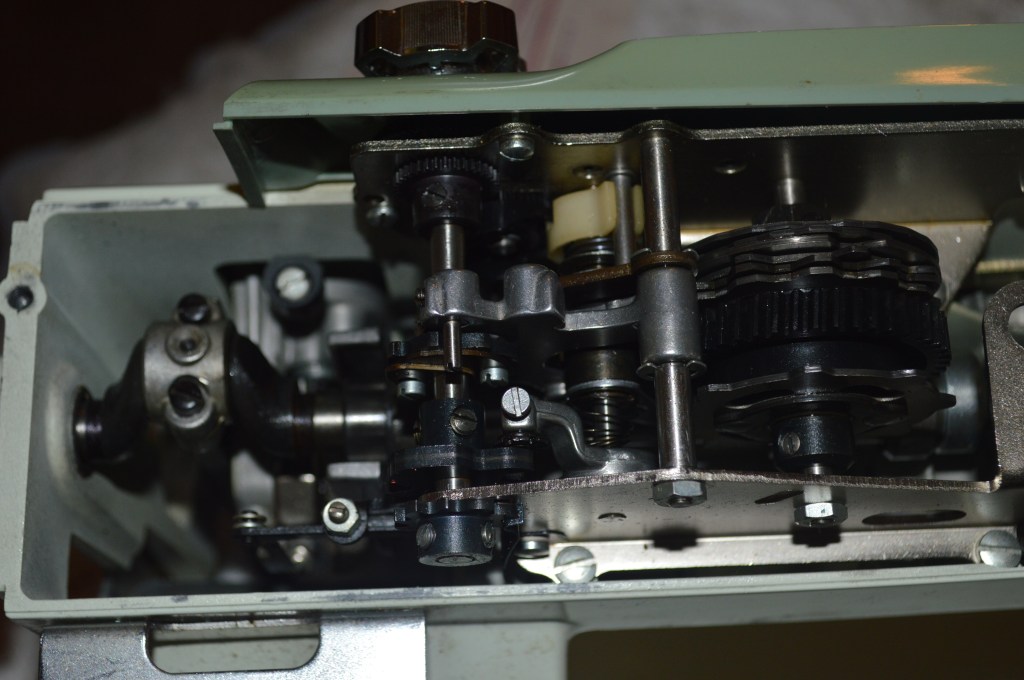

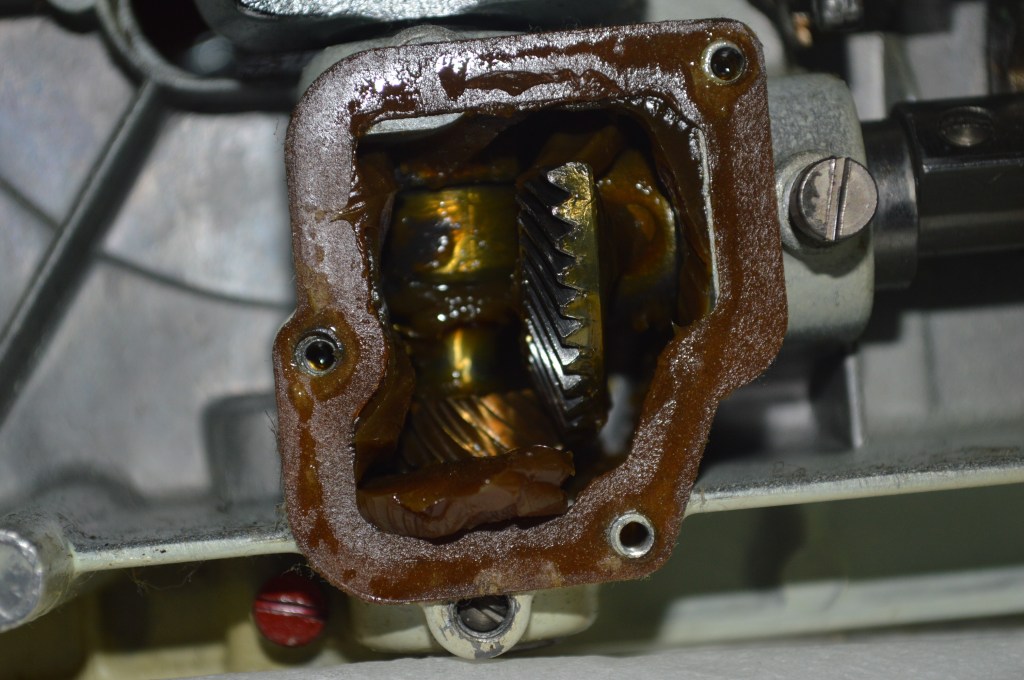

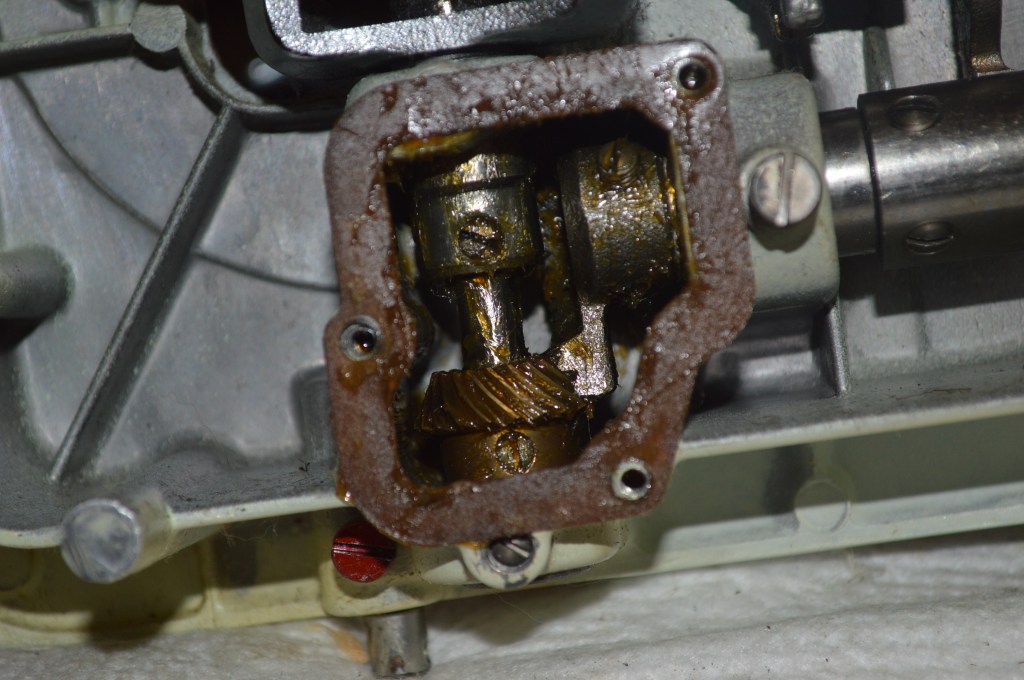

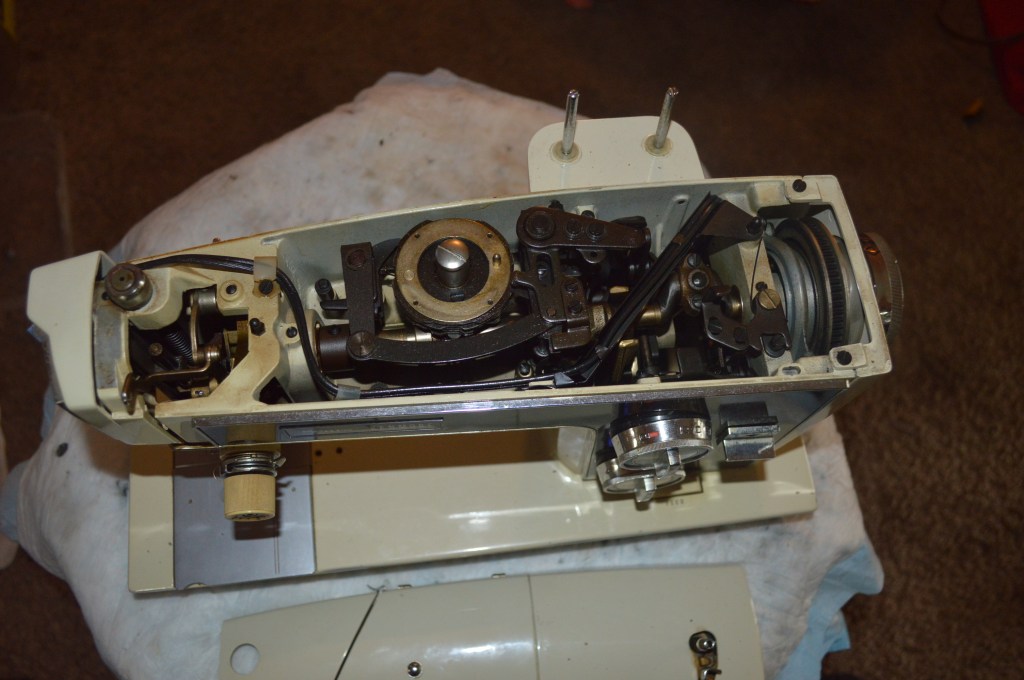

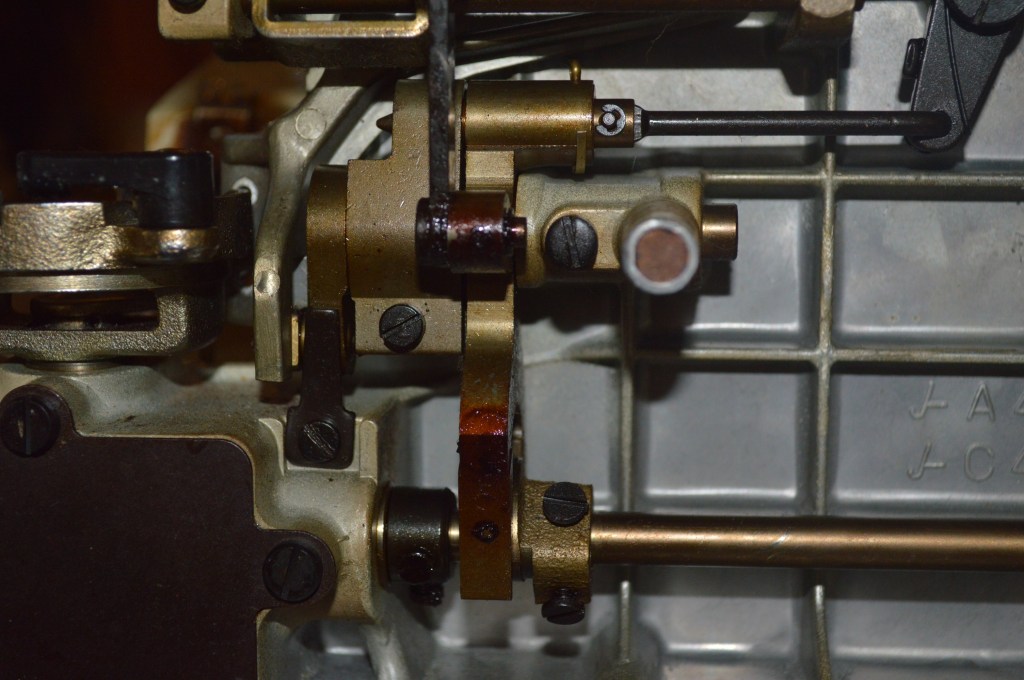

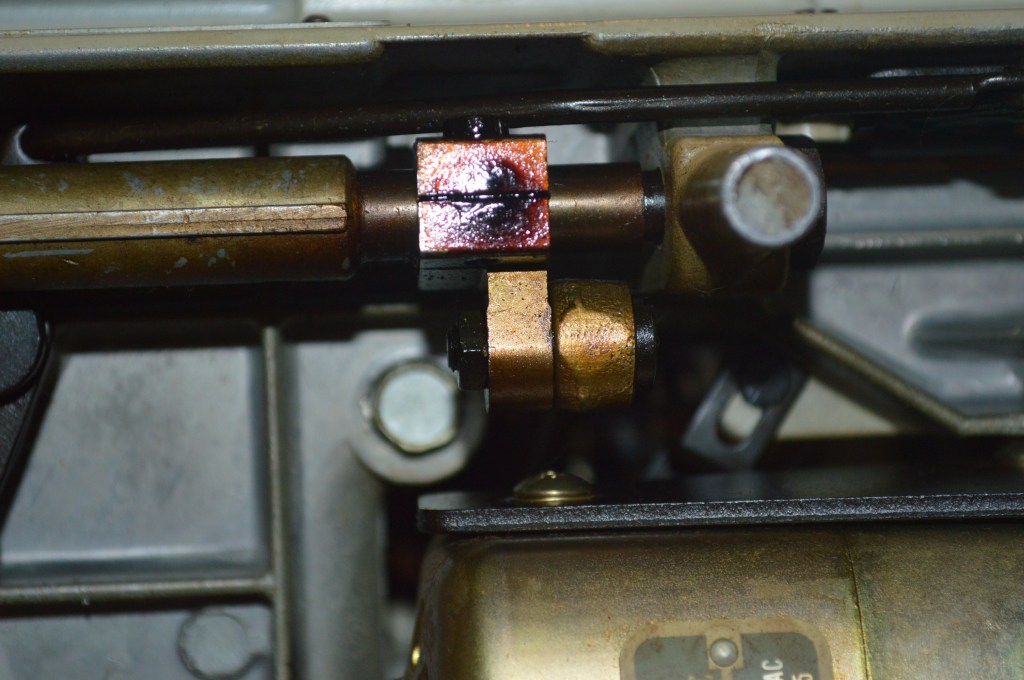

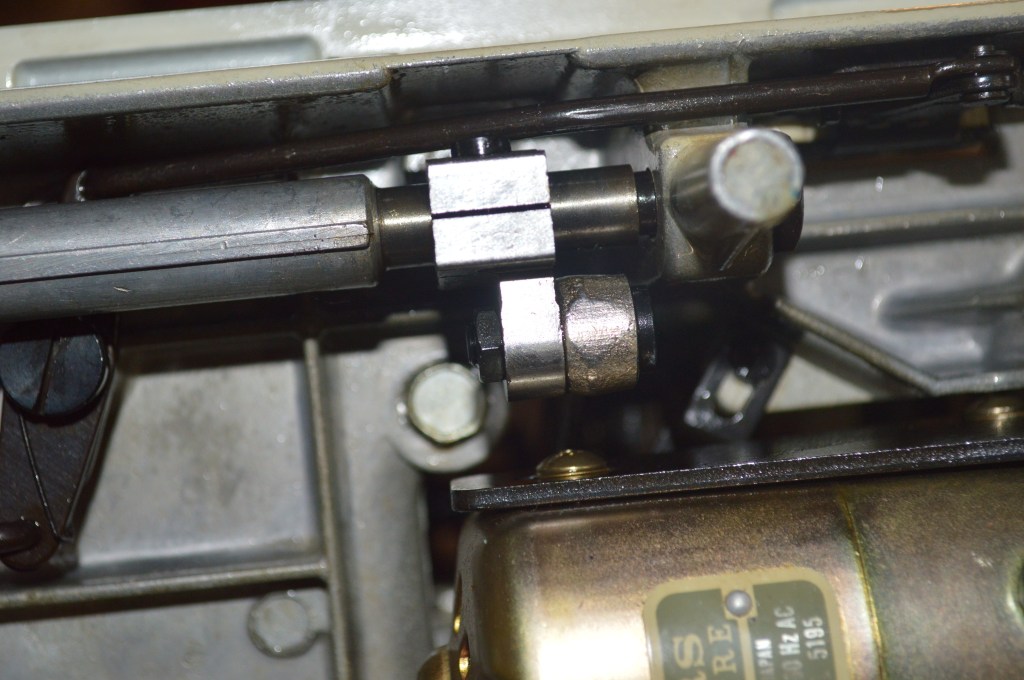

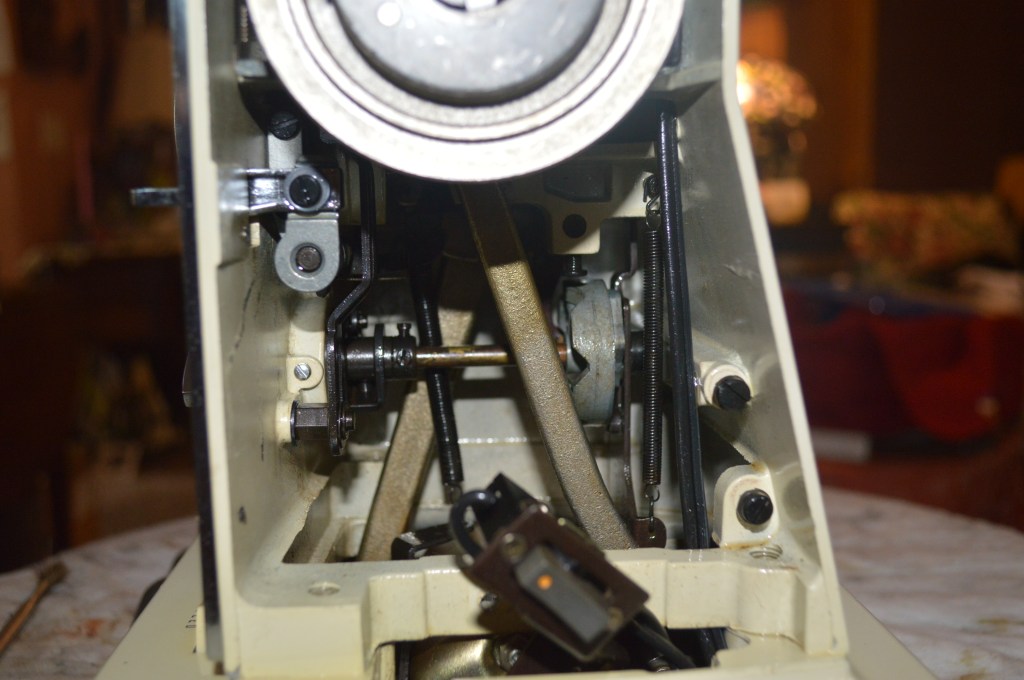

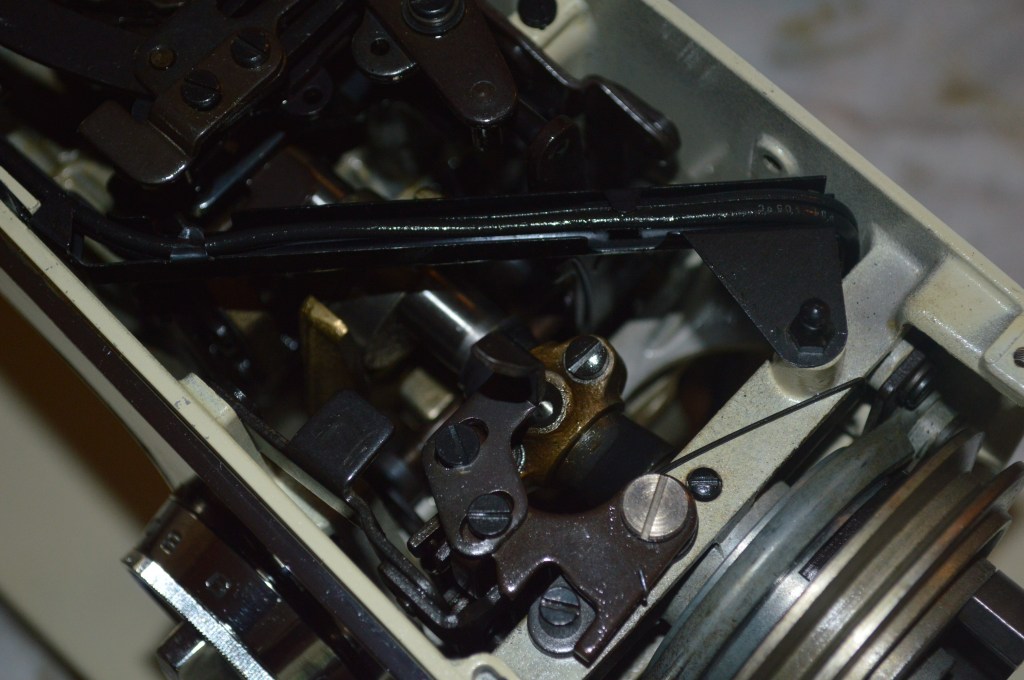

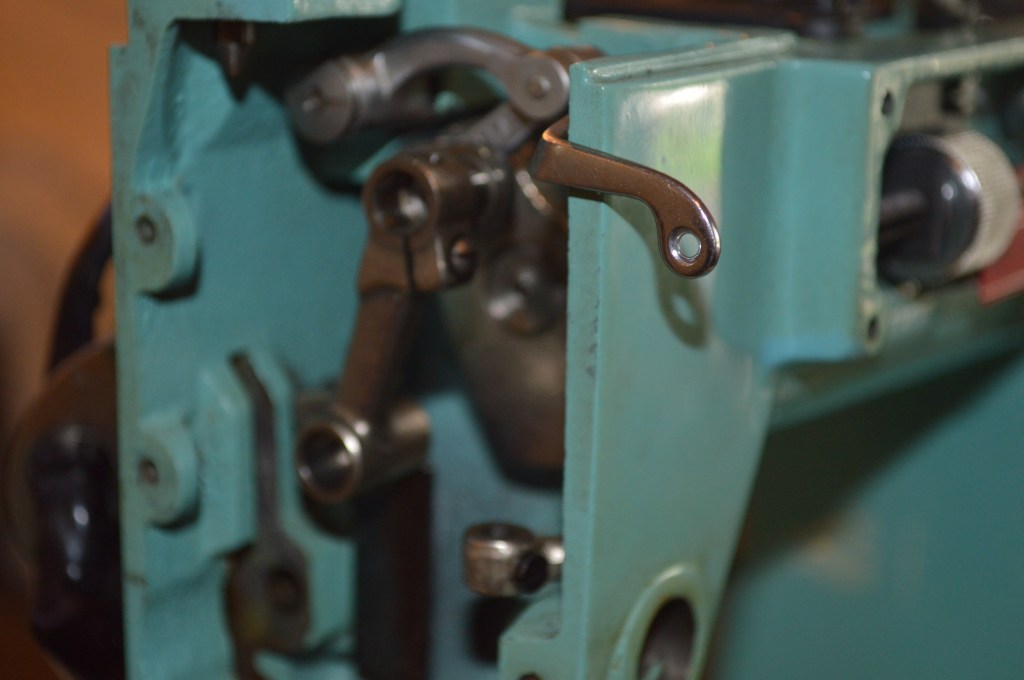

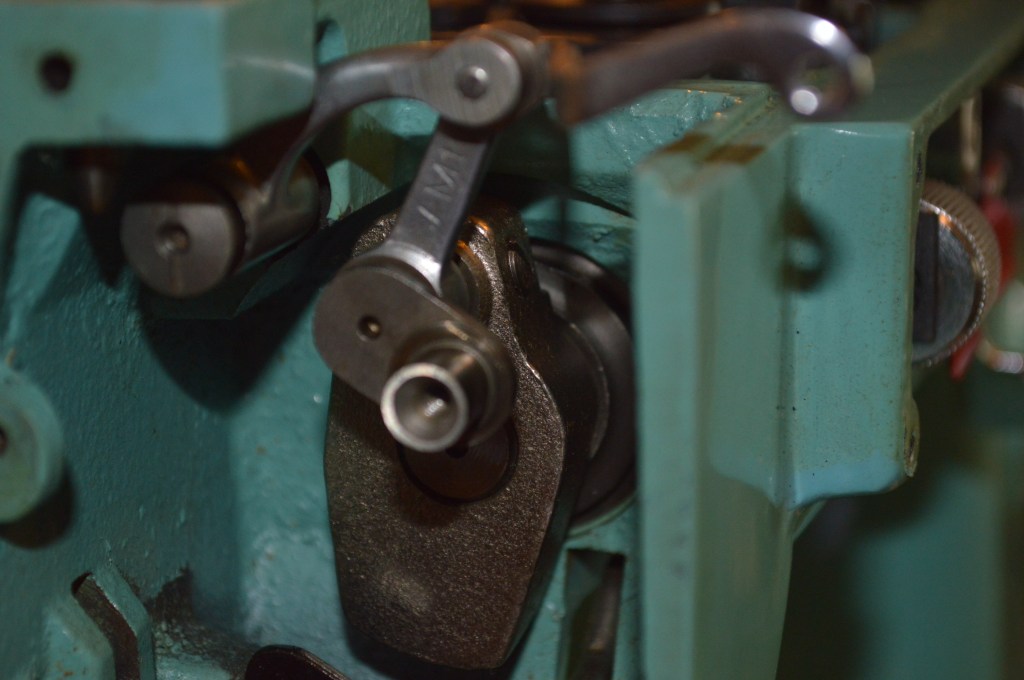

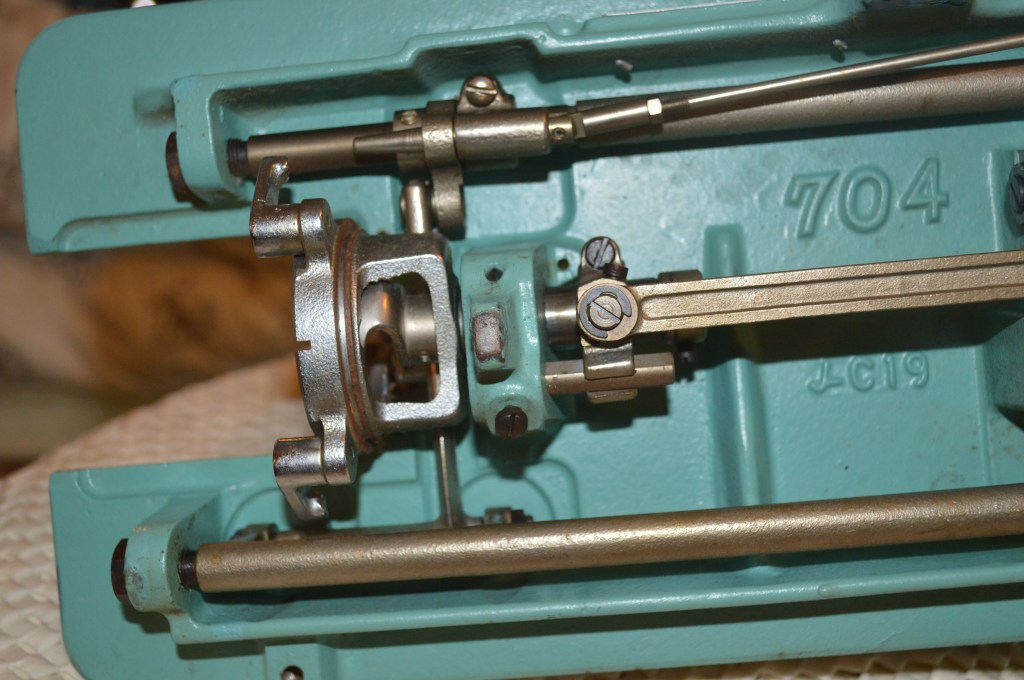

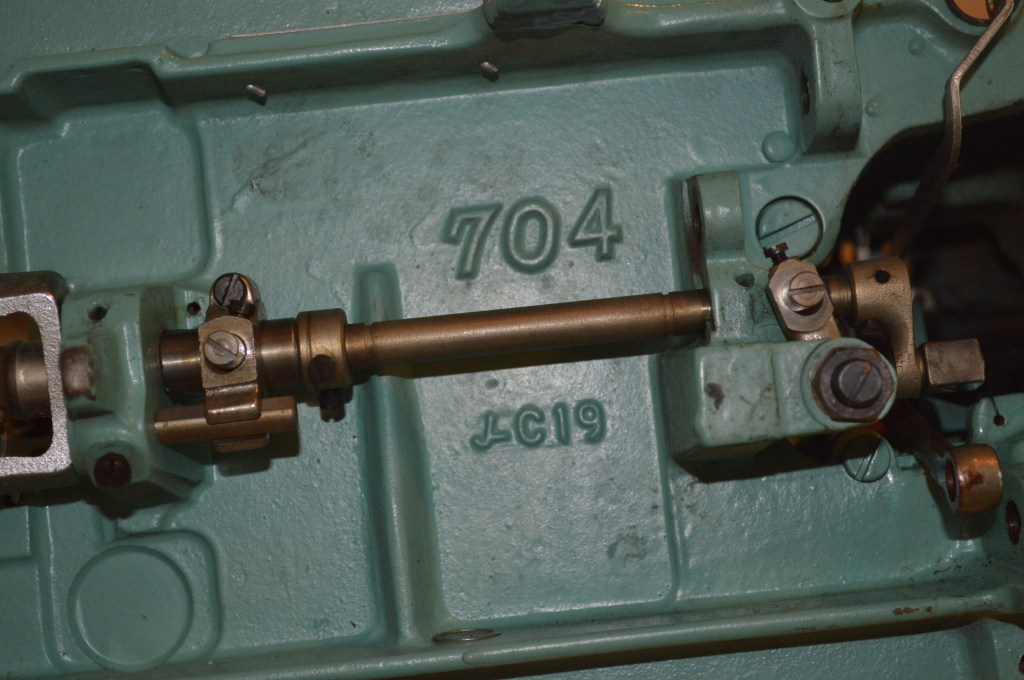

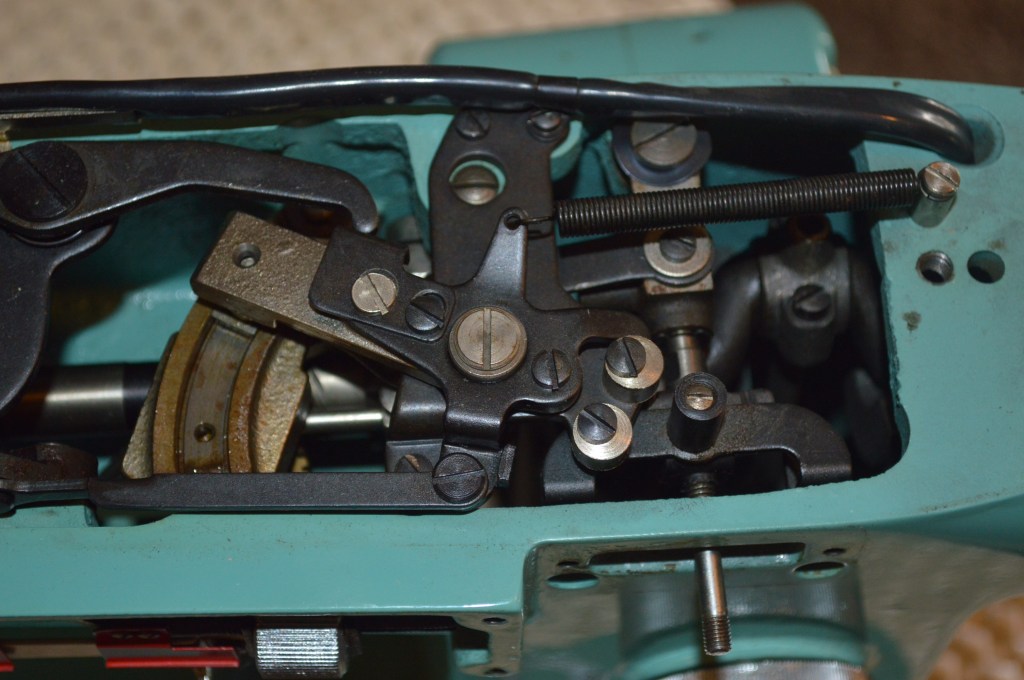

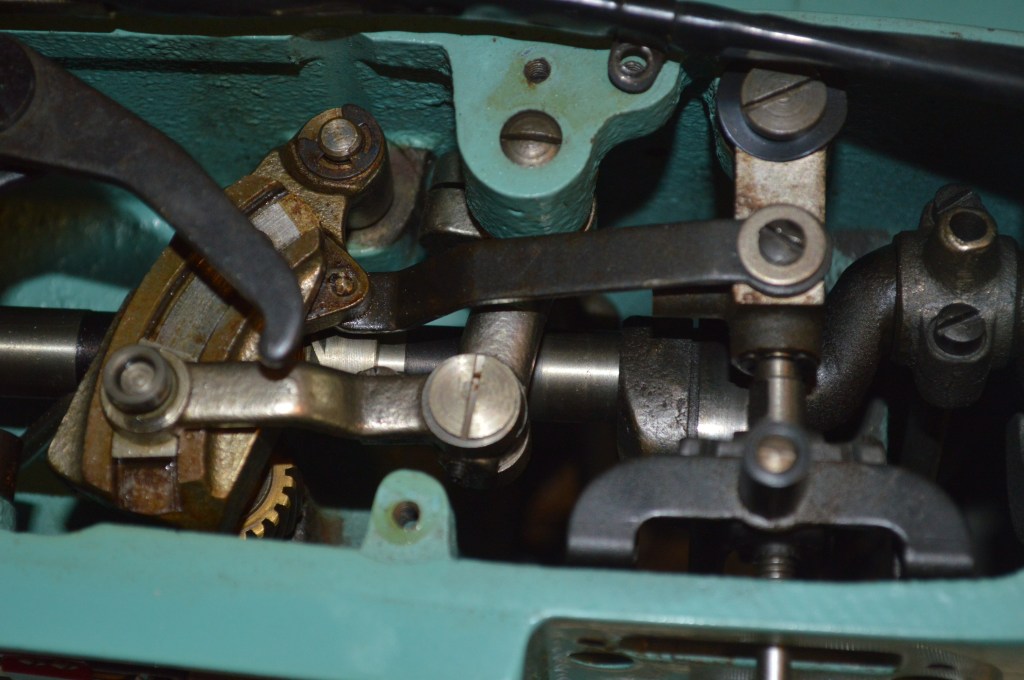

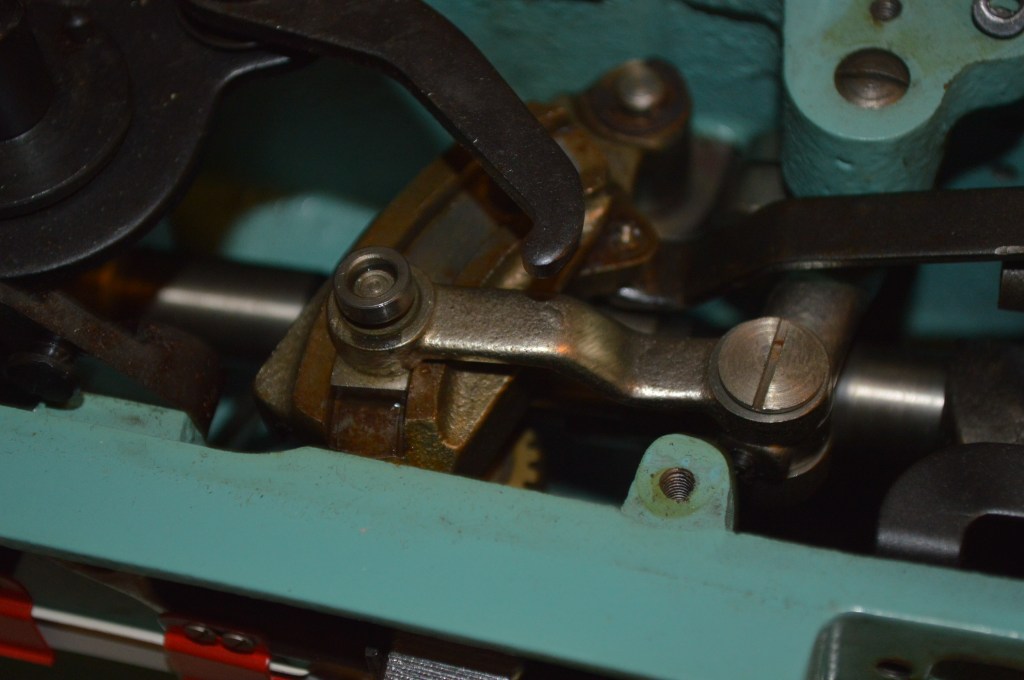

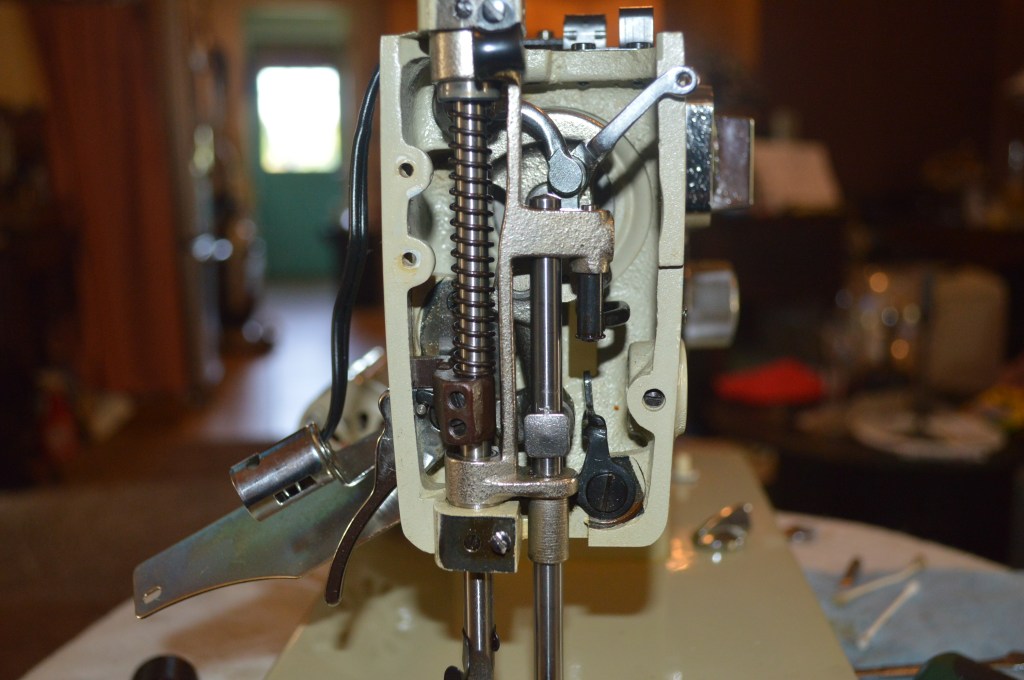

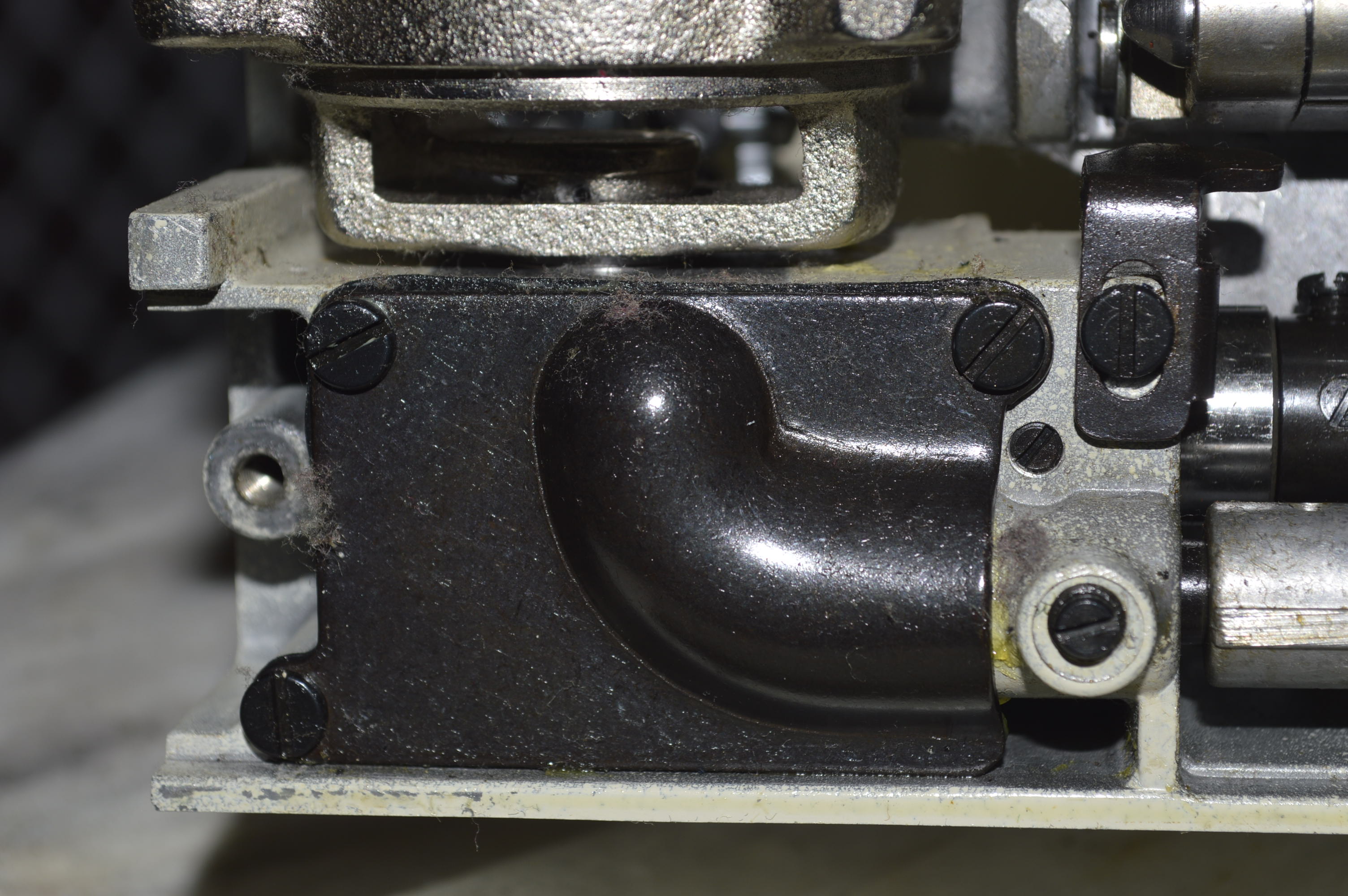

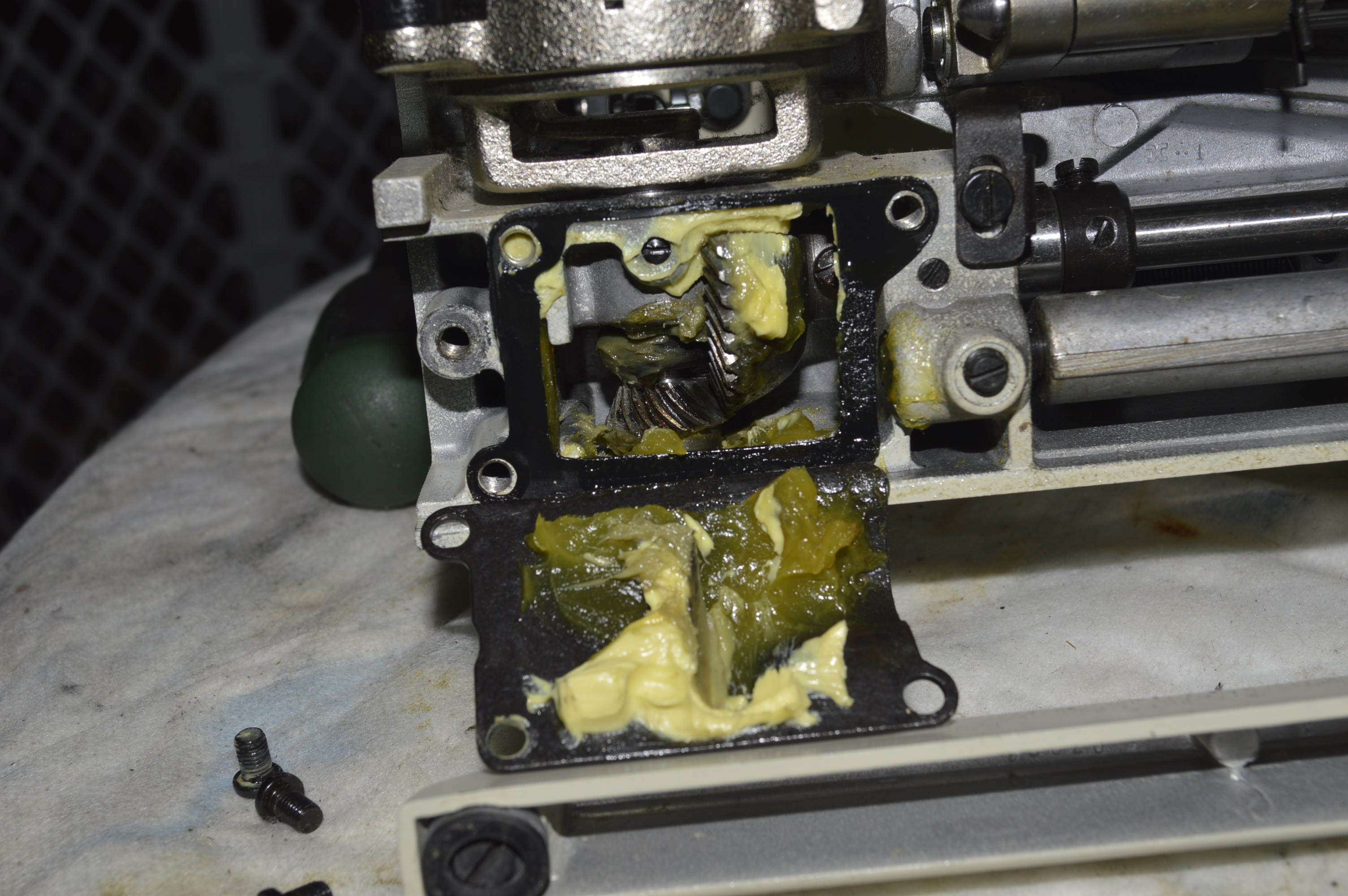

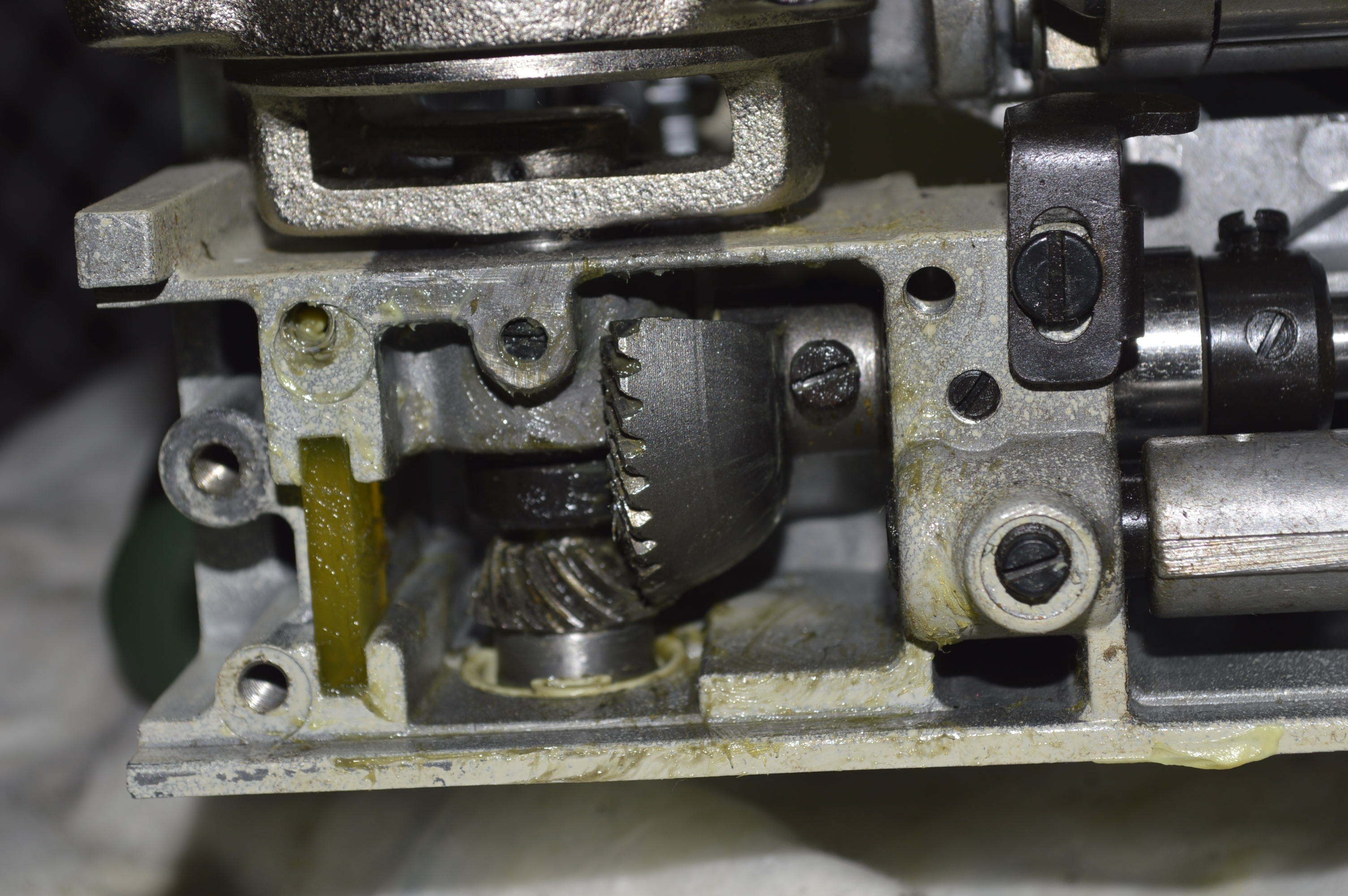

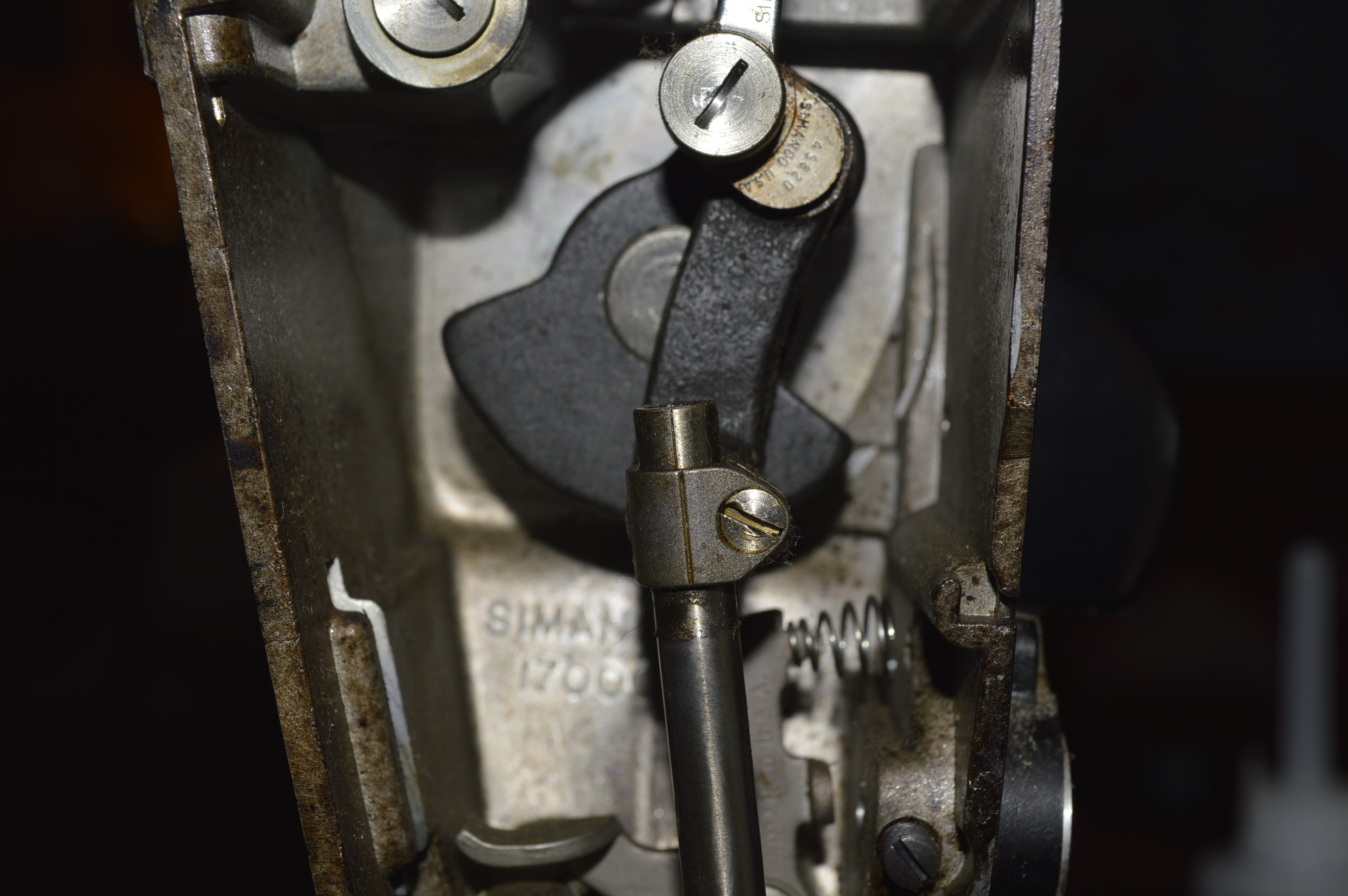

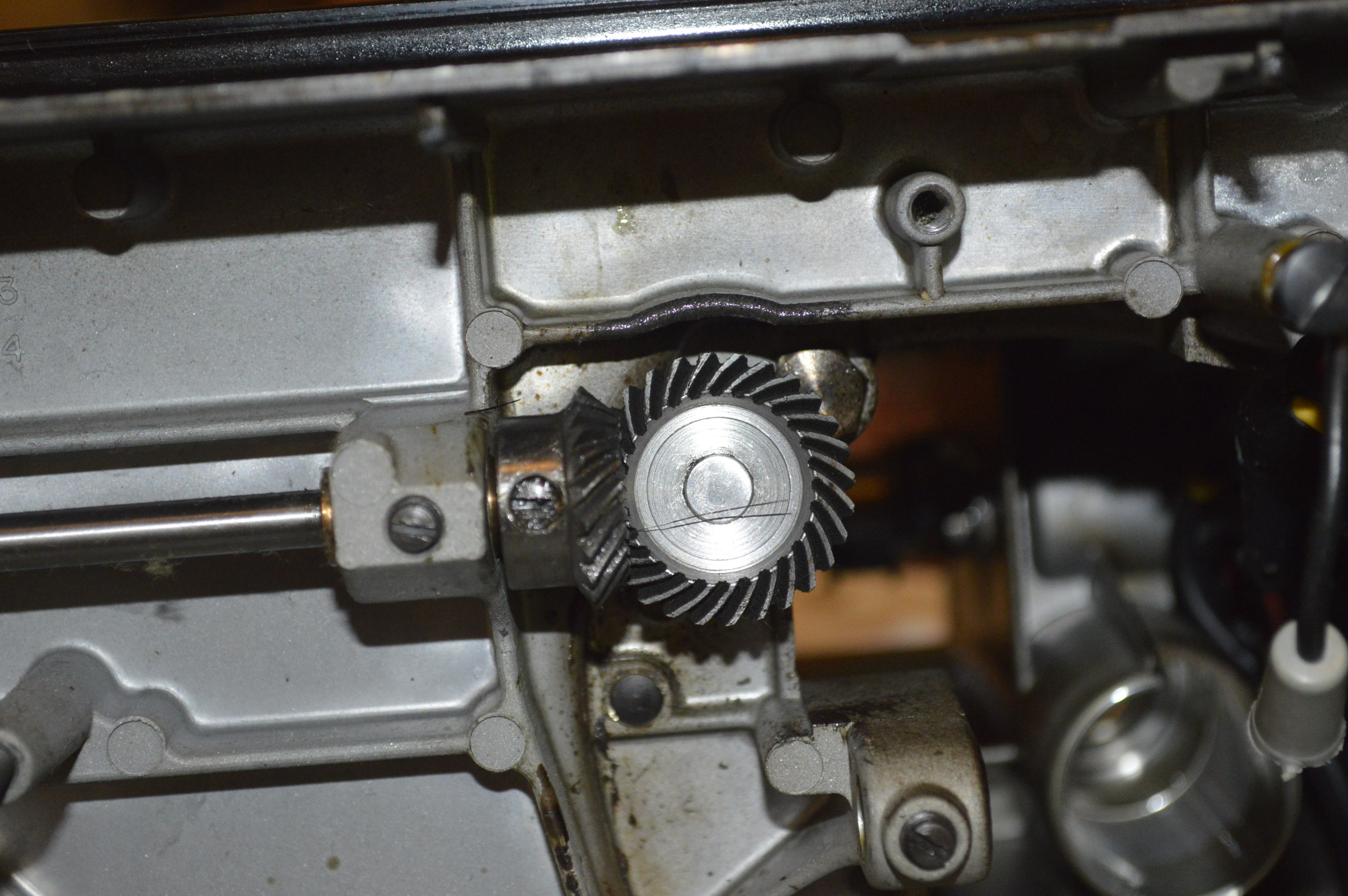

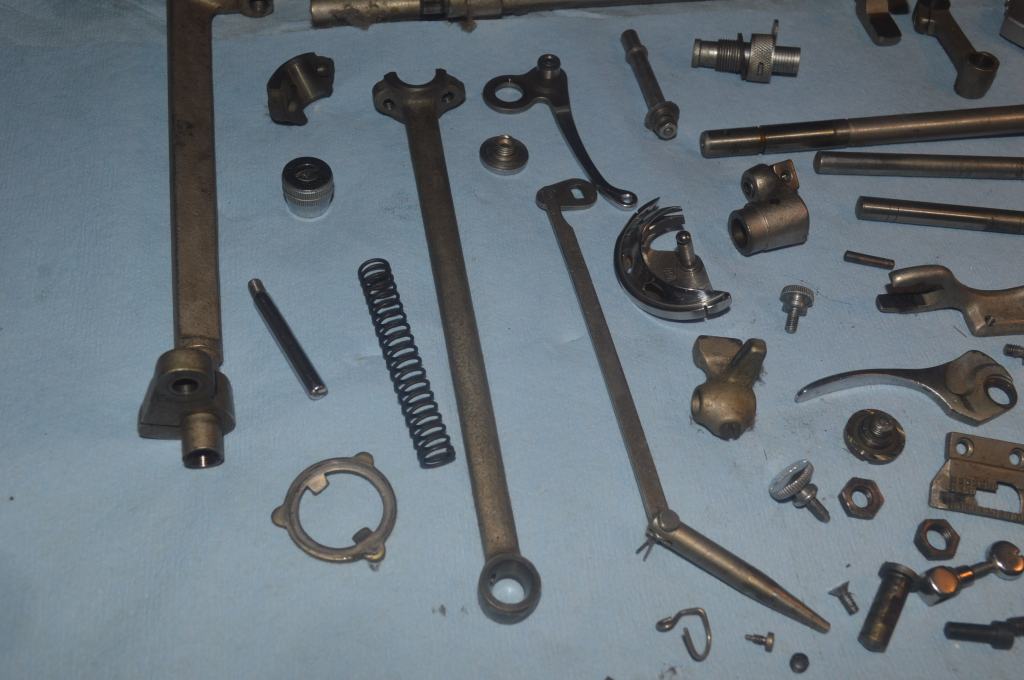

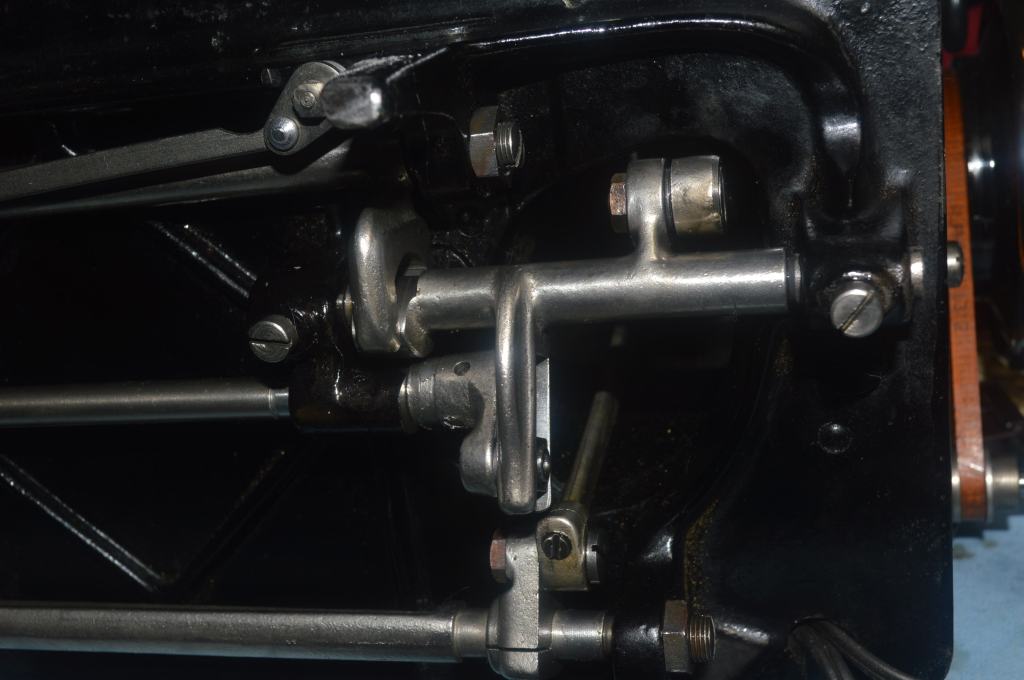

The plan included the disassembly of the top shaft and stitch length fork… The following picture convinced me not to attept this.

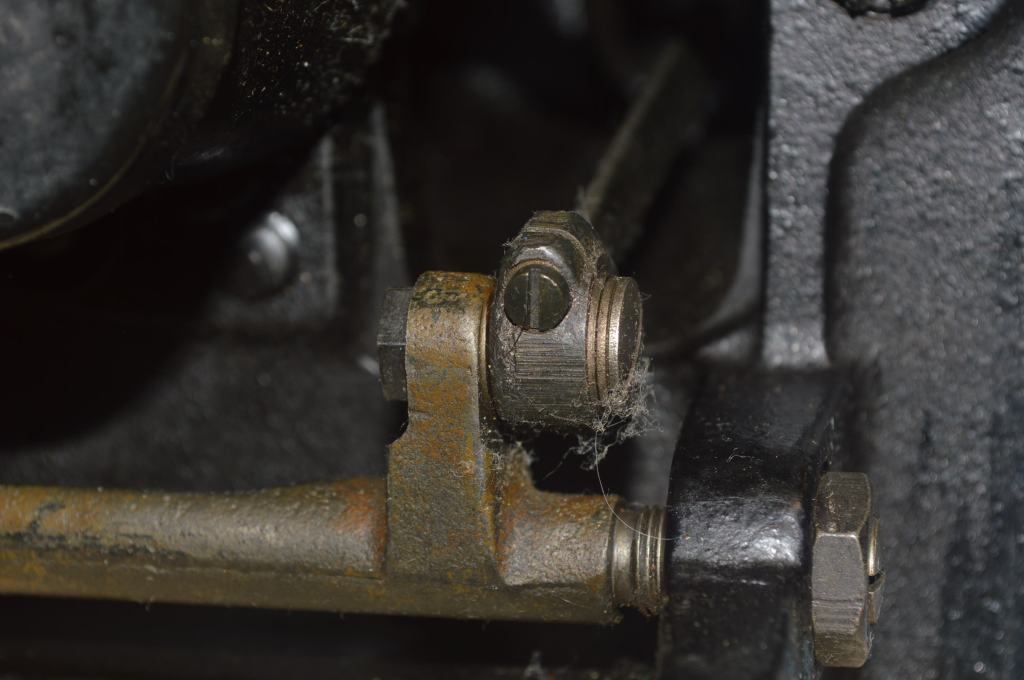

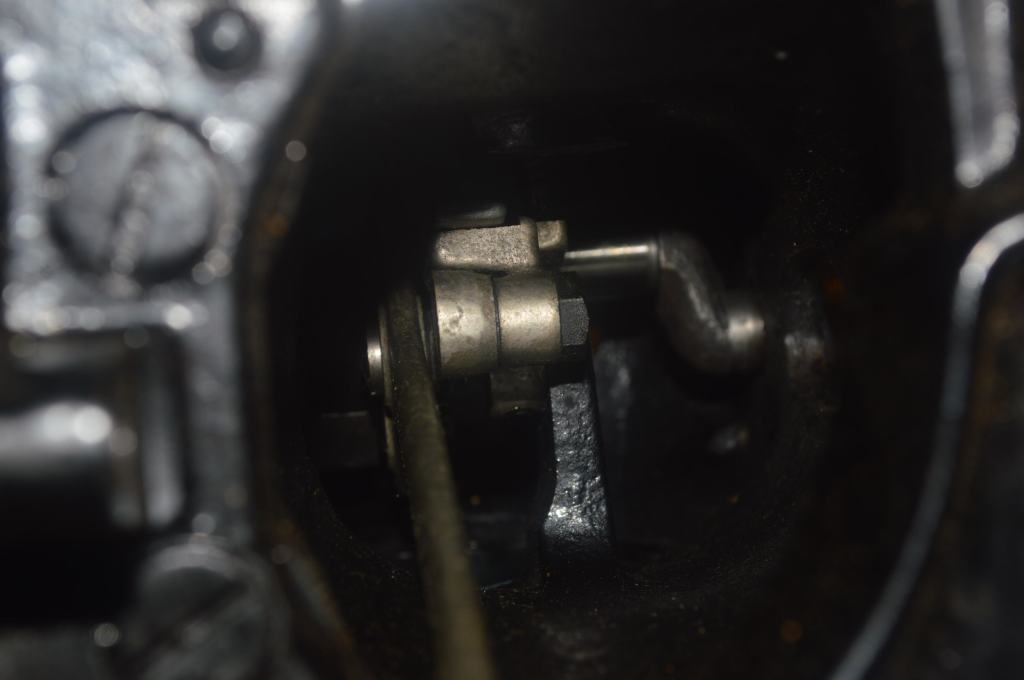

All of those likages fit together and are attached to a single bolt on the machine deep in the pillar cavity. I thought about it long and hard and decide that if I removed these assemblies I may never get them back together and in place. Rather than risk this, I decided to clean them in place. Luckily, the arm shaft turns smoothly and I can work around its removal.

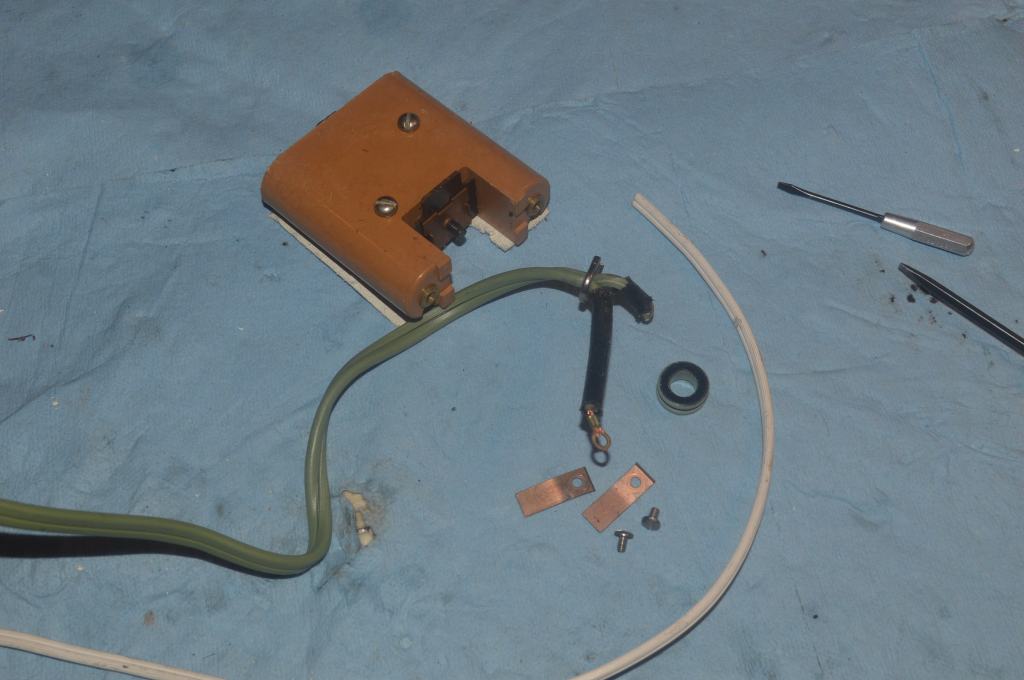

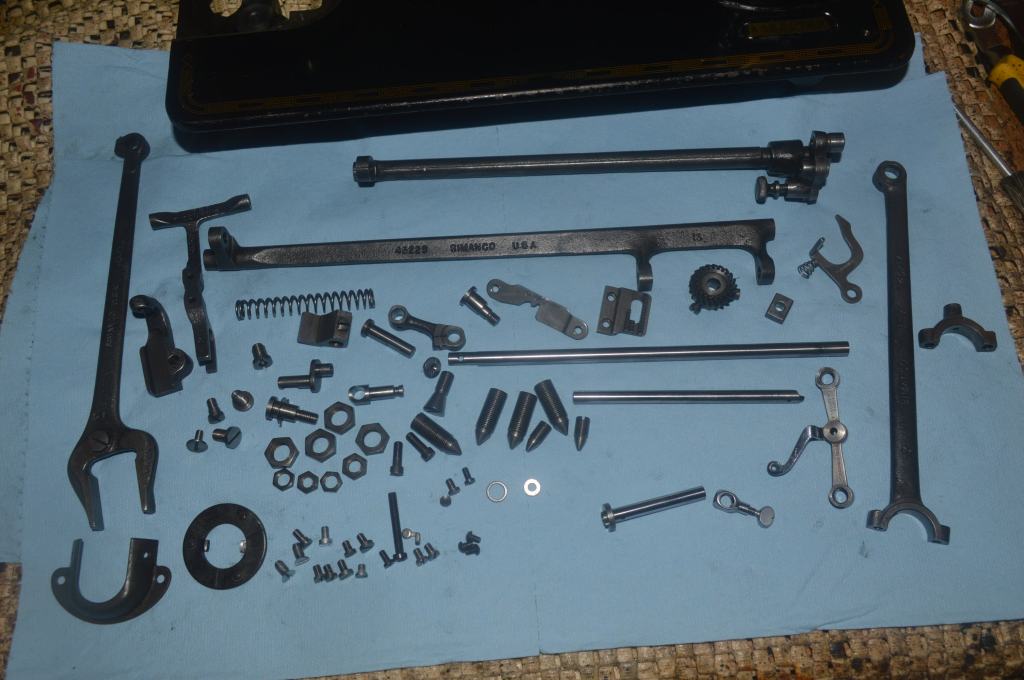

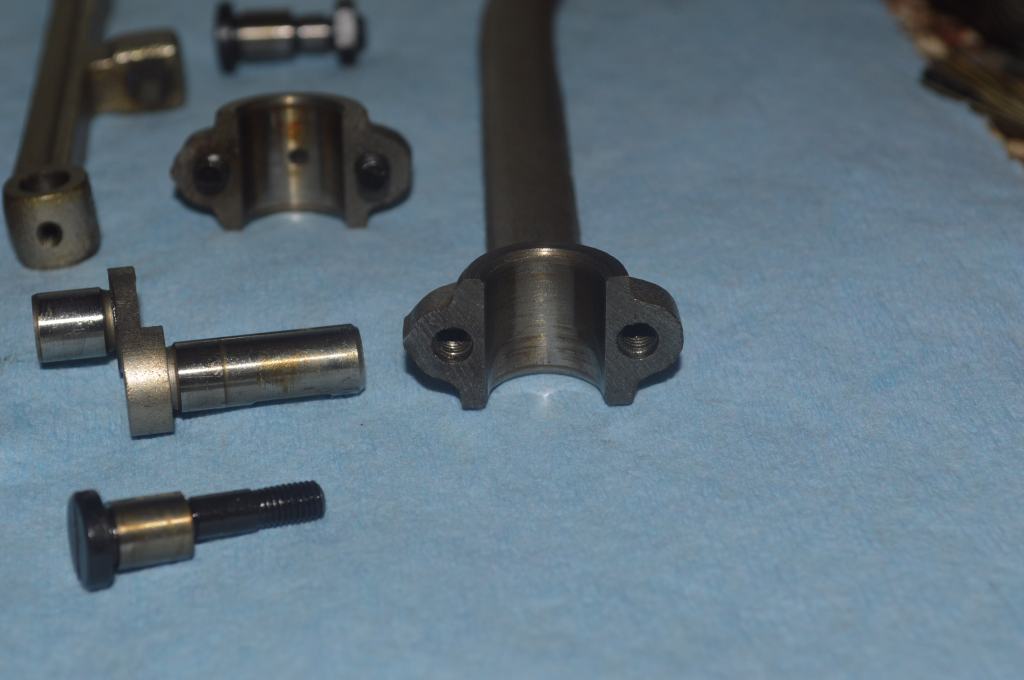

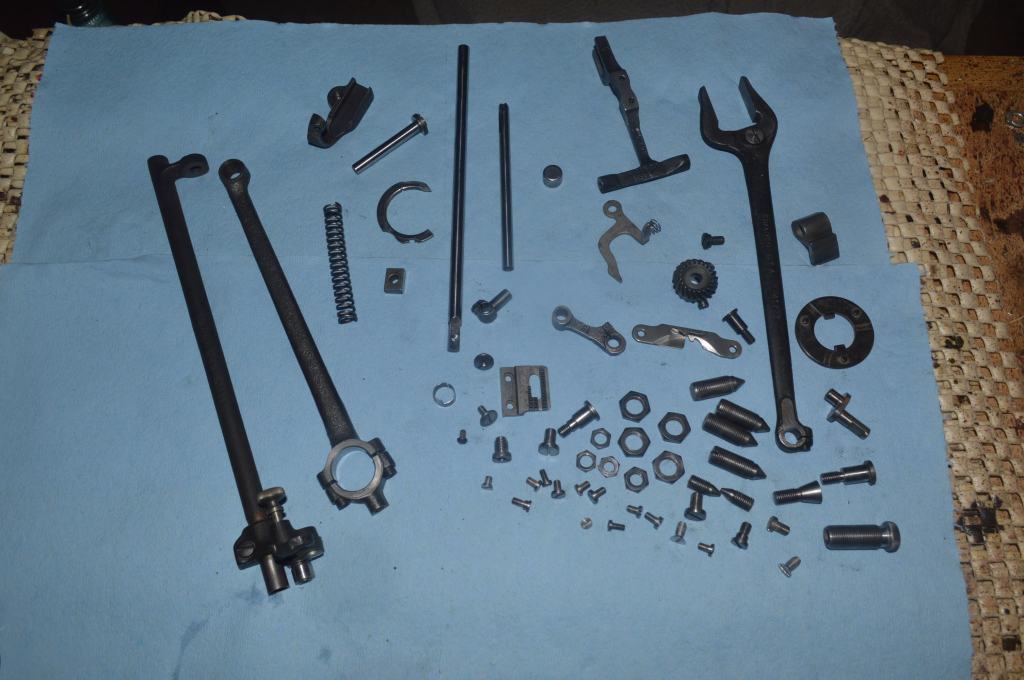

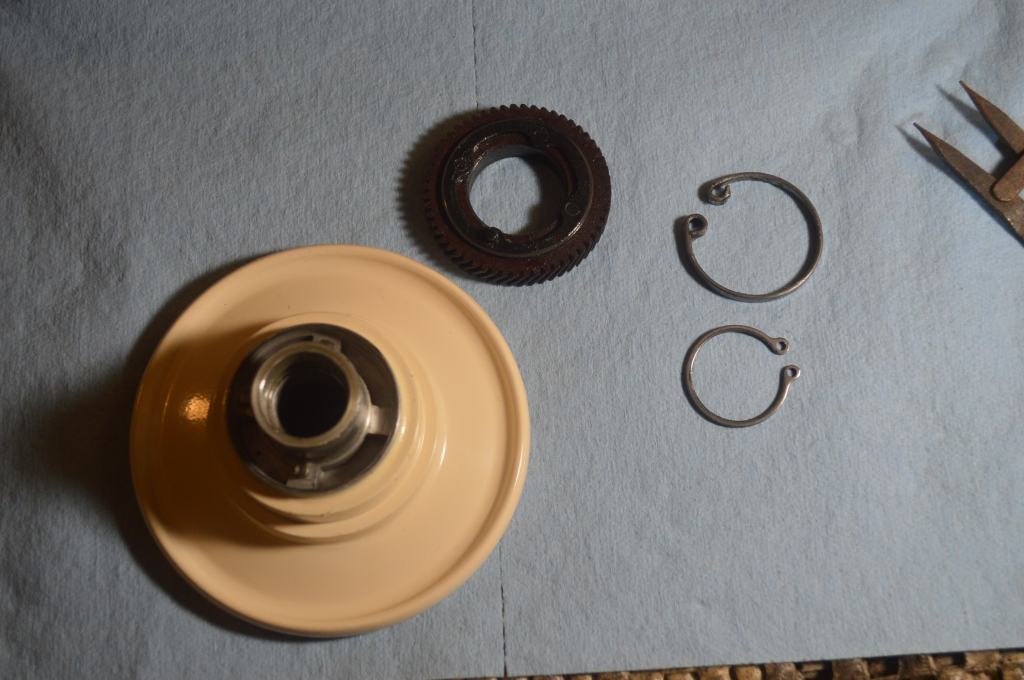

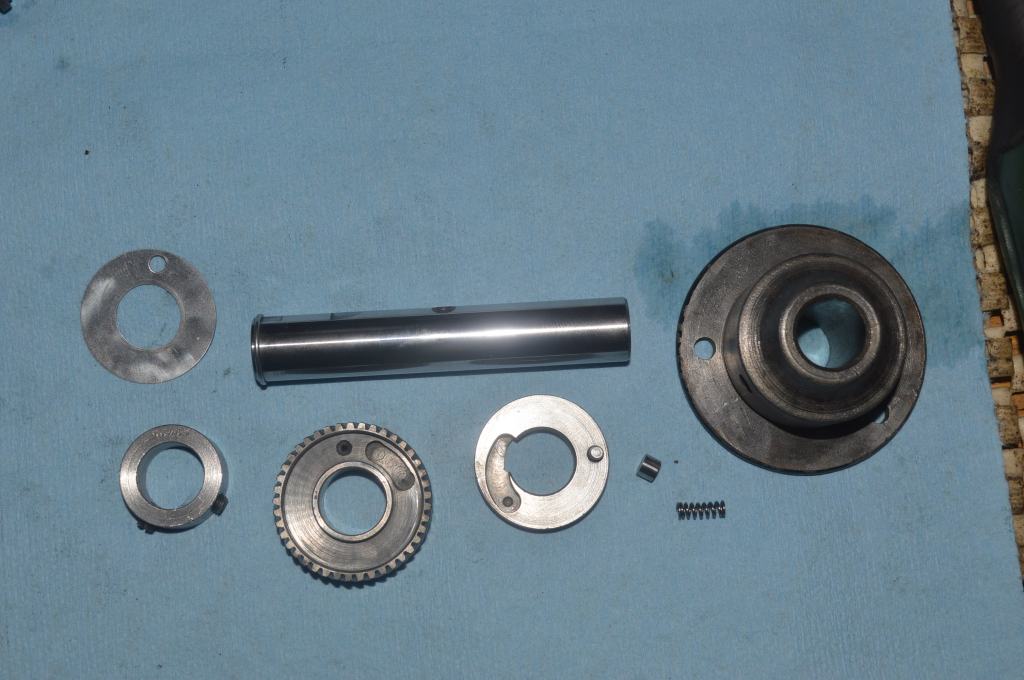

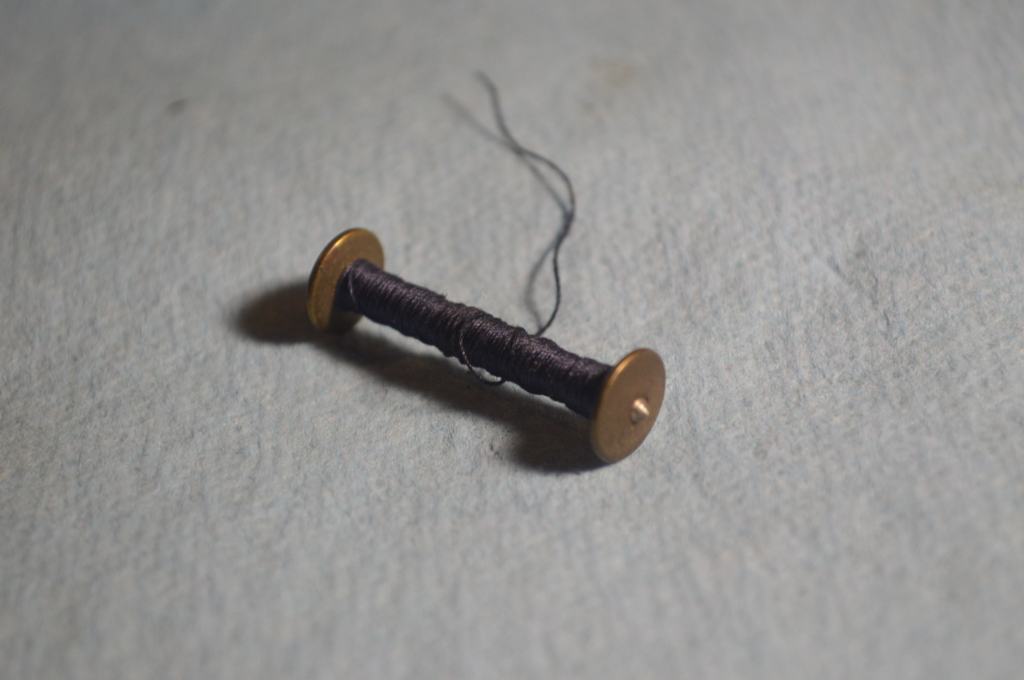

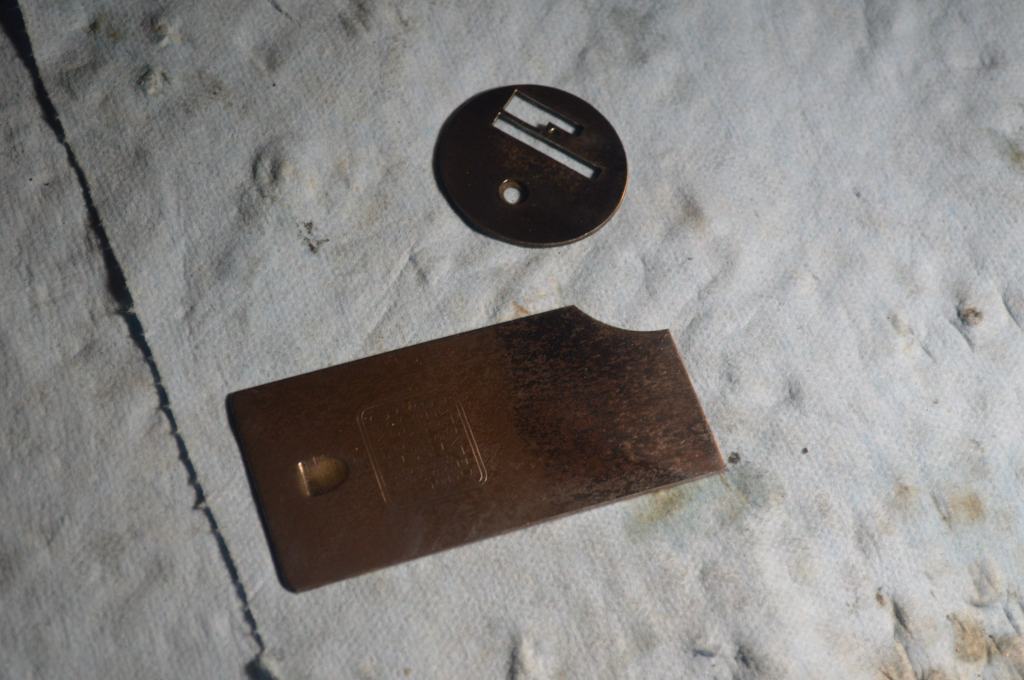

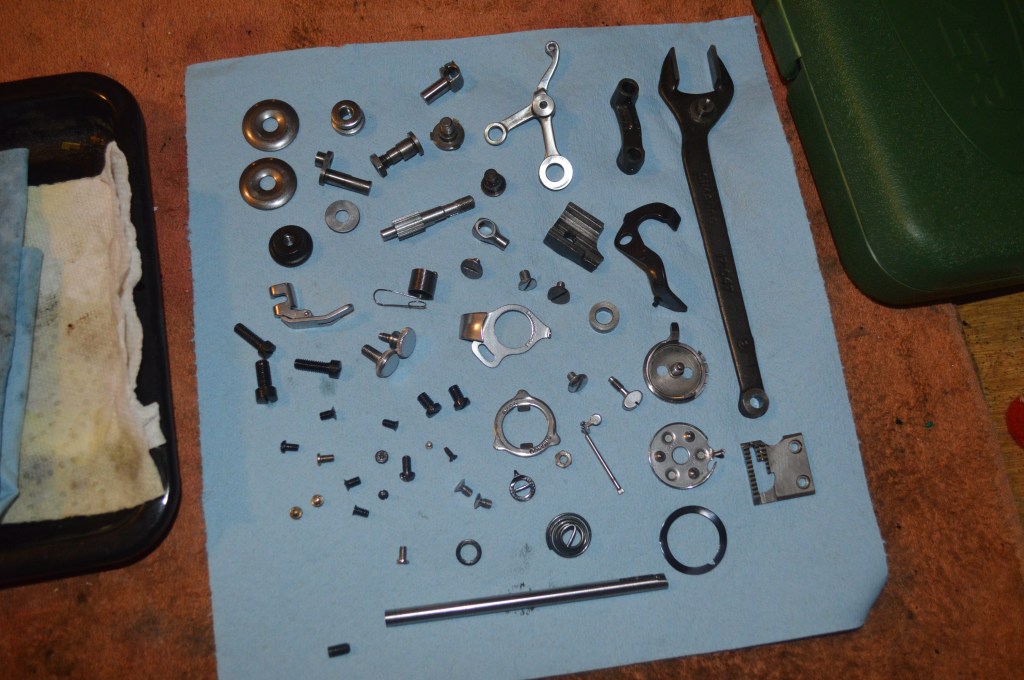

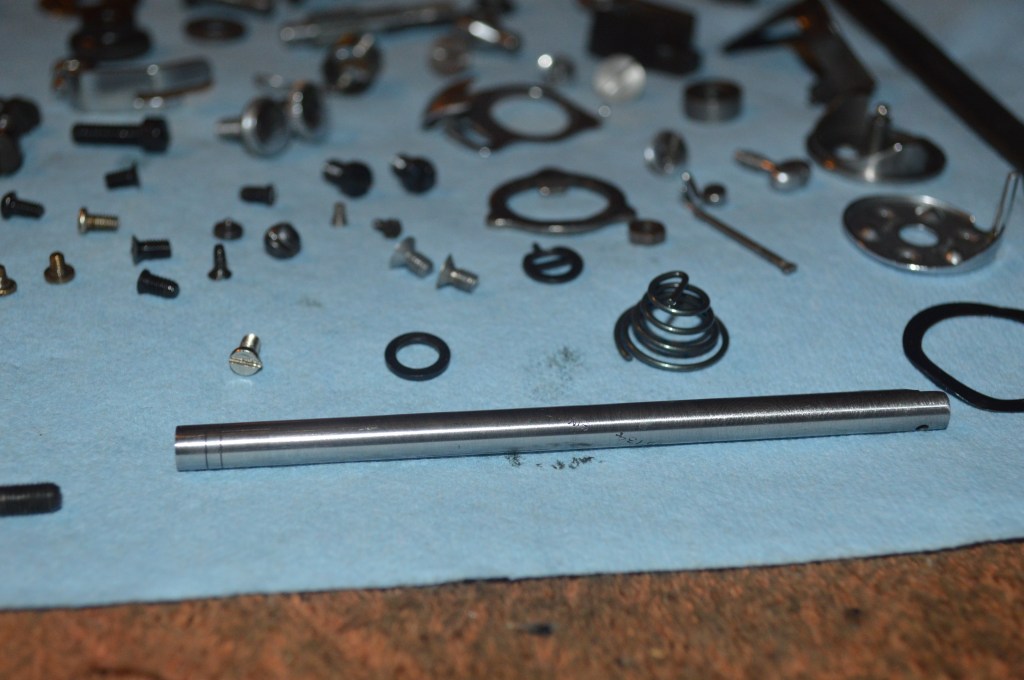

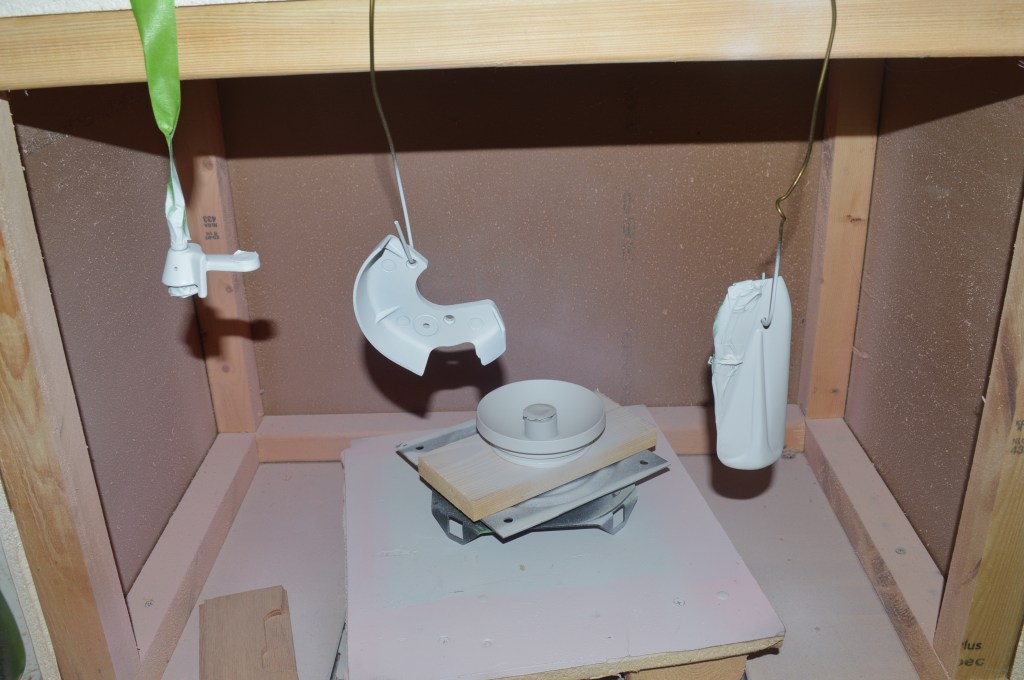

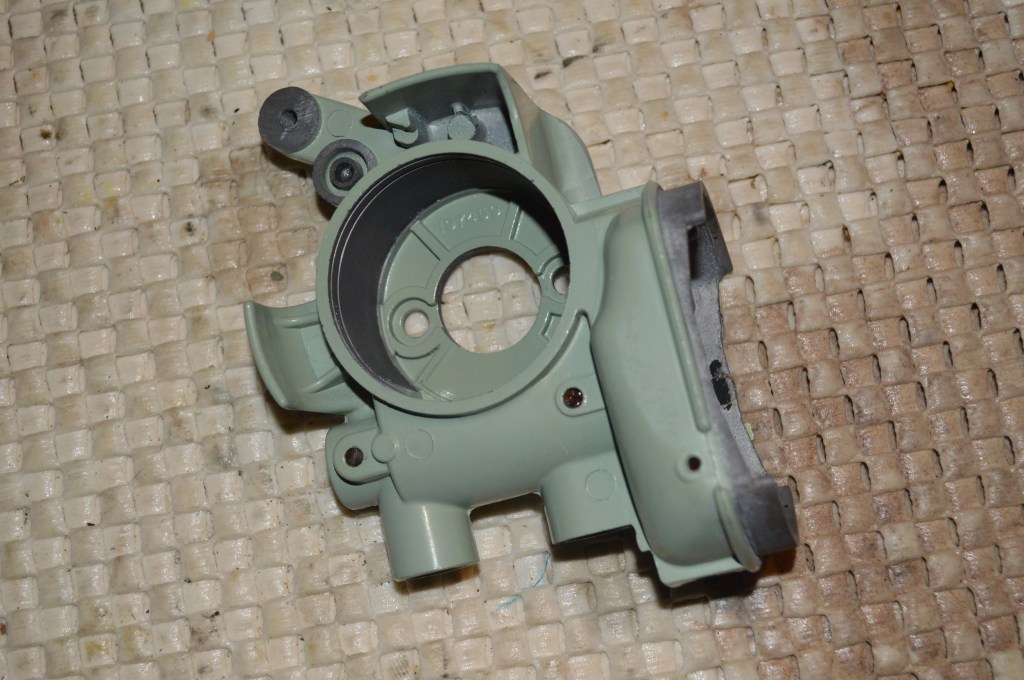

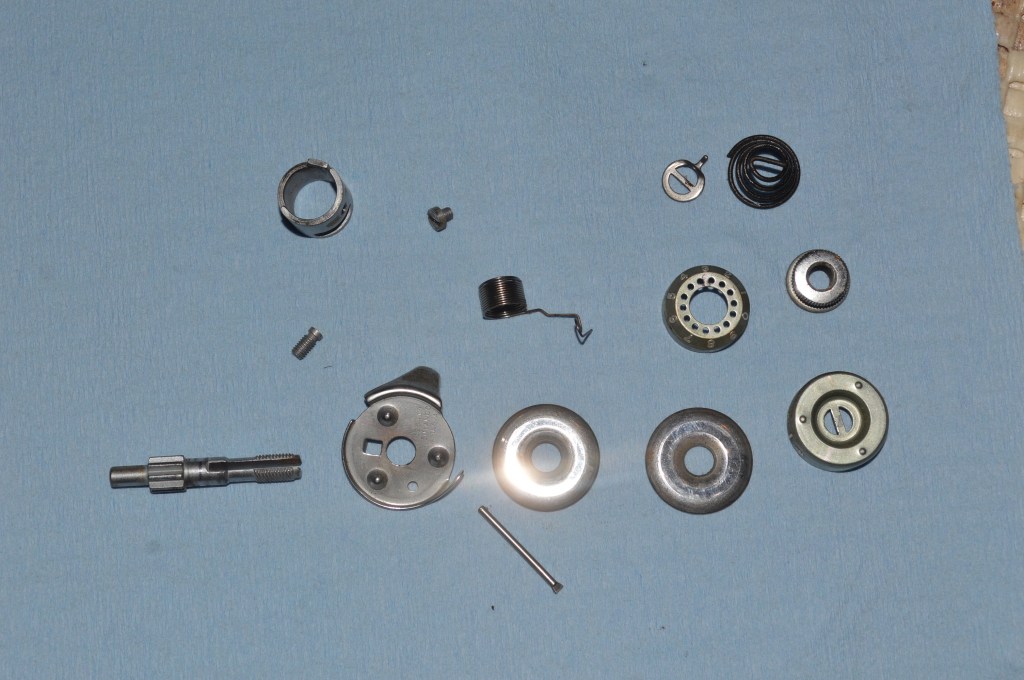

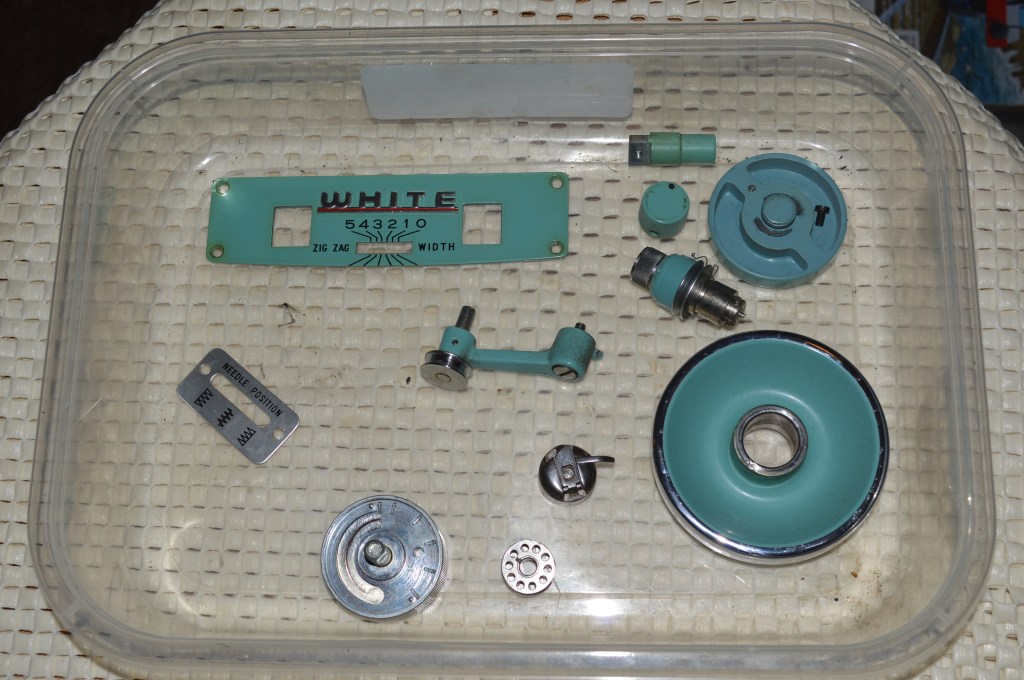

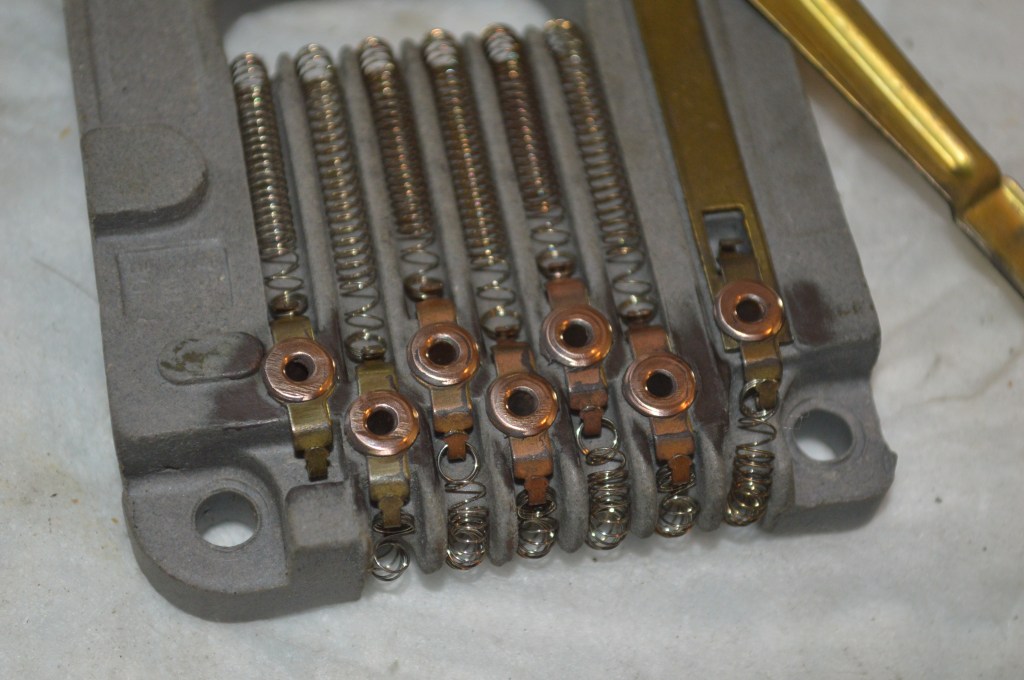

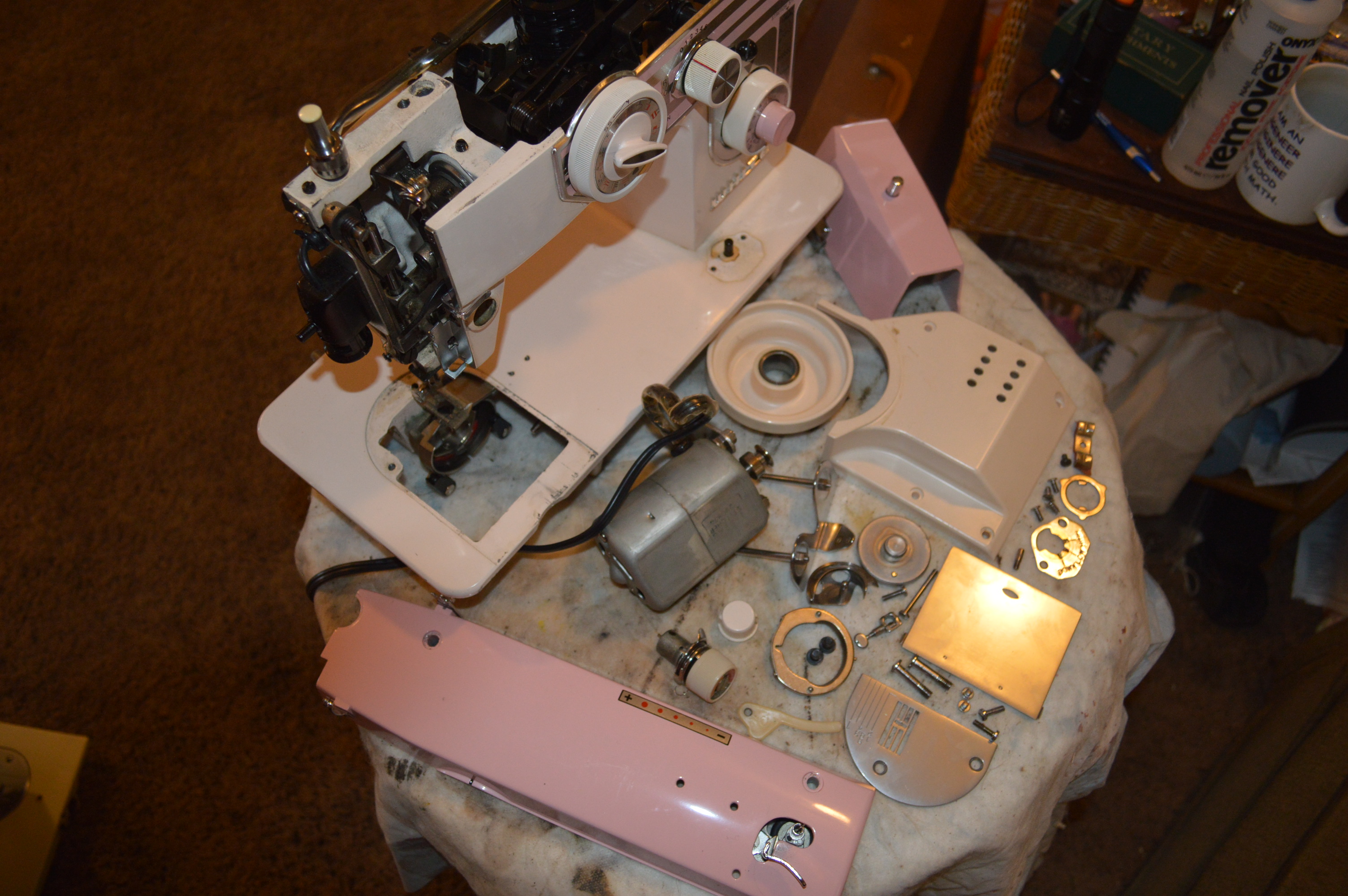

After disassembly, all of the parts are laid out for cleaning.

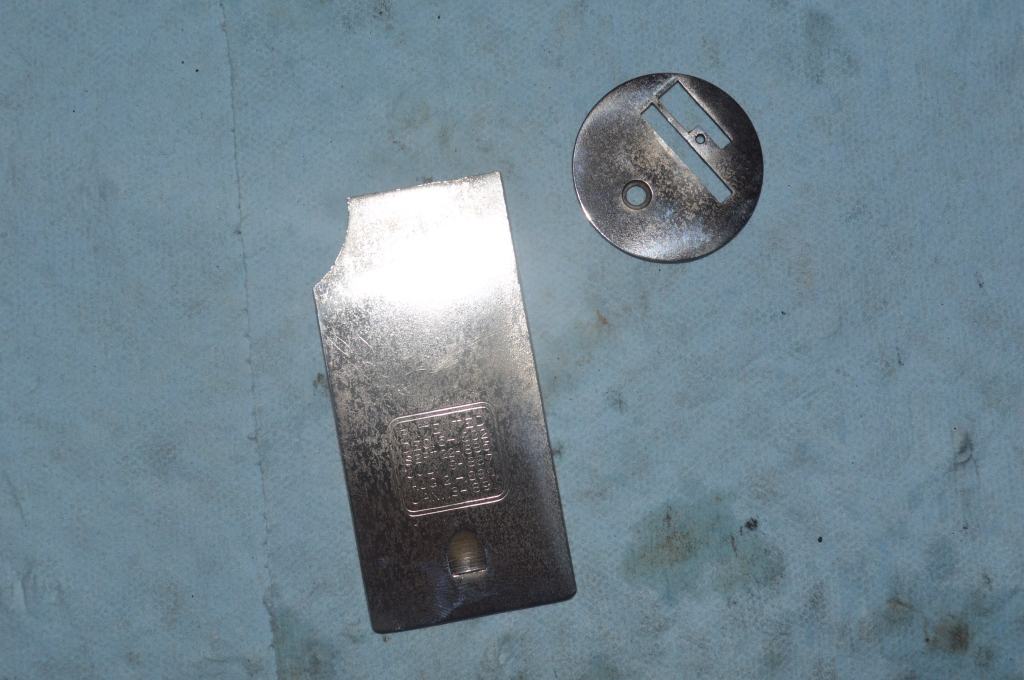

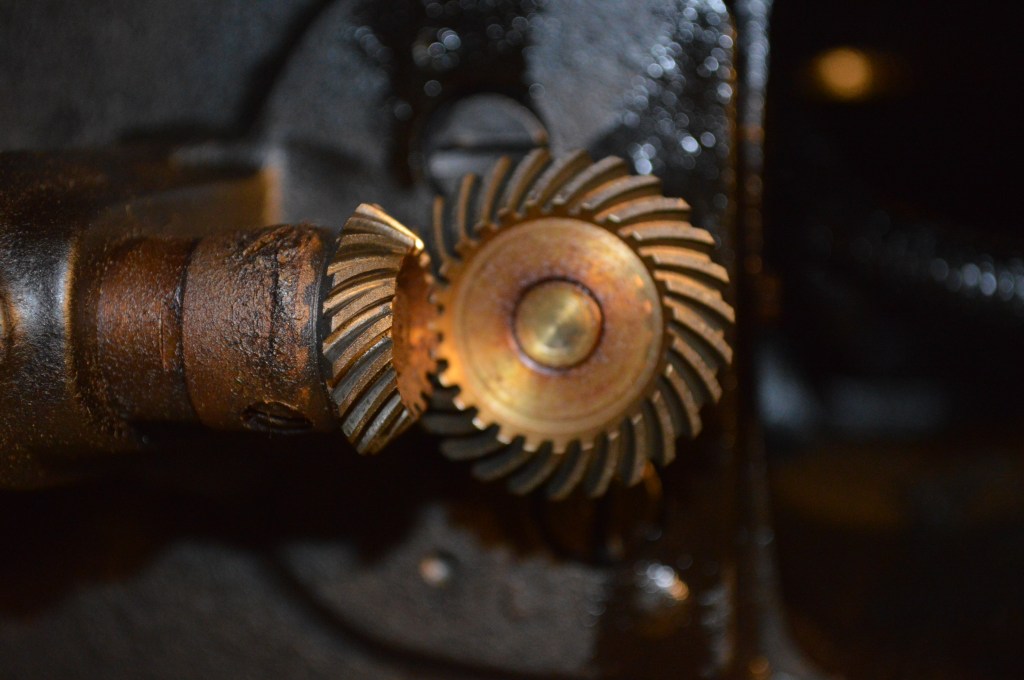

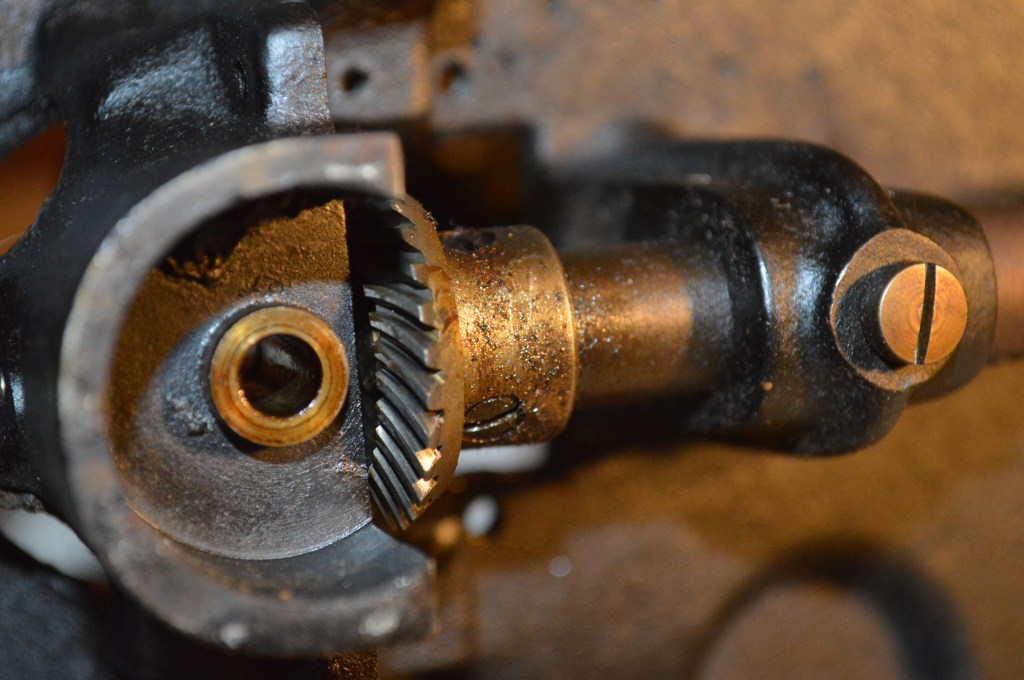

The parts are ultrasonically cleaned, heated in oil to 250 degrees to drive off water, and then each piece is wire brushed to shiny steel.

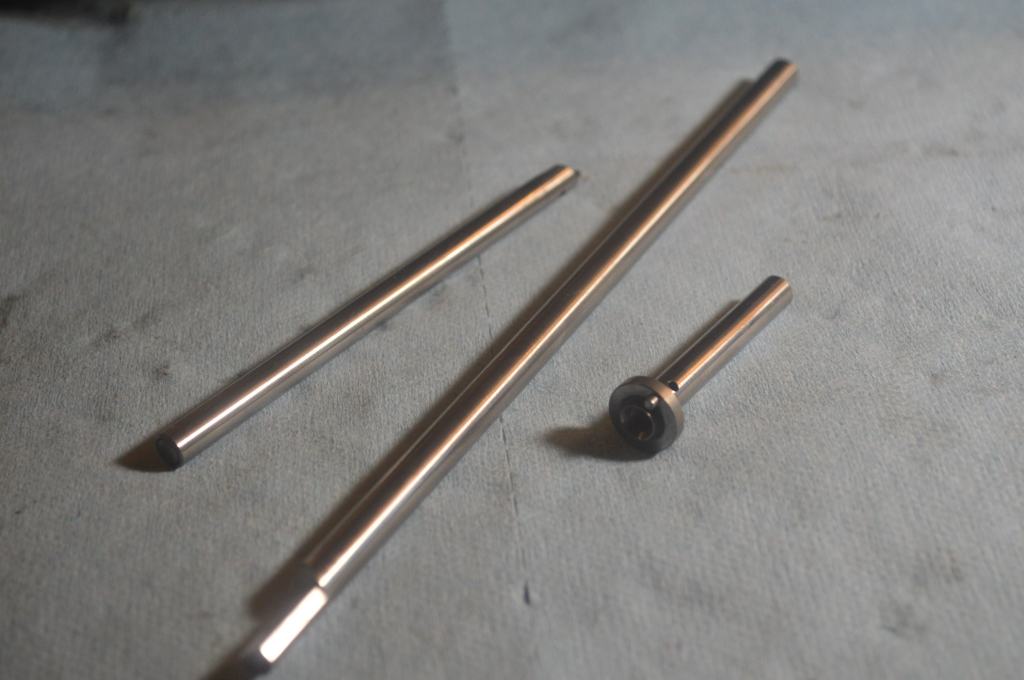

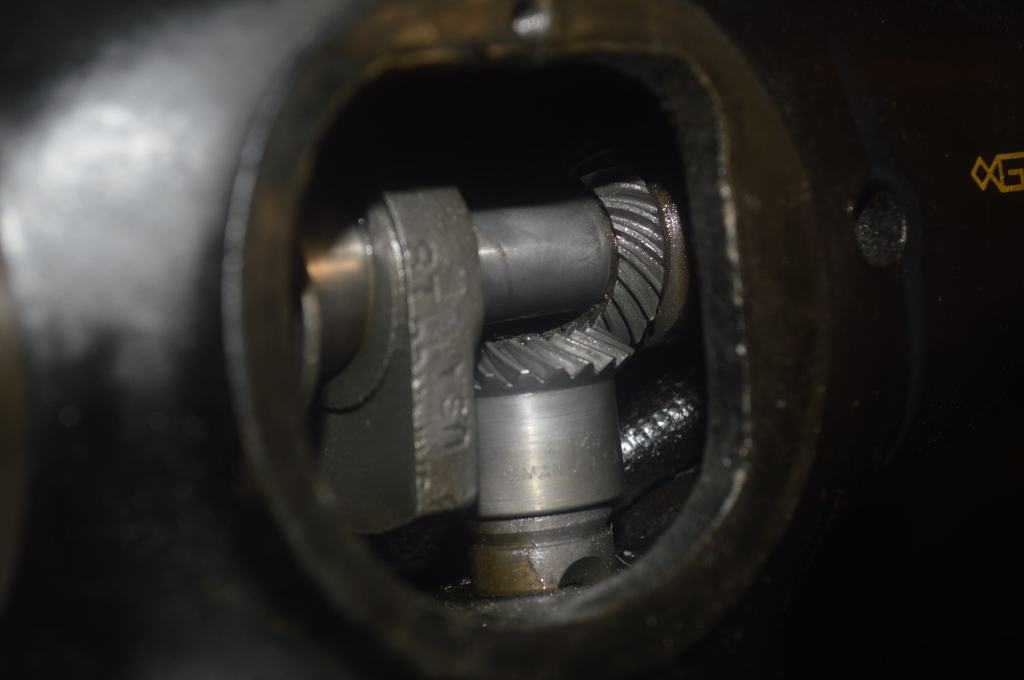

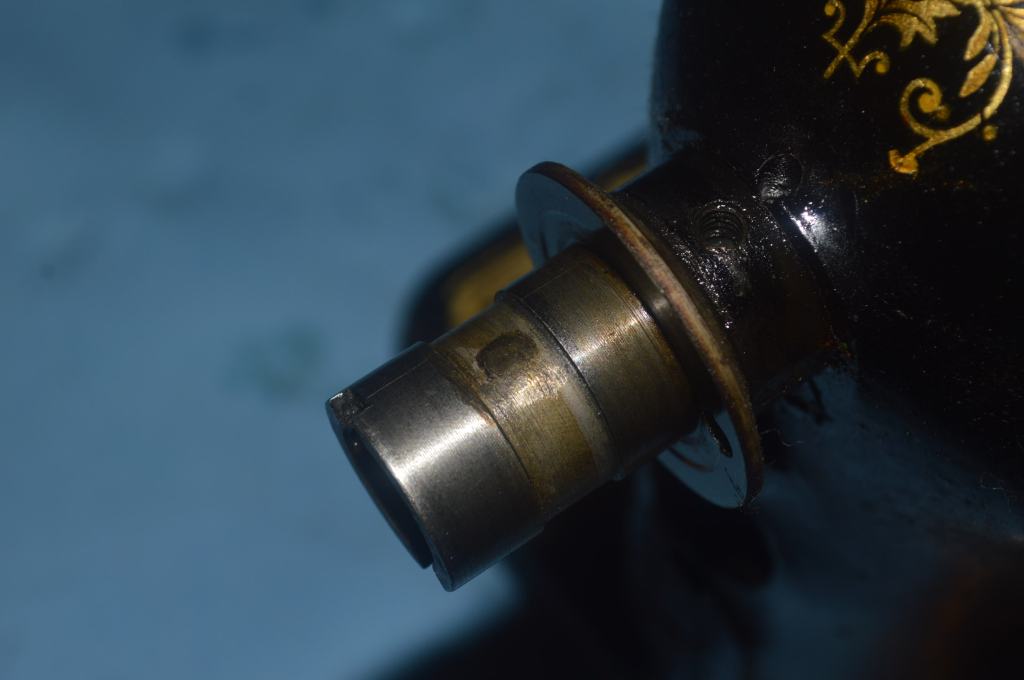

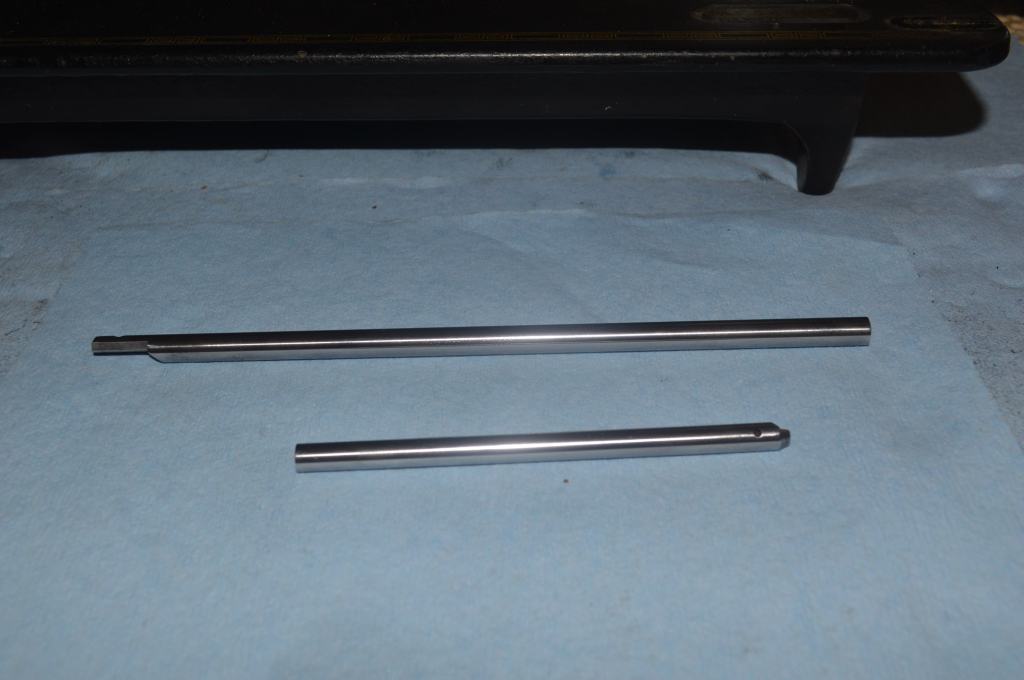

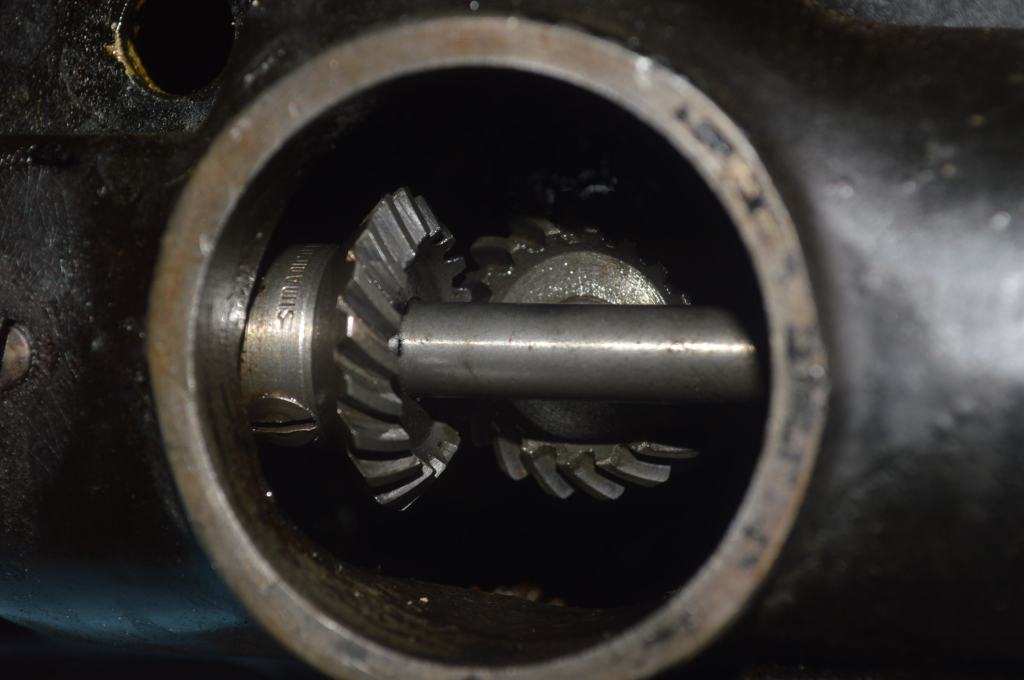

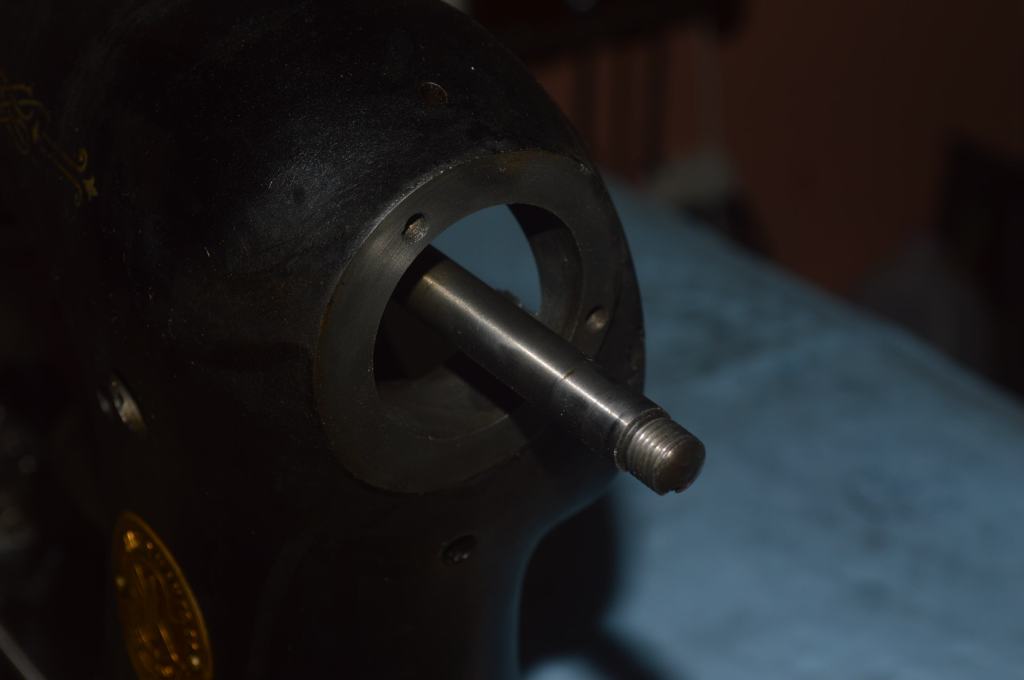

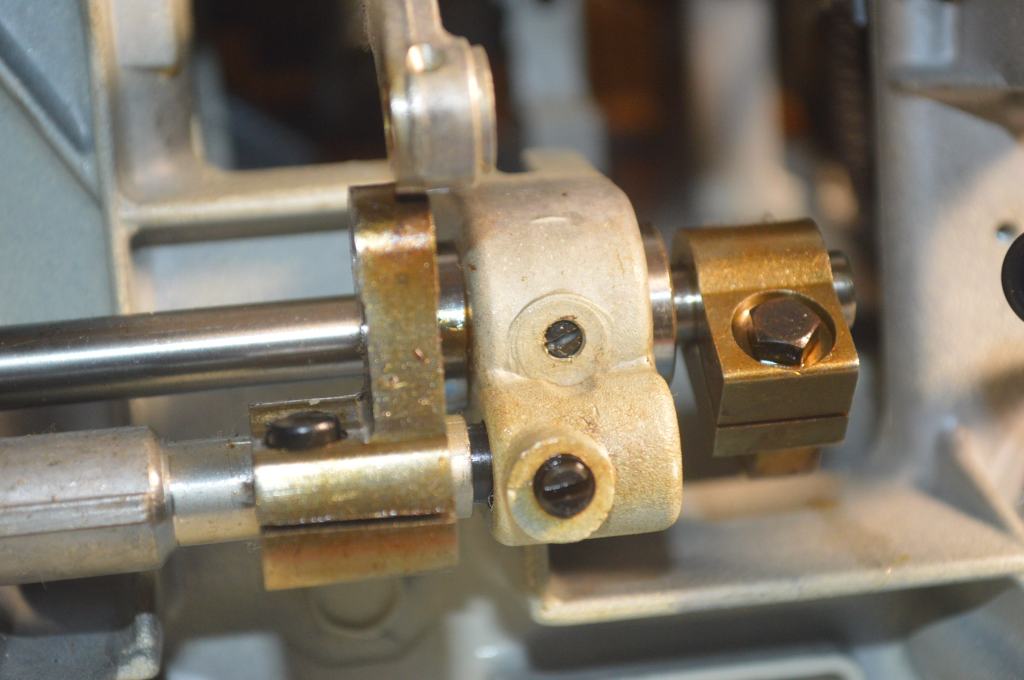

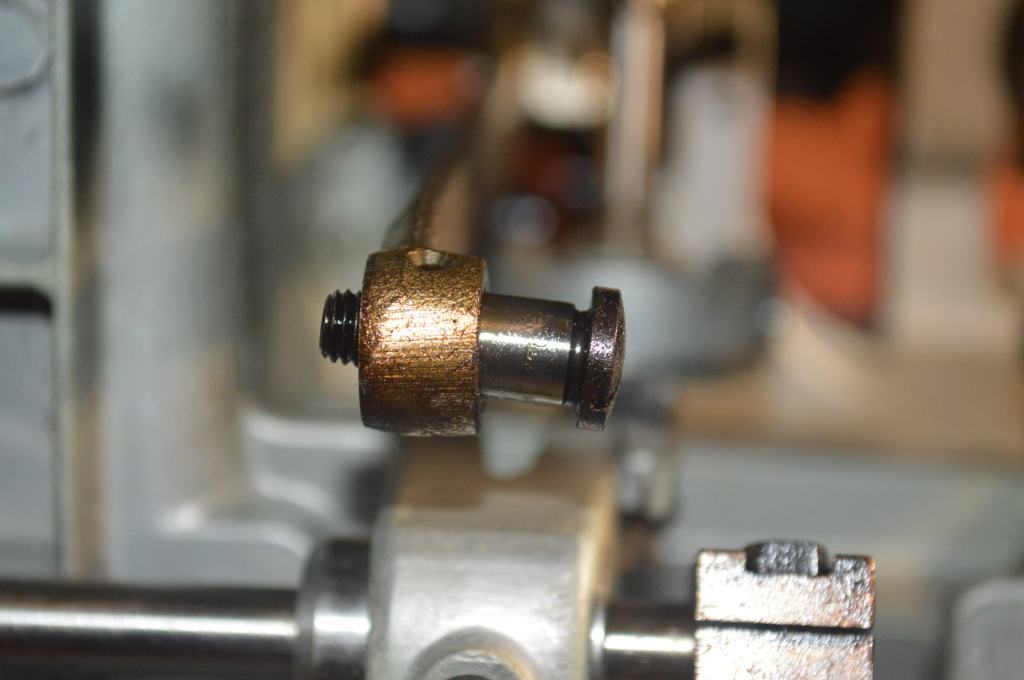

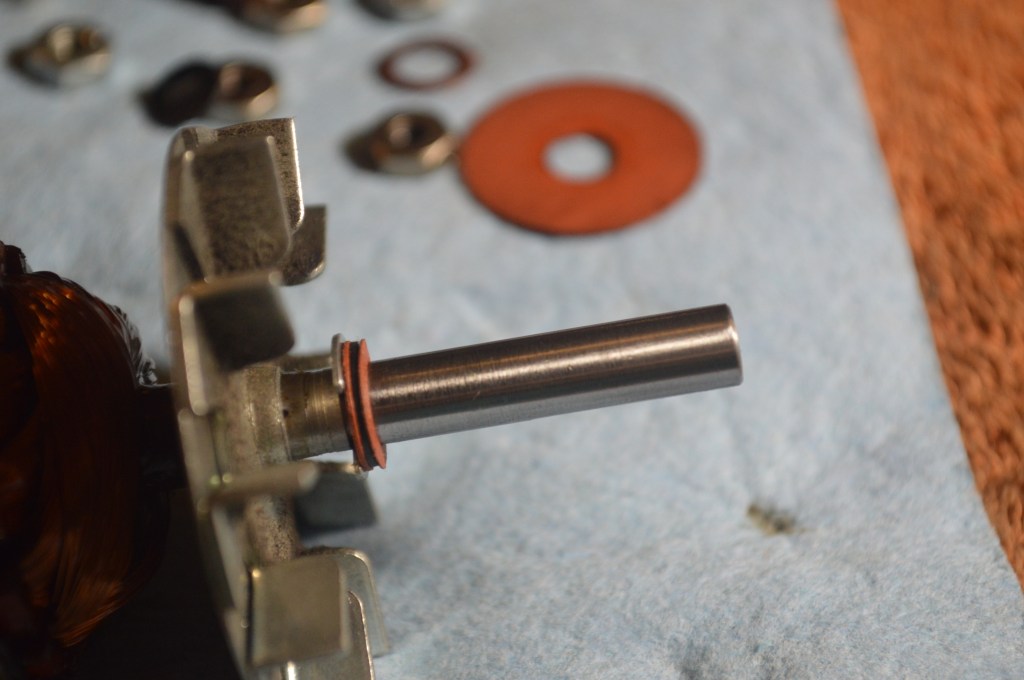

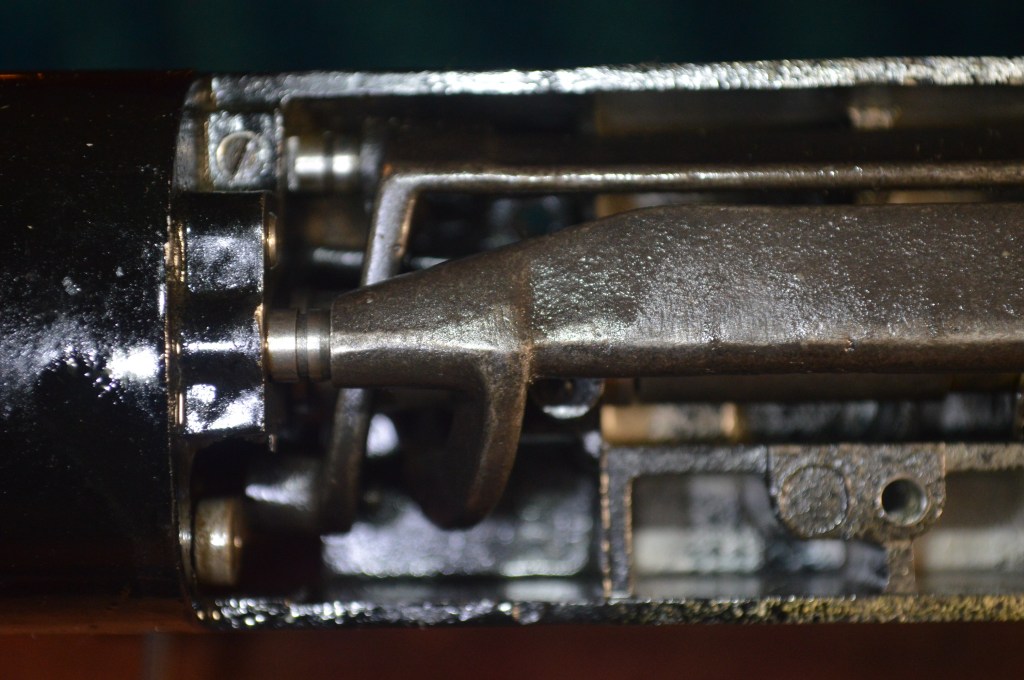

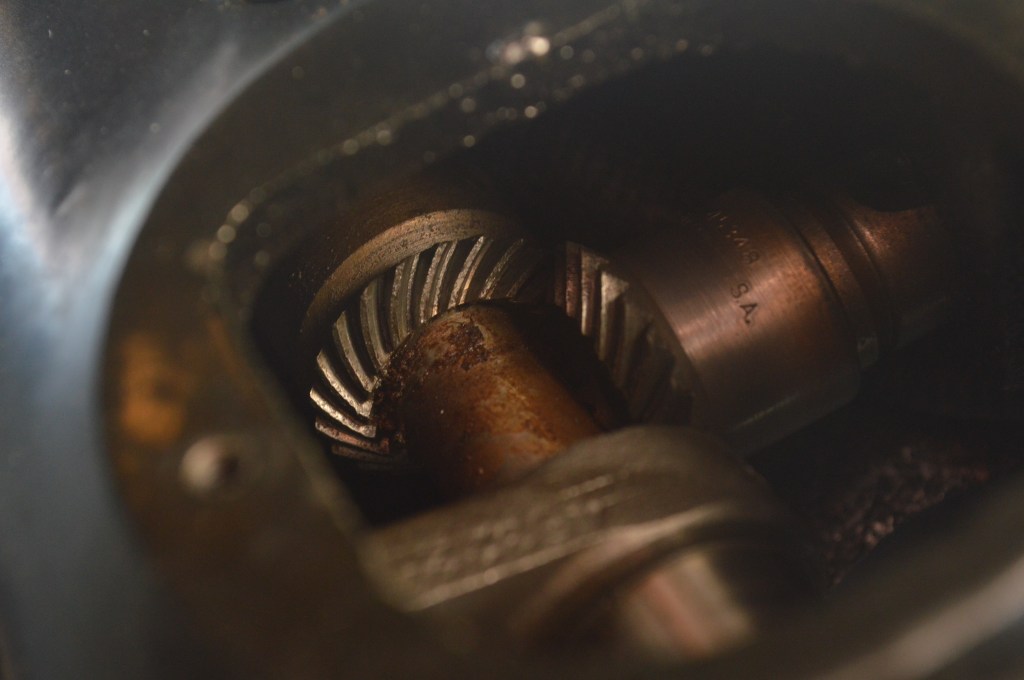

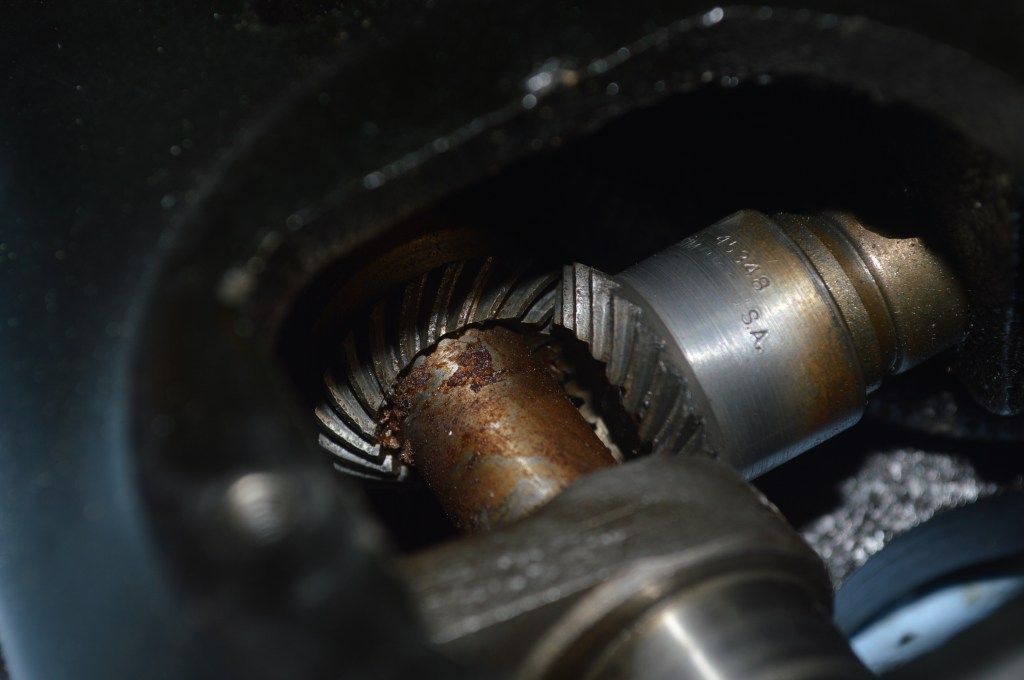

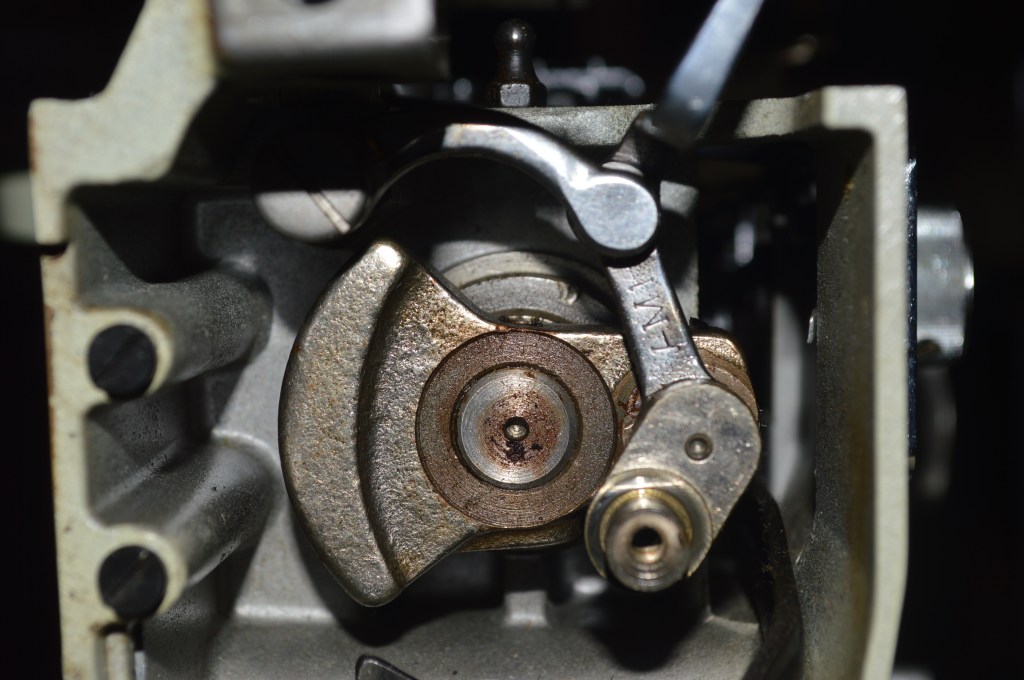

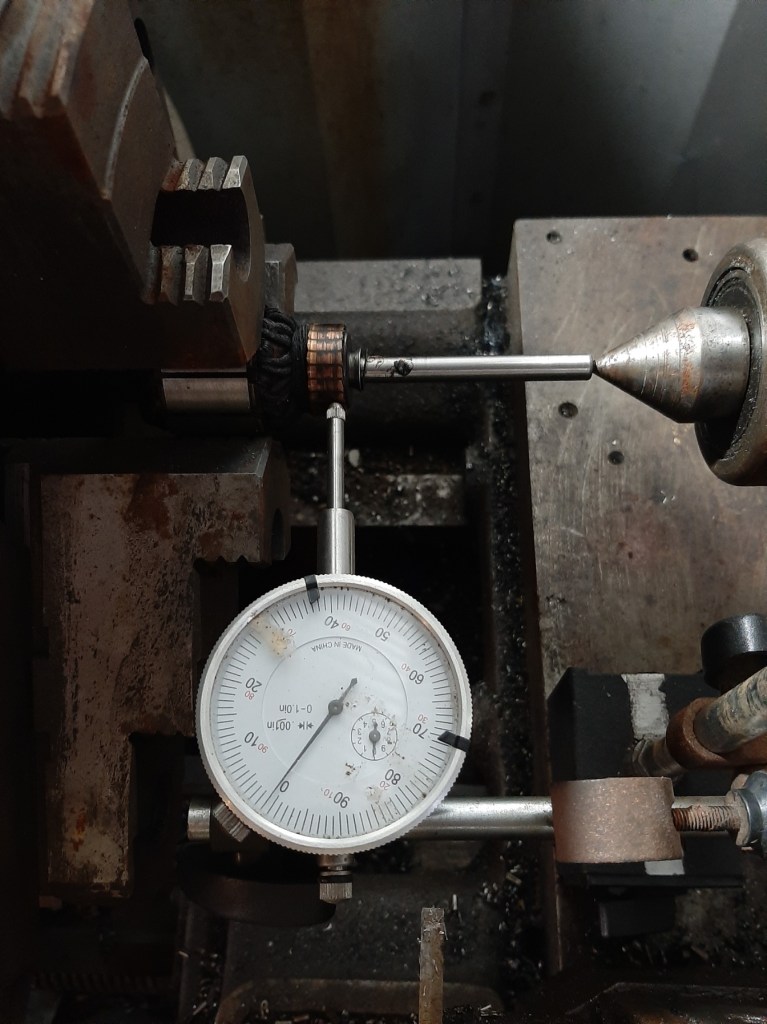

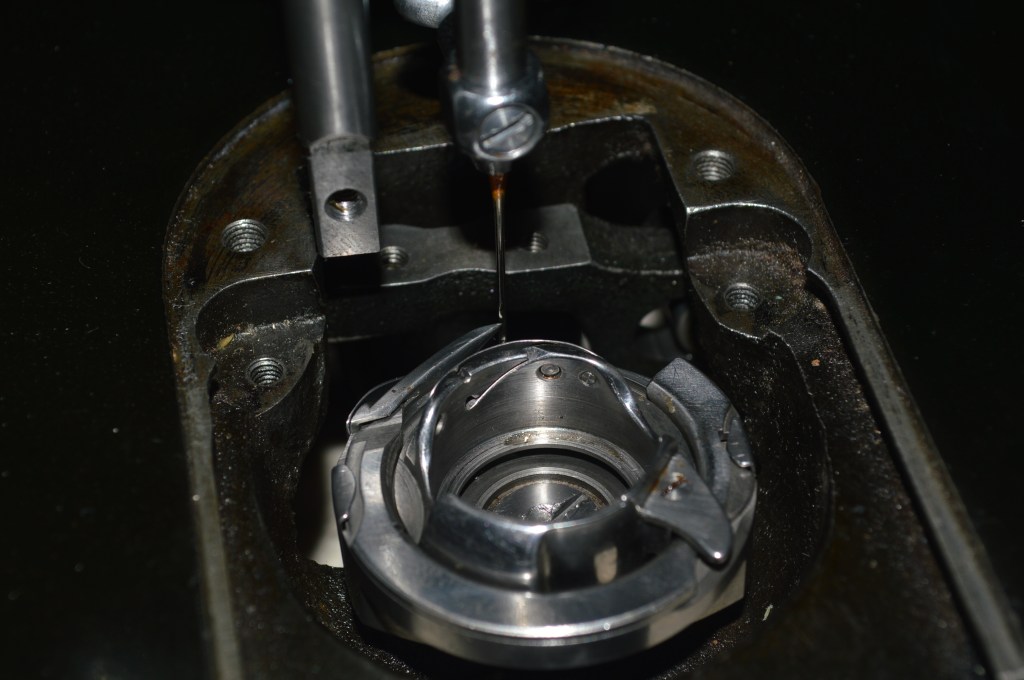

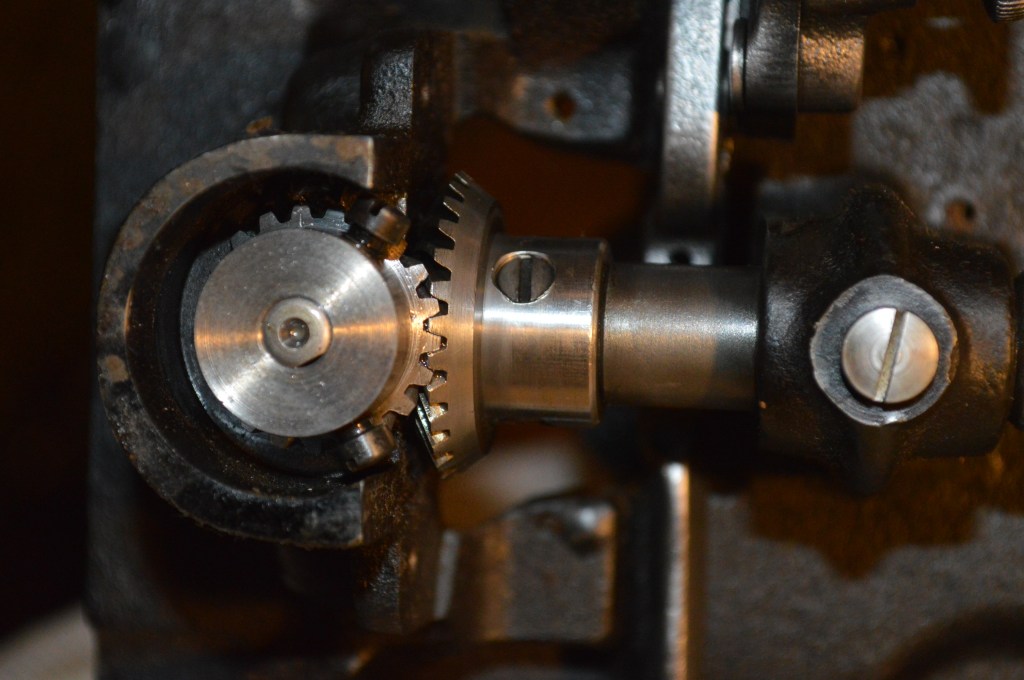

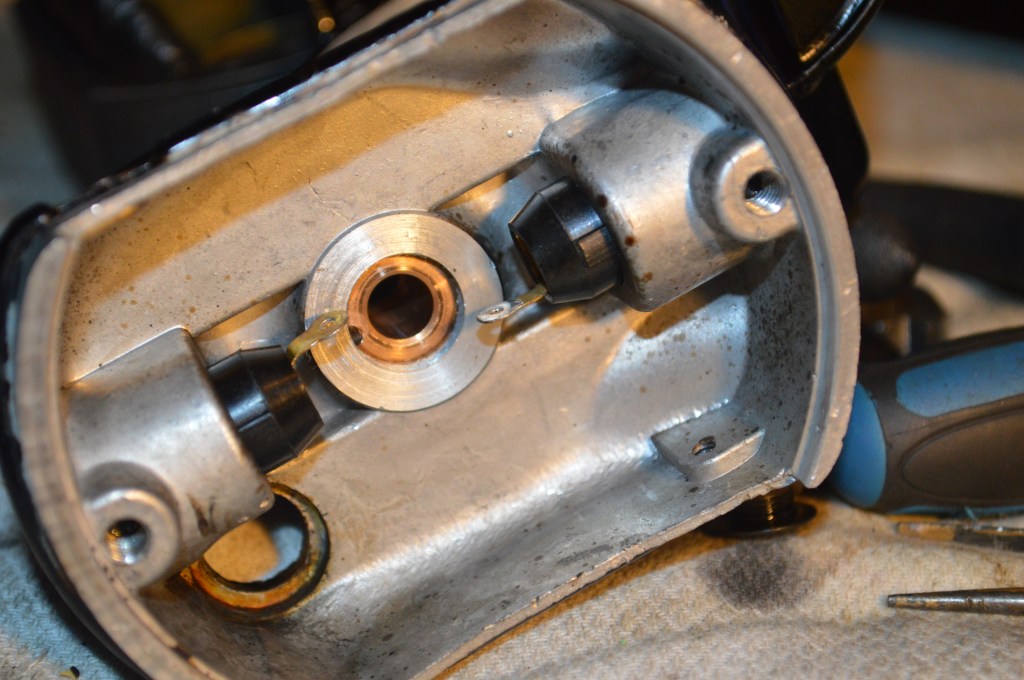

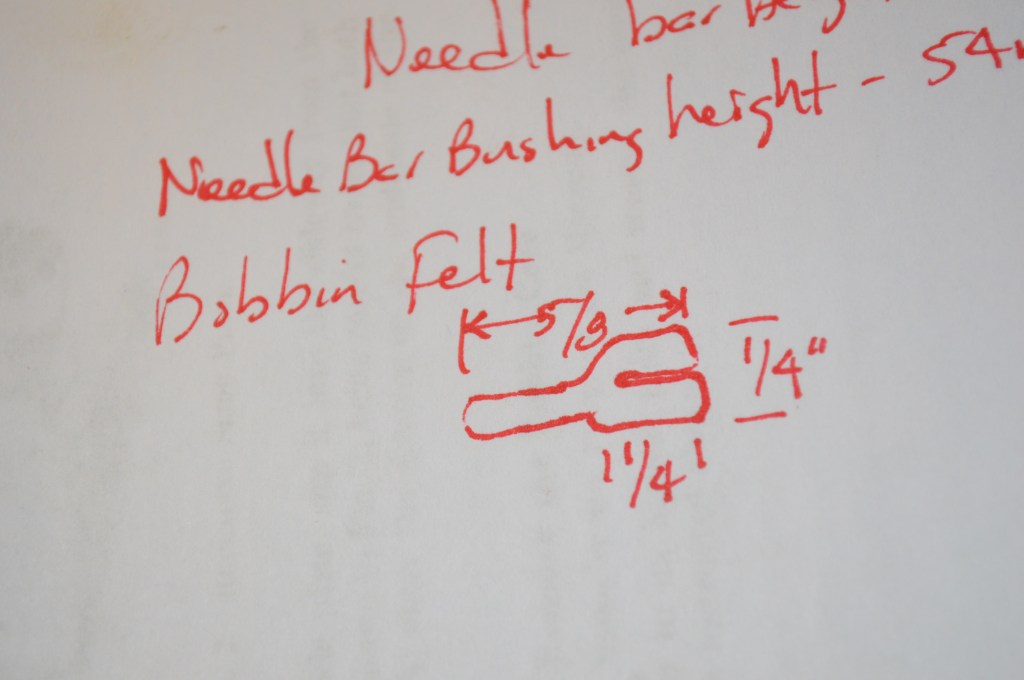

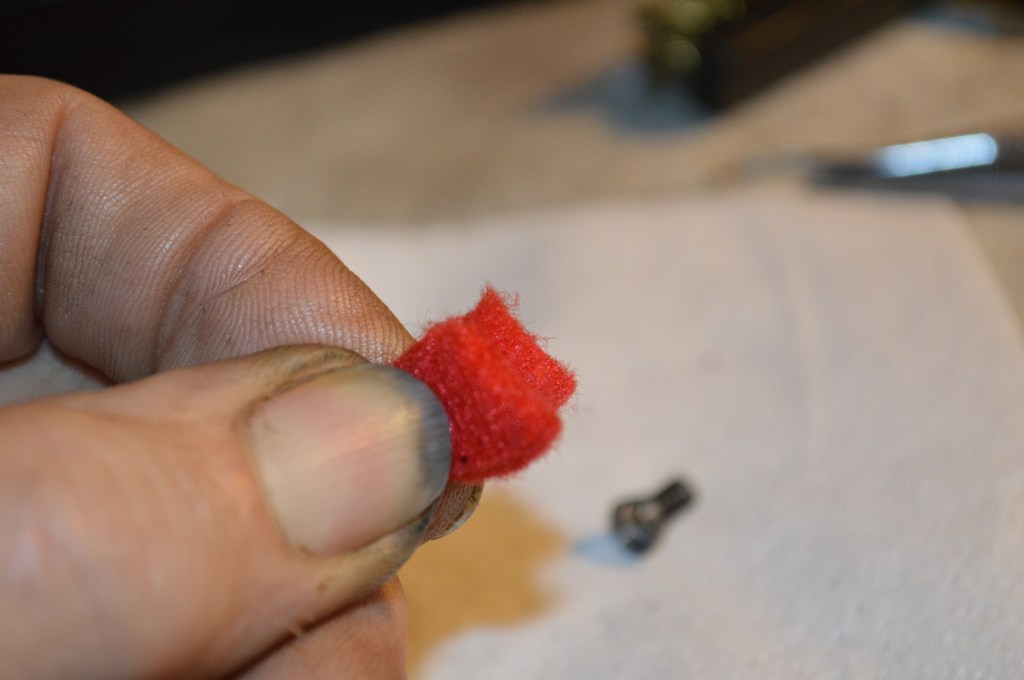

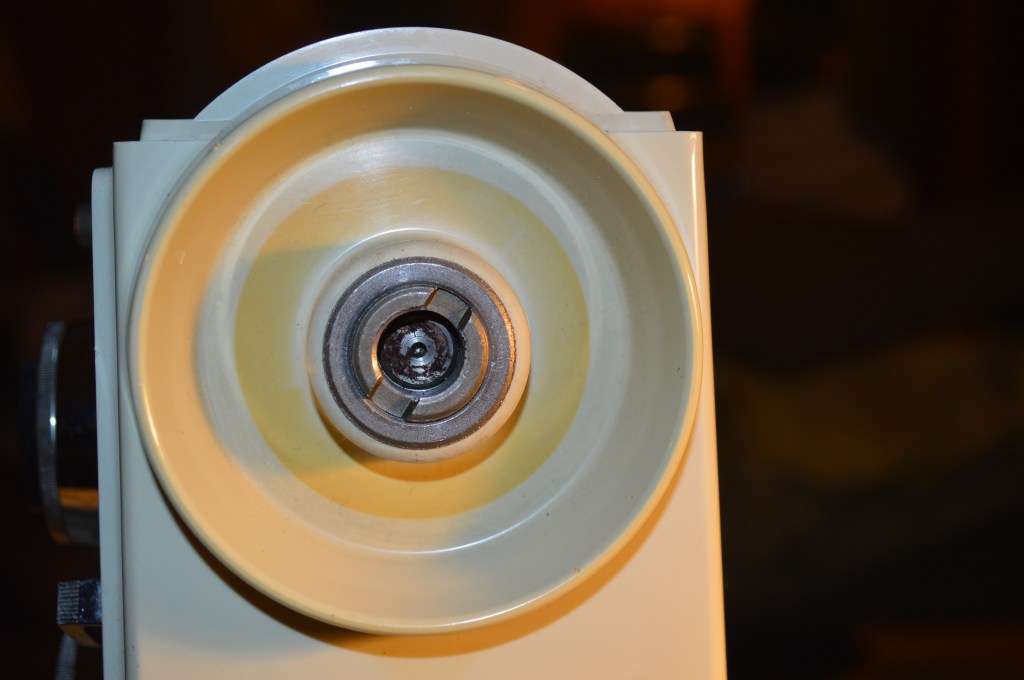

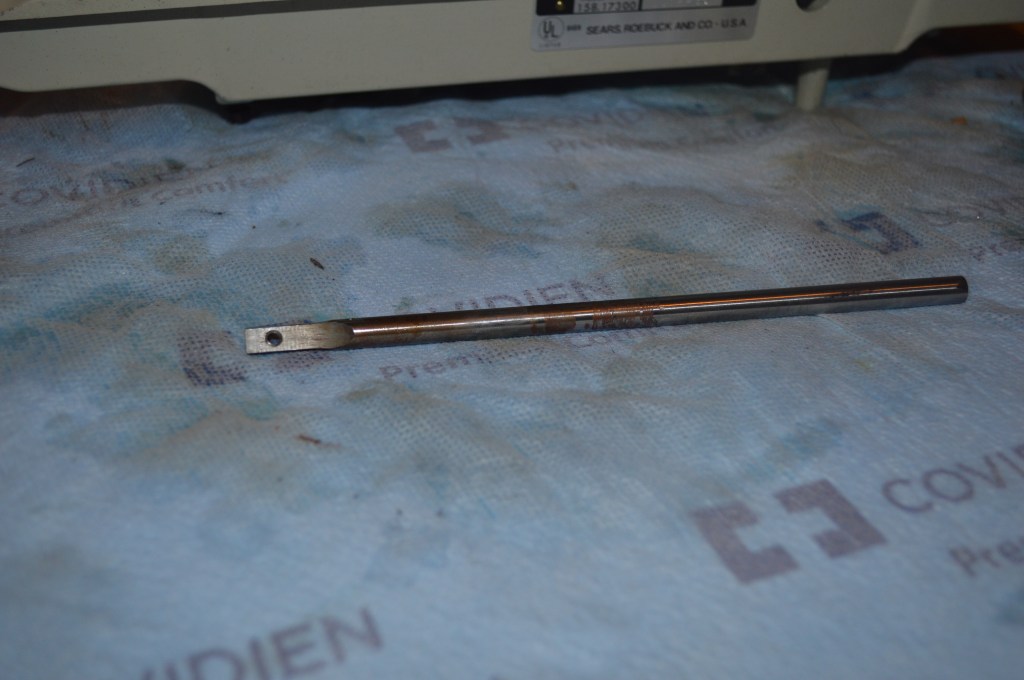

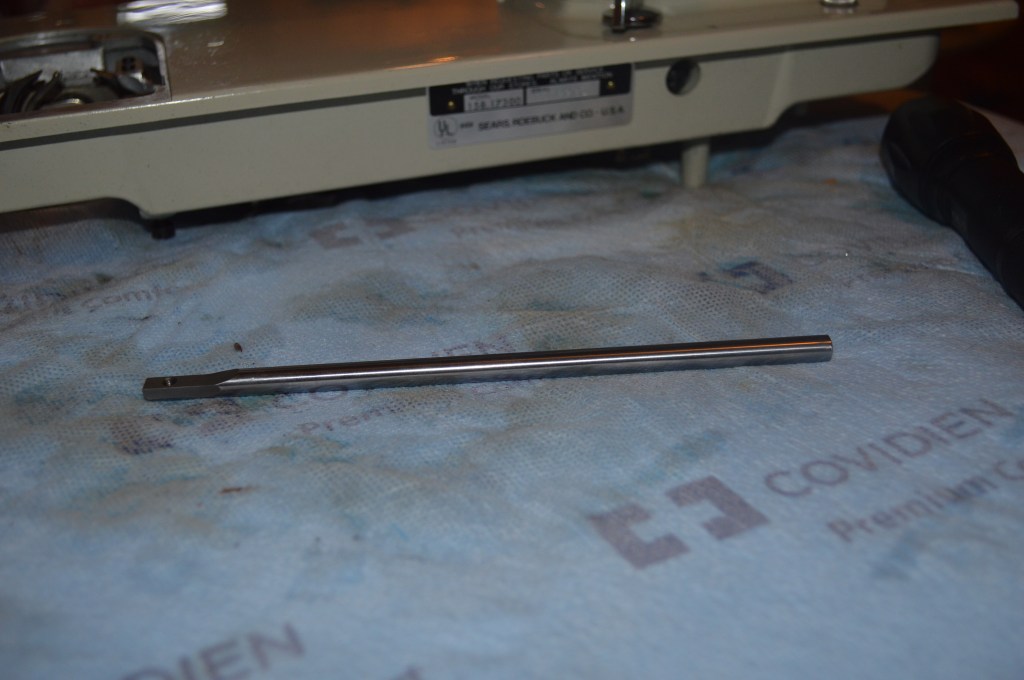

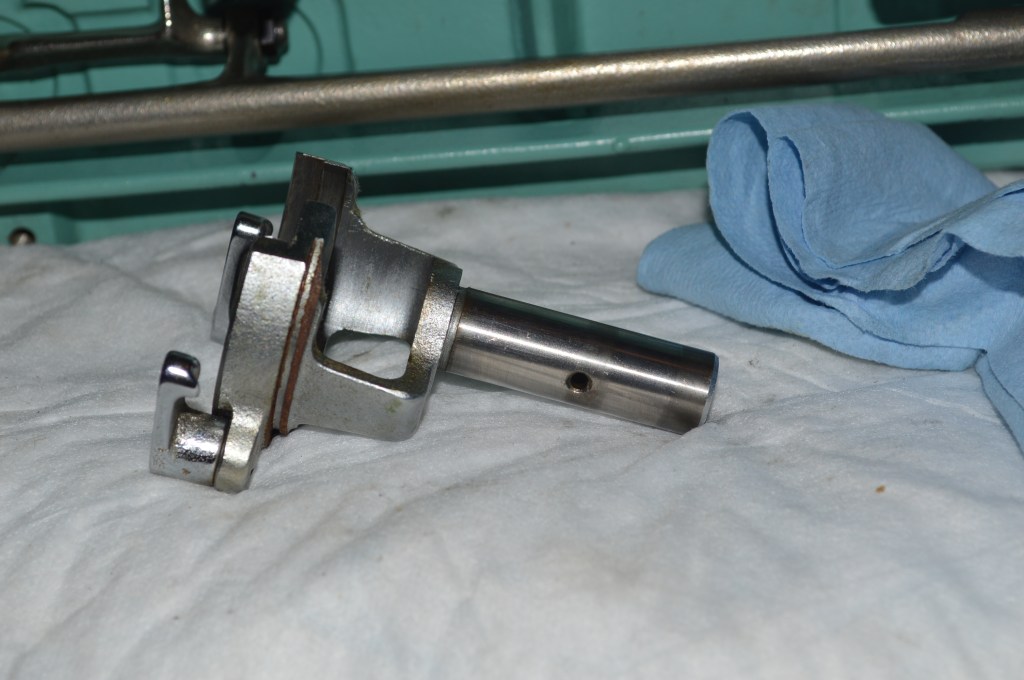

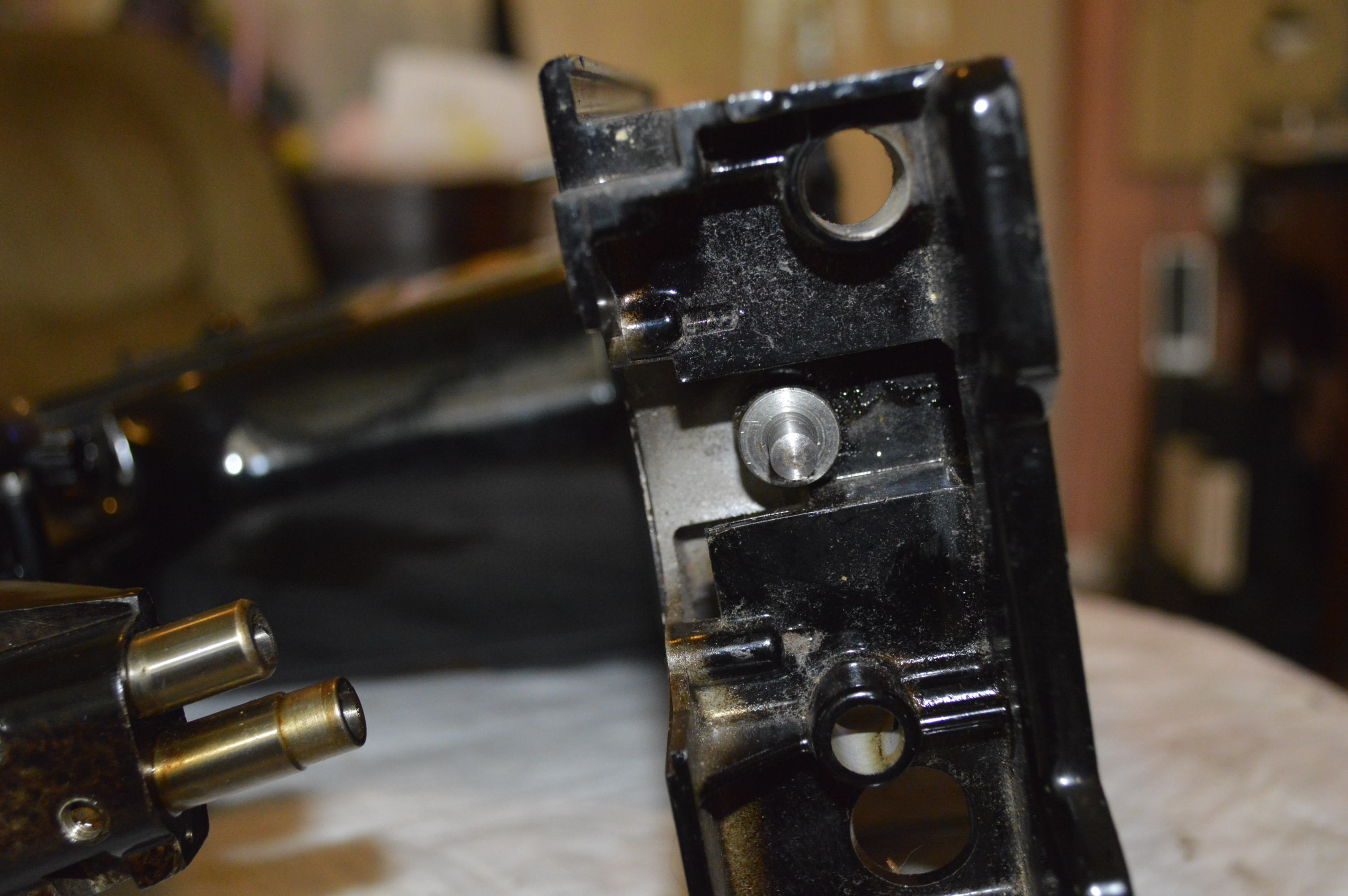

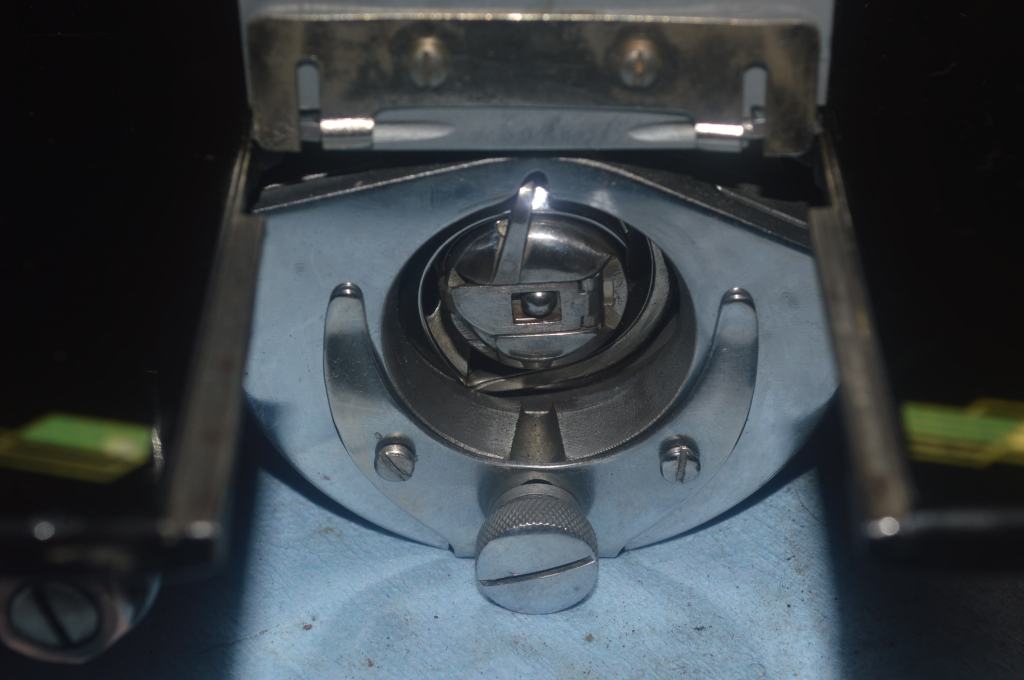

The needle bar, presser foot bar, and bottom bobbin hook shaft are polished to a glass smooth finish.

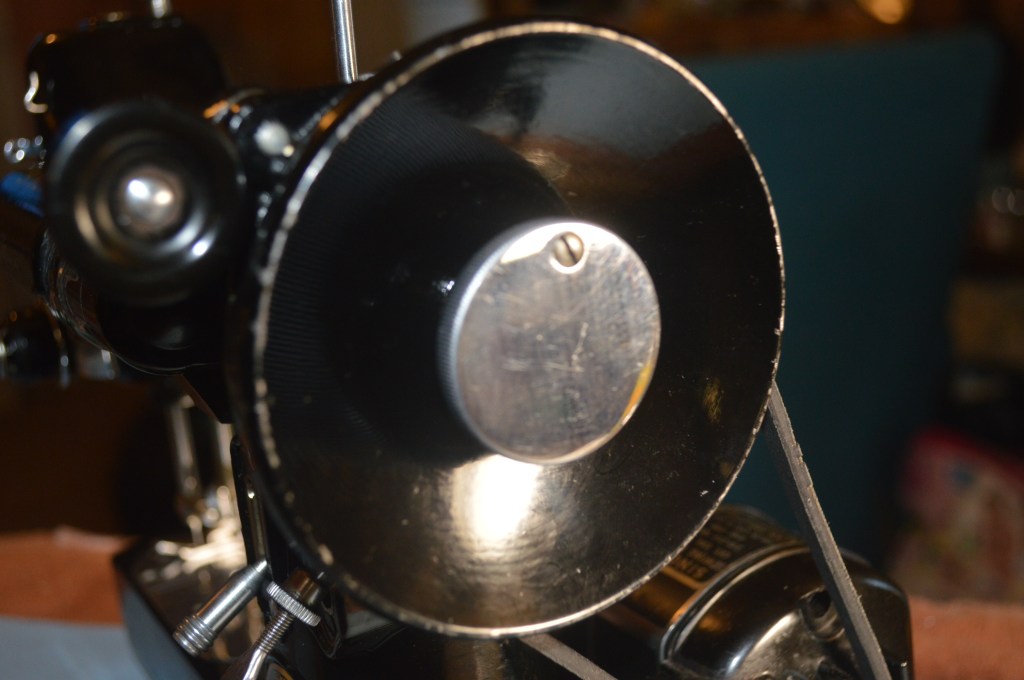

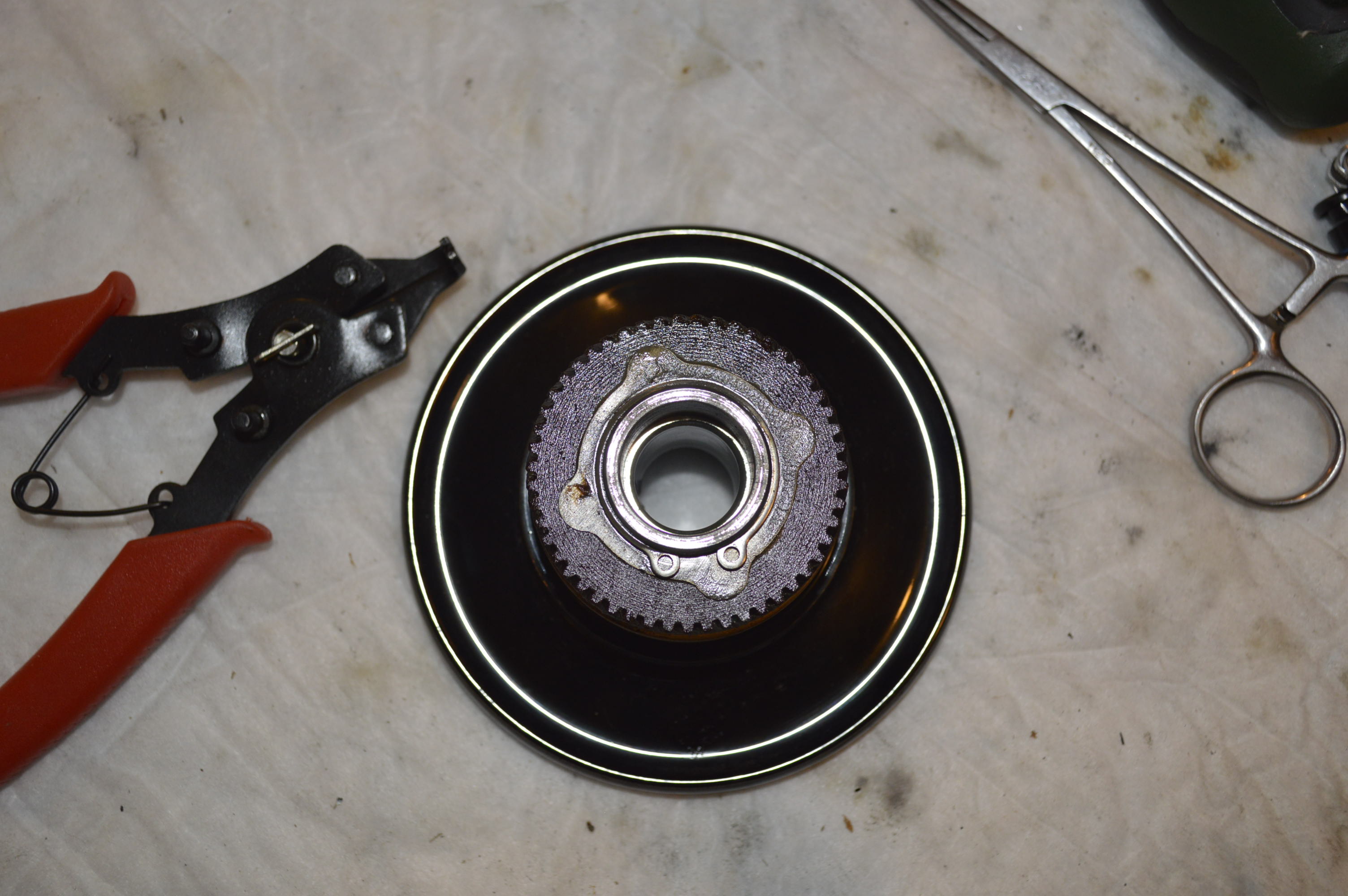

Because of the abundance of plated parts, they are polished too.

All of the plated pieces are going to be polished anyway, but now is a great opportunity polish some of the parts and get ahead for the reassembly.

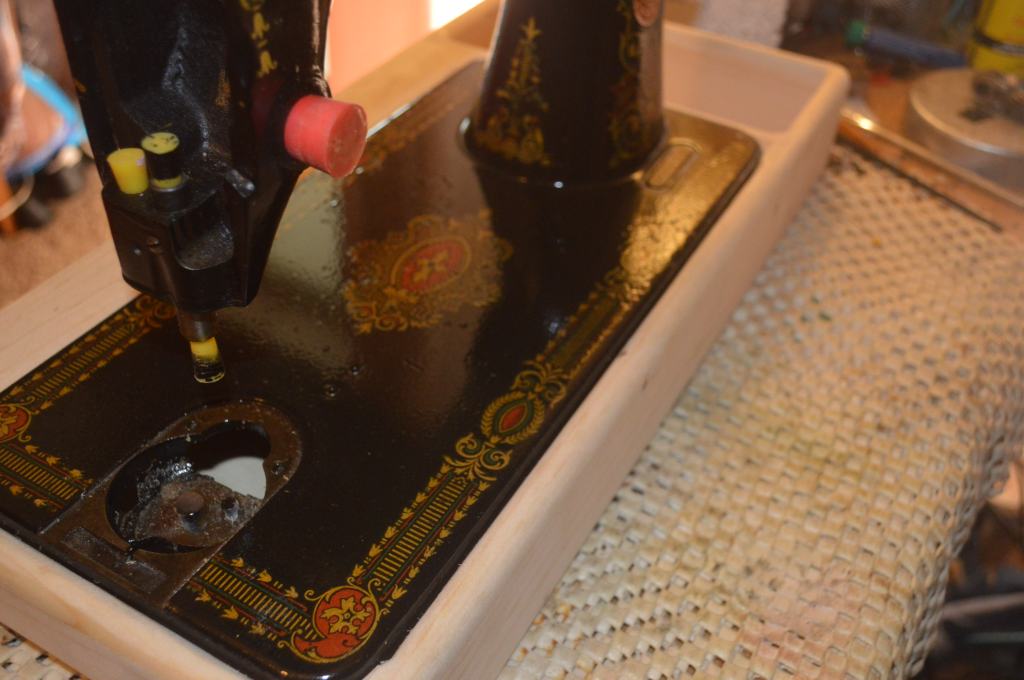

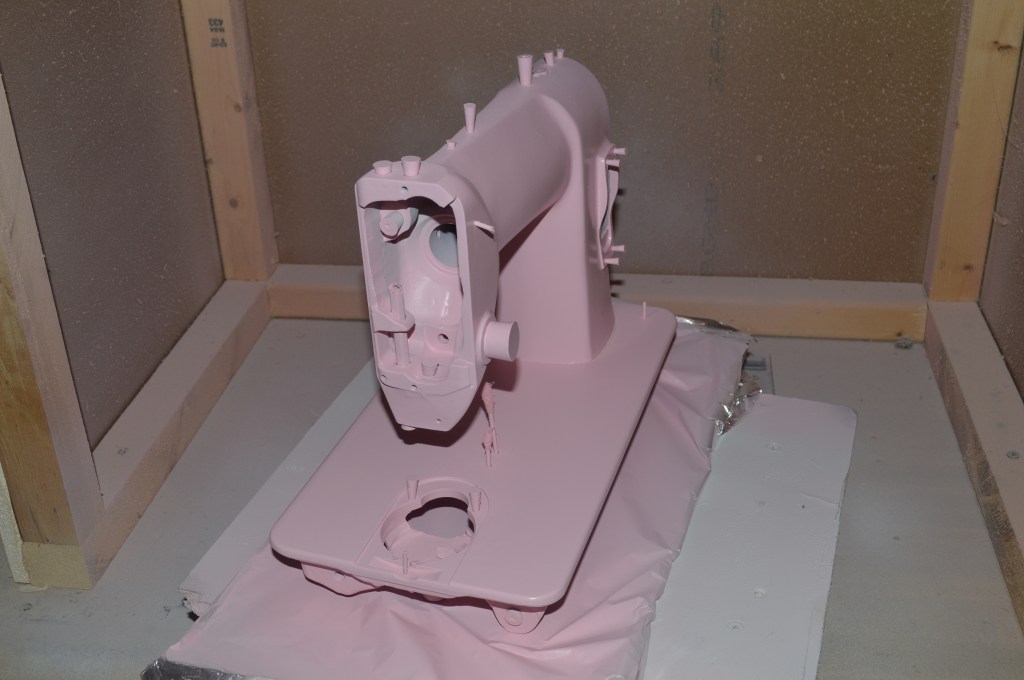

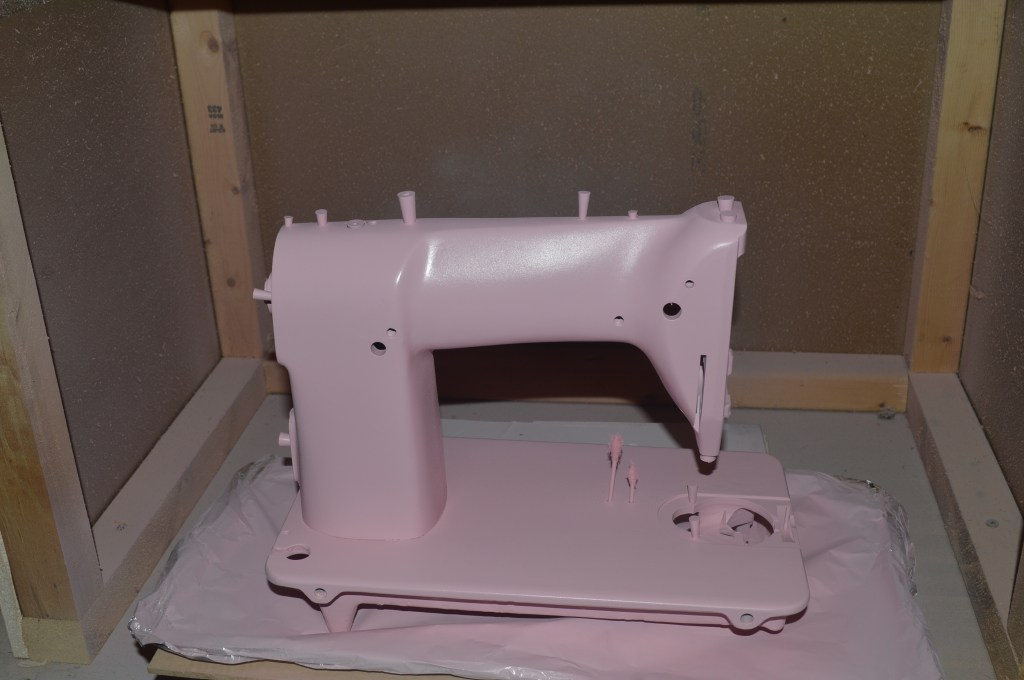

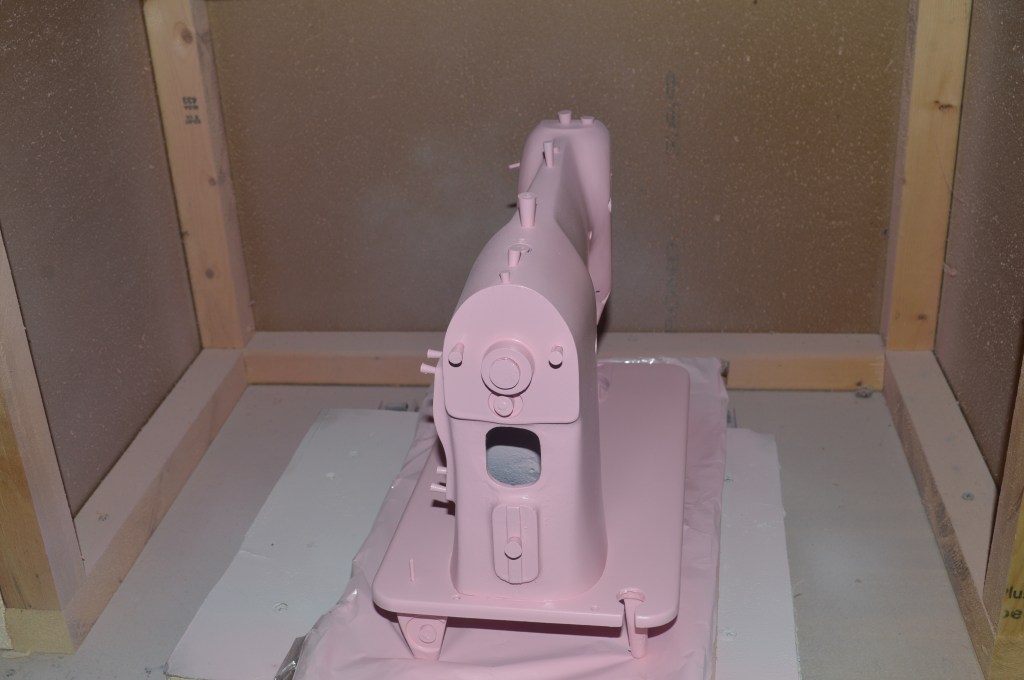

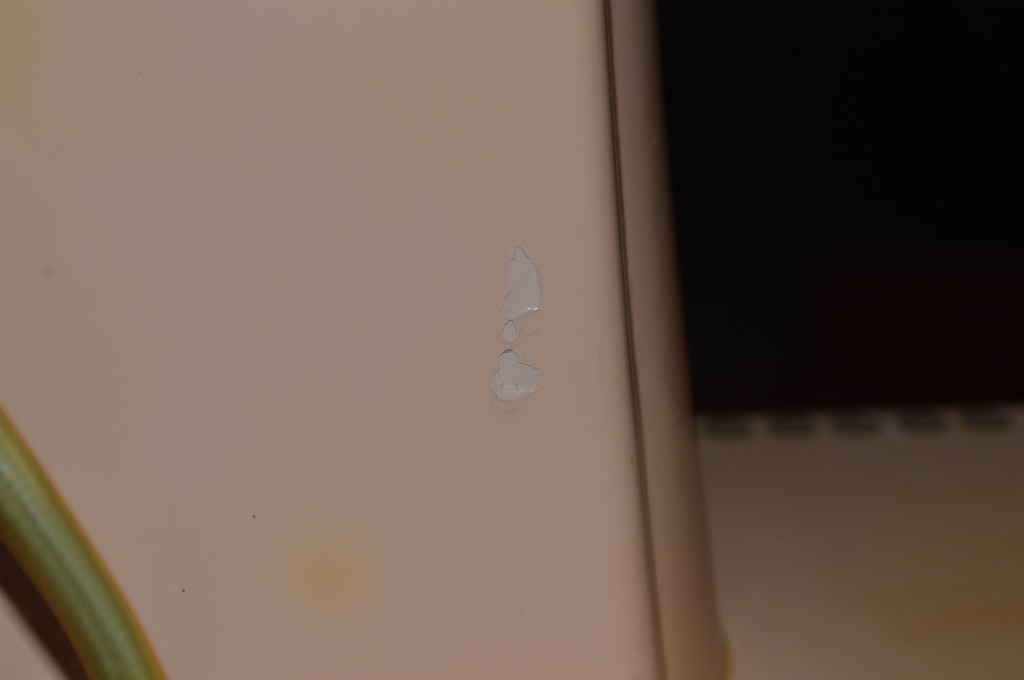

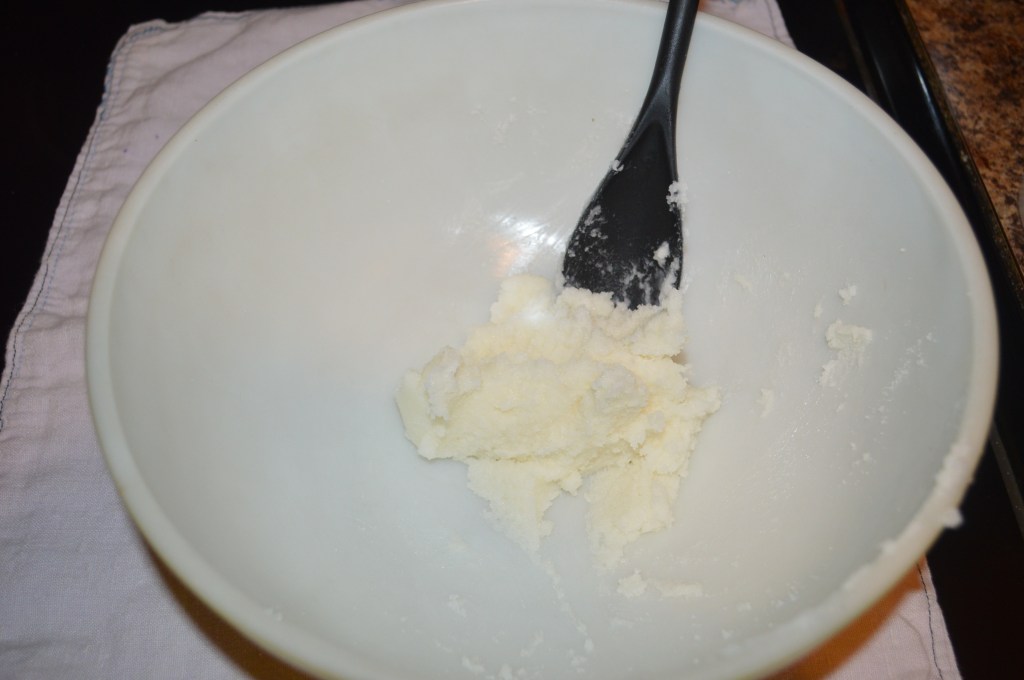

While all of this has been going on, I have been working on the paint repairs. The bed edge chips are easy. The scars and the large chips on the bed are not.

The bed chips are easily repaired.

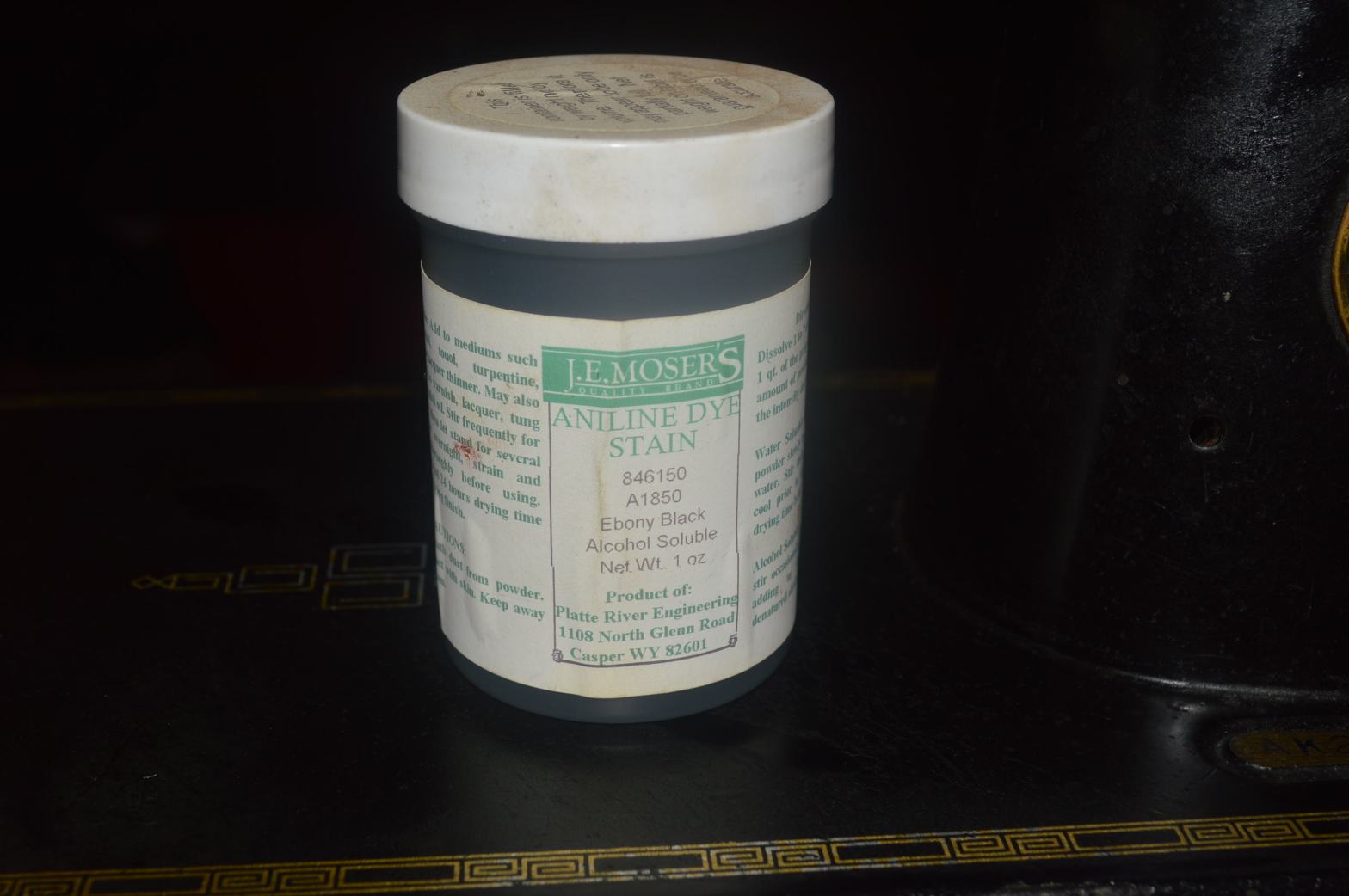

The other repairs are a challenge. The bed chips need to be filled and then rubbed out flush to the bed. This required eight applications of paint to fill the chip, sanding the repair flush with the bed, and then glase polishing to complete the repair. Each application was allowed to dry for one day before the next was applied. There is no rush though, there is plenty to do.

The paint scar on the sewing machine arm is another story.

It can’t be filled, so paint is applied in two coats to the borders and then feathered as best I can to hide the repair.

There are a few other chips here and there, but they are fixed as they are found. All in all, it is a great outcome!

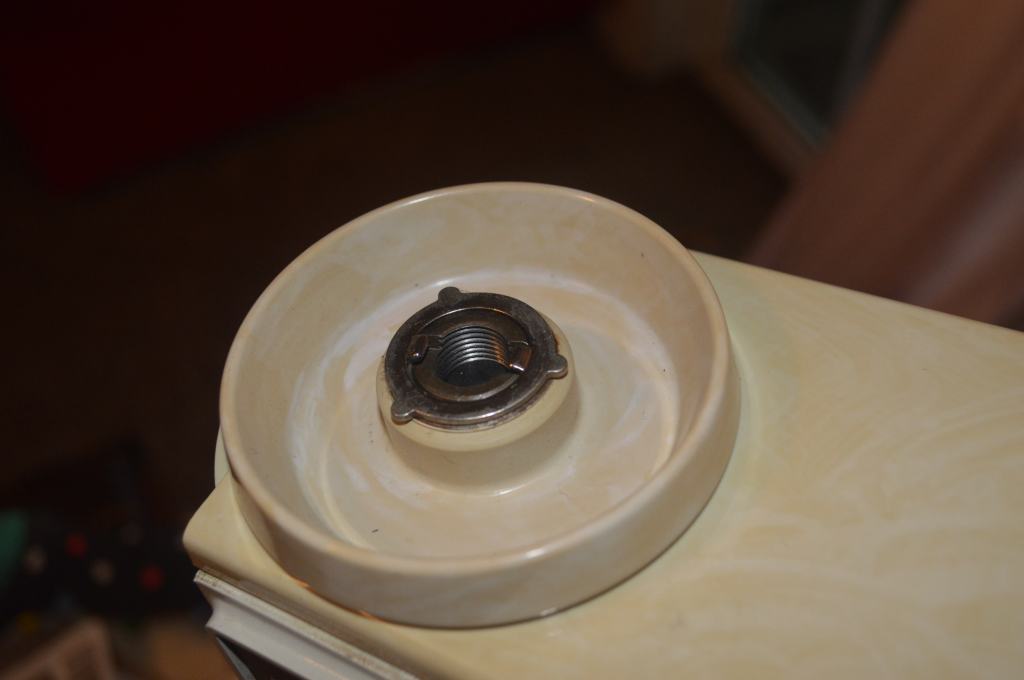

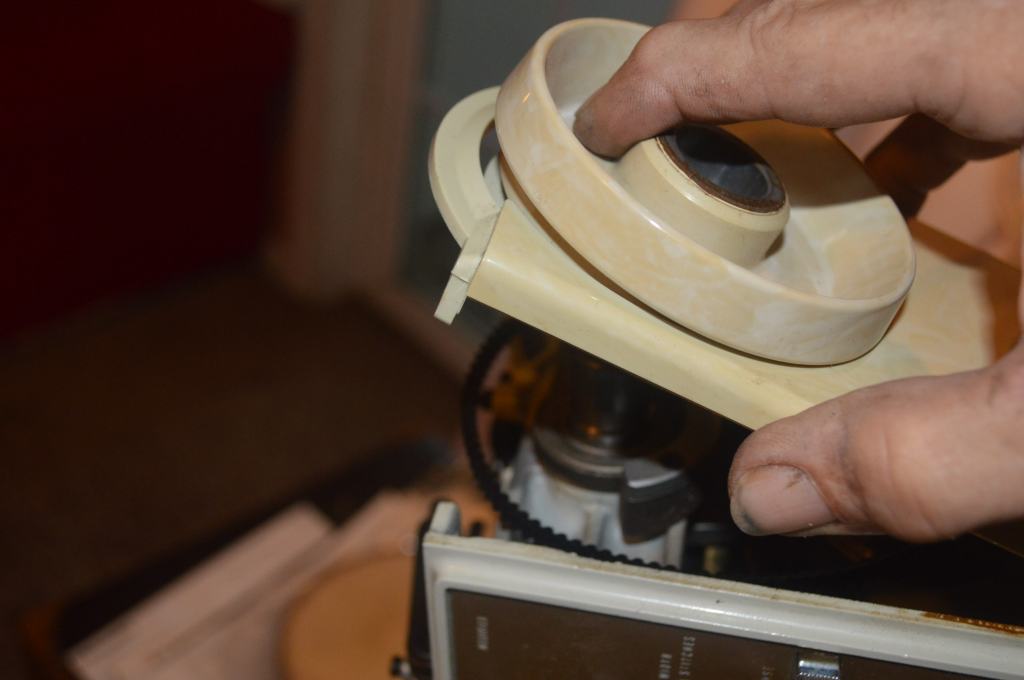

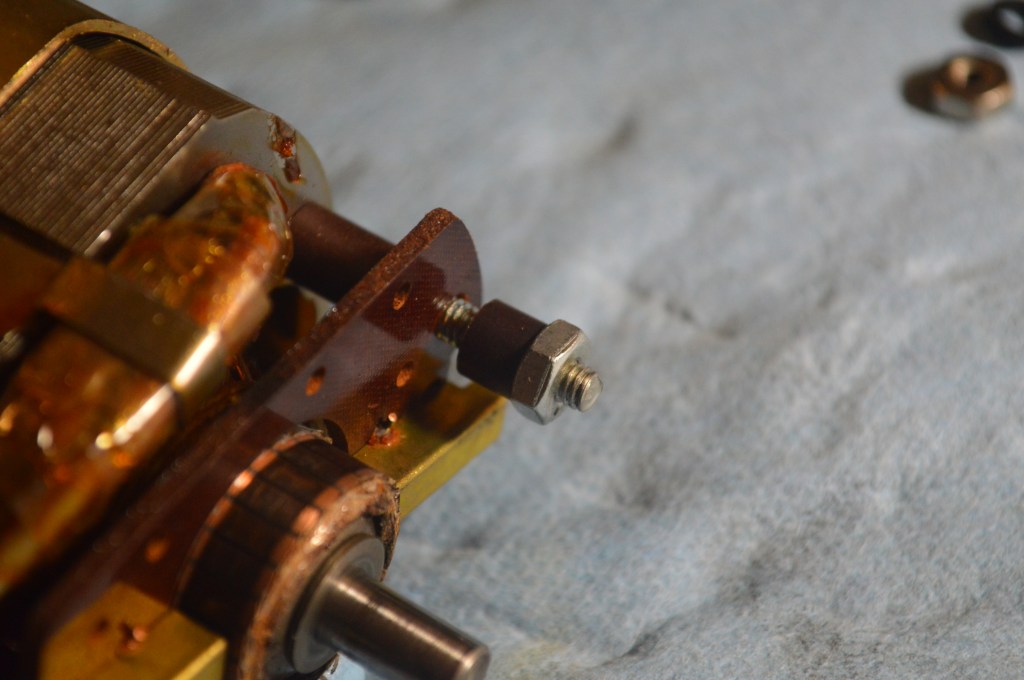

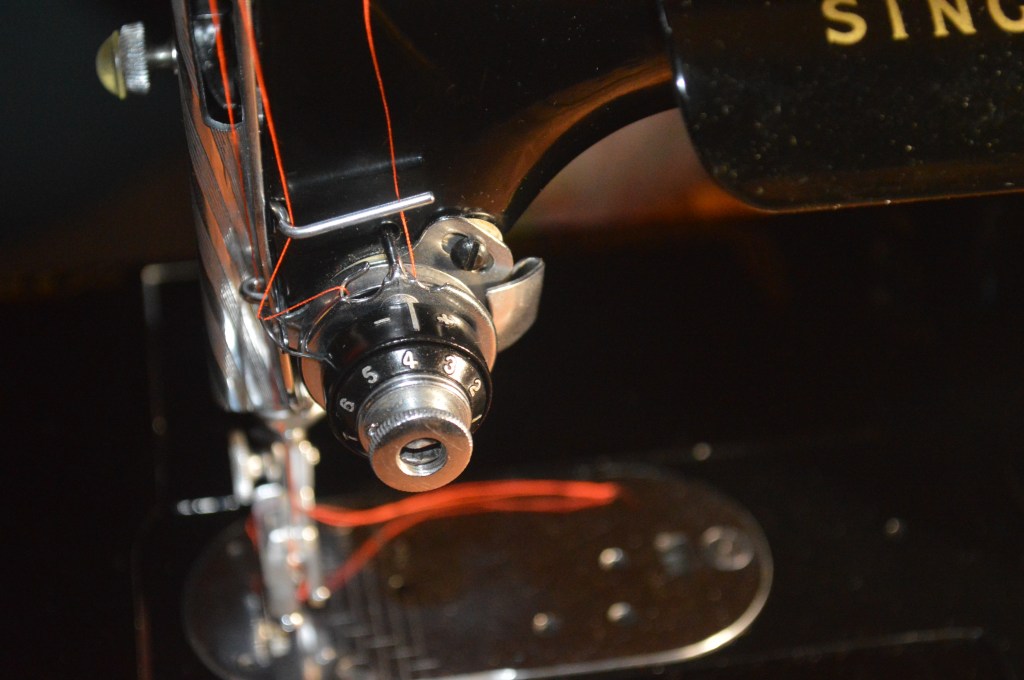

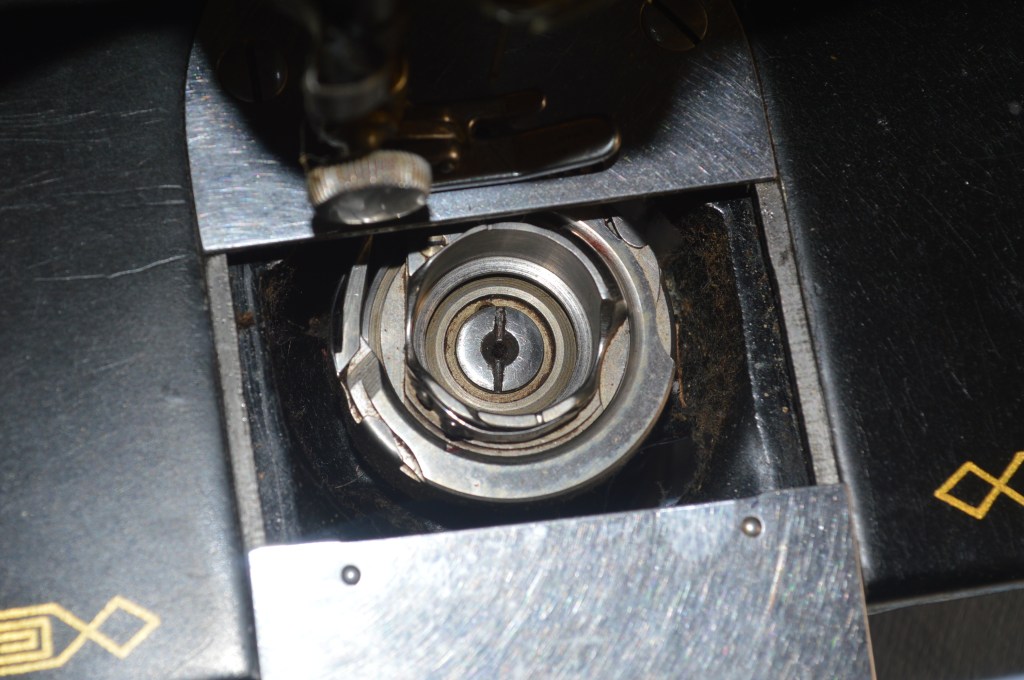

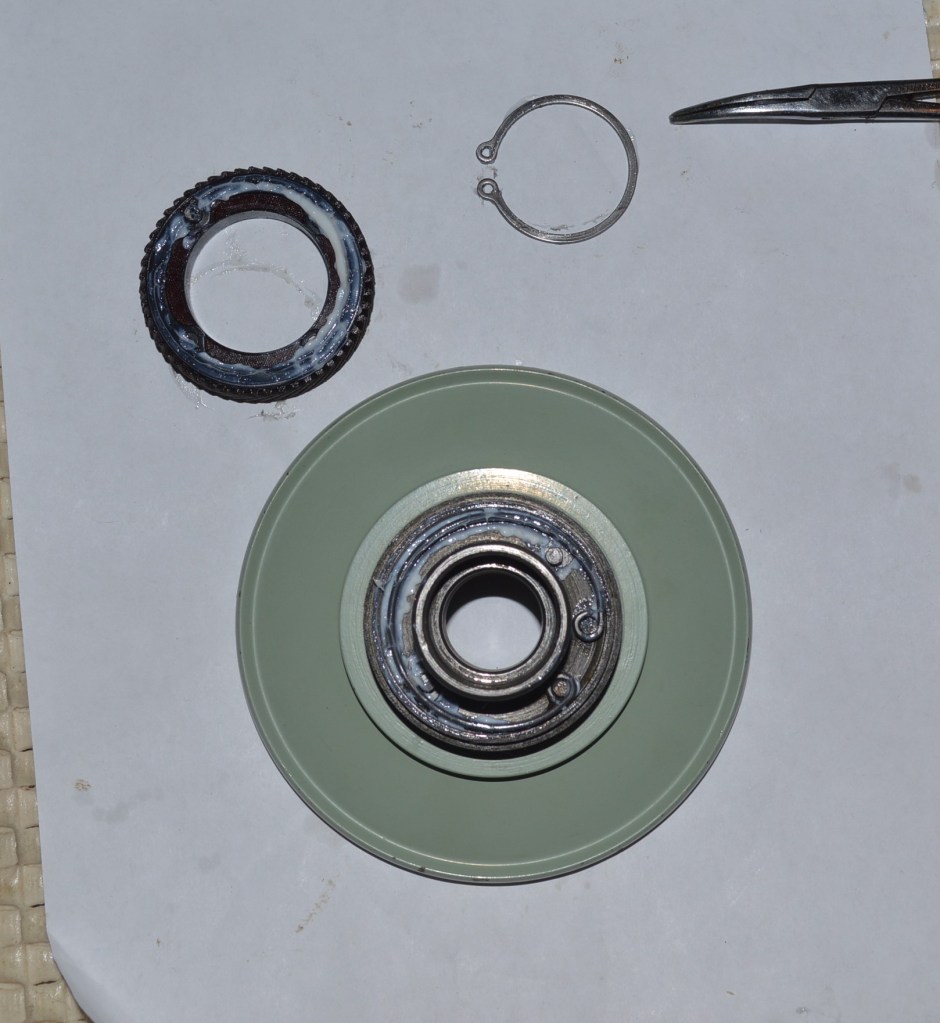

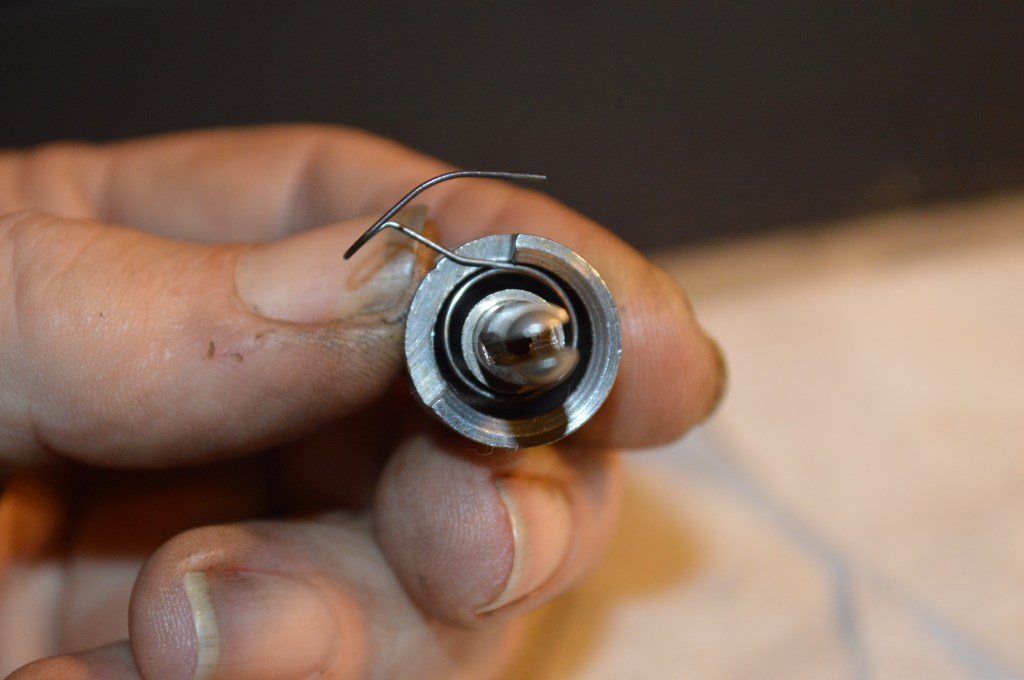

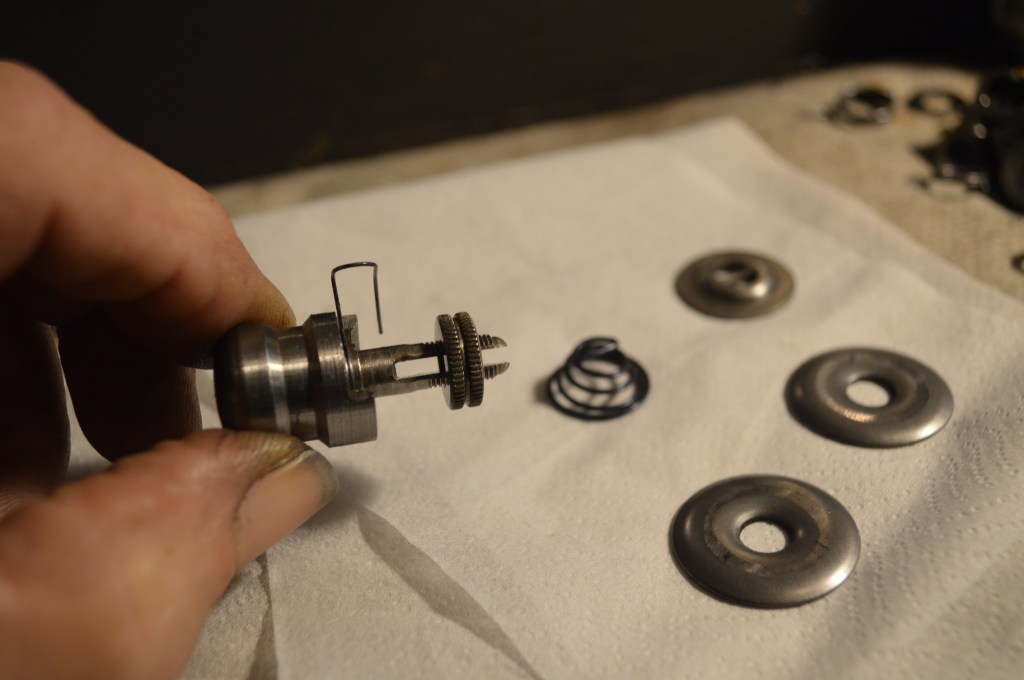

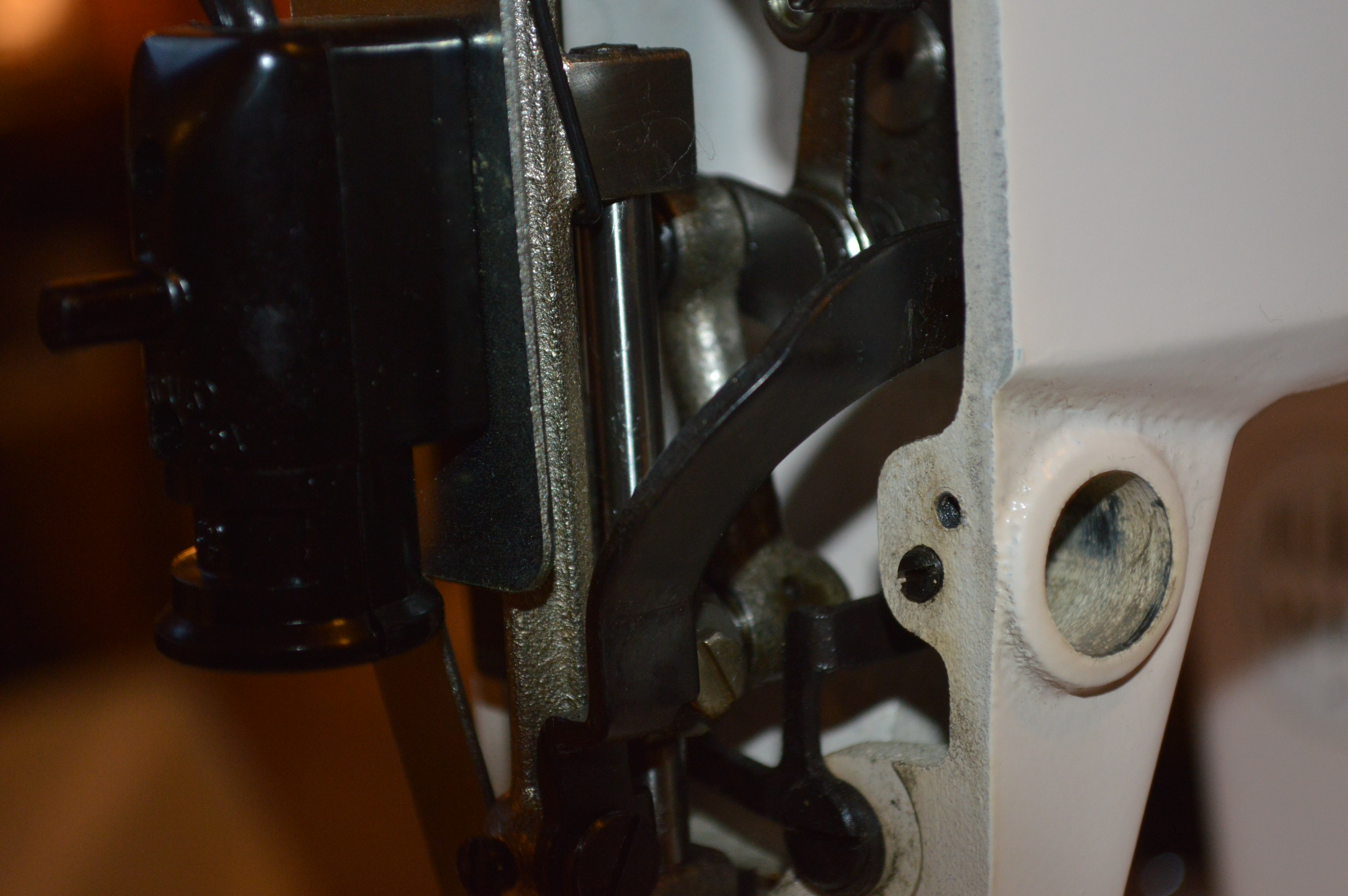

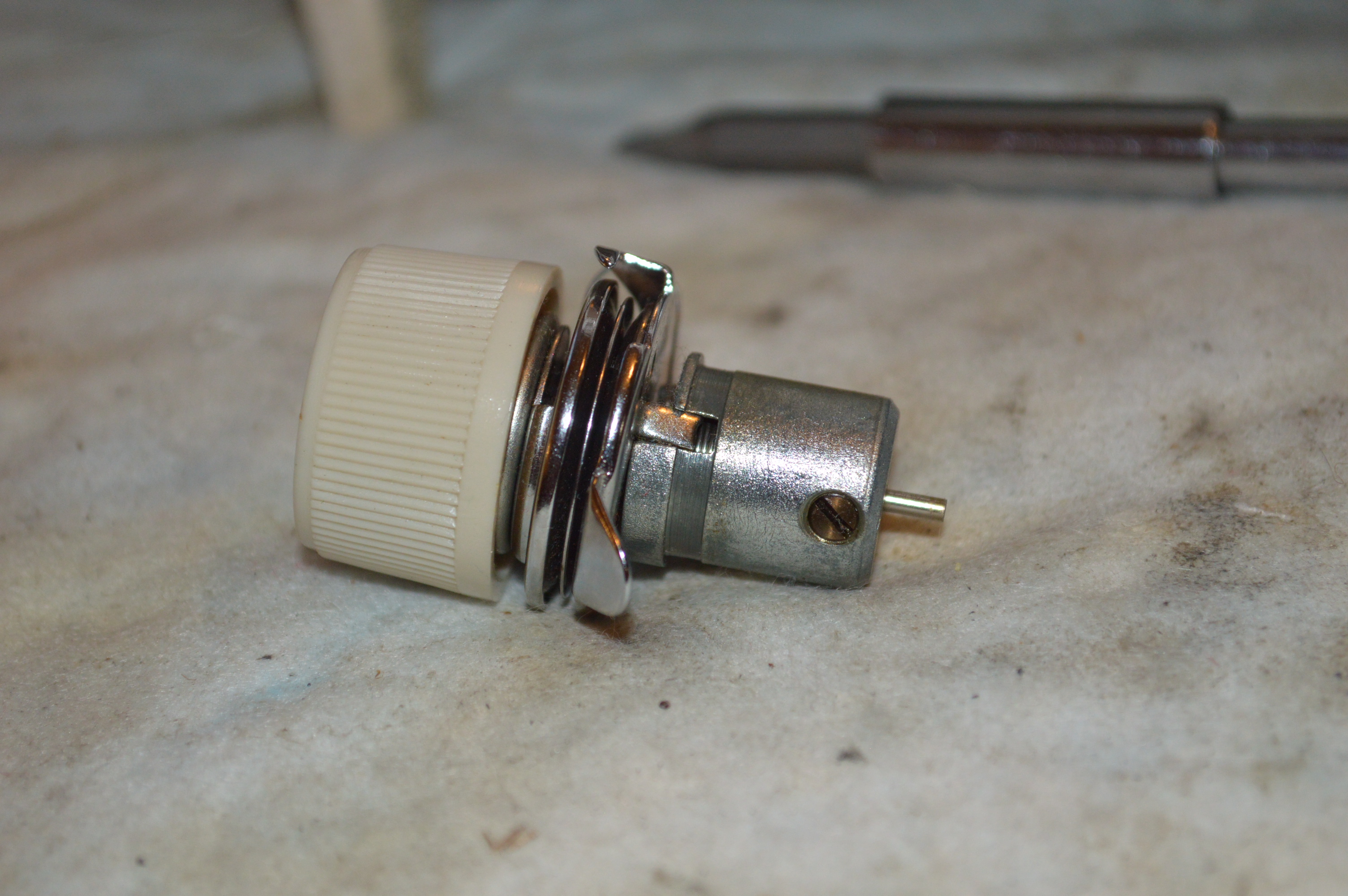

Next is the top tension control restoration. The tension discs and the tension disc shaft are polished. Everything else is cleaned. This will assure a smooth thread path and even thread tension.

The large plated pieces are cleaned and then polished. Taking pictures of polished pieces isn’t easy, so you will see them shine on the assembled machine! Sorry, but it is worth the wait… The same goes for the little pieces like the stitch length lever, bobbin winder guide, and other little bits and pieces.

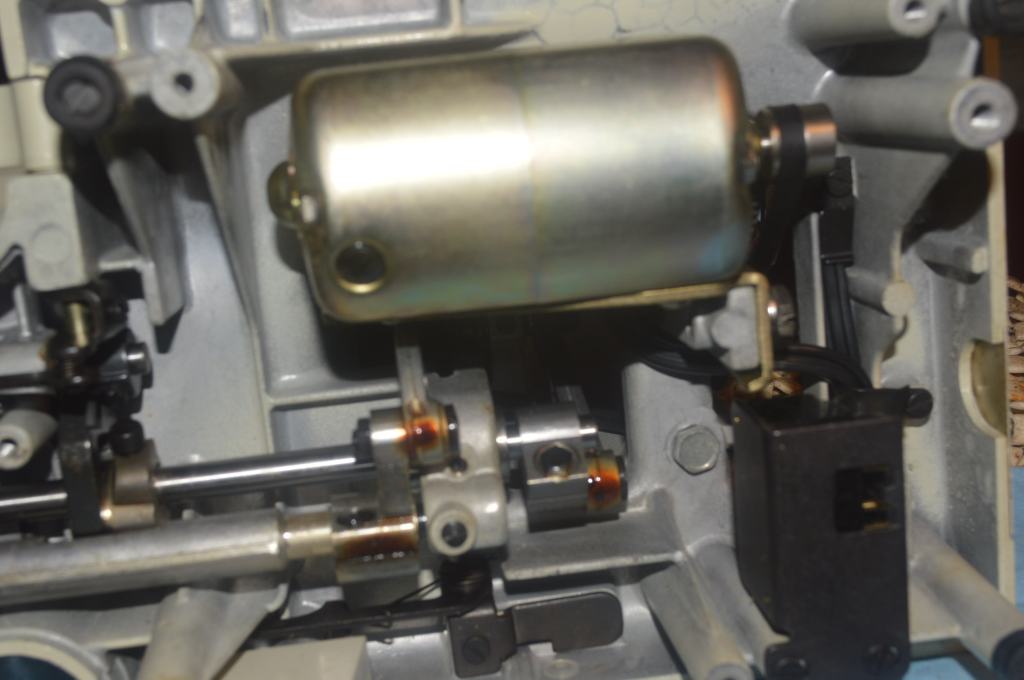

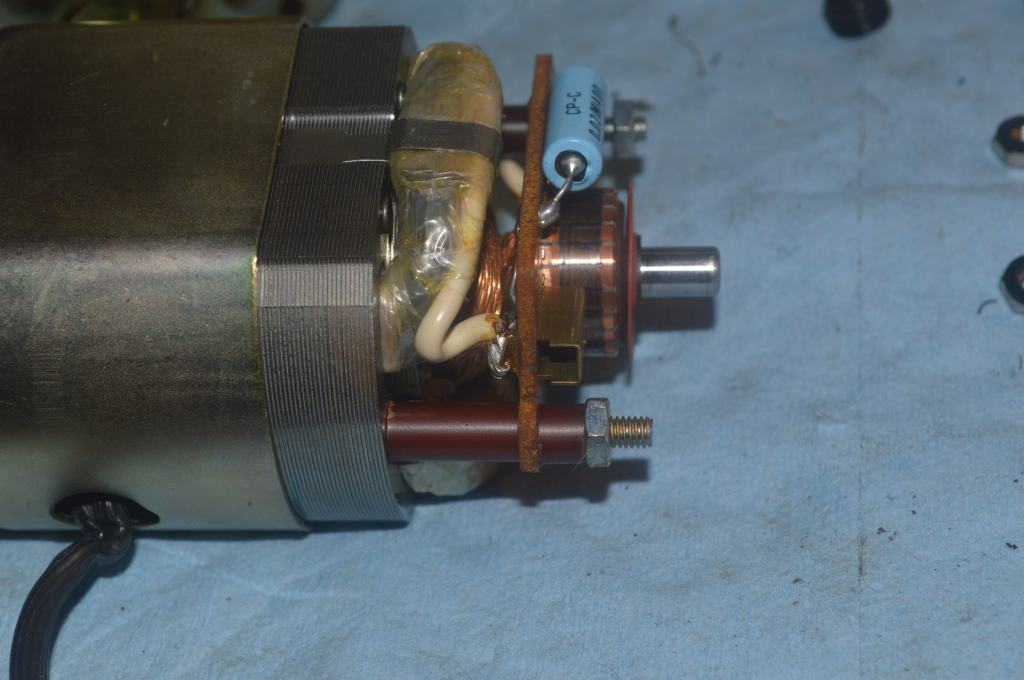

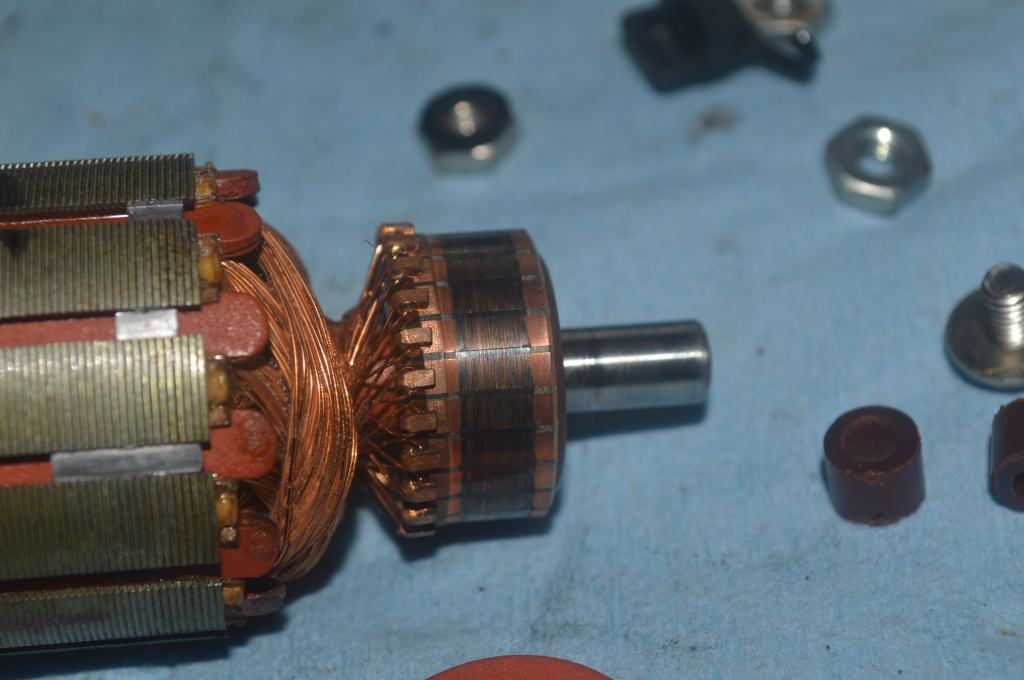

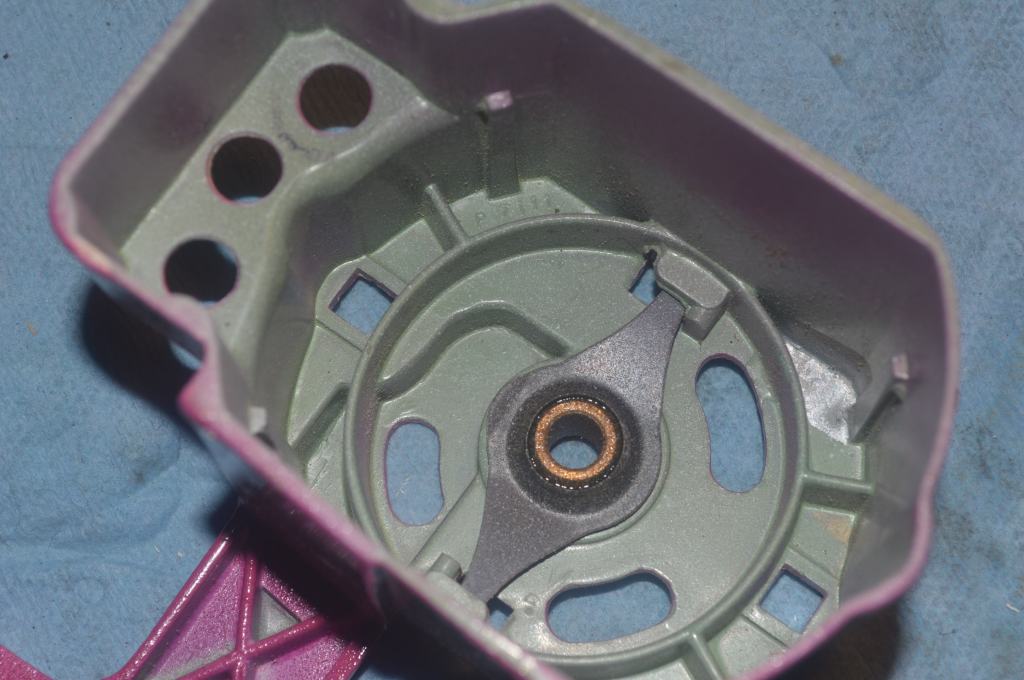

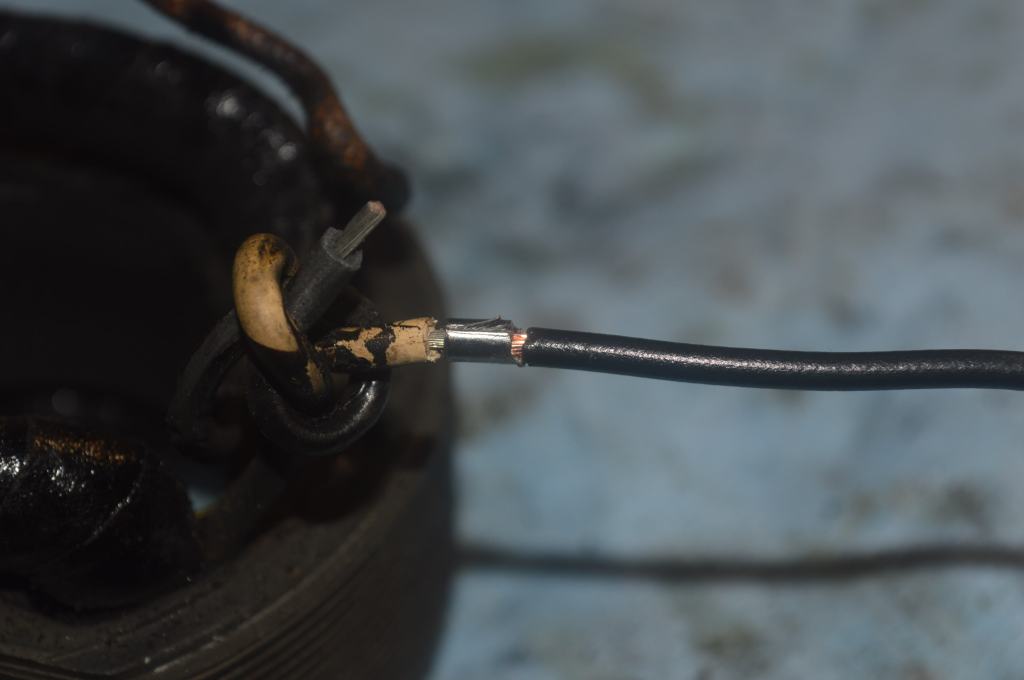

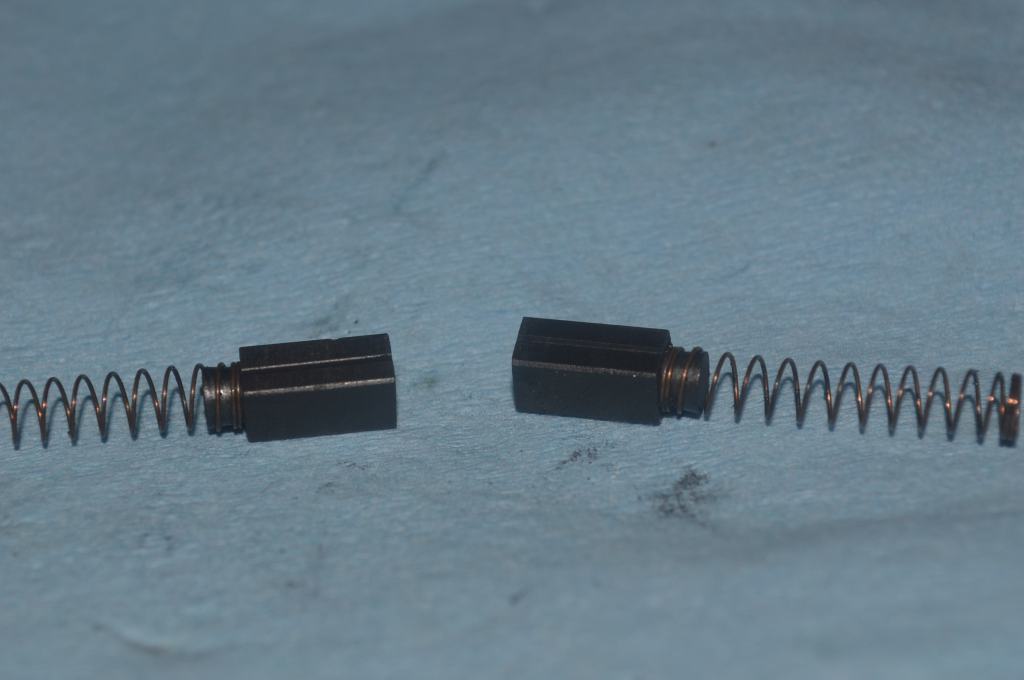

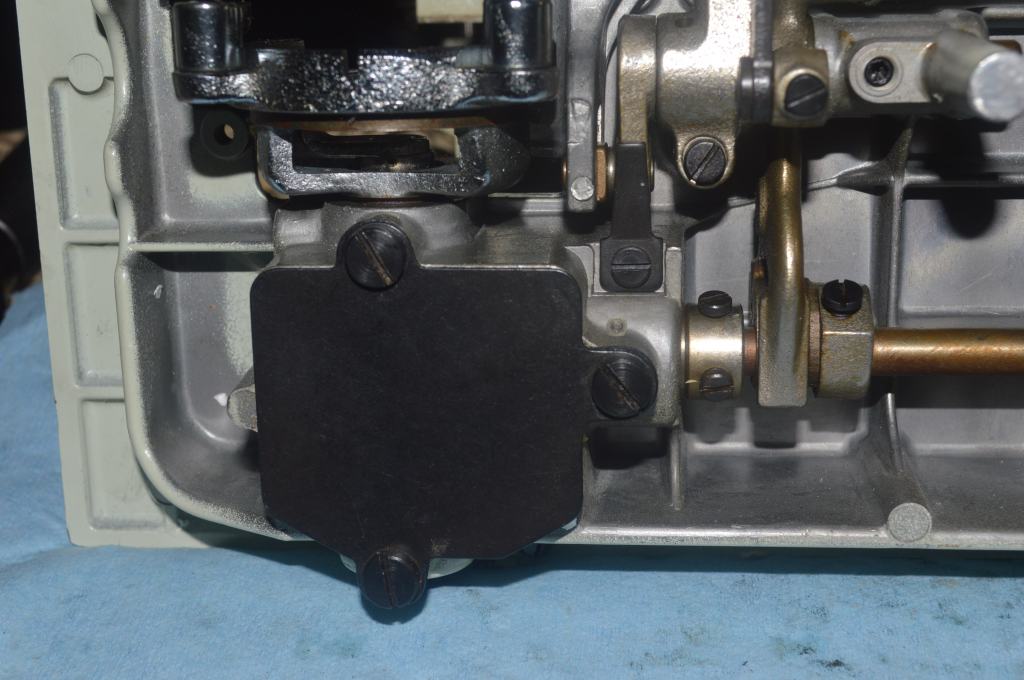

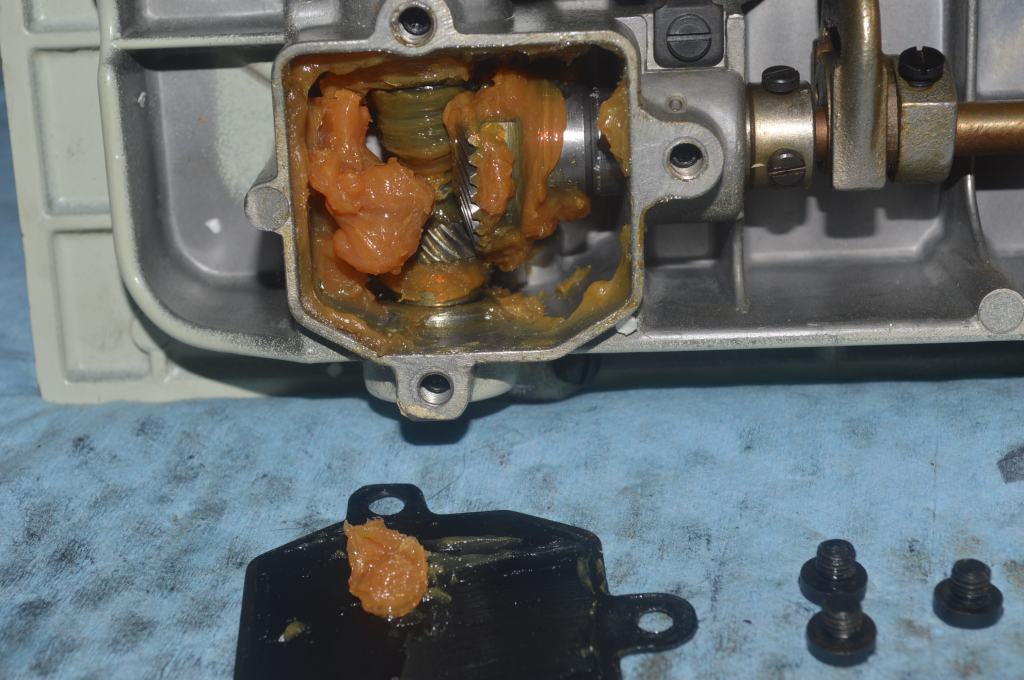

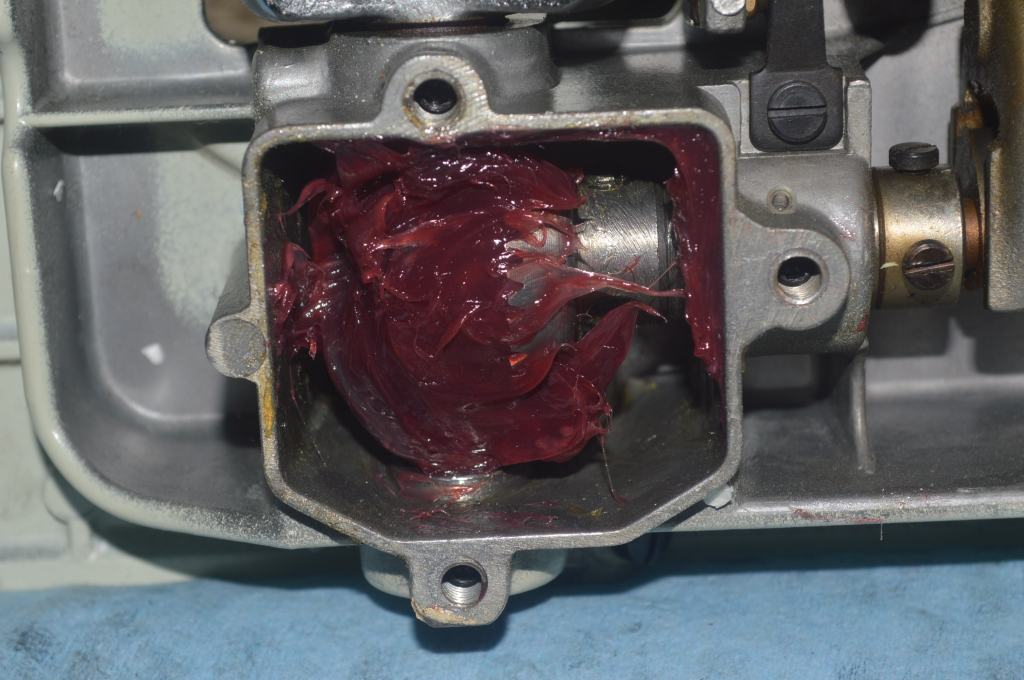

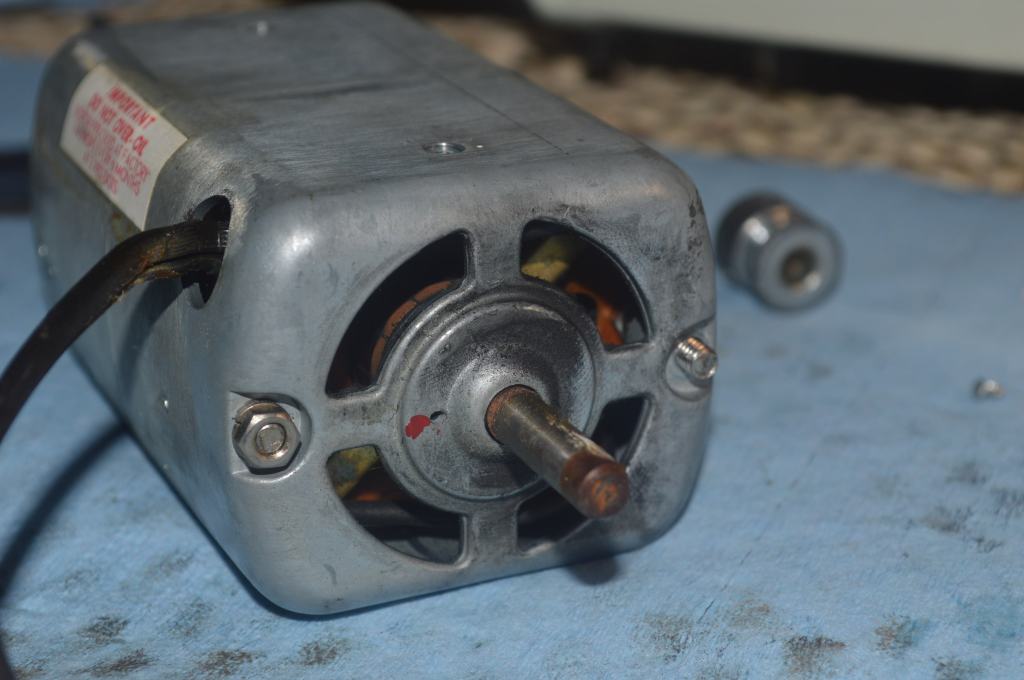

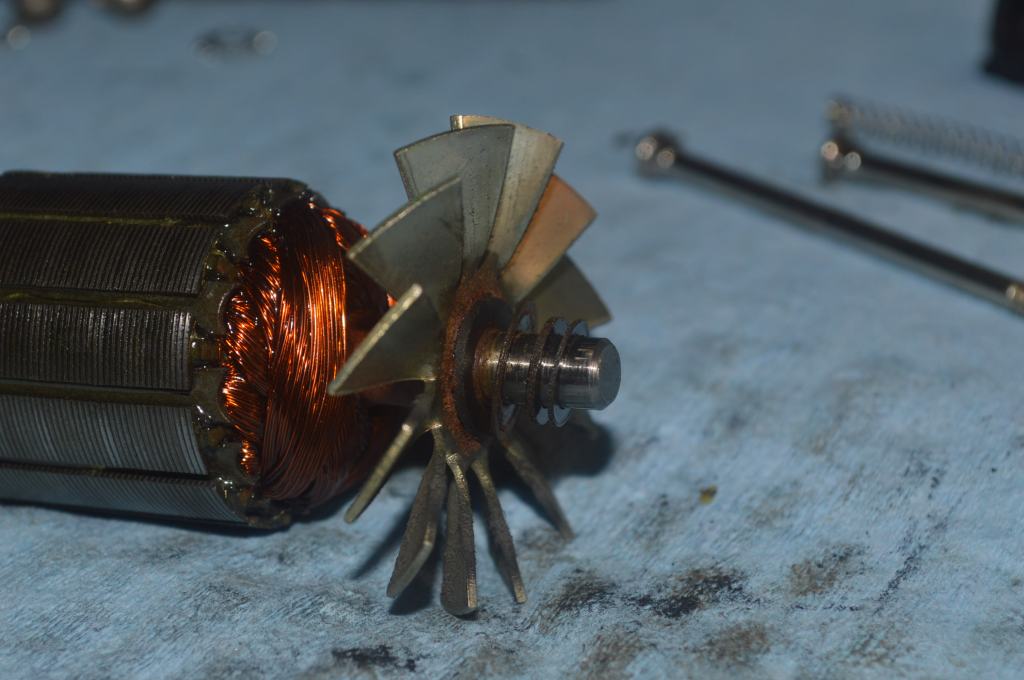

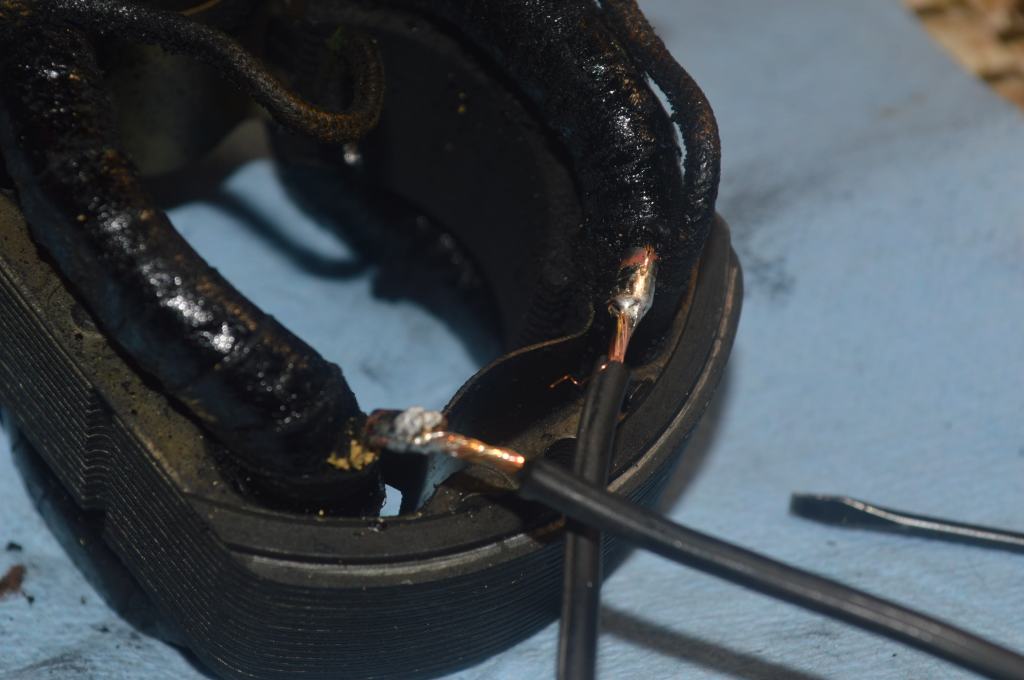

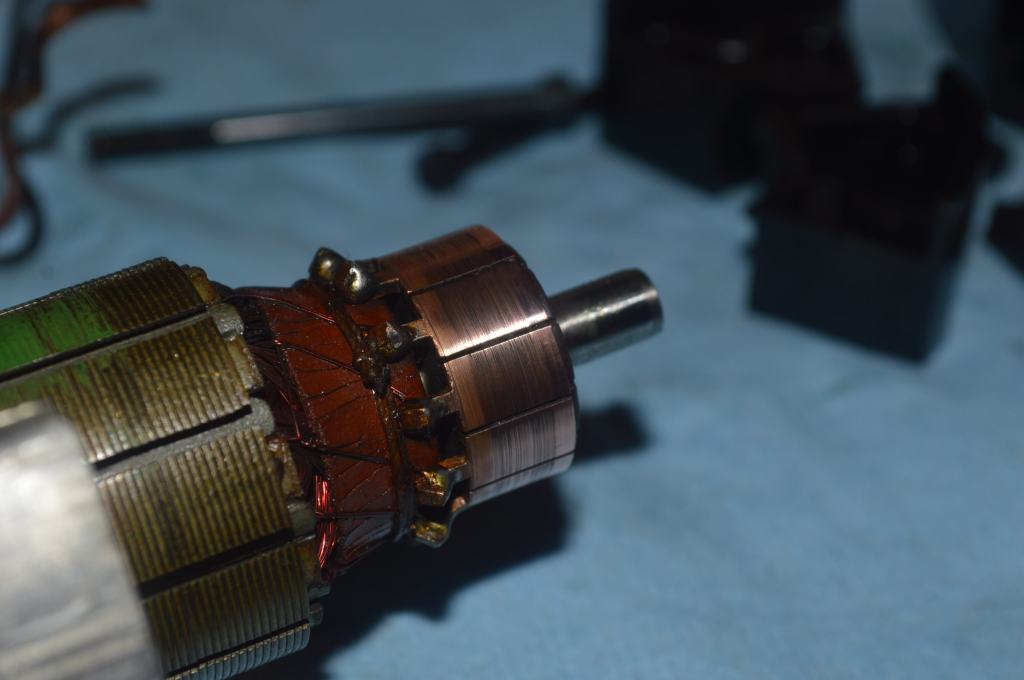

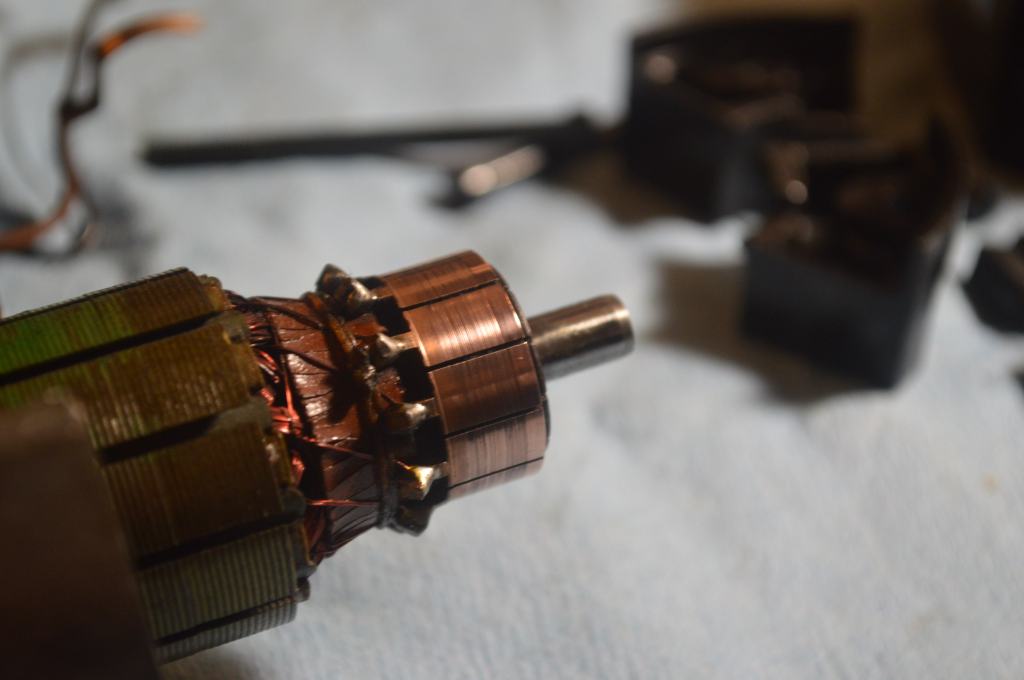

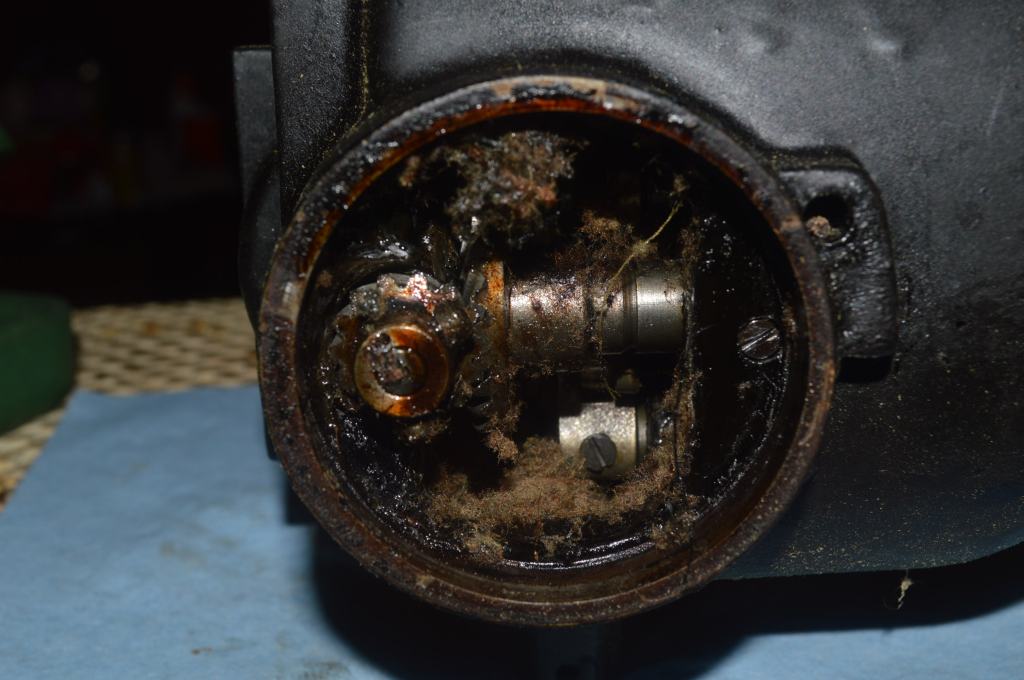

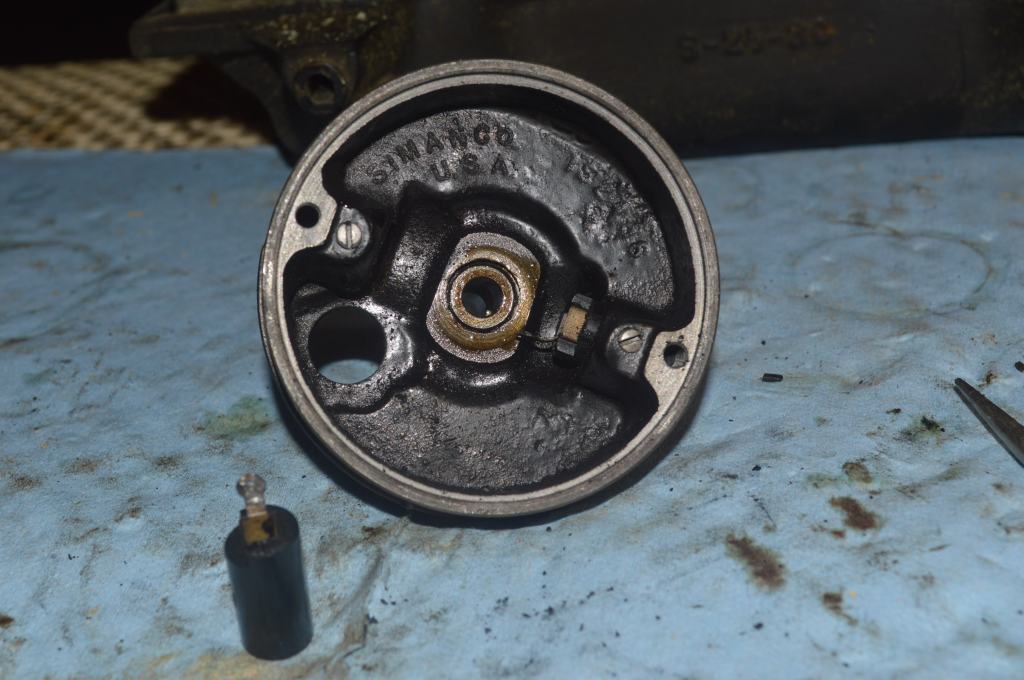

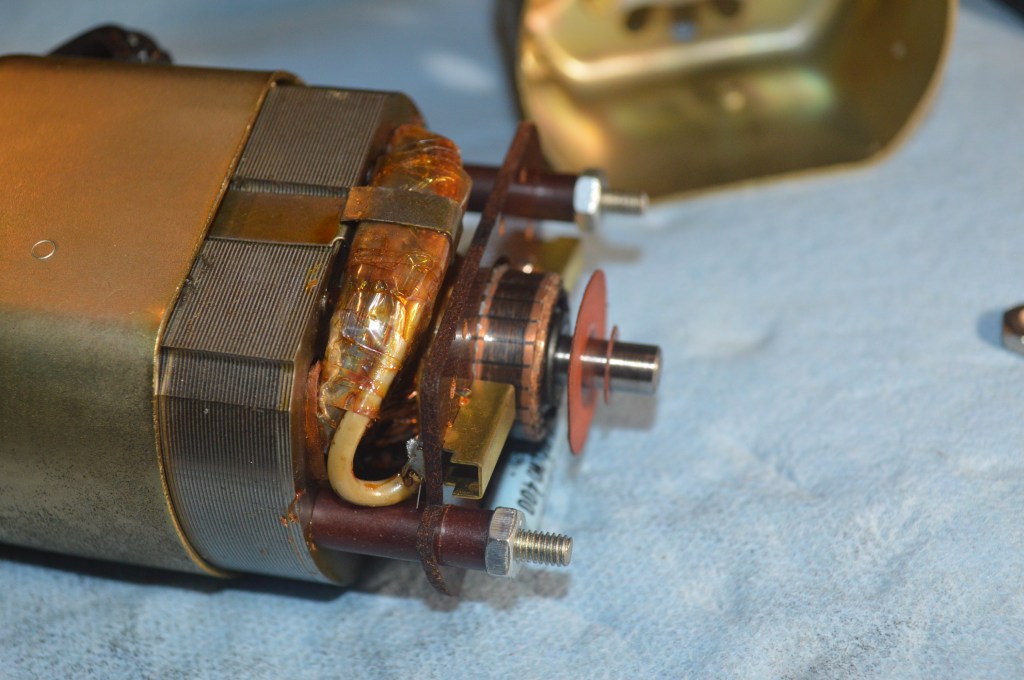

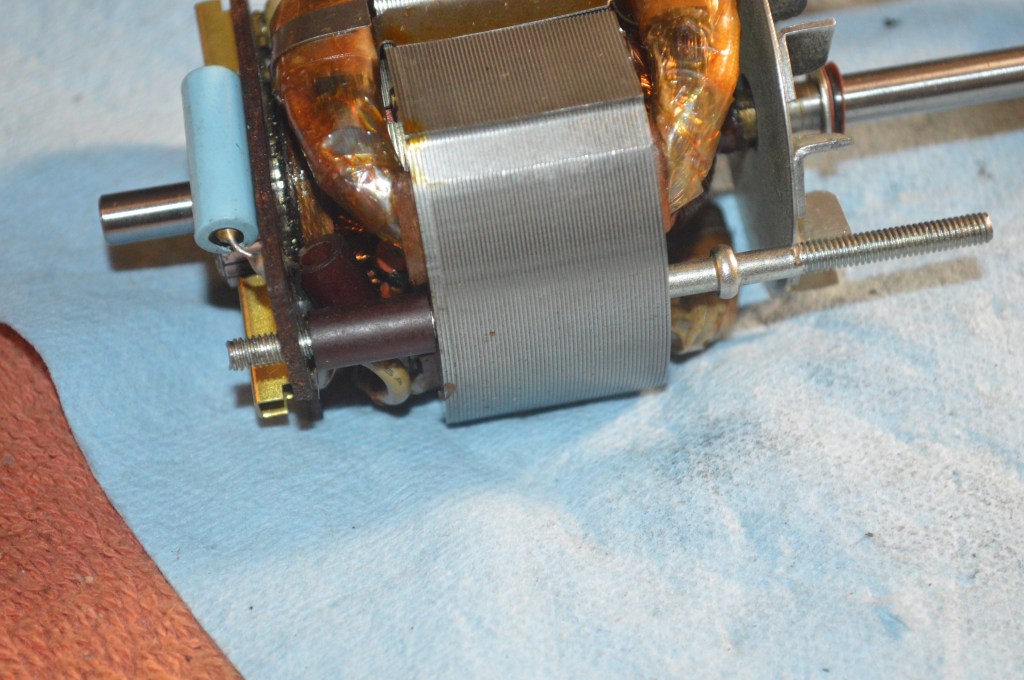

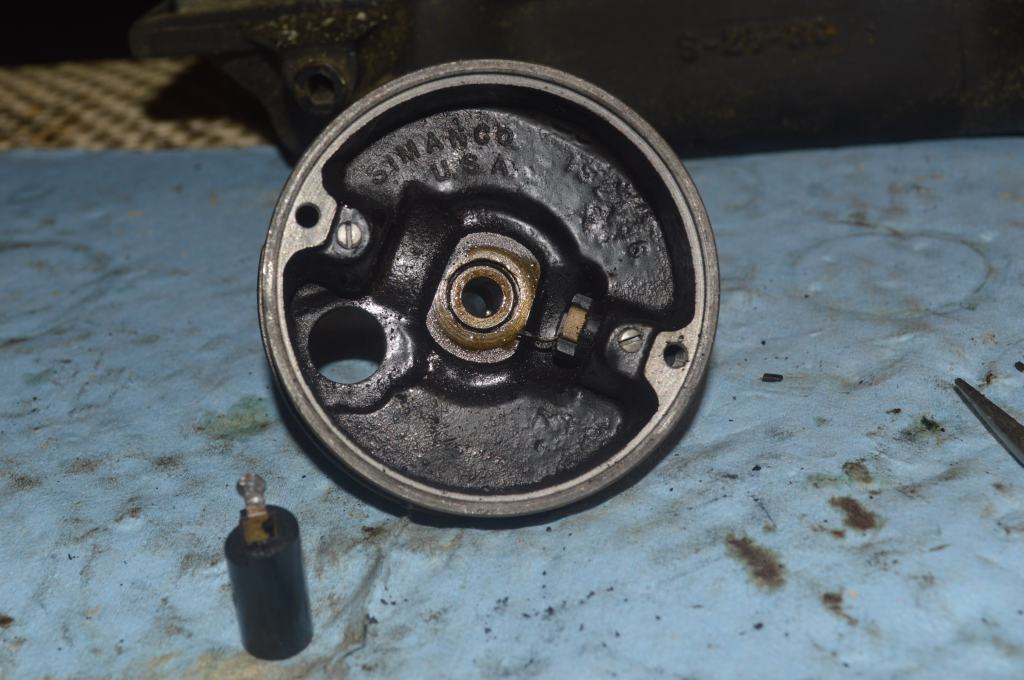

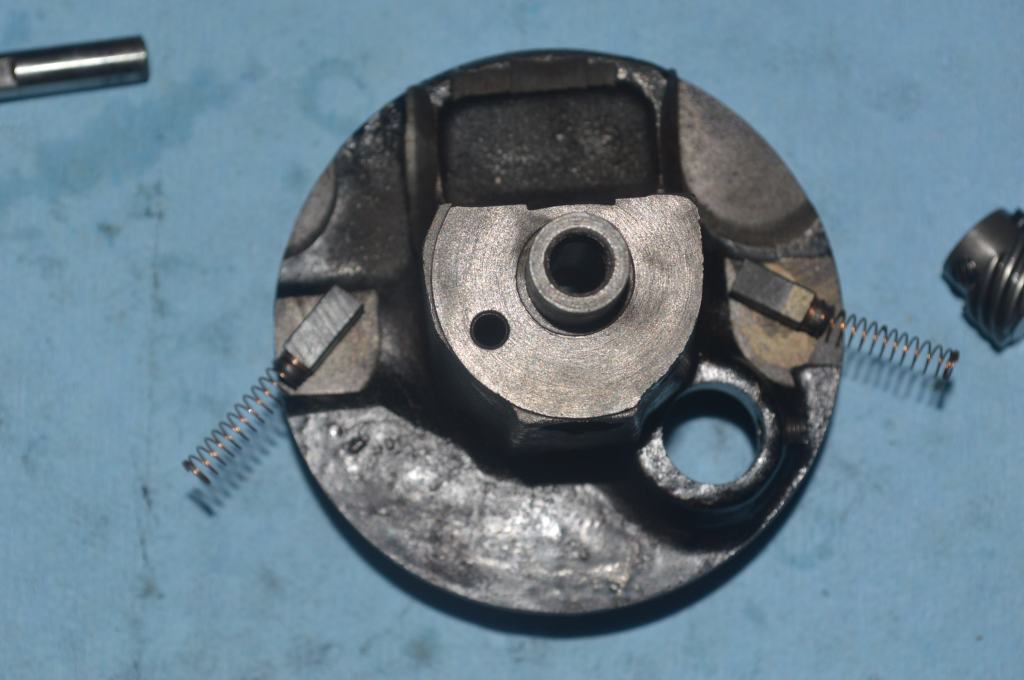

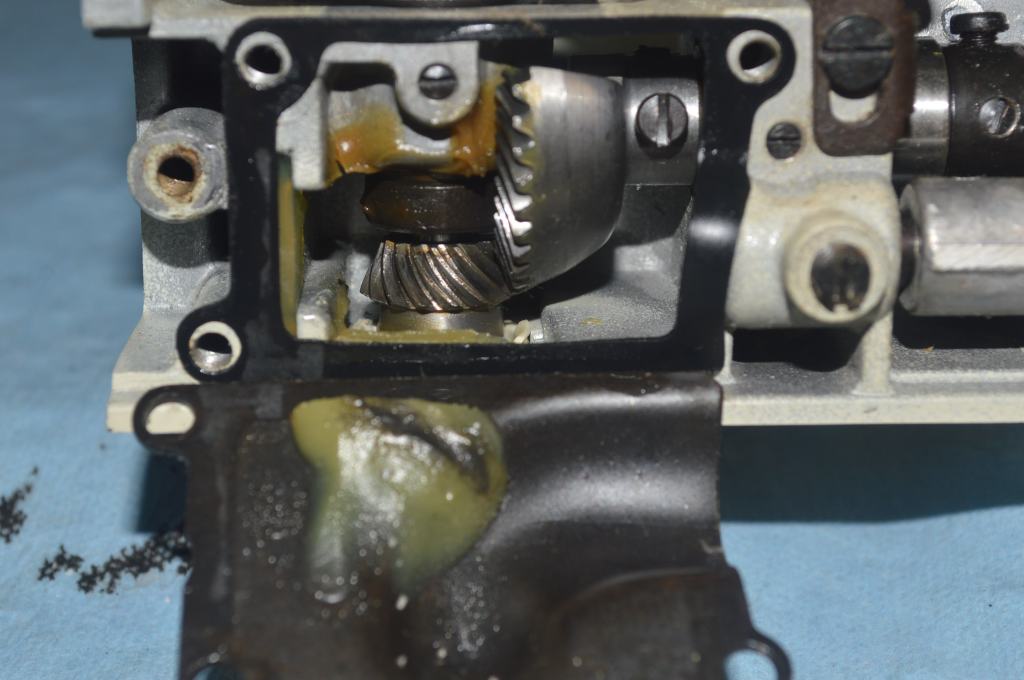

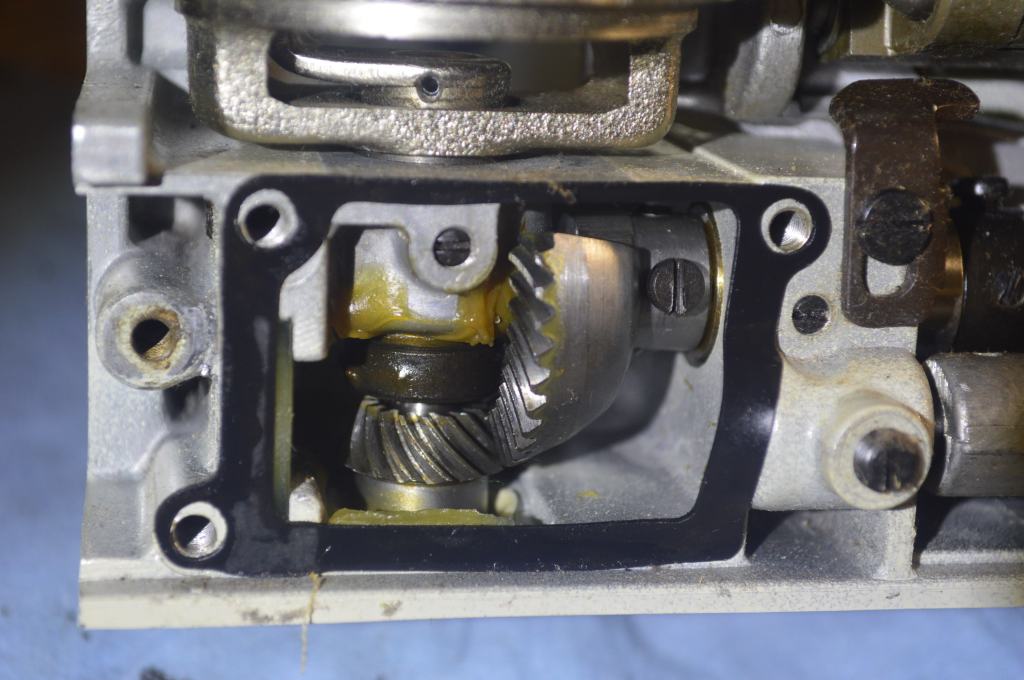

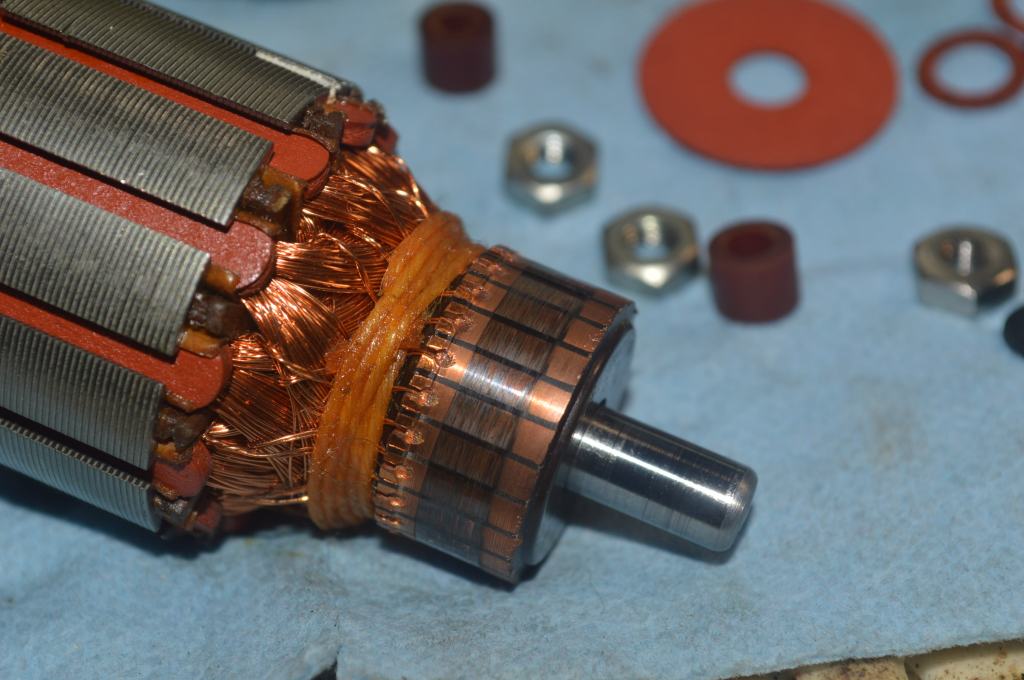

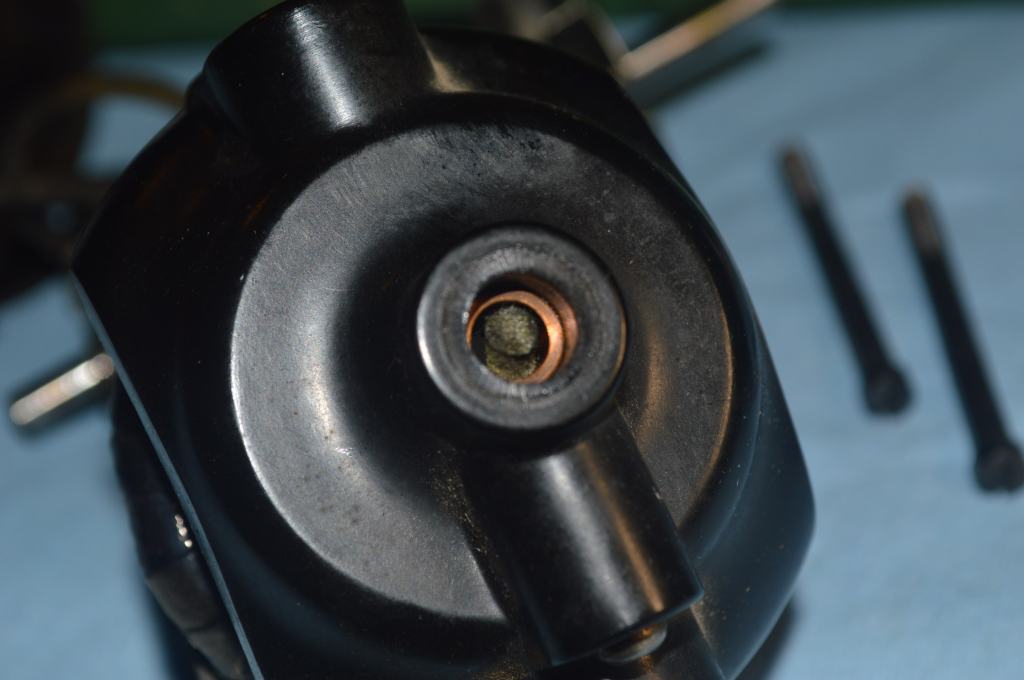

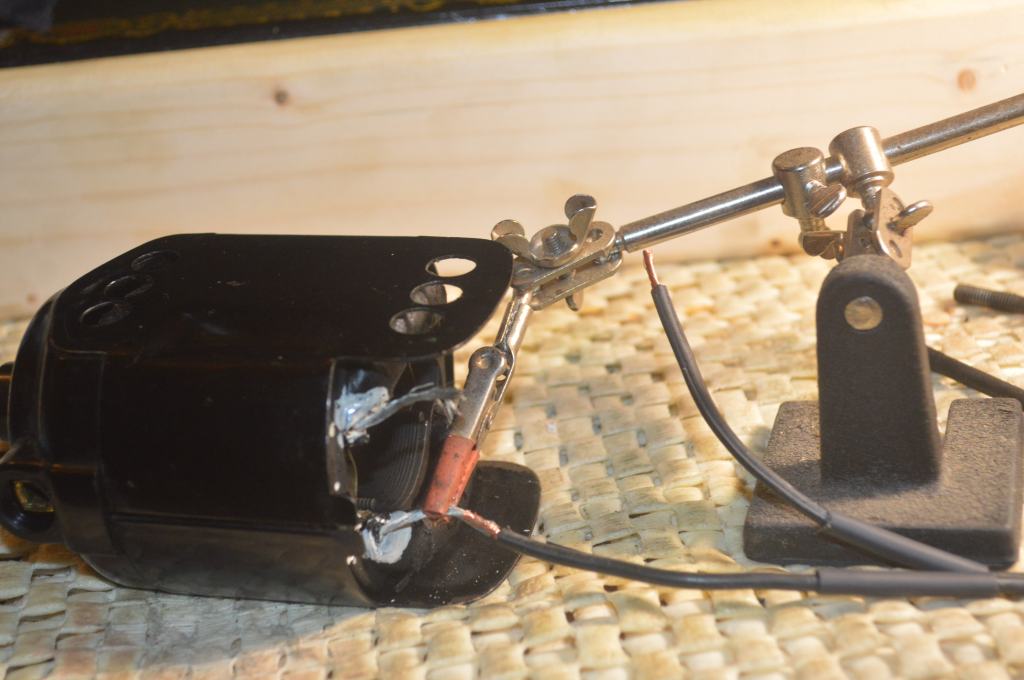

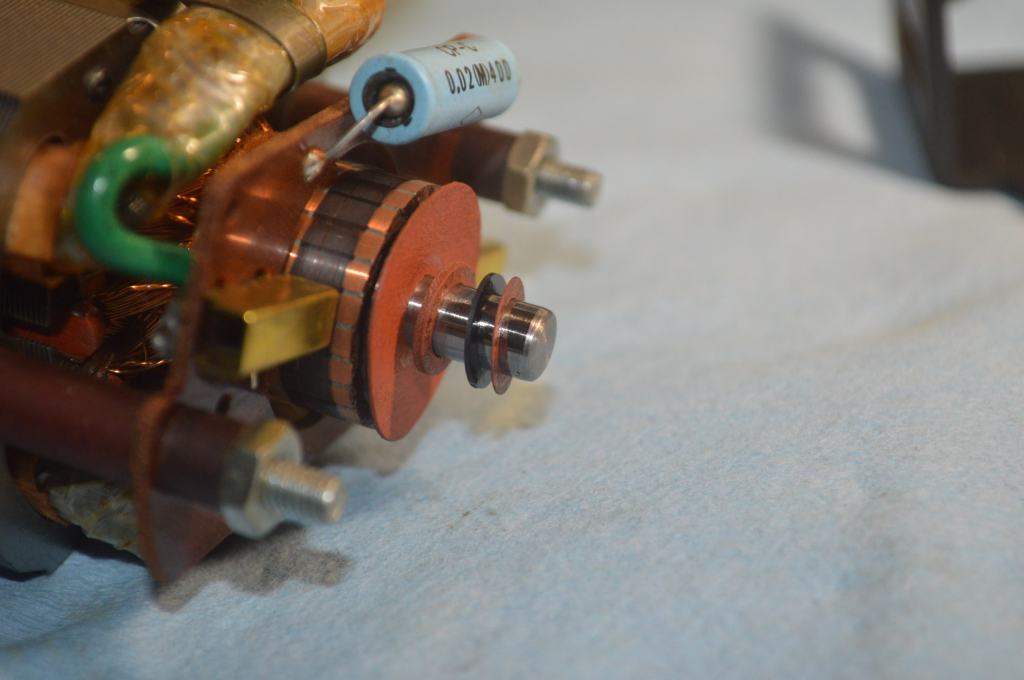

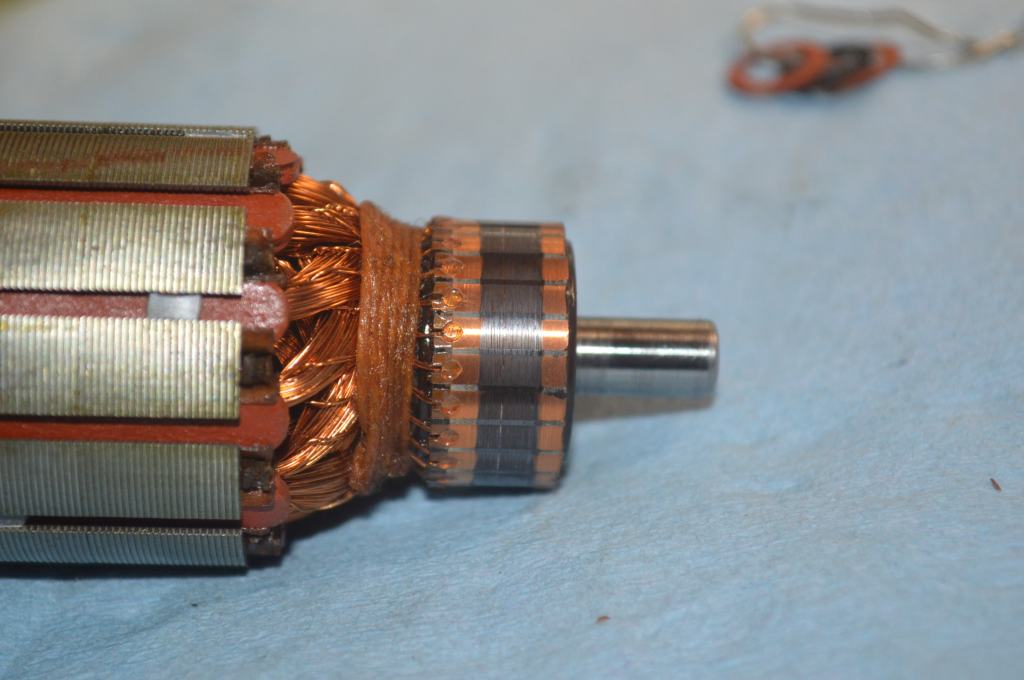

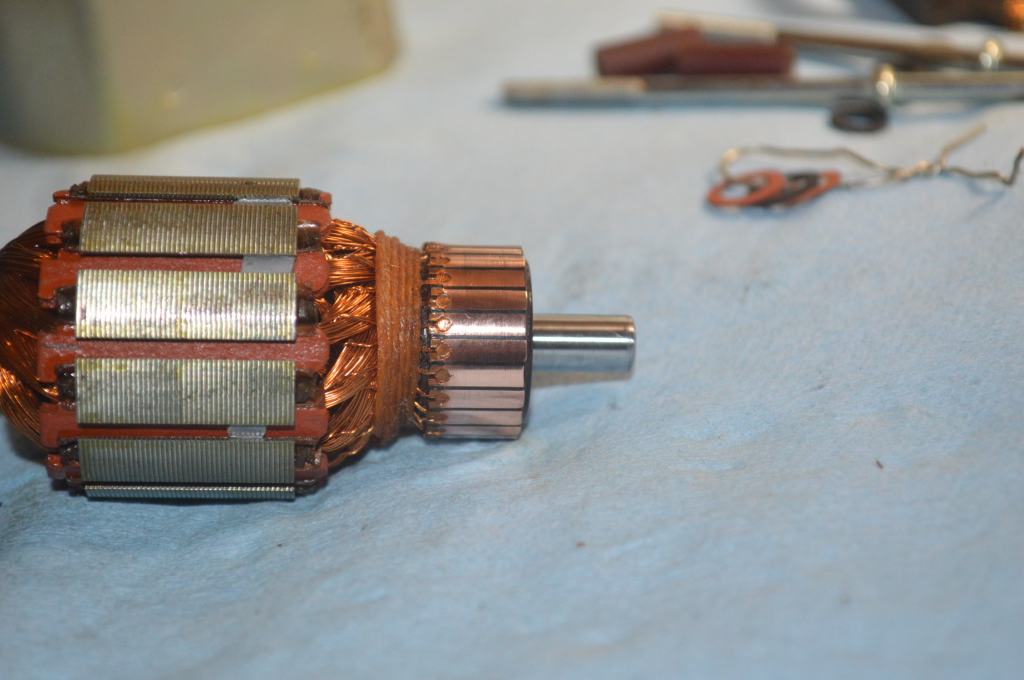

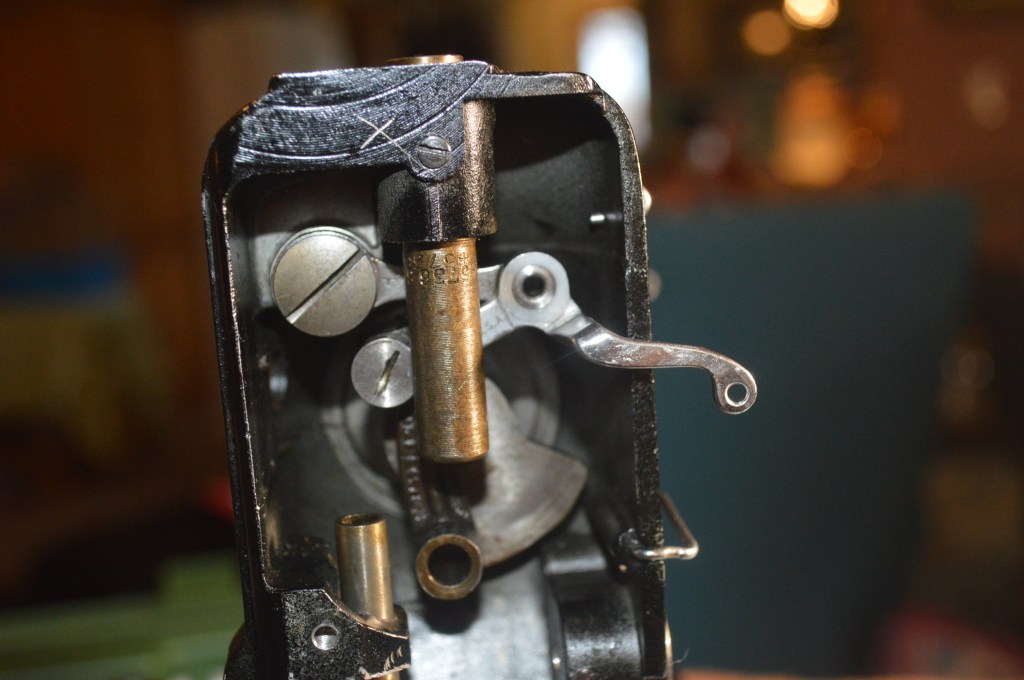

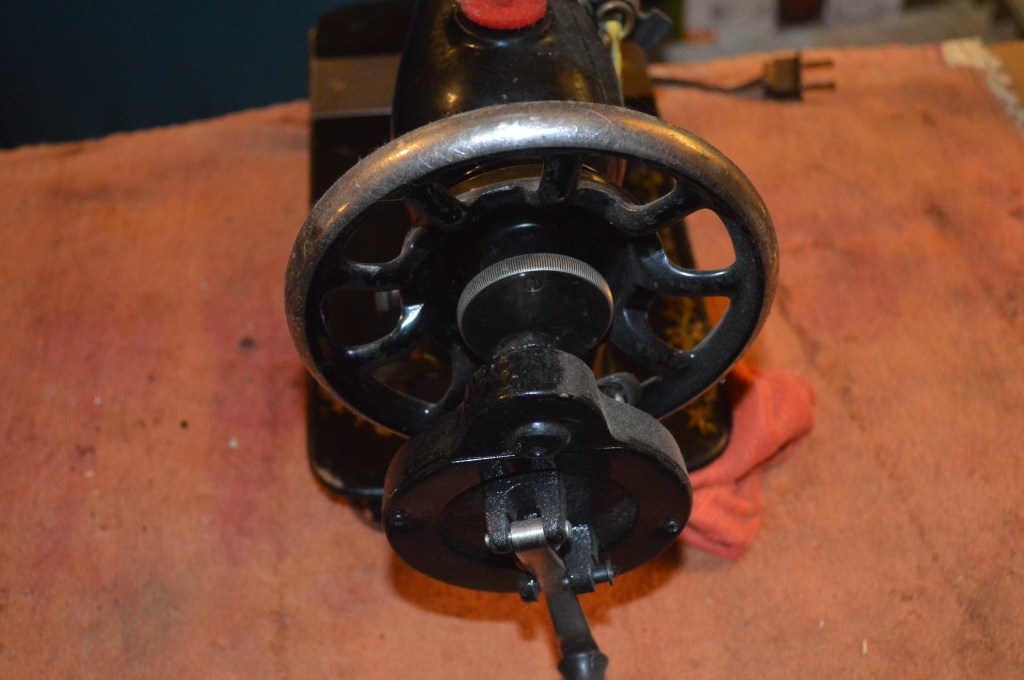

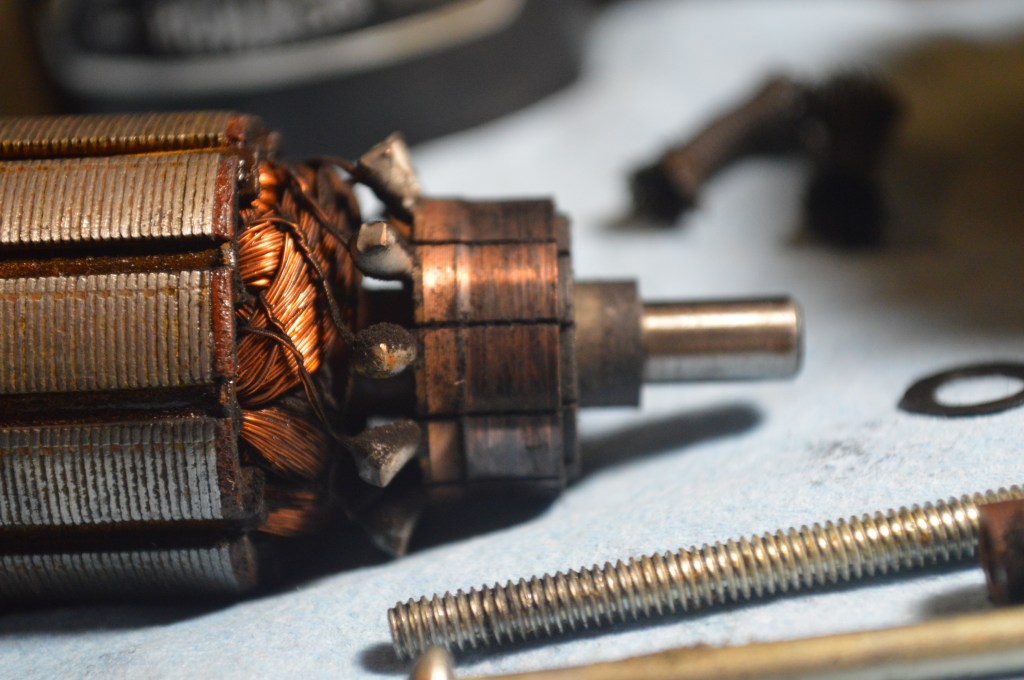

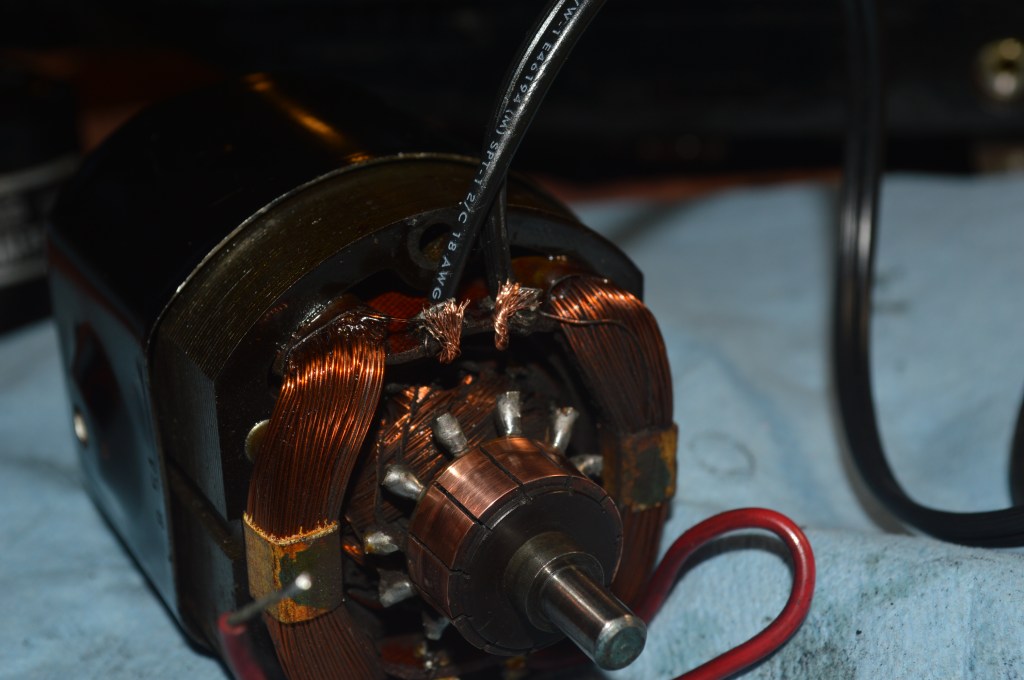

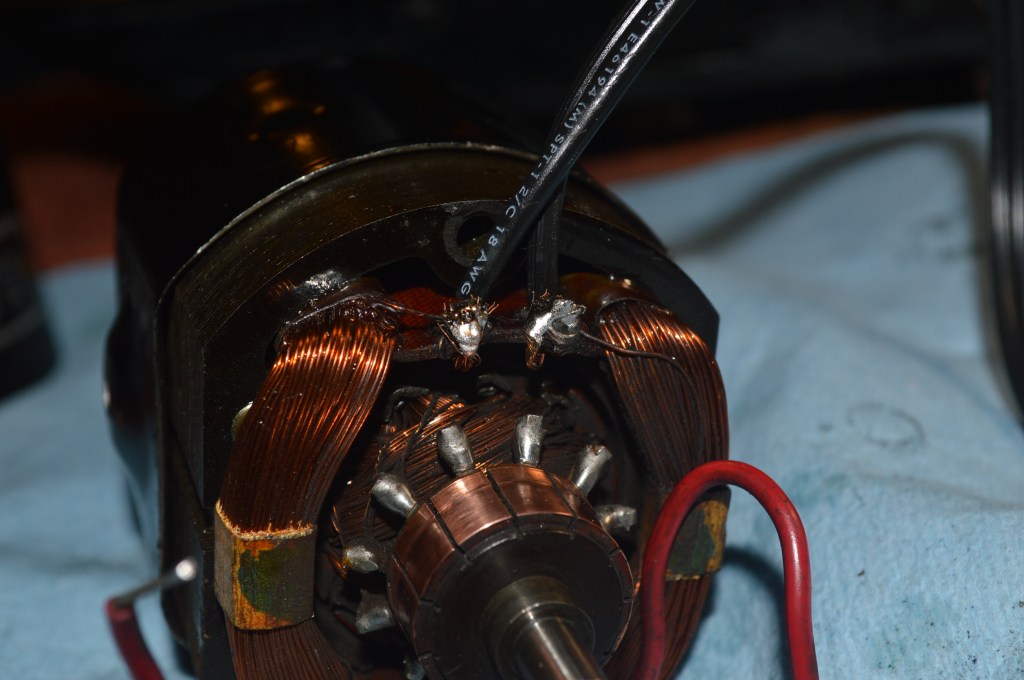

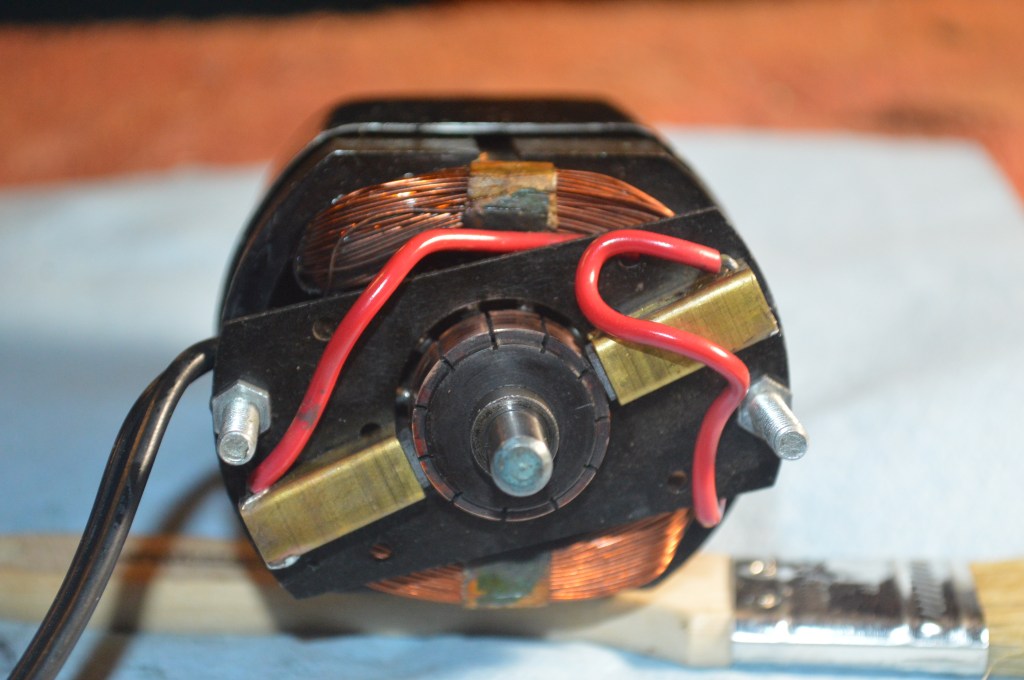

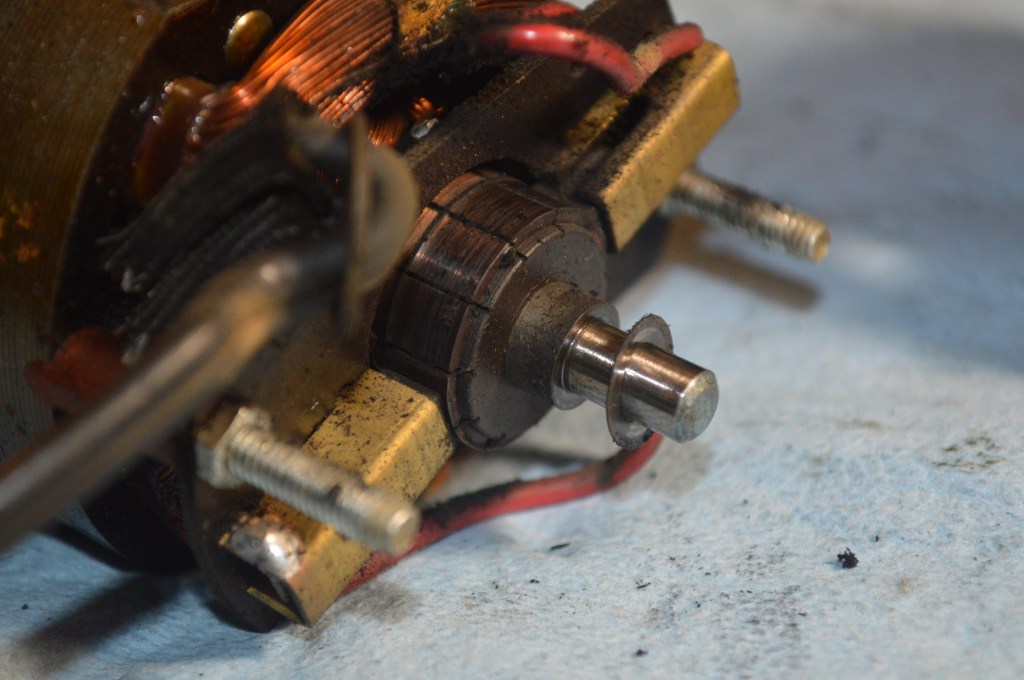

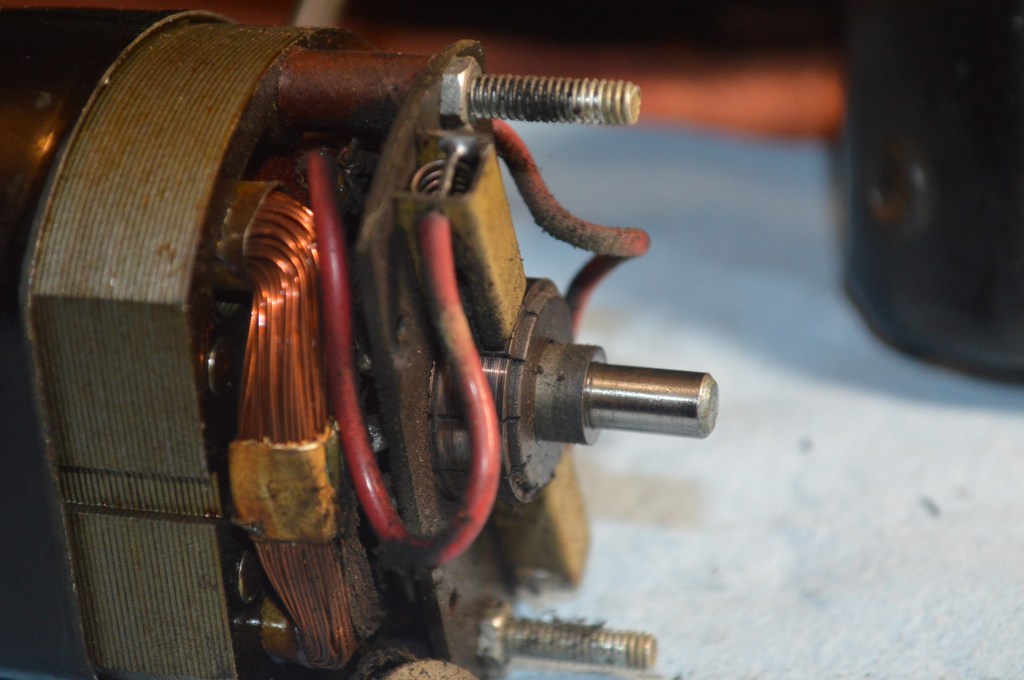

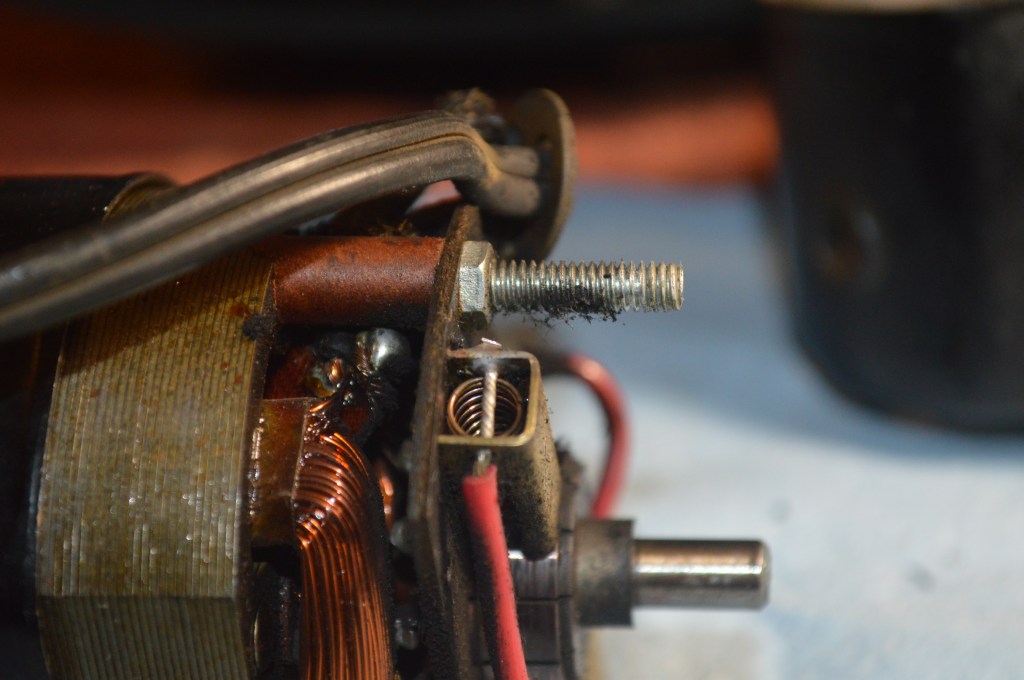

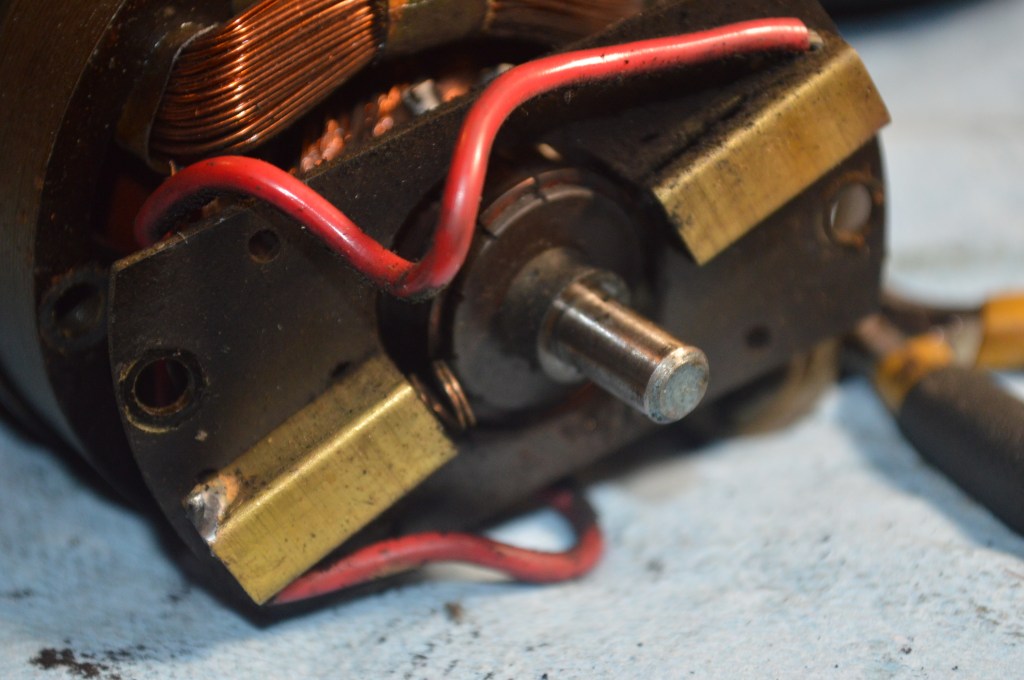

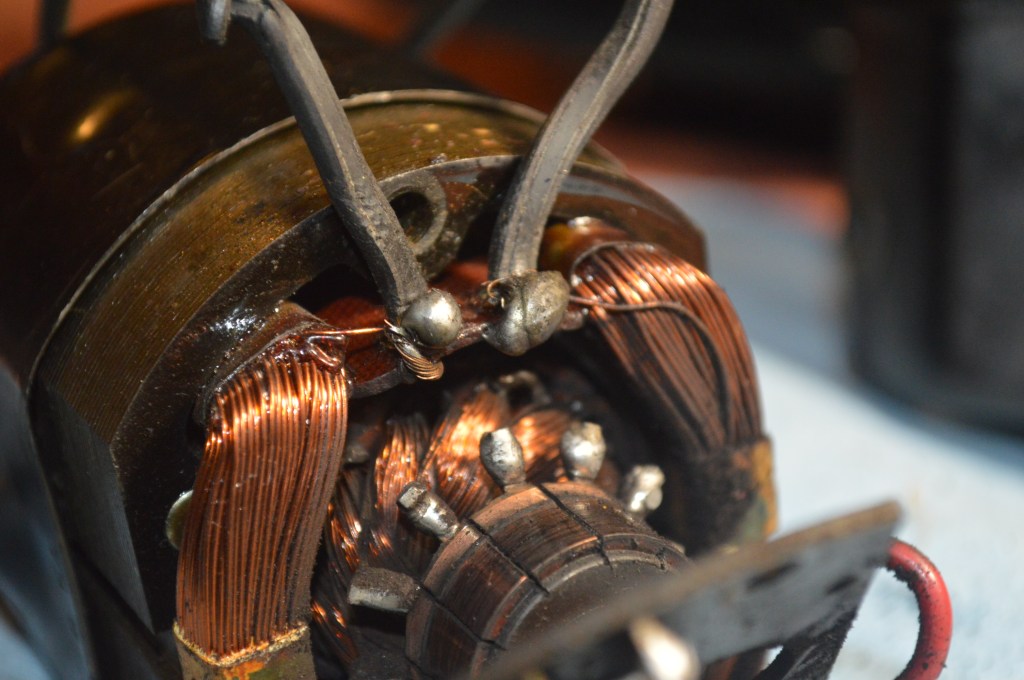

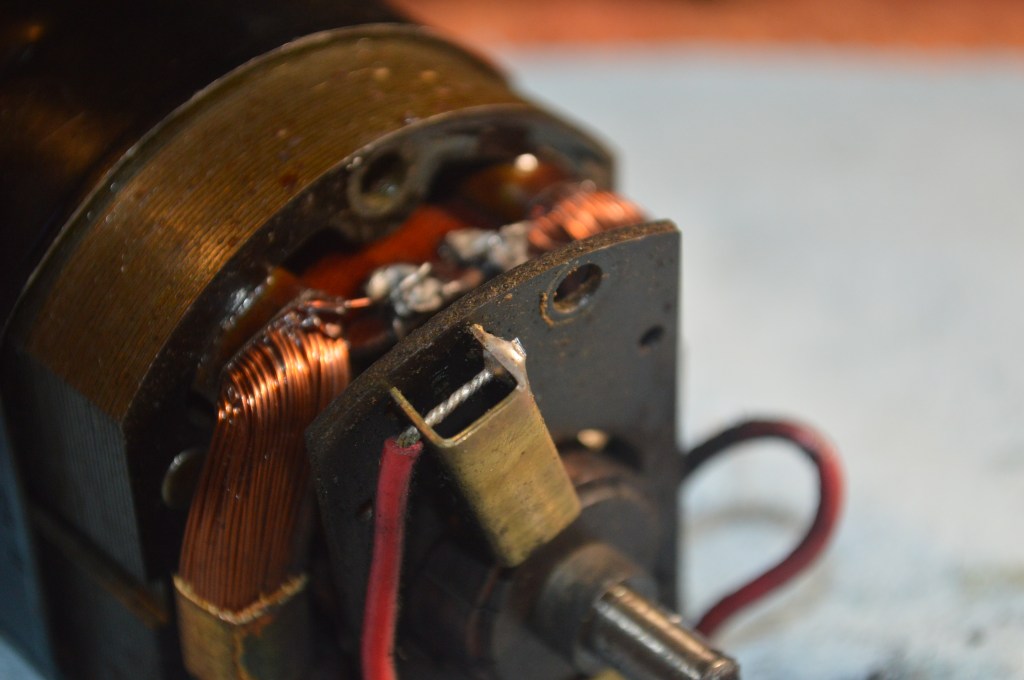

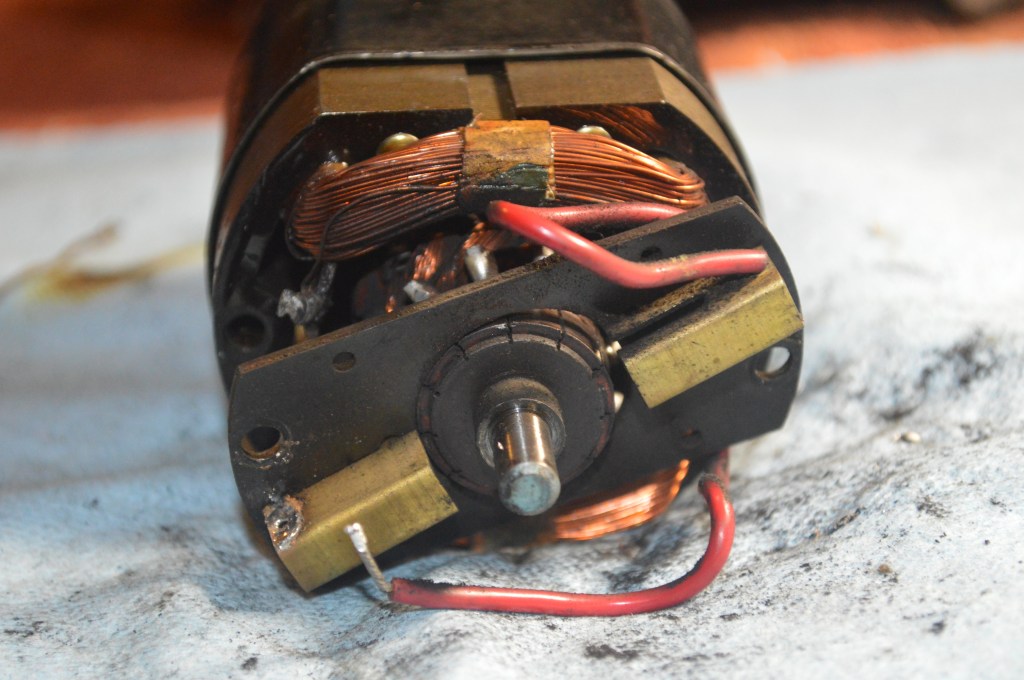

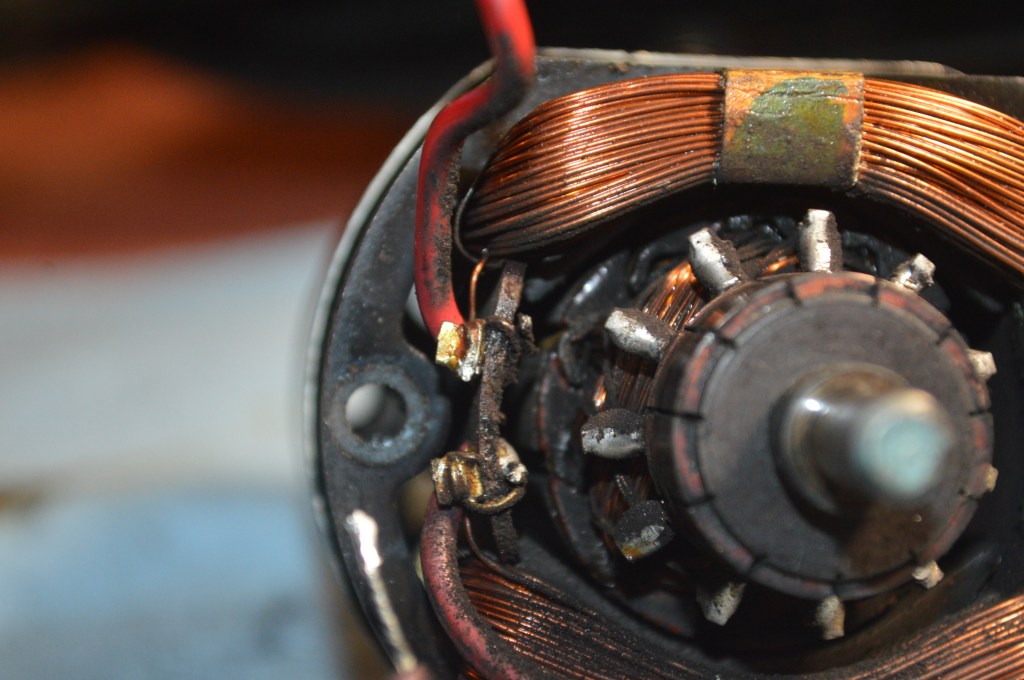

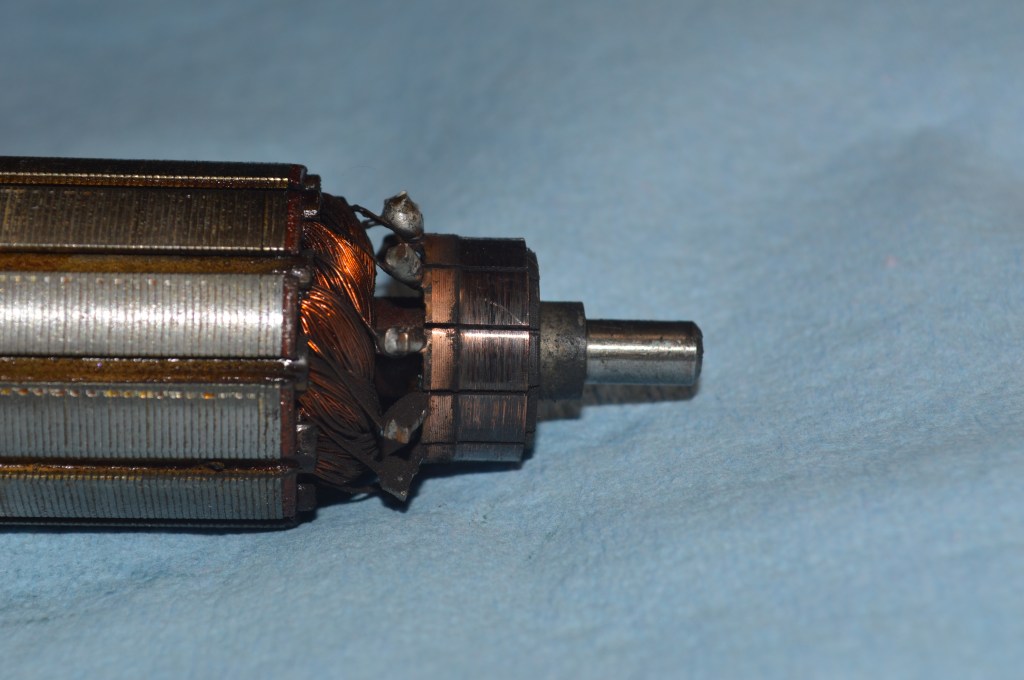

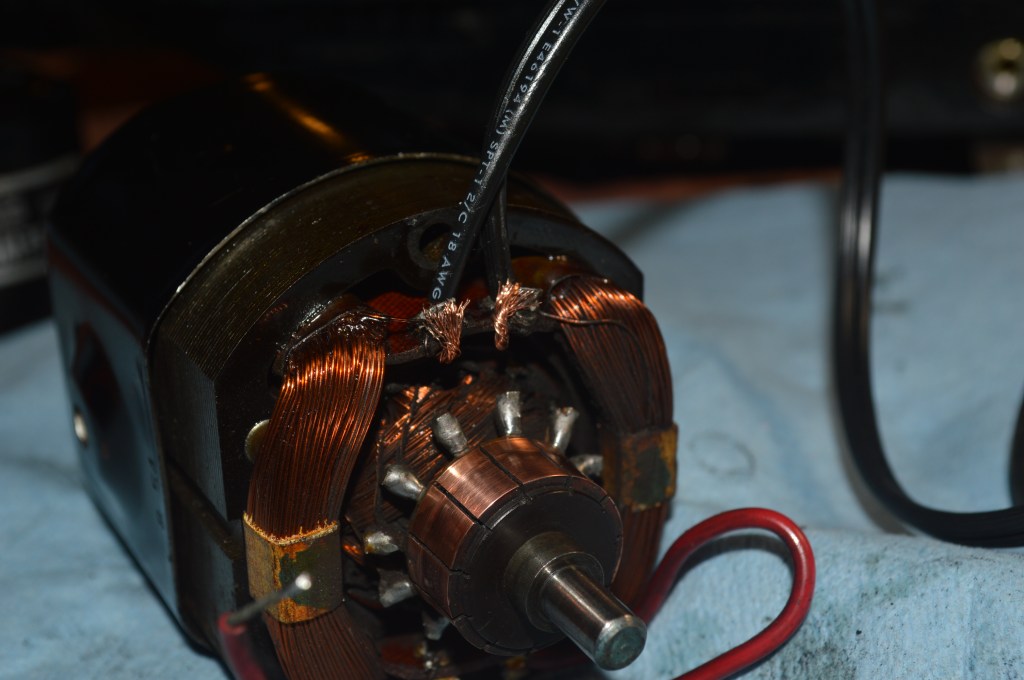

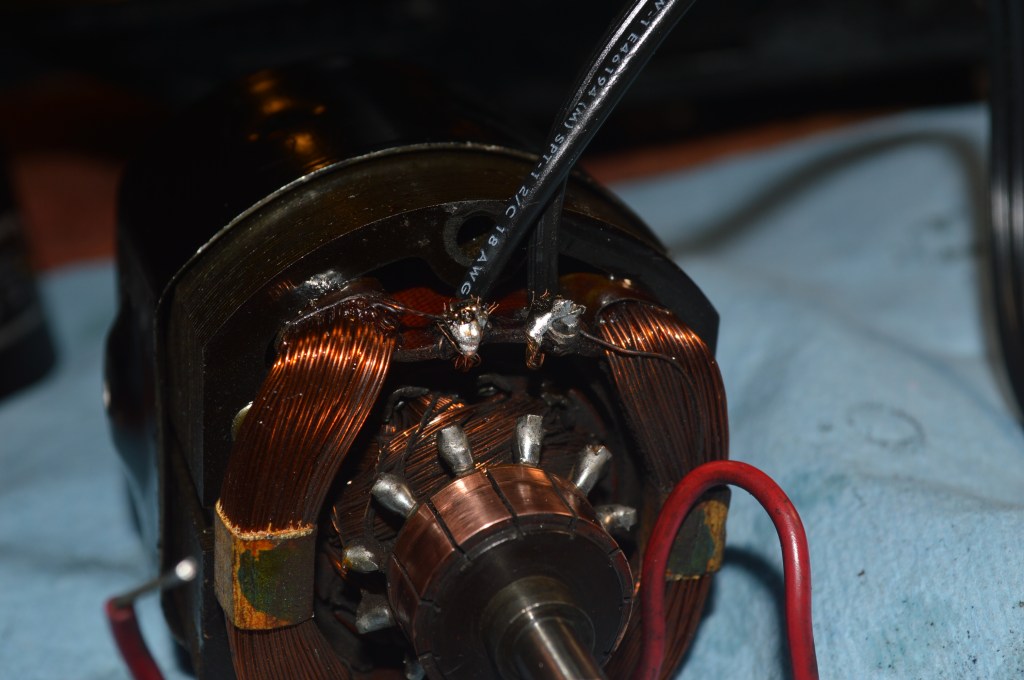

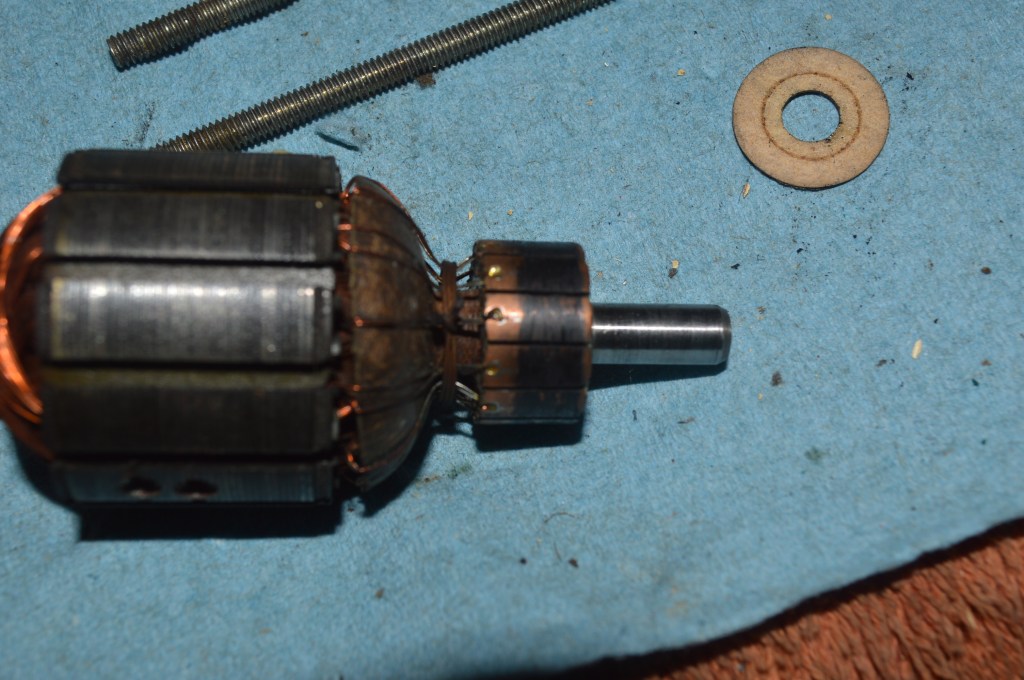

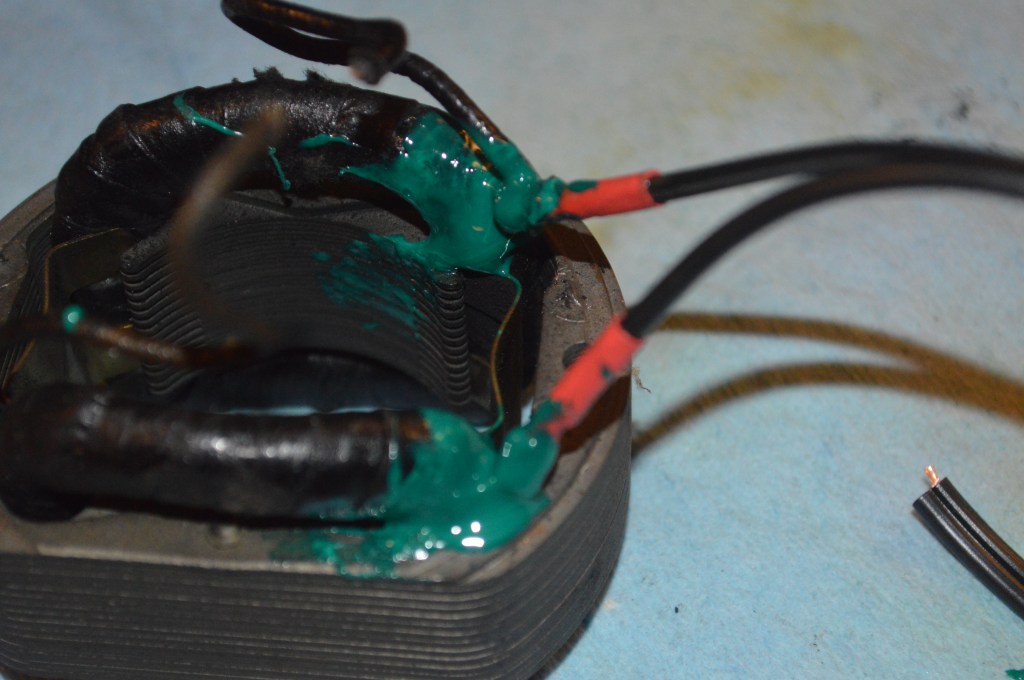

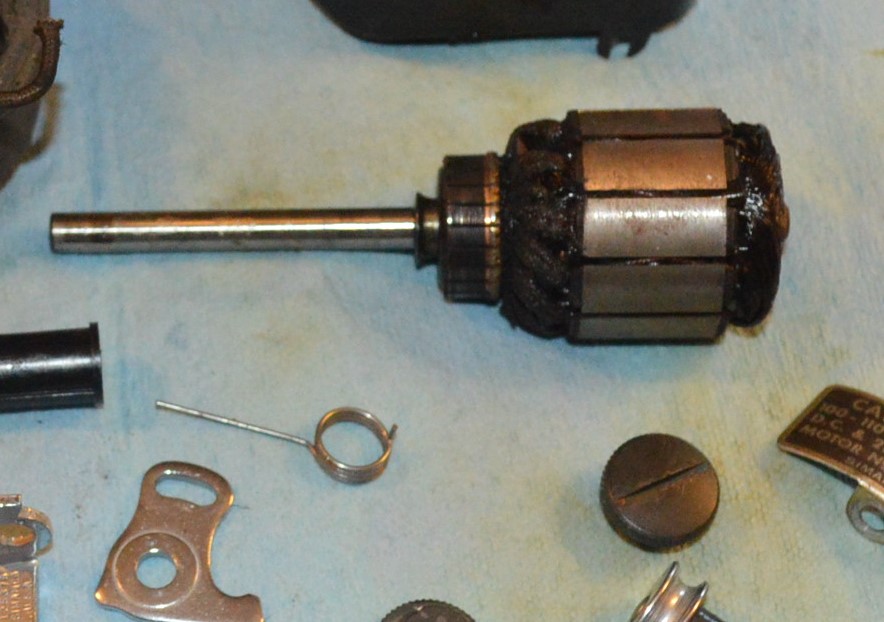

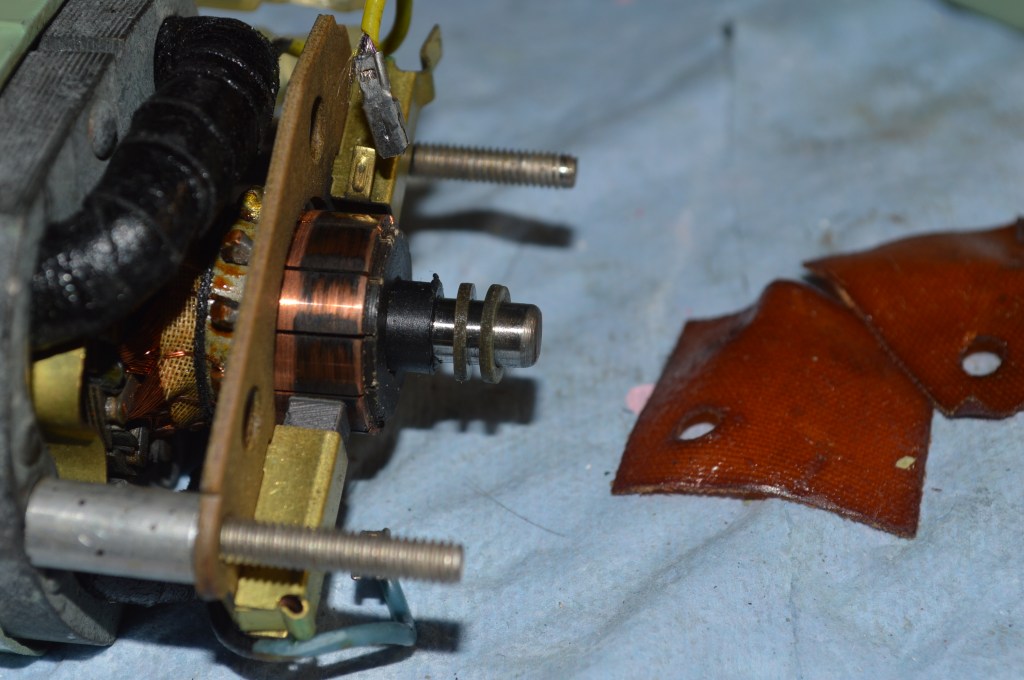

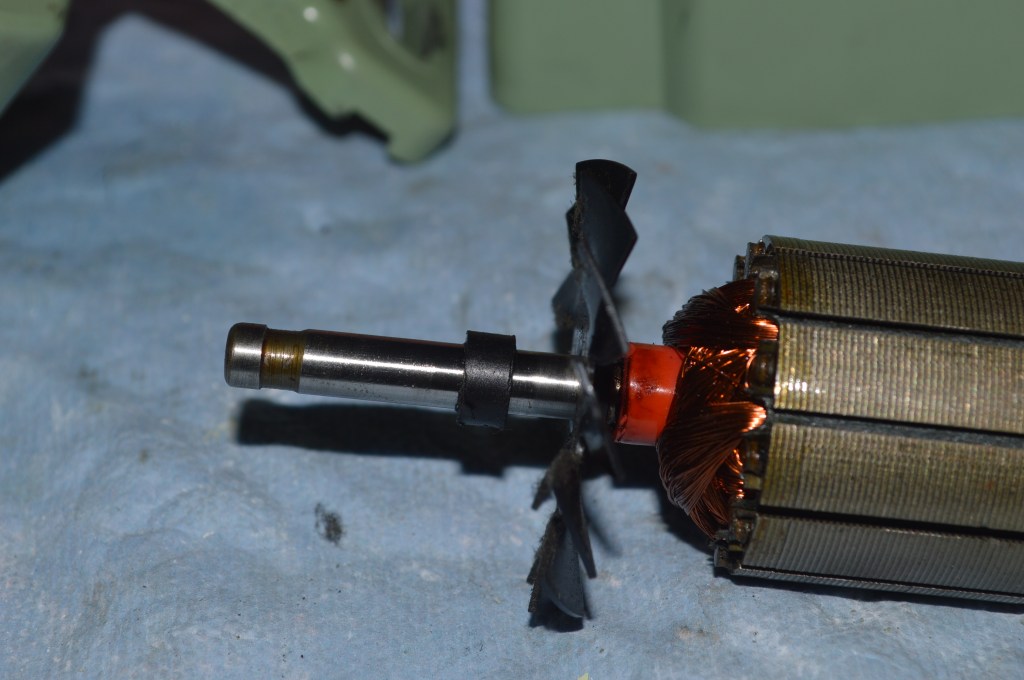

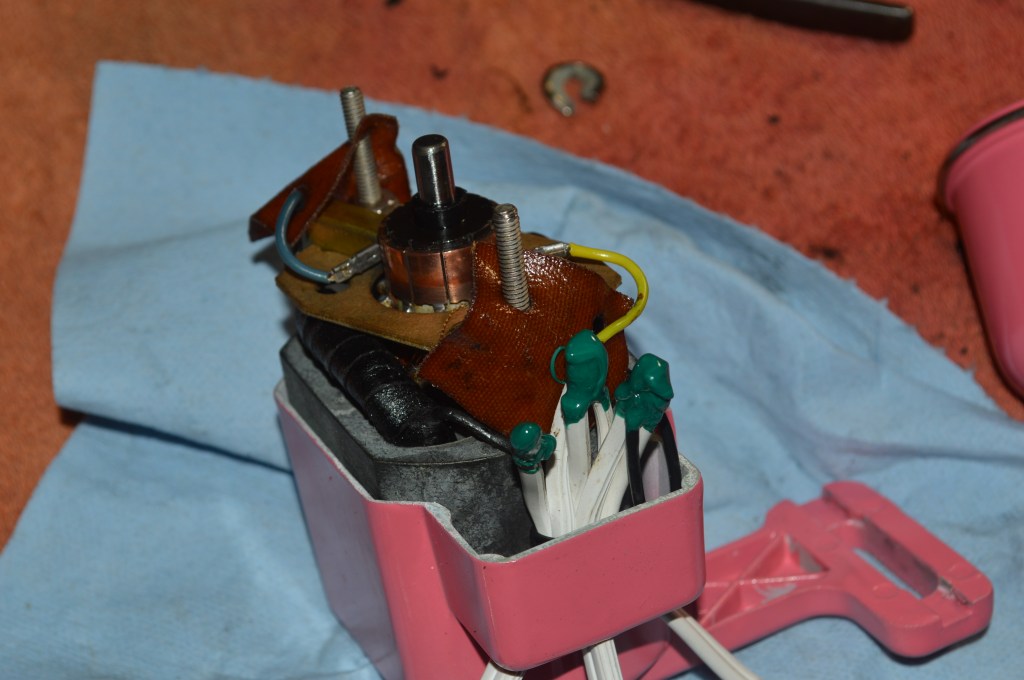

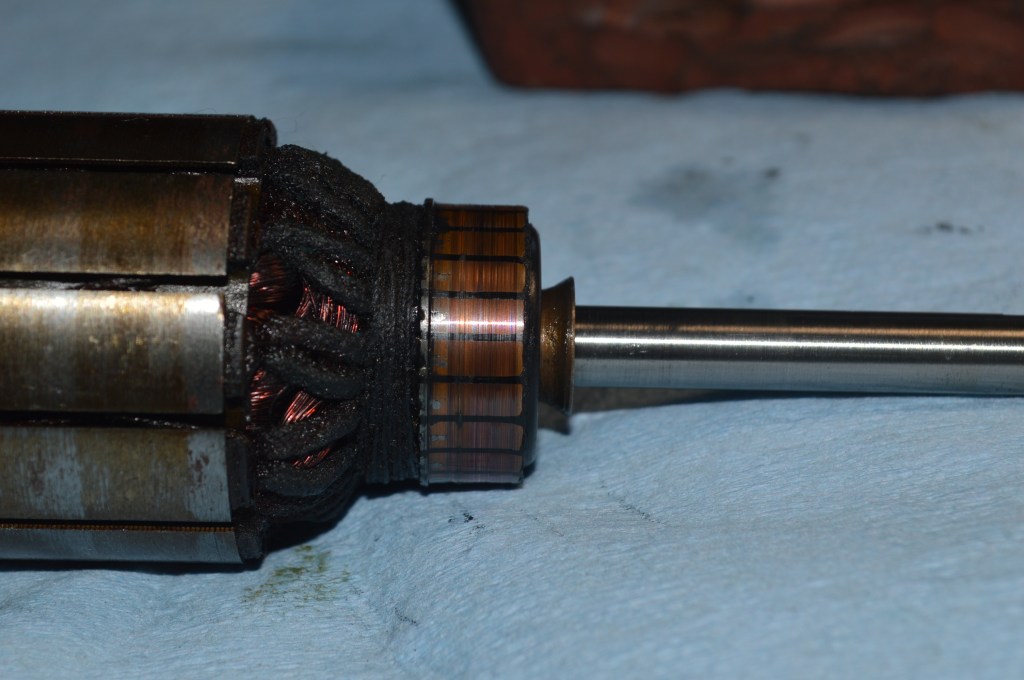

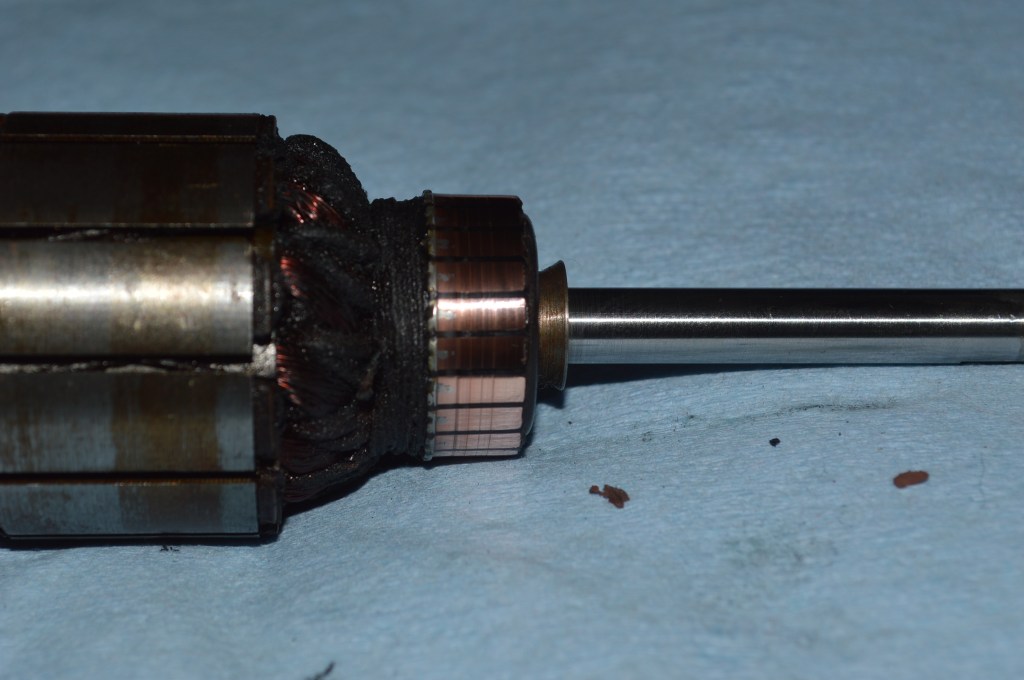

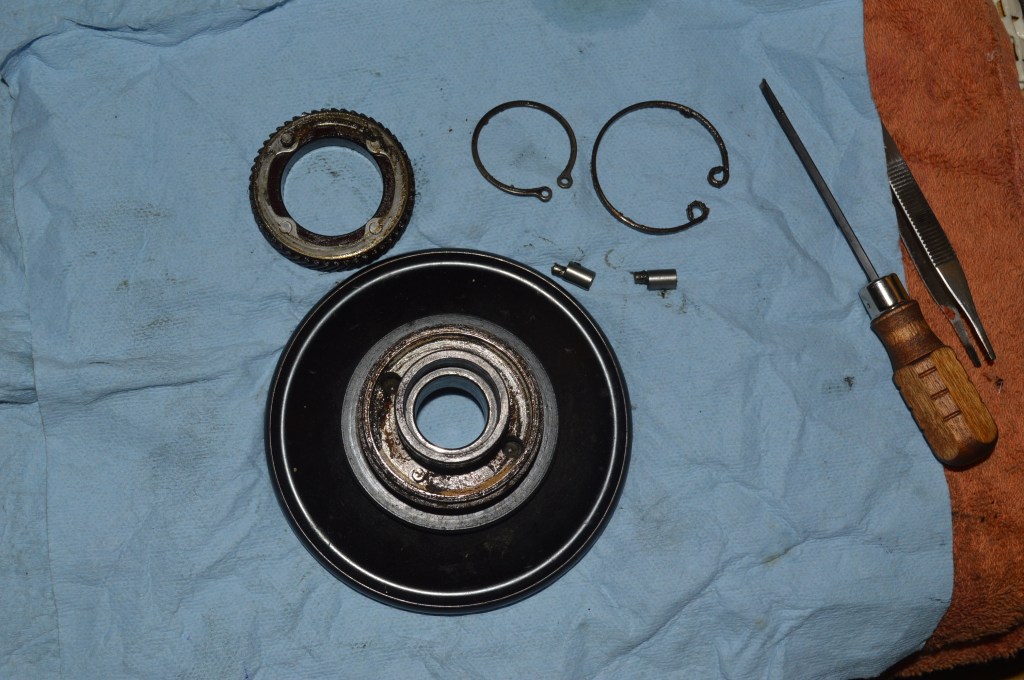

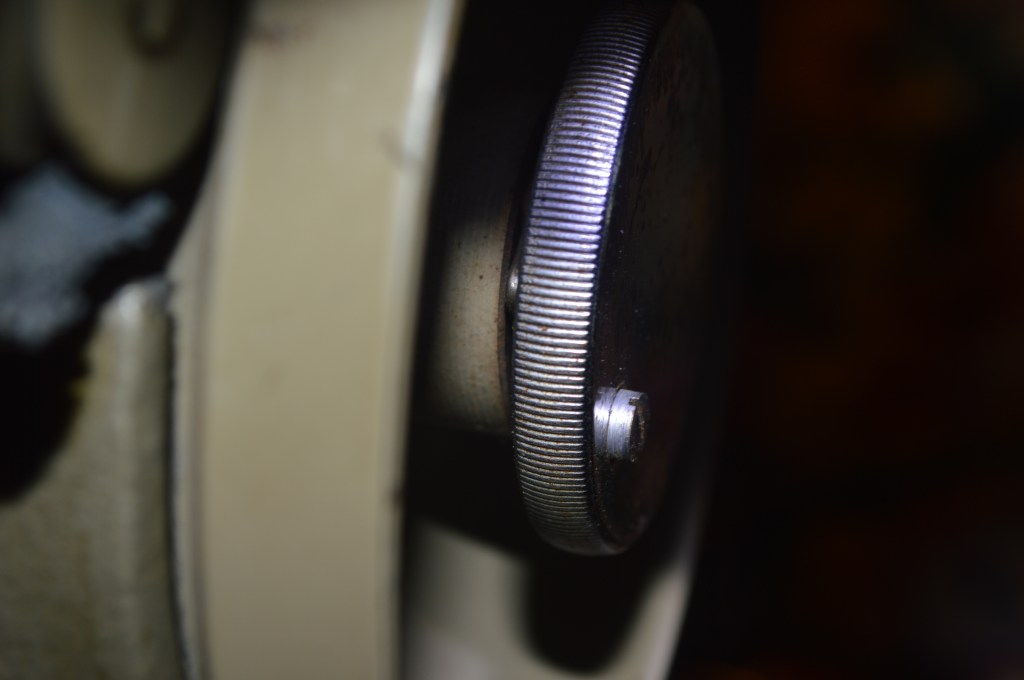

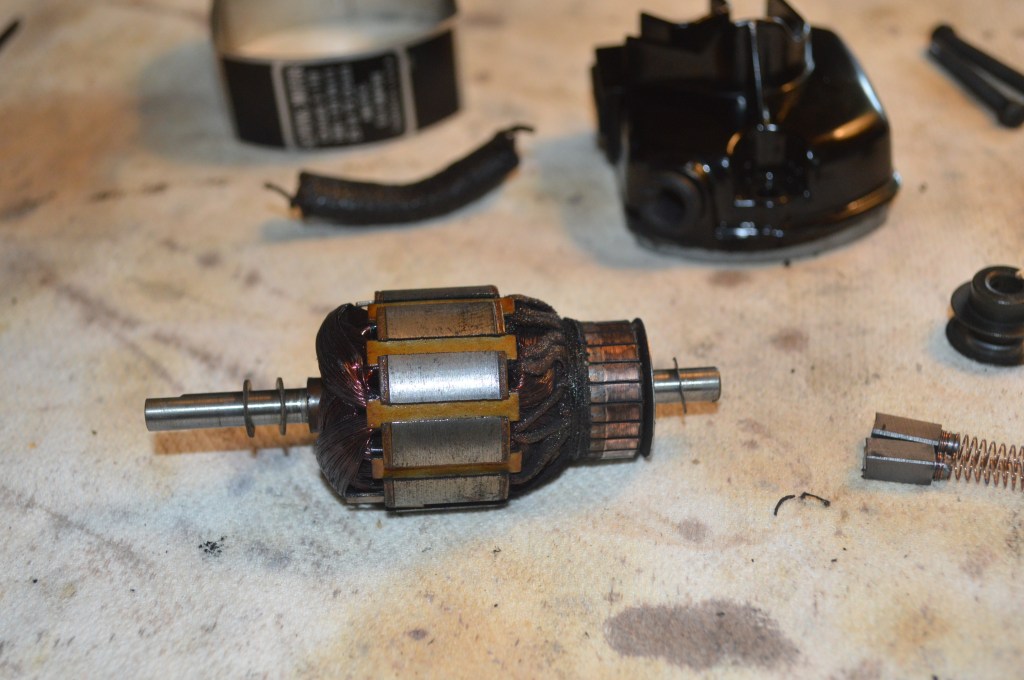

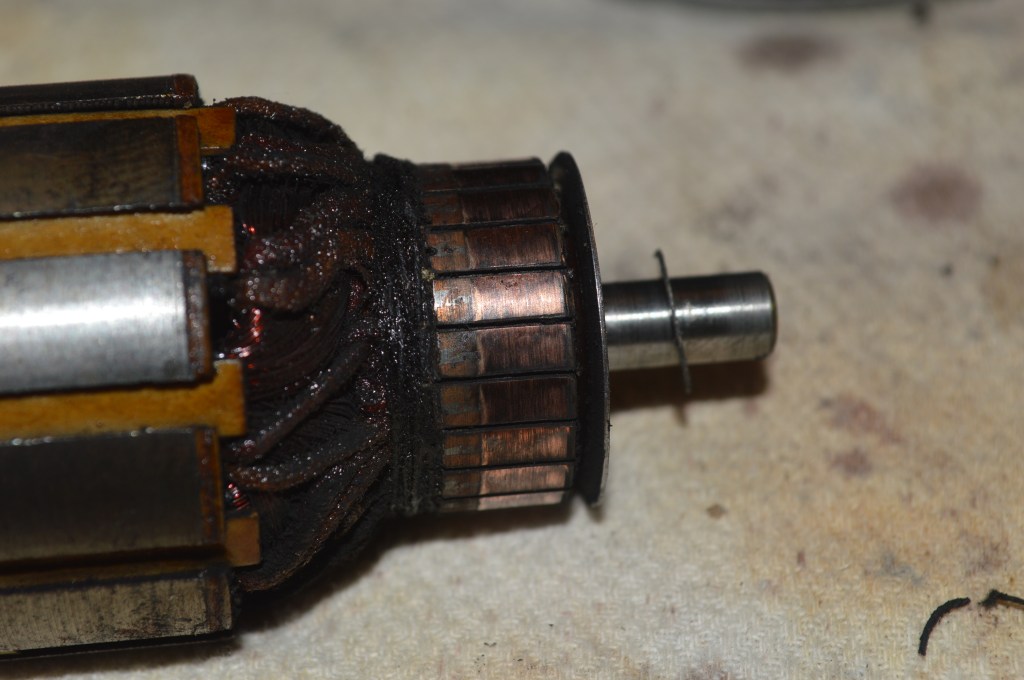

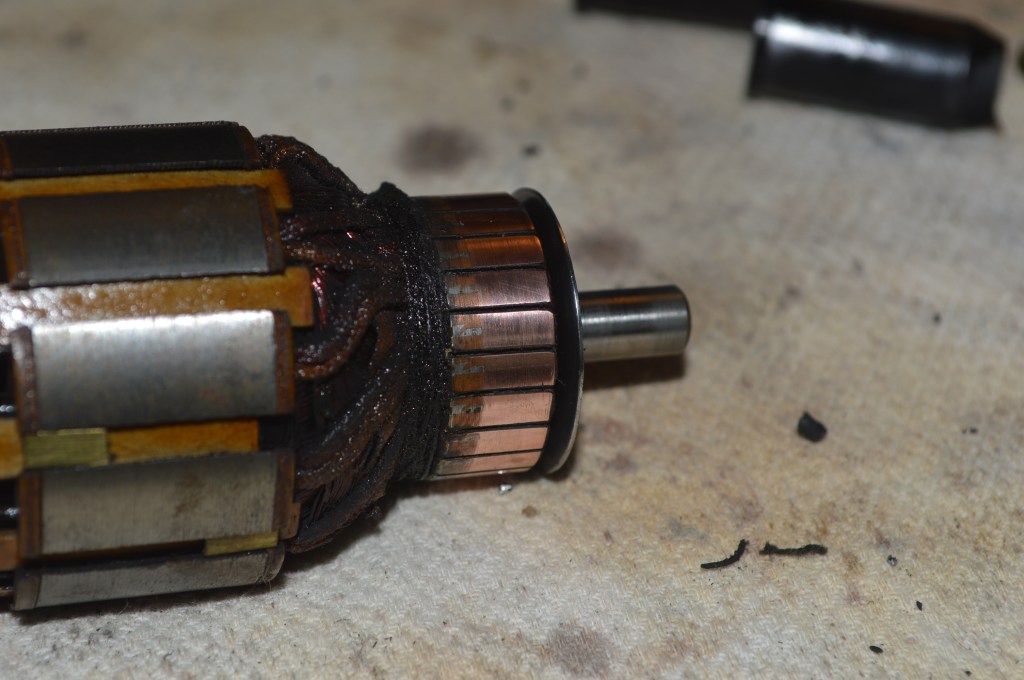

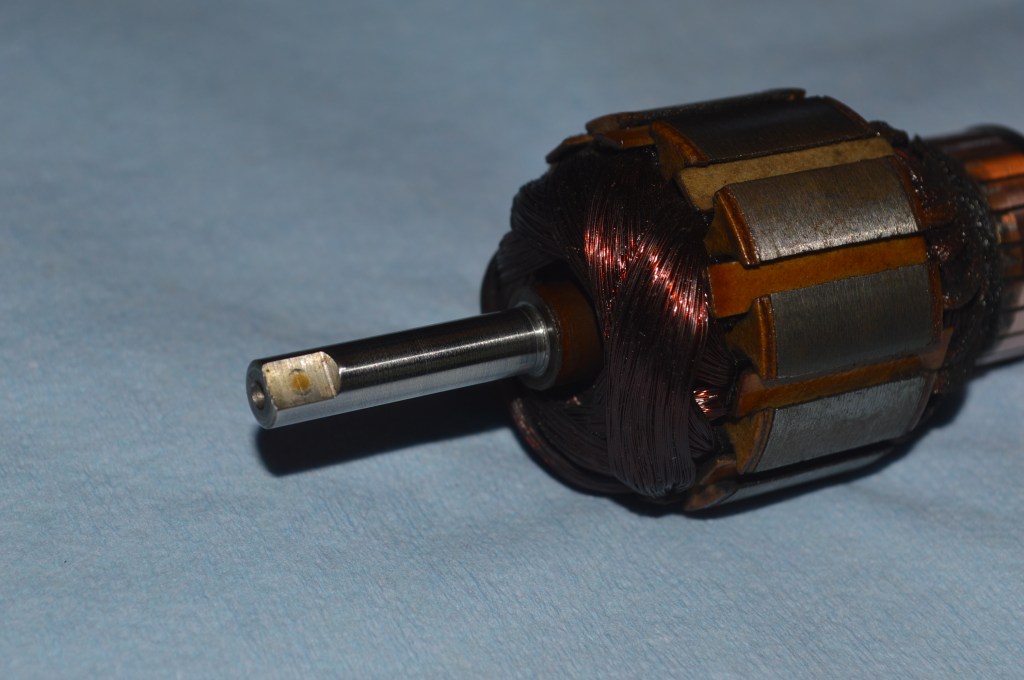

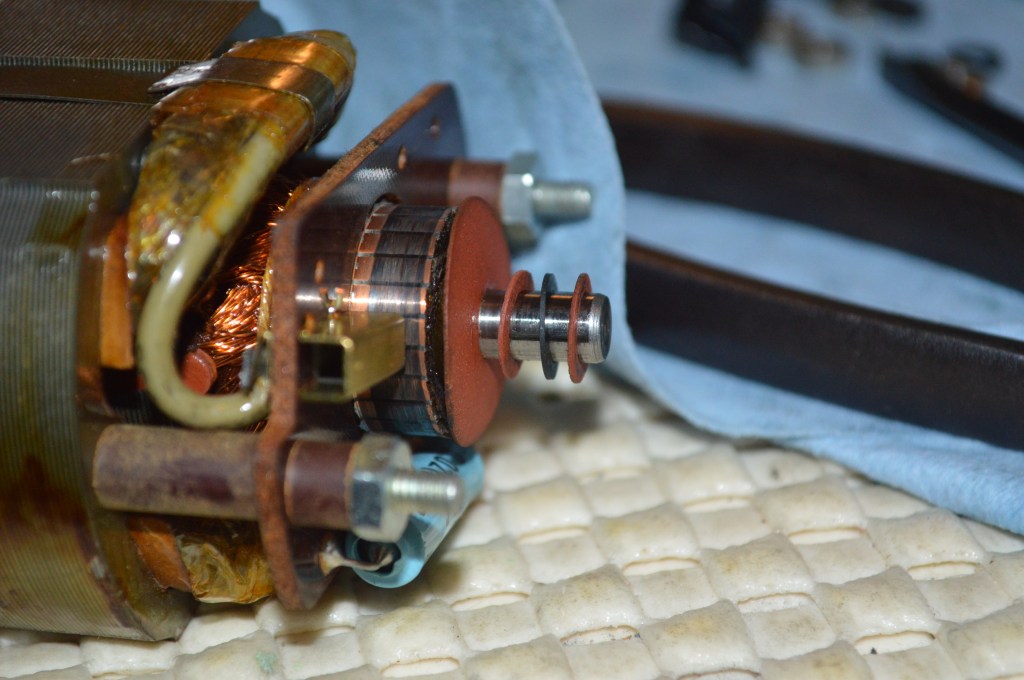

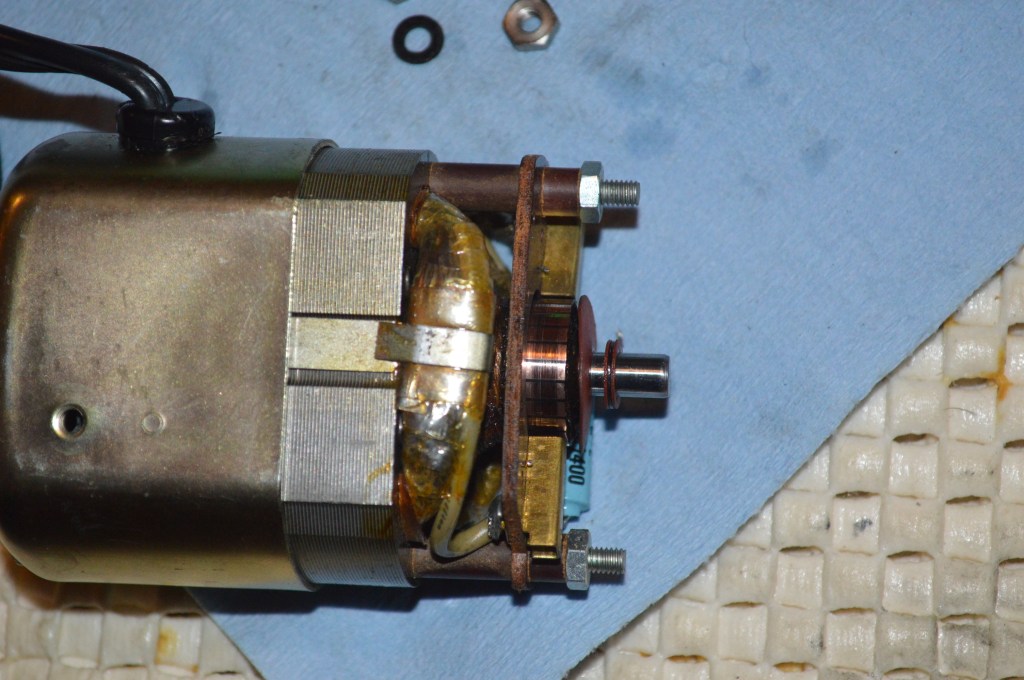

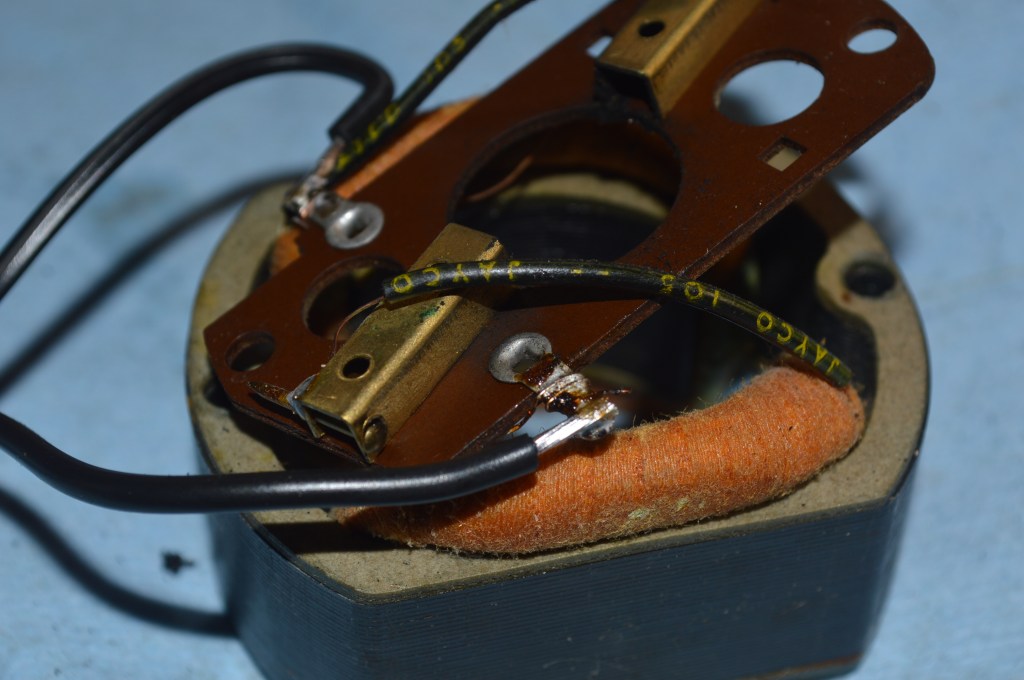

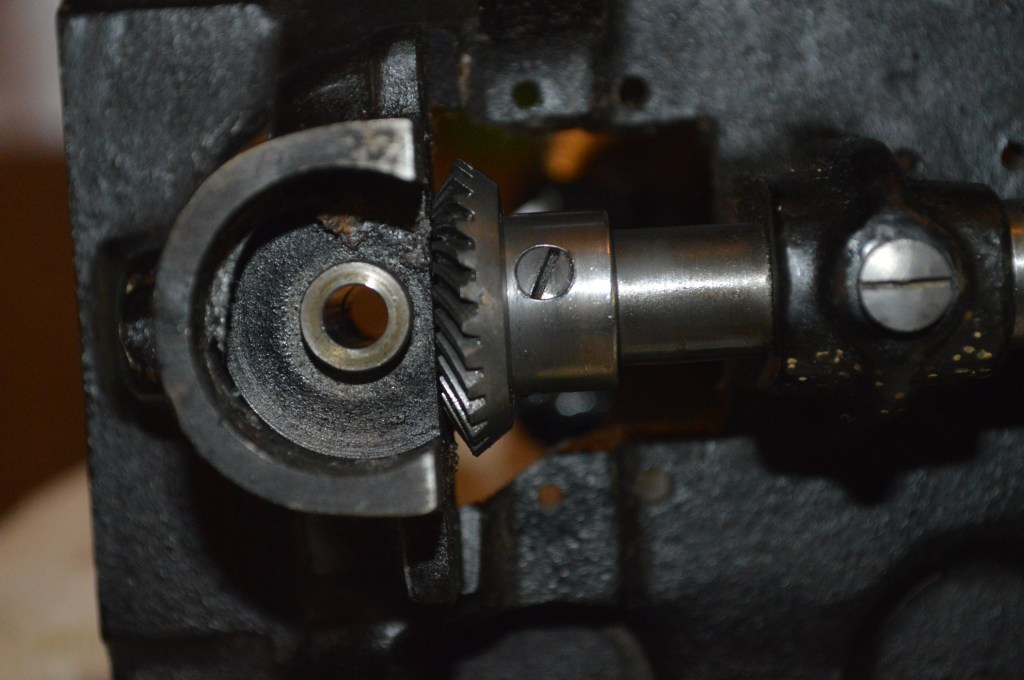

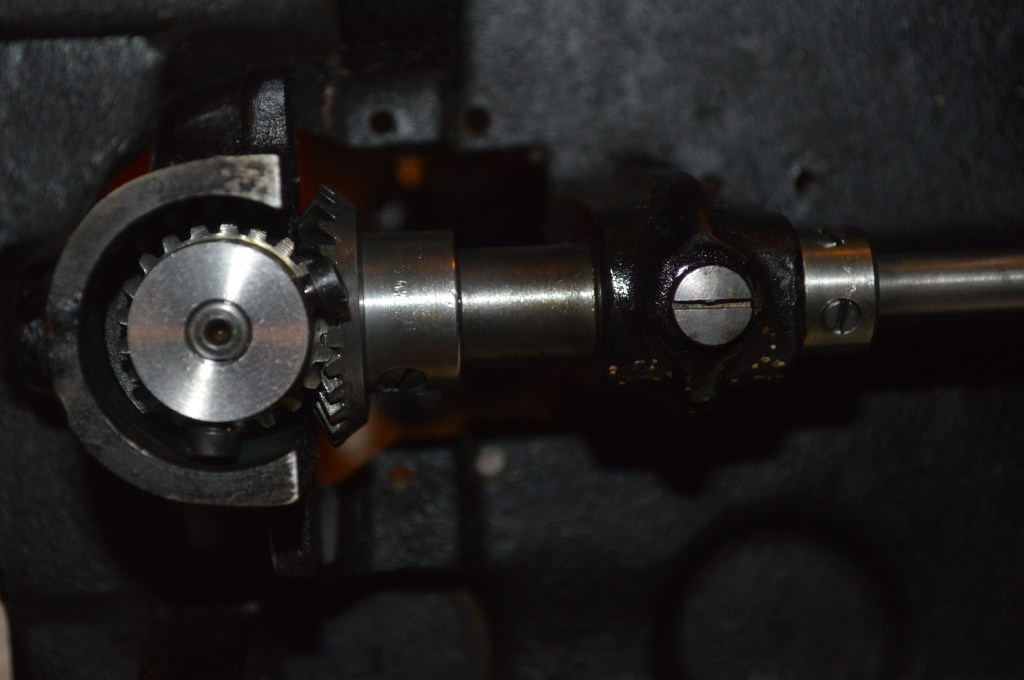

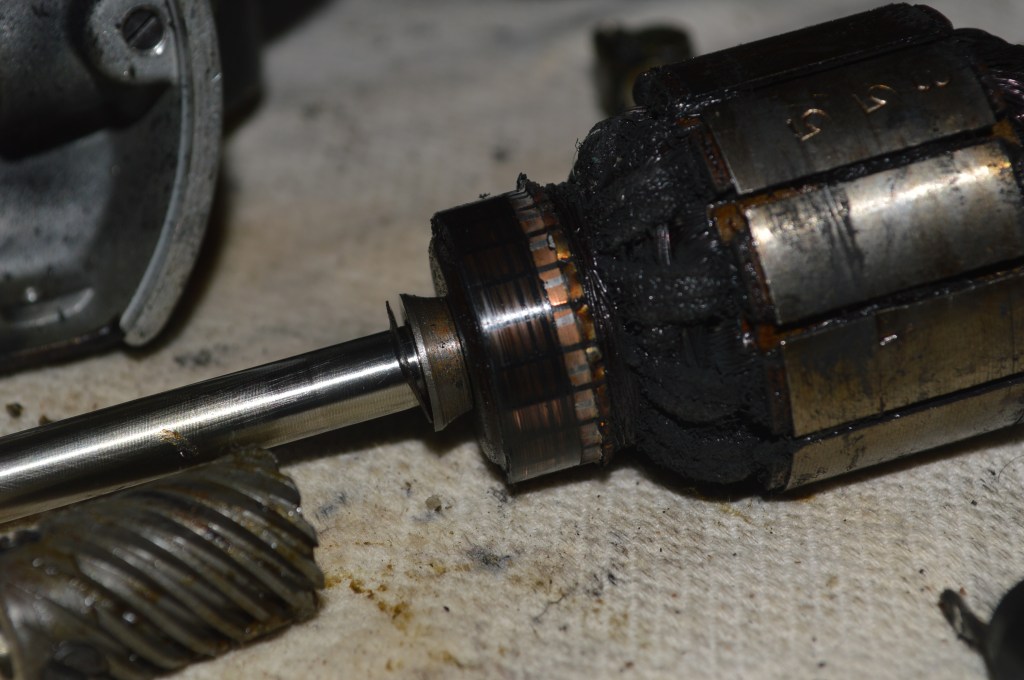

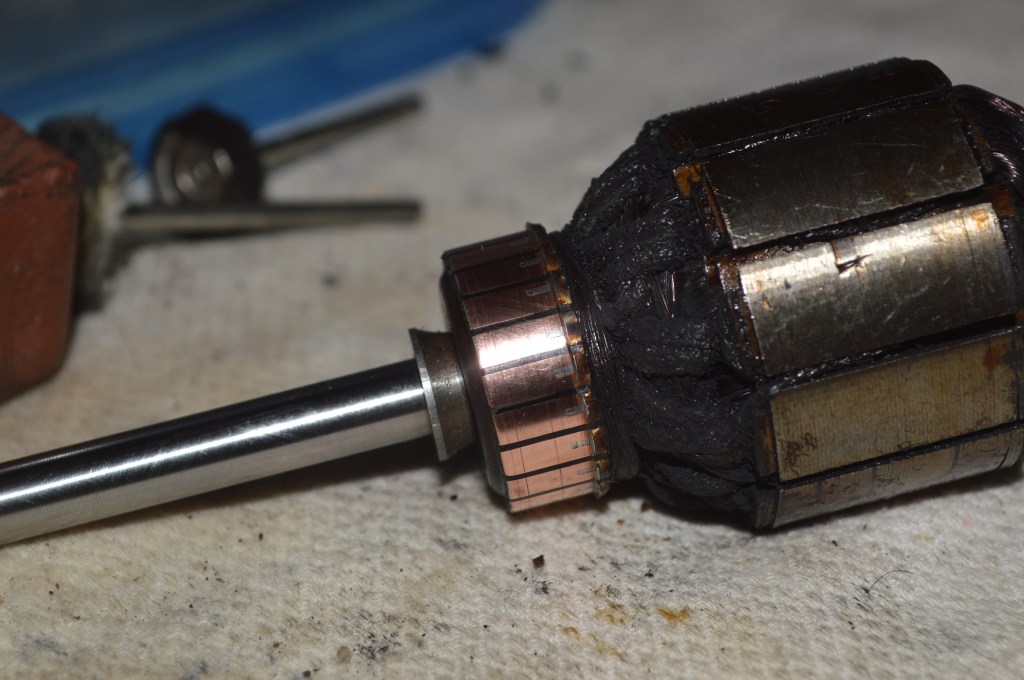

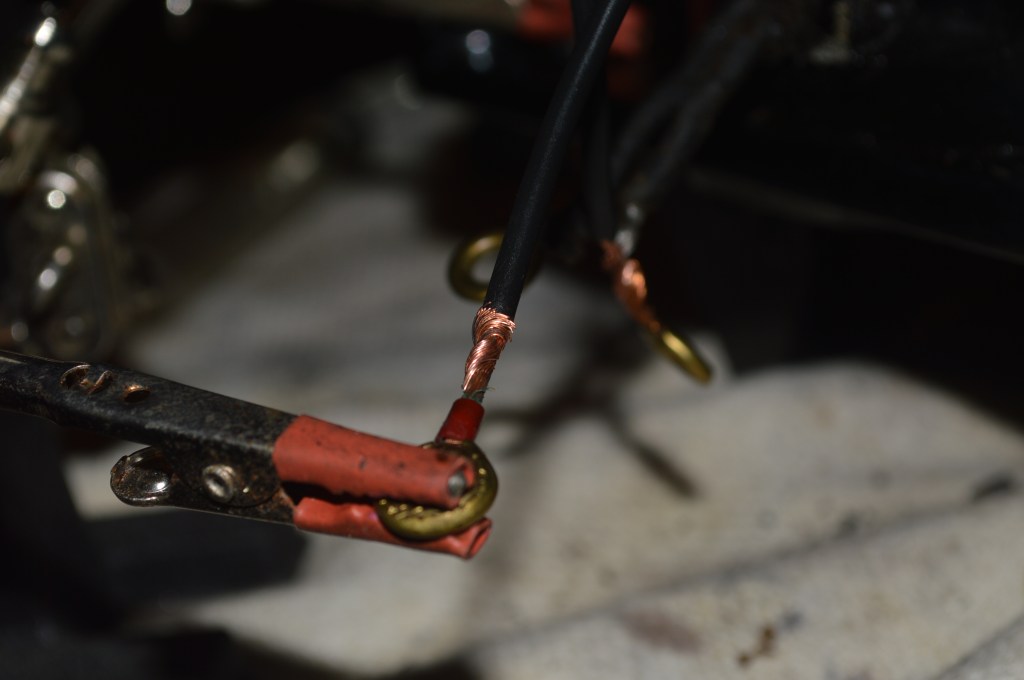

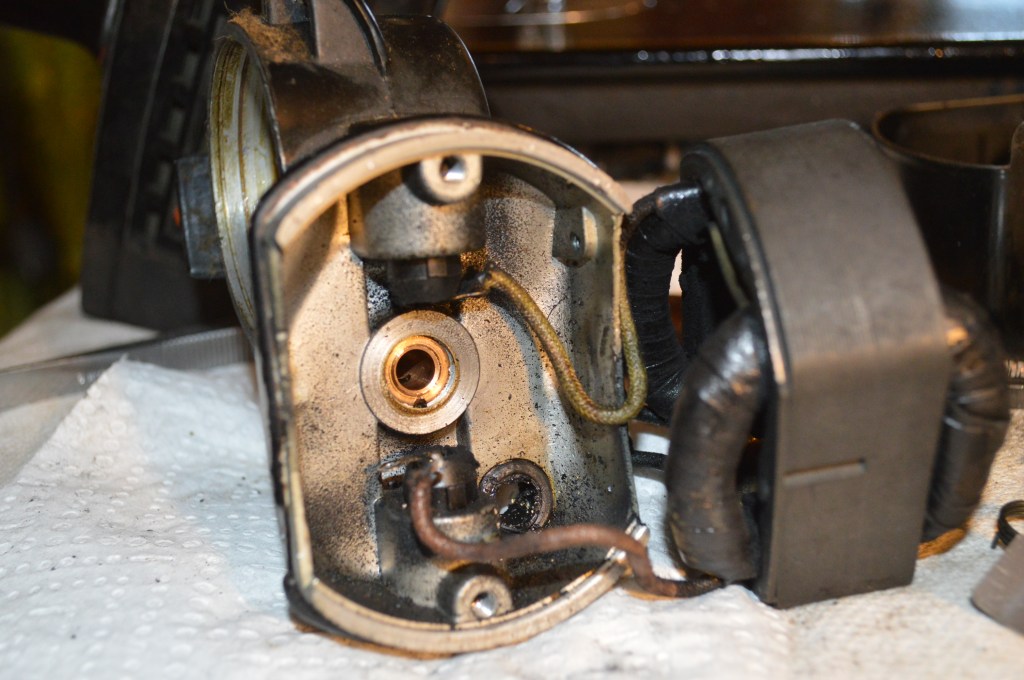

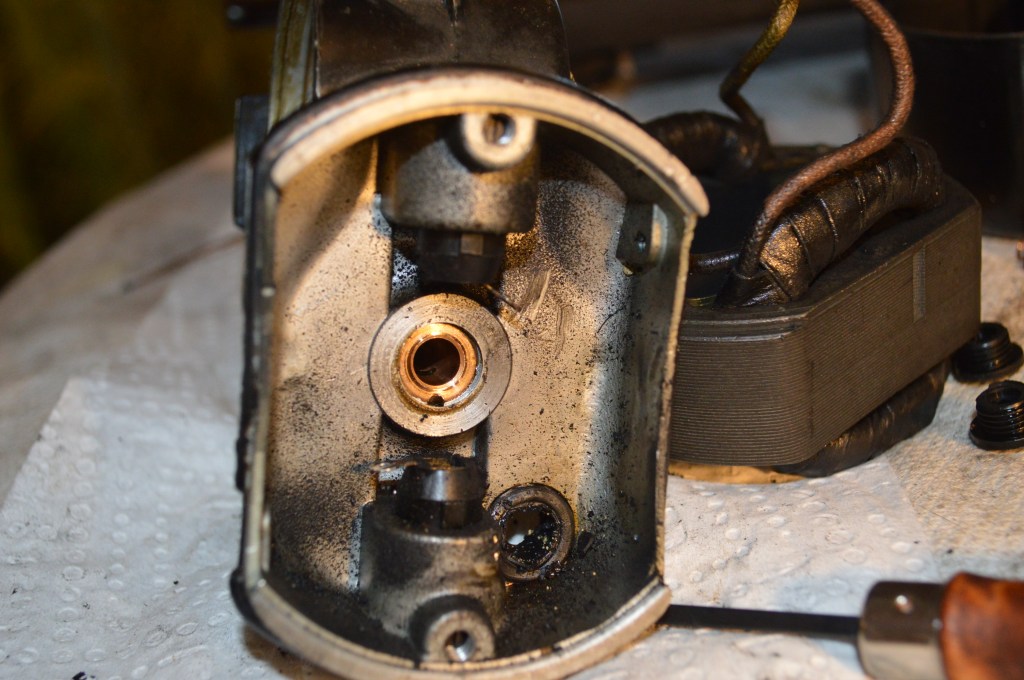

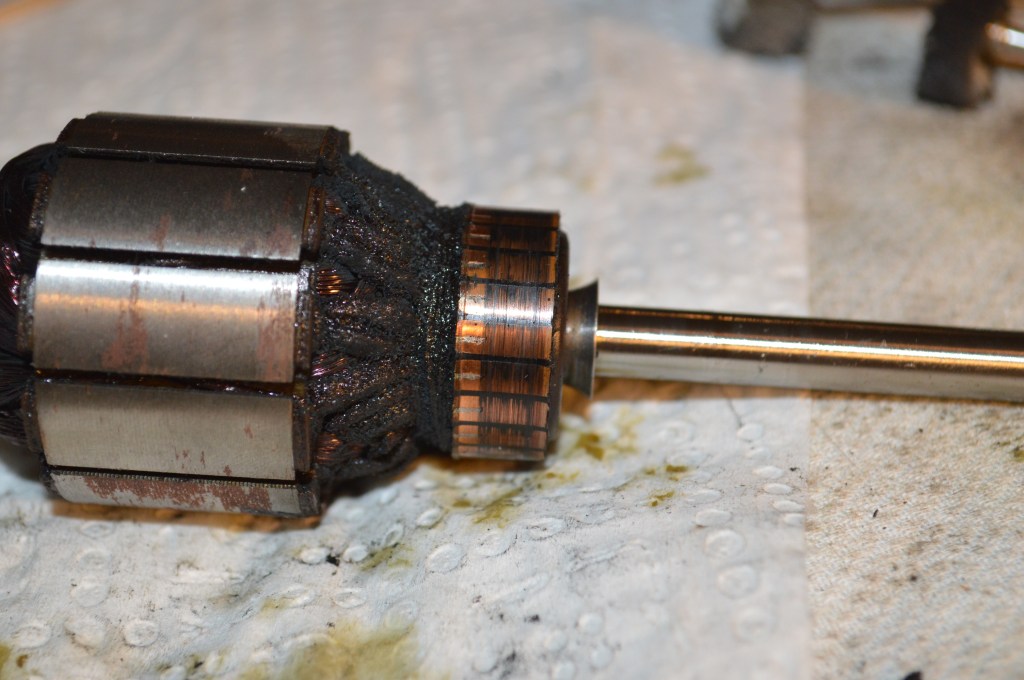

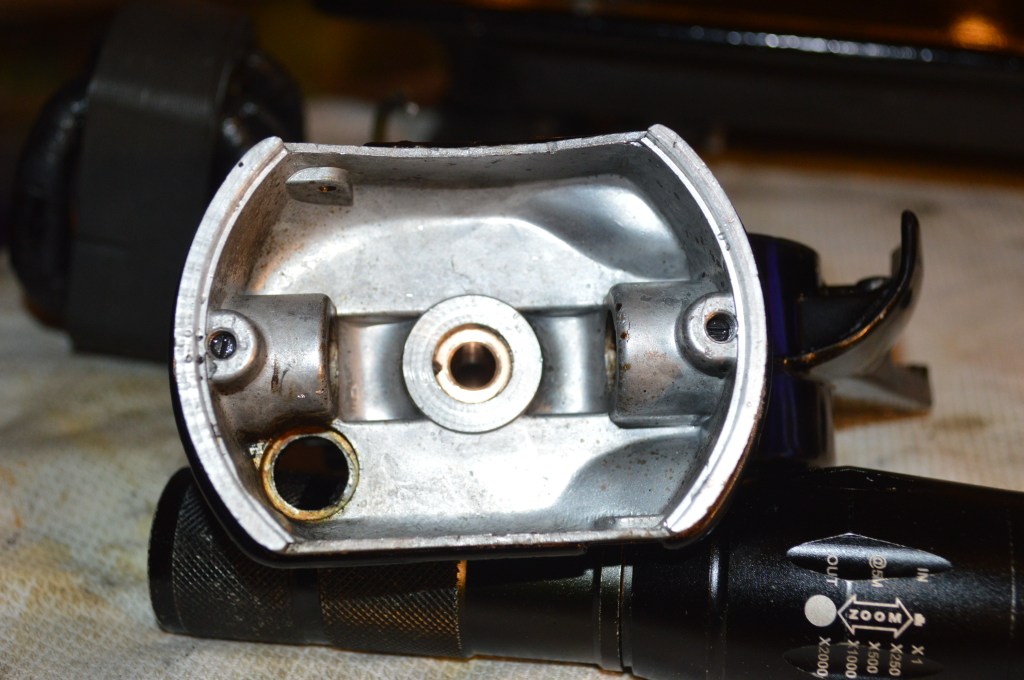

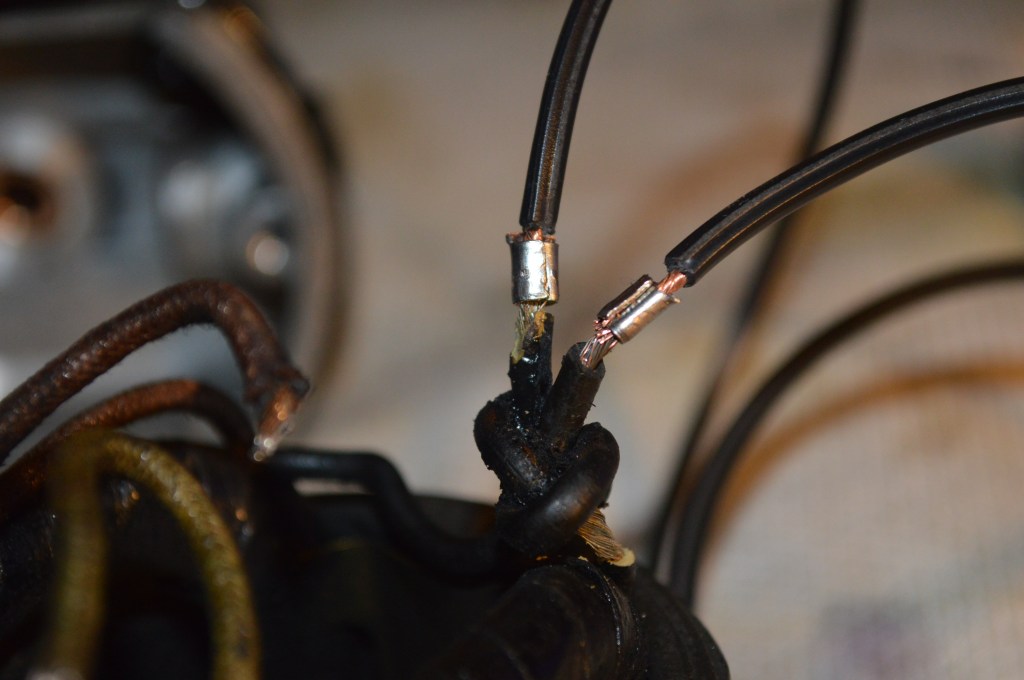

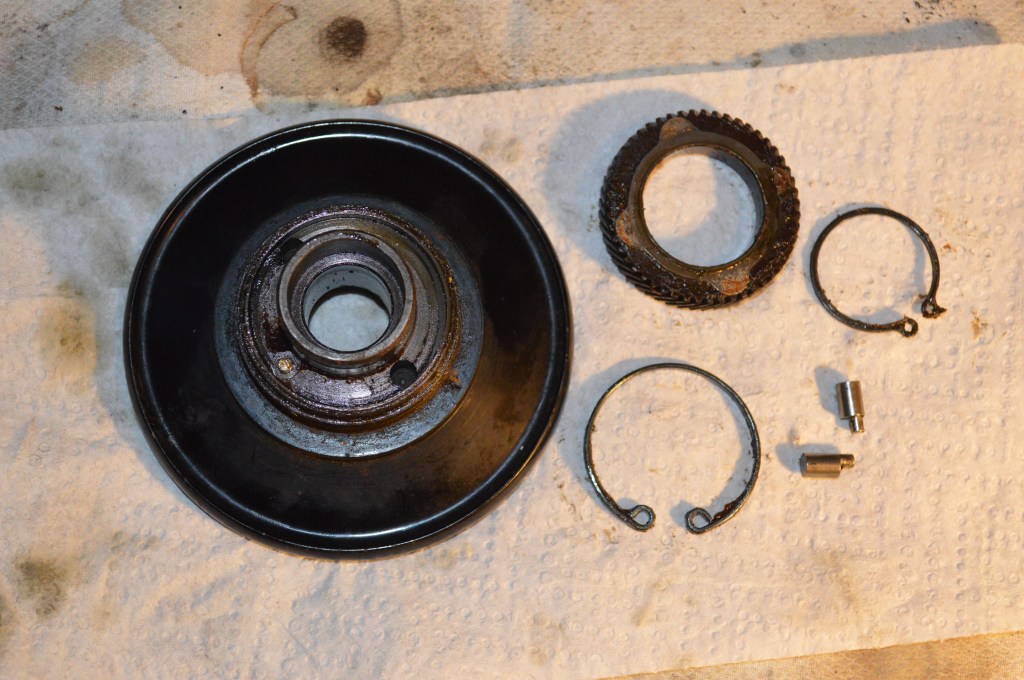

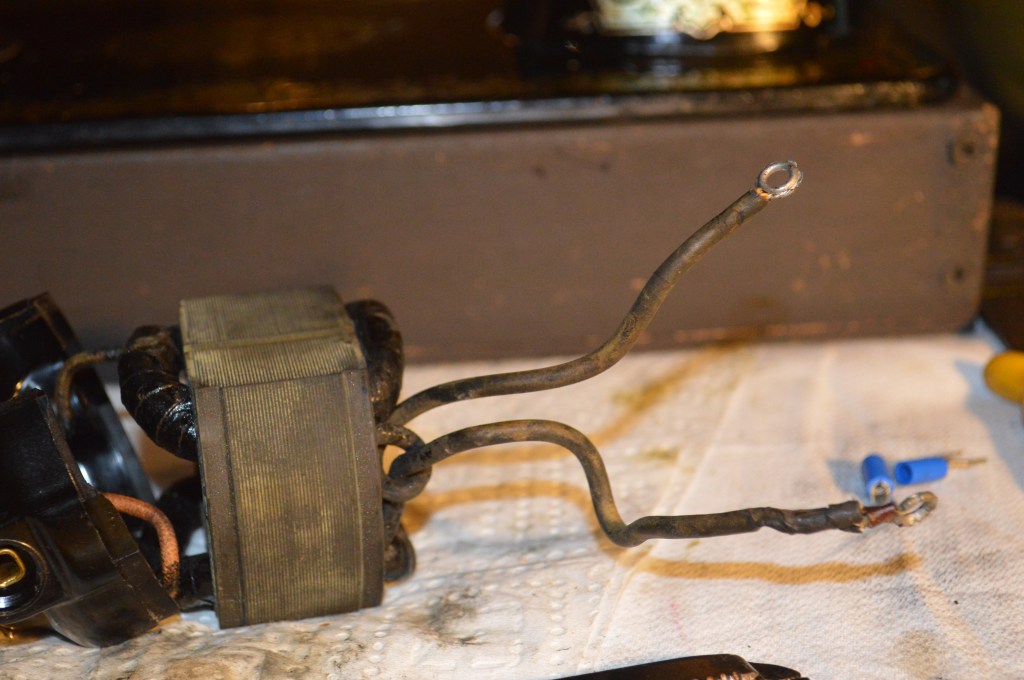

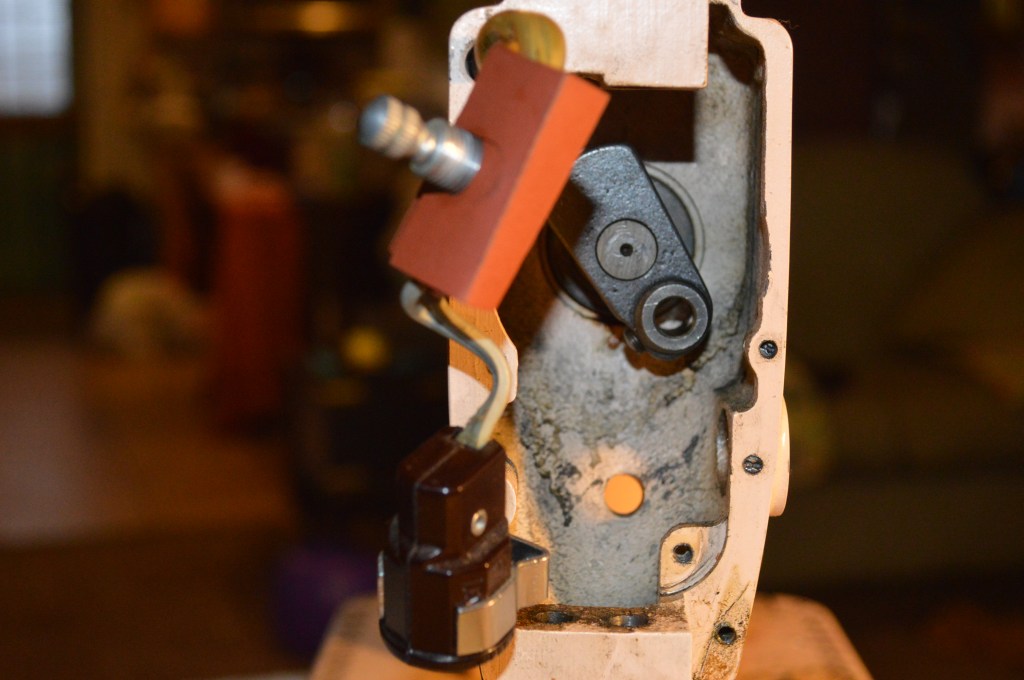

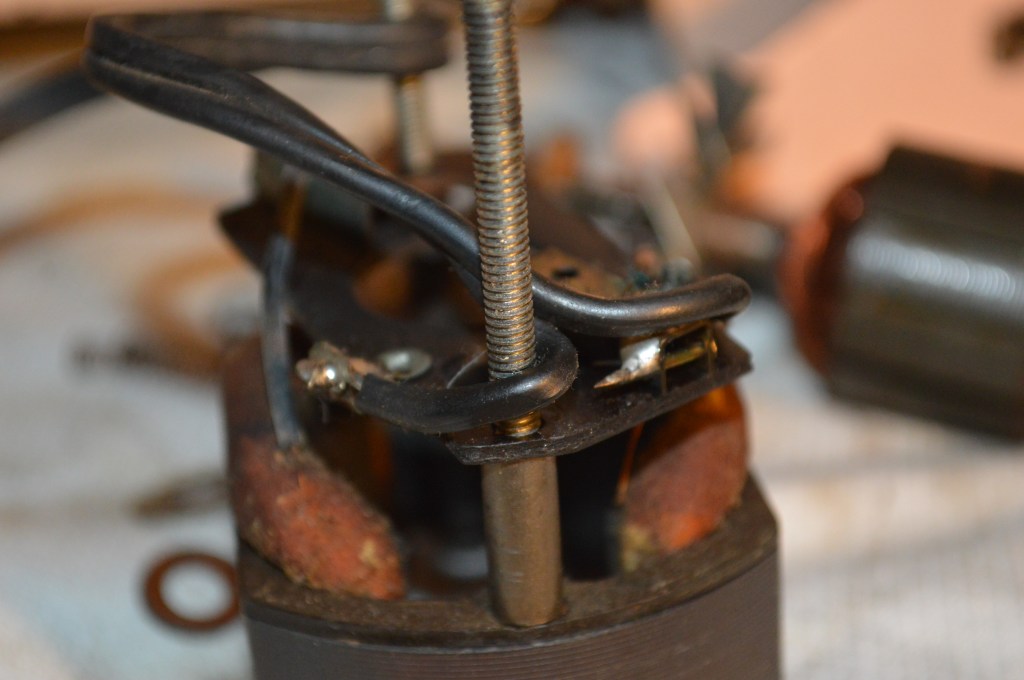

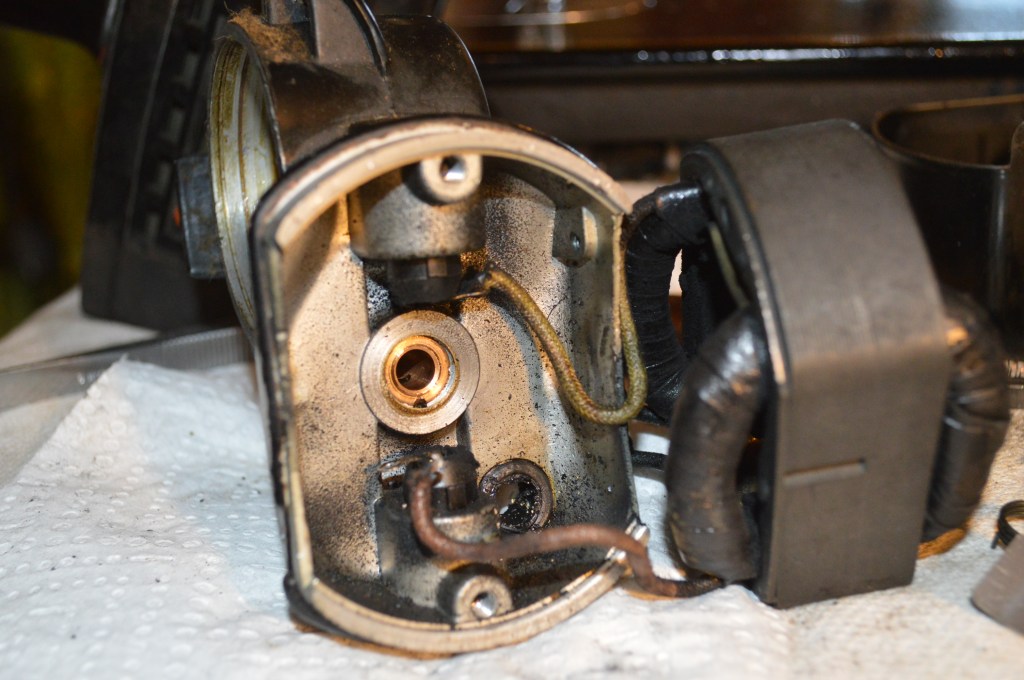

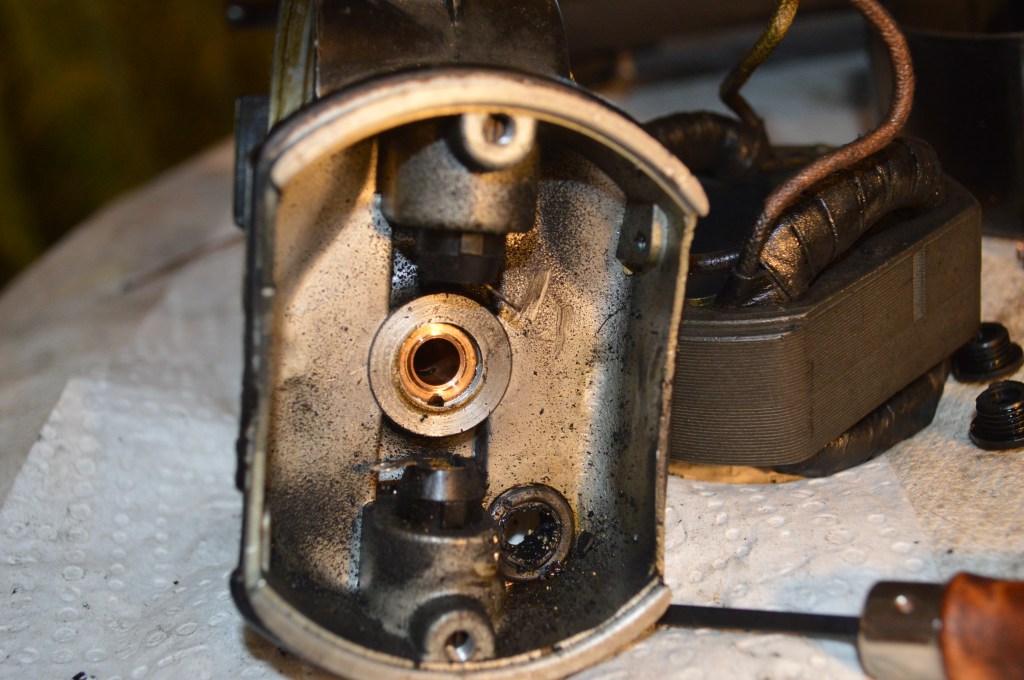

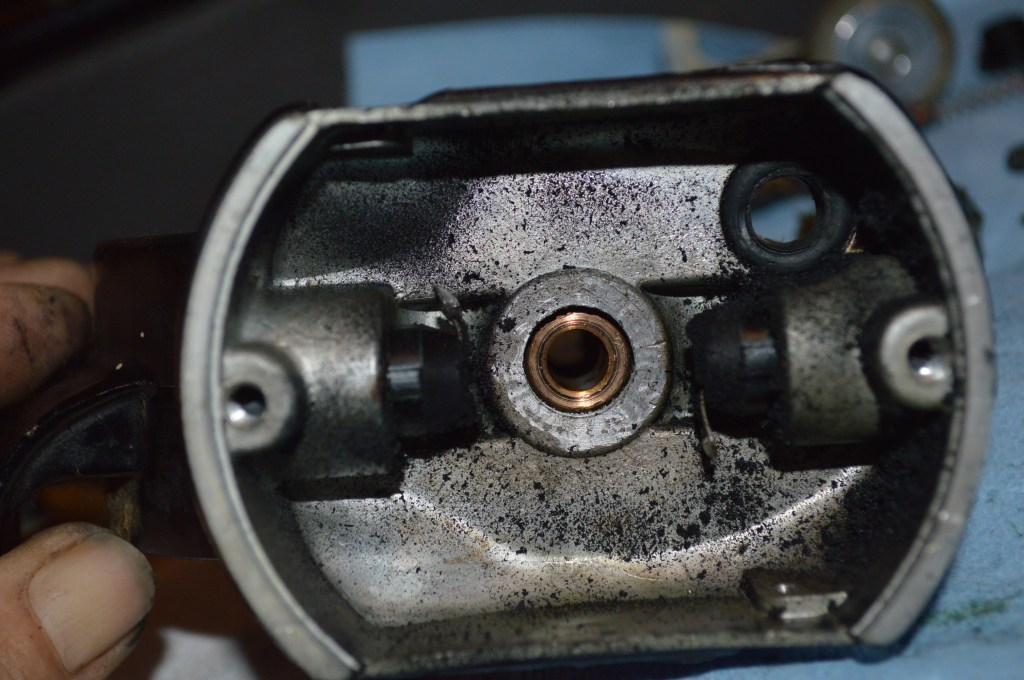

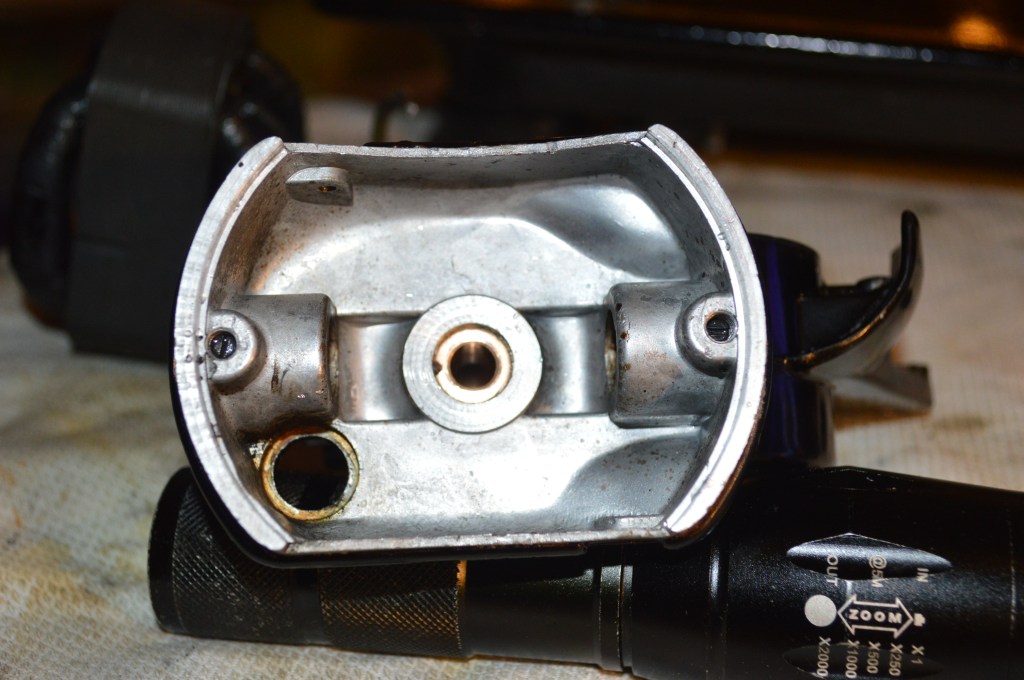

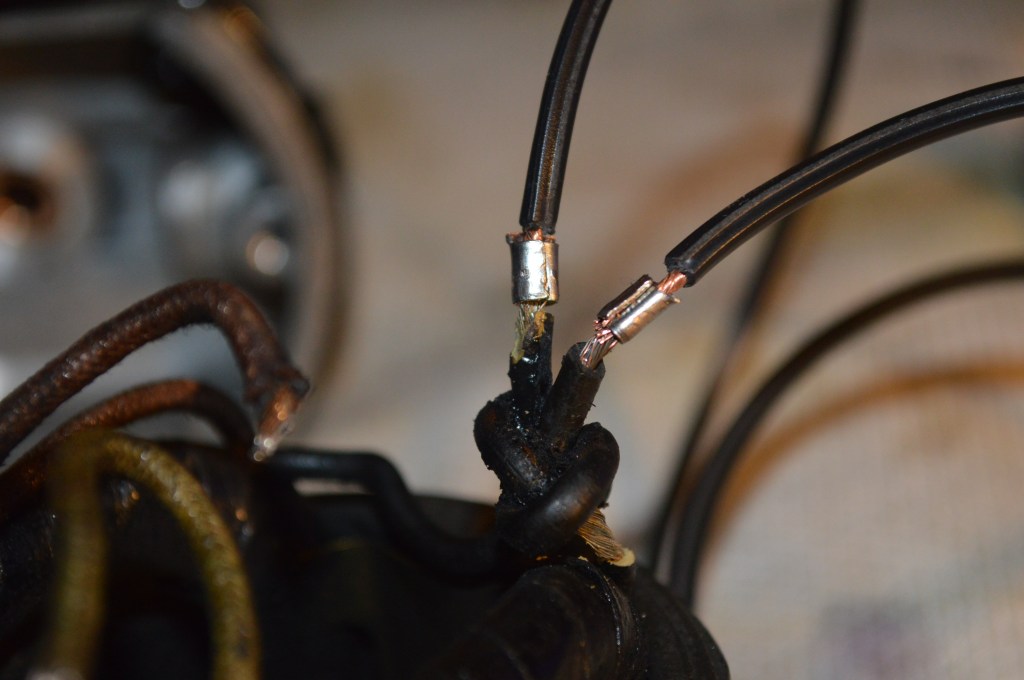

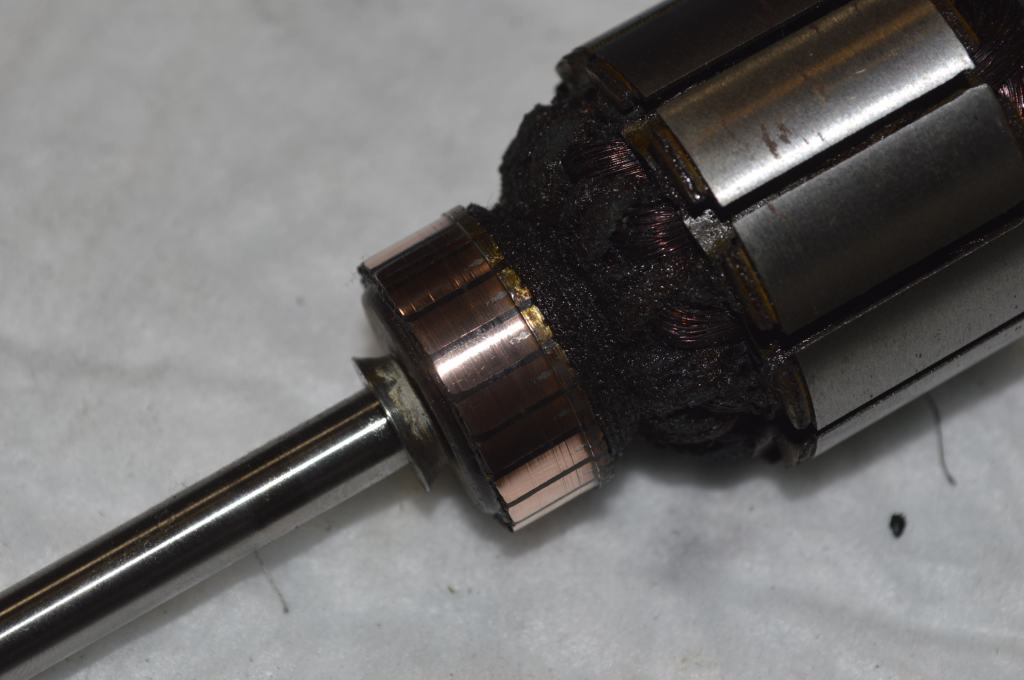

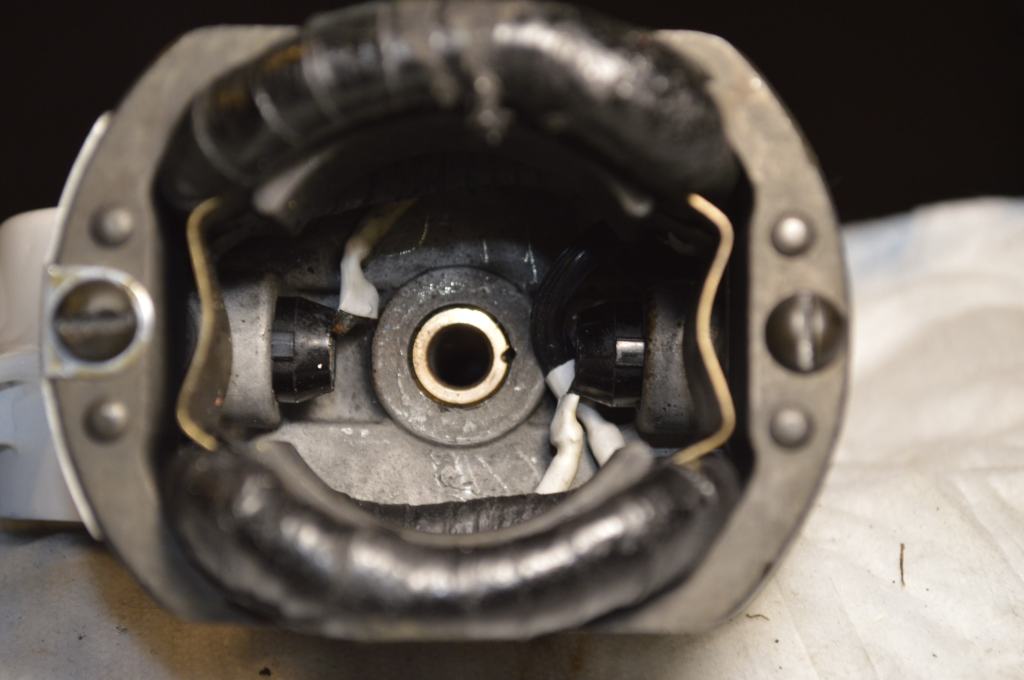

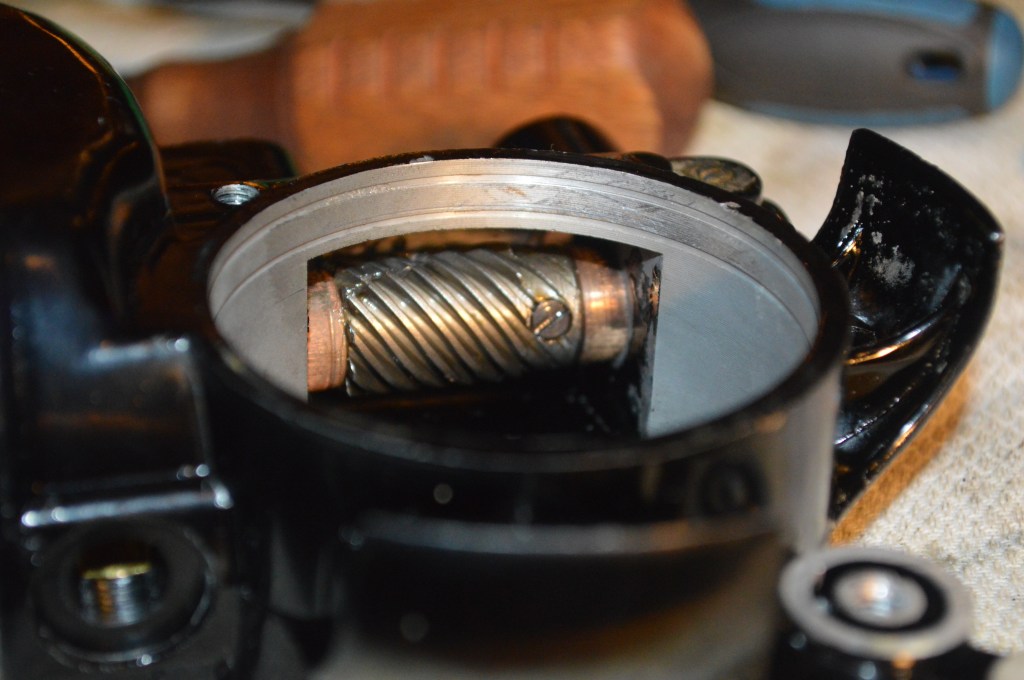

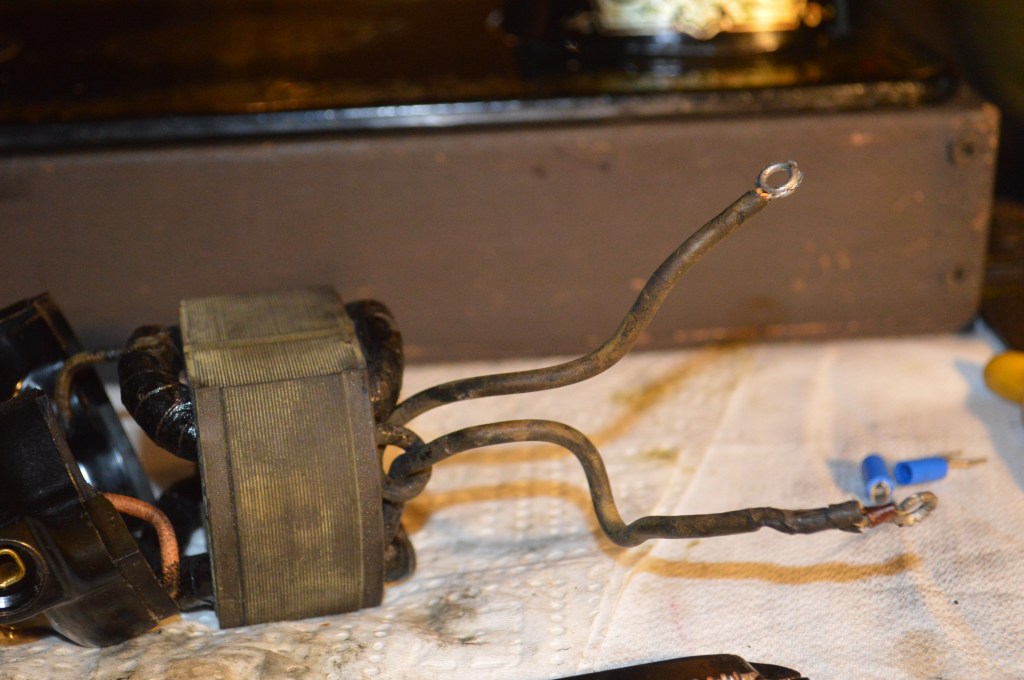

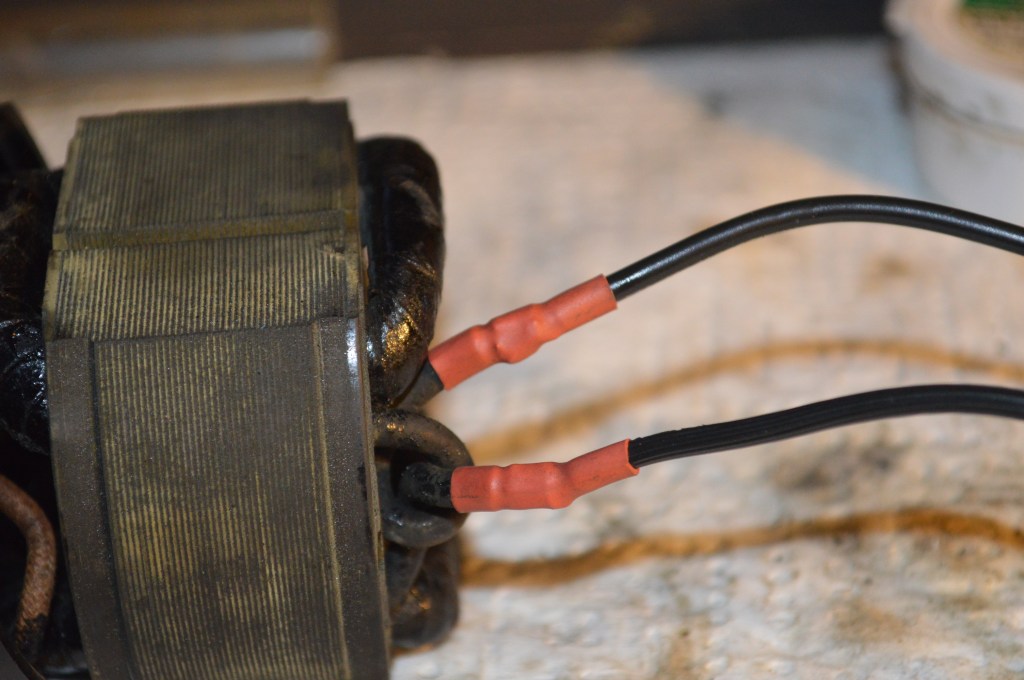

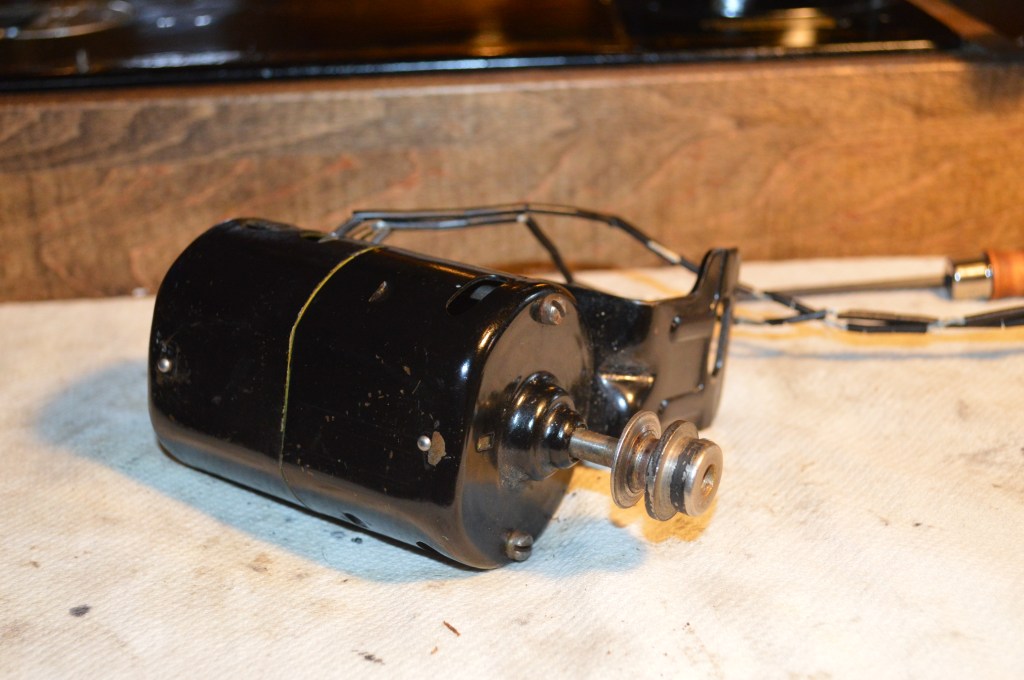

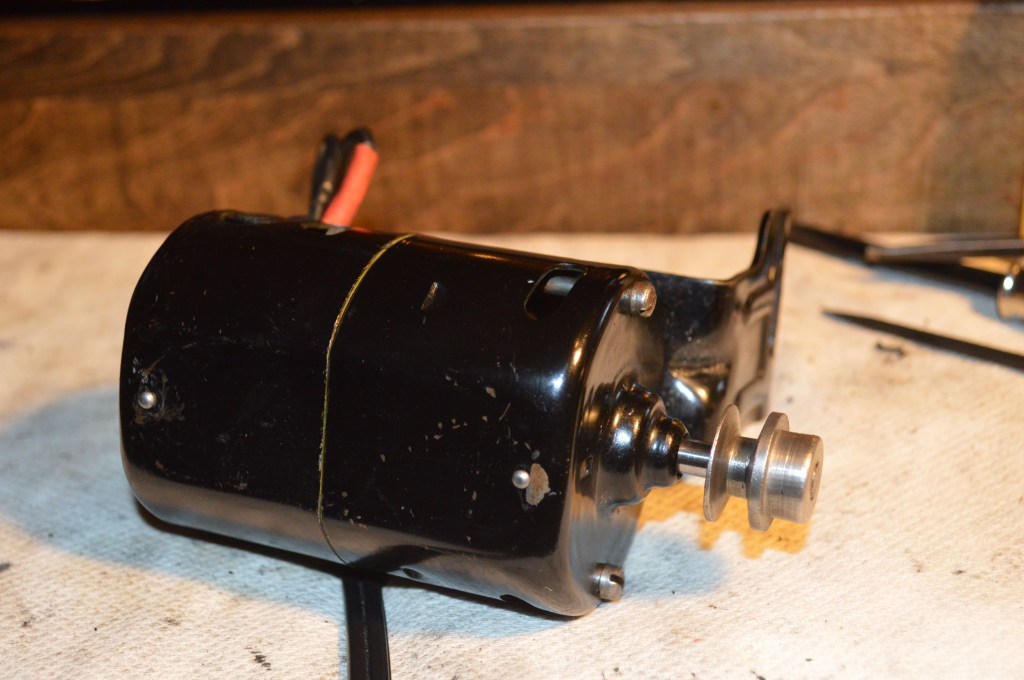

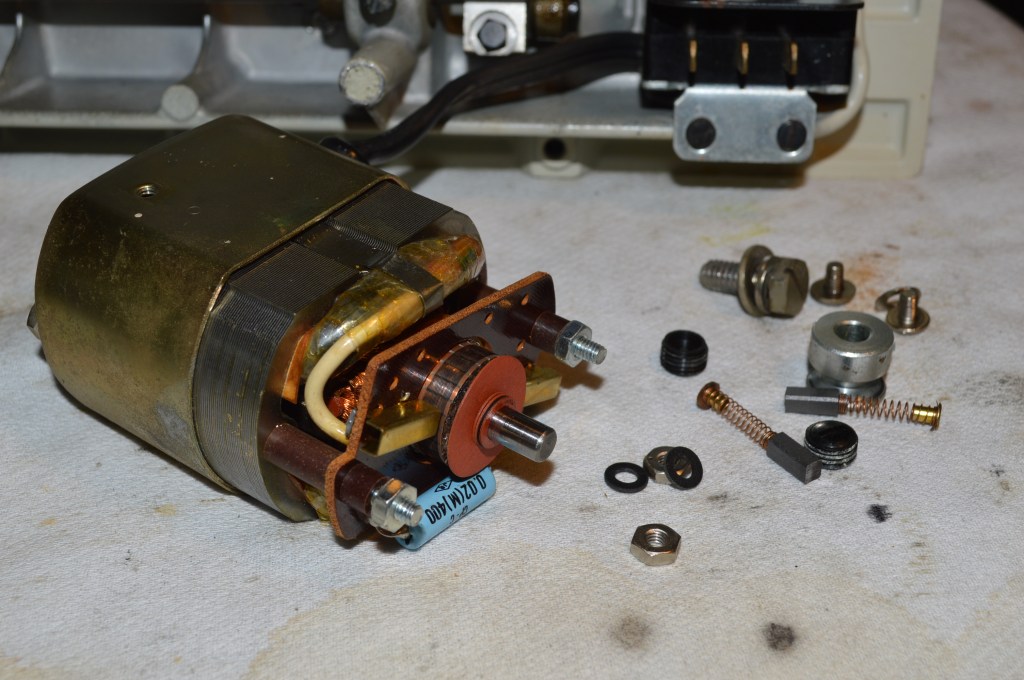

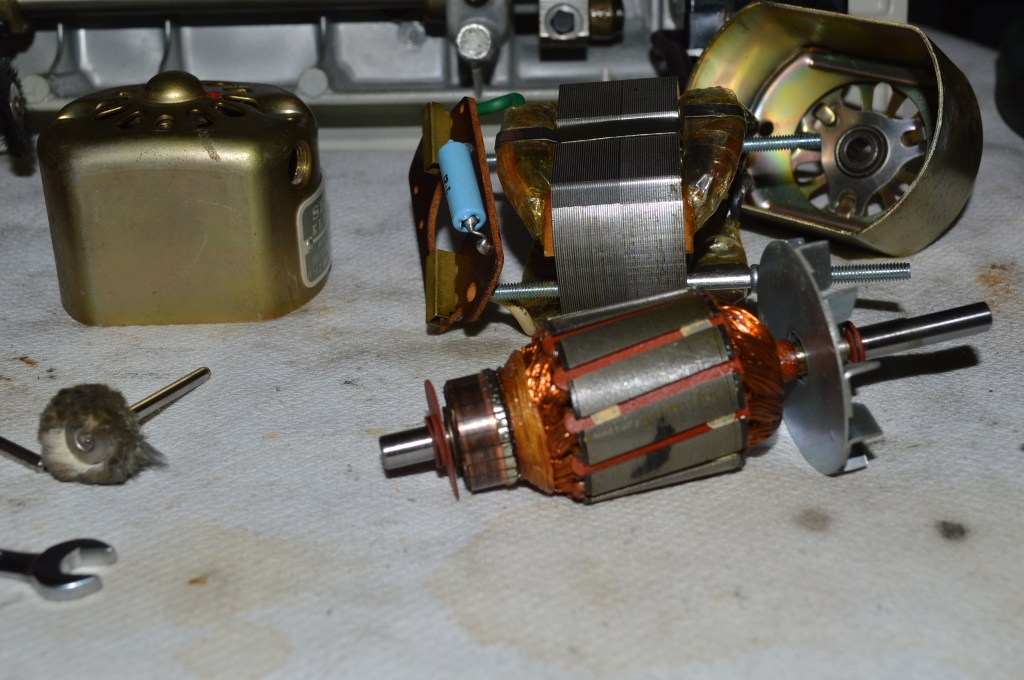

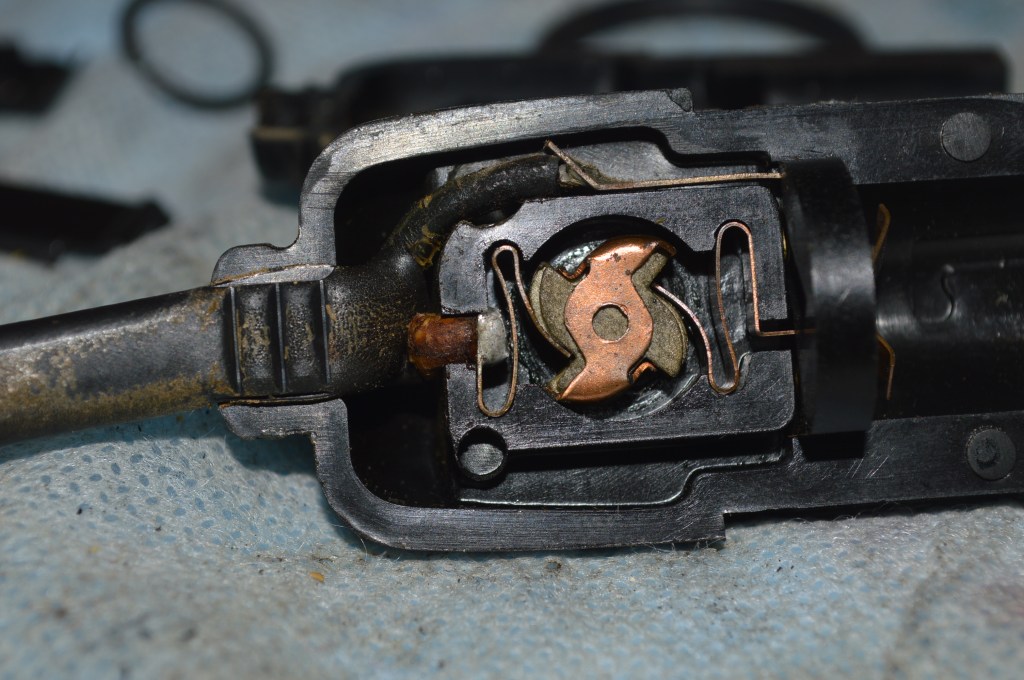

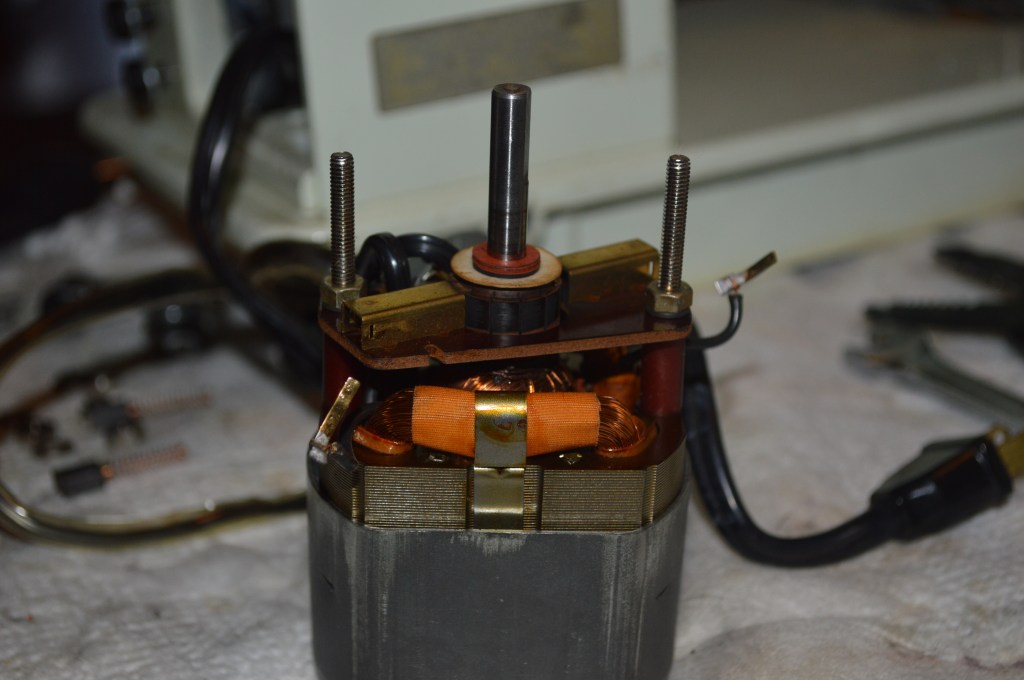

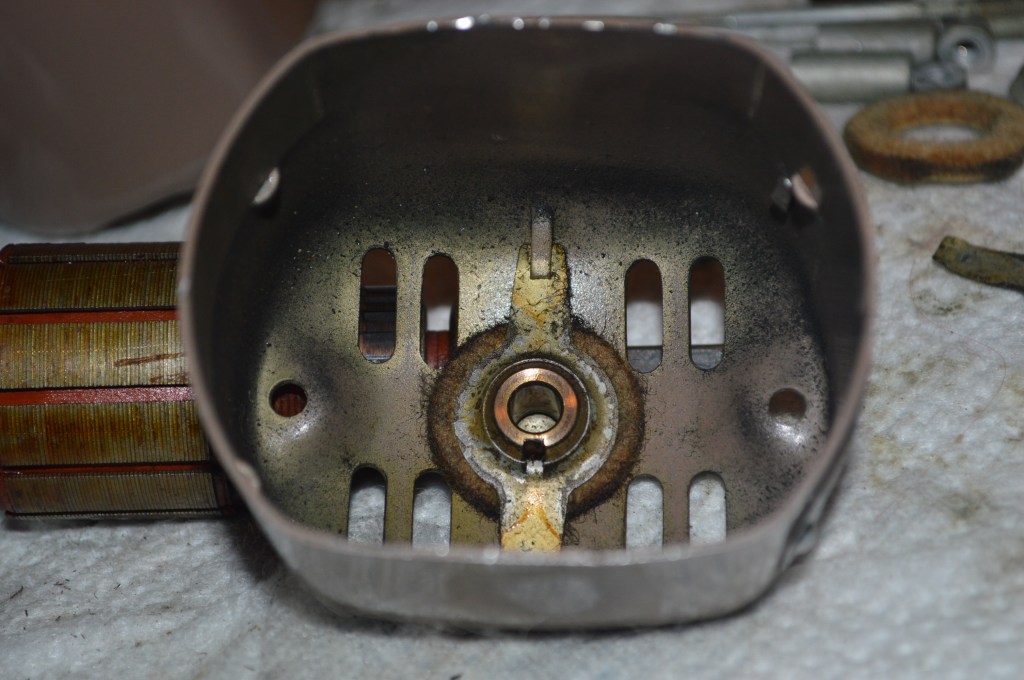

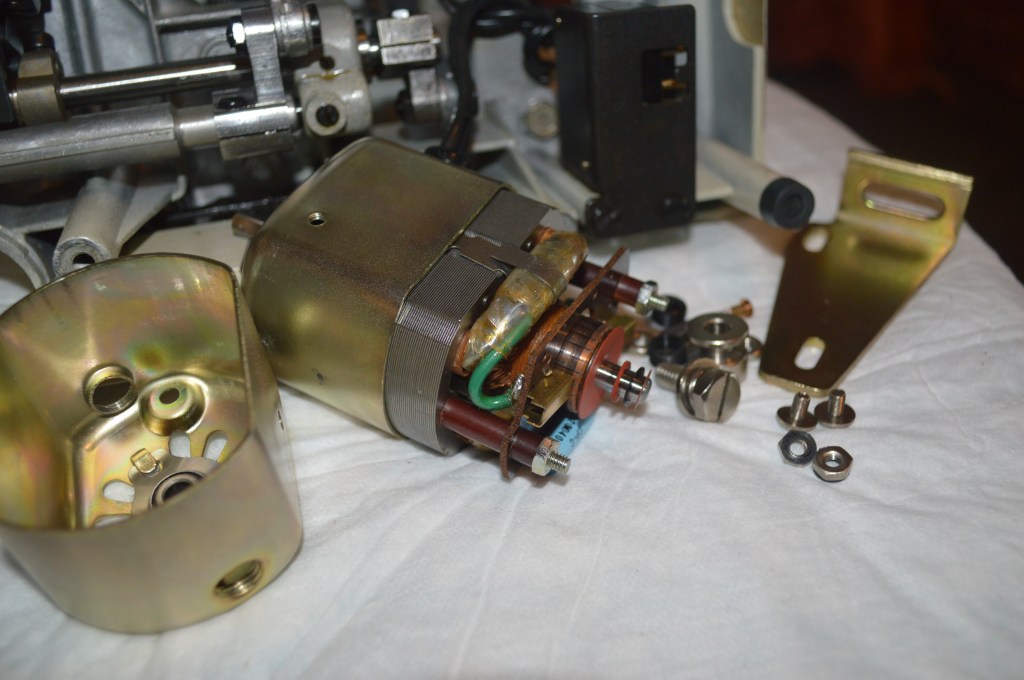

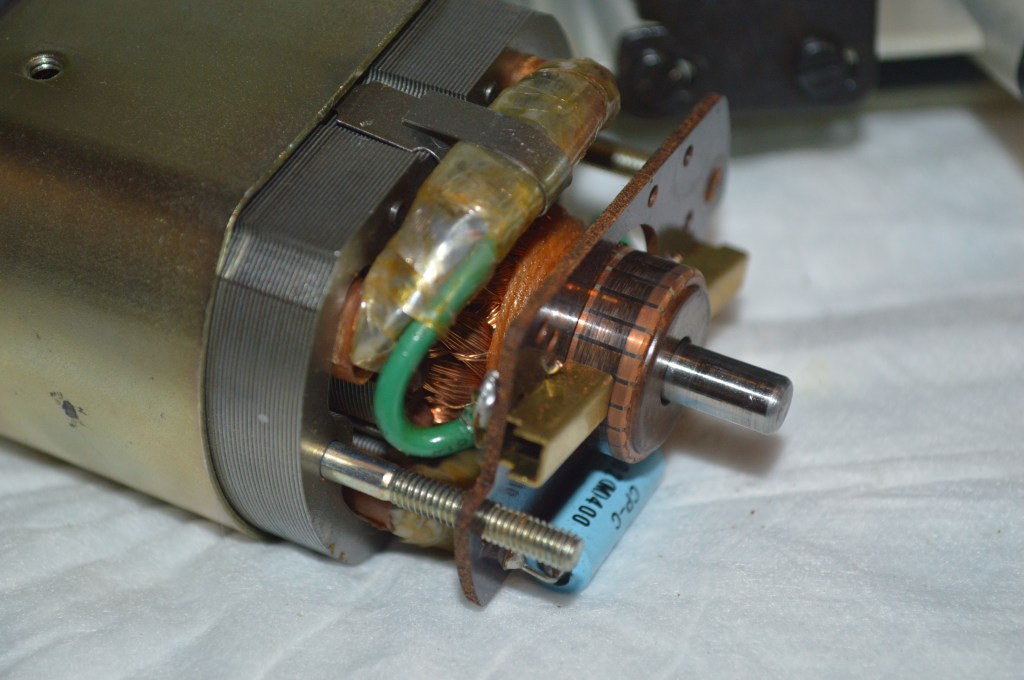

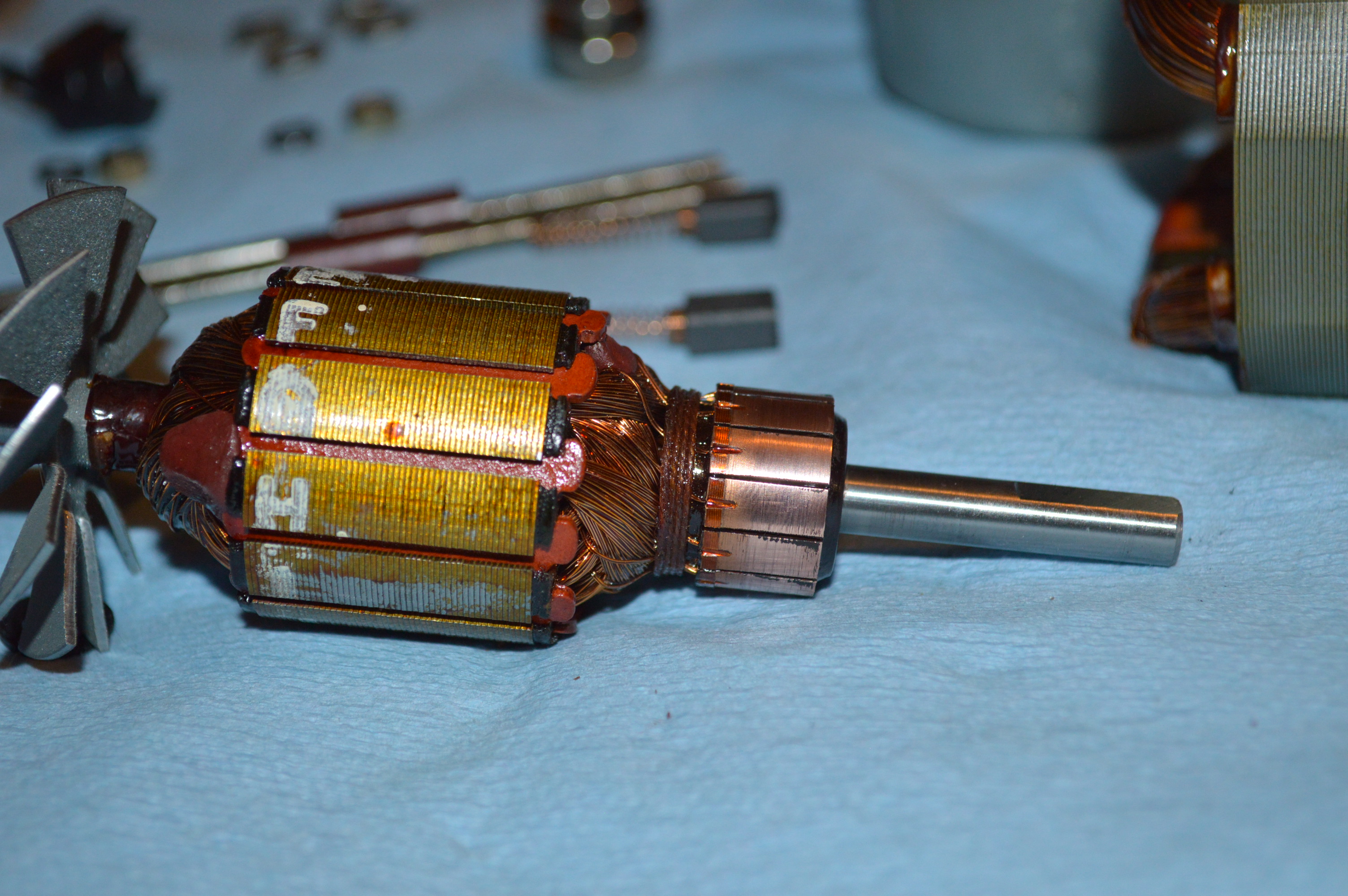

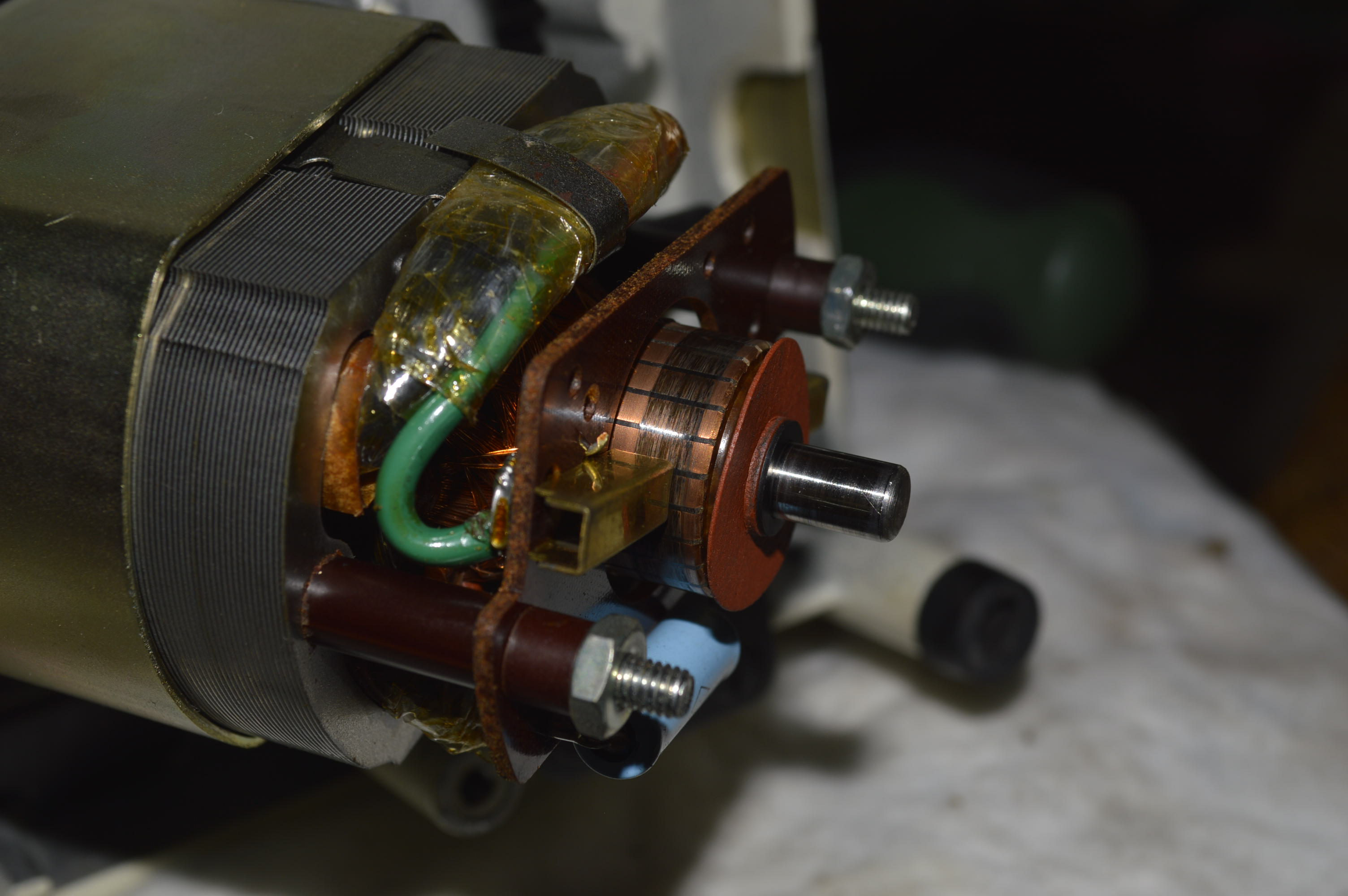

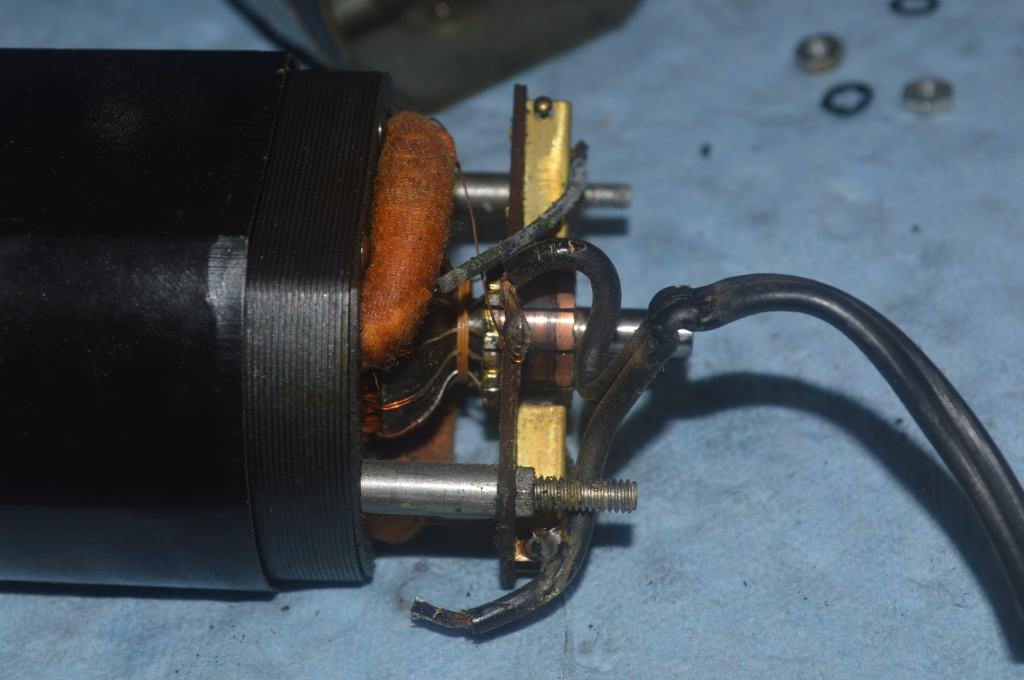

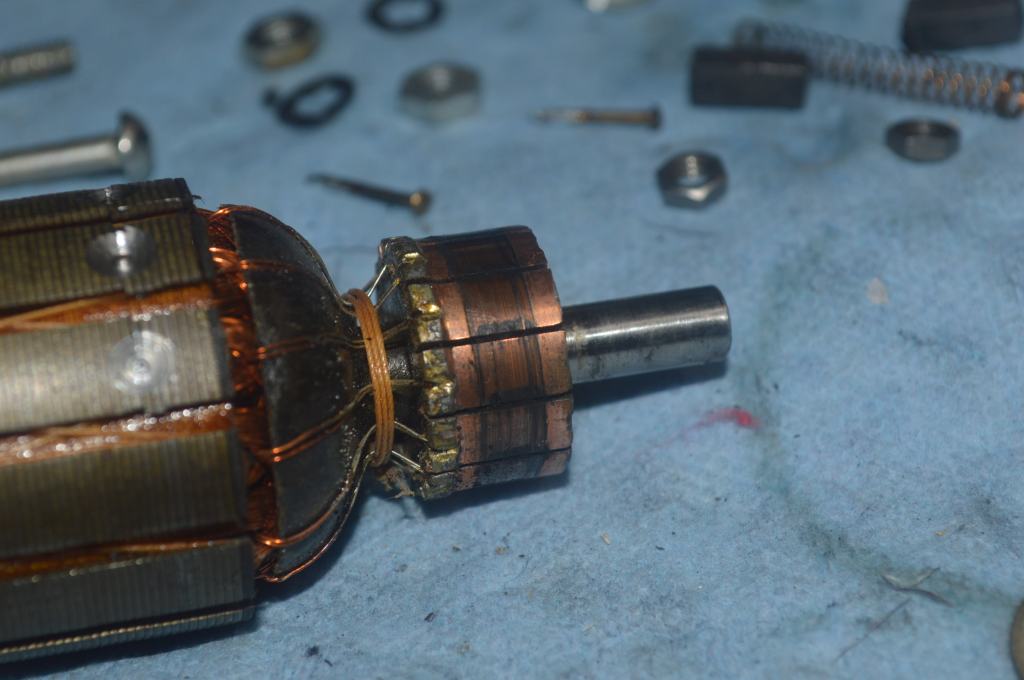

Now its time to restore the motor. The motor on the machine is a Morse motor and it is rated at 1.0 amps. This is a lot of power for a straight stitch machine. I don’t know the condition of the motor because I never run a motor before it is restored. I just feel it is better to do the restoration first. If there is an apparant problem (like shorted wires), I have a chance to see it before it burns up and ruins the motor. Always better safe than sorry!

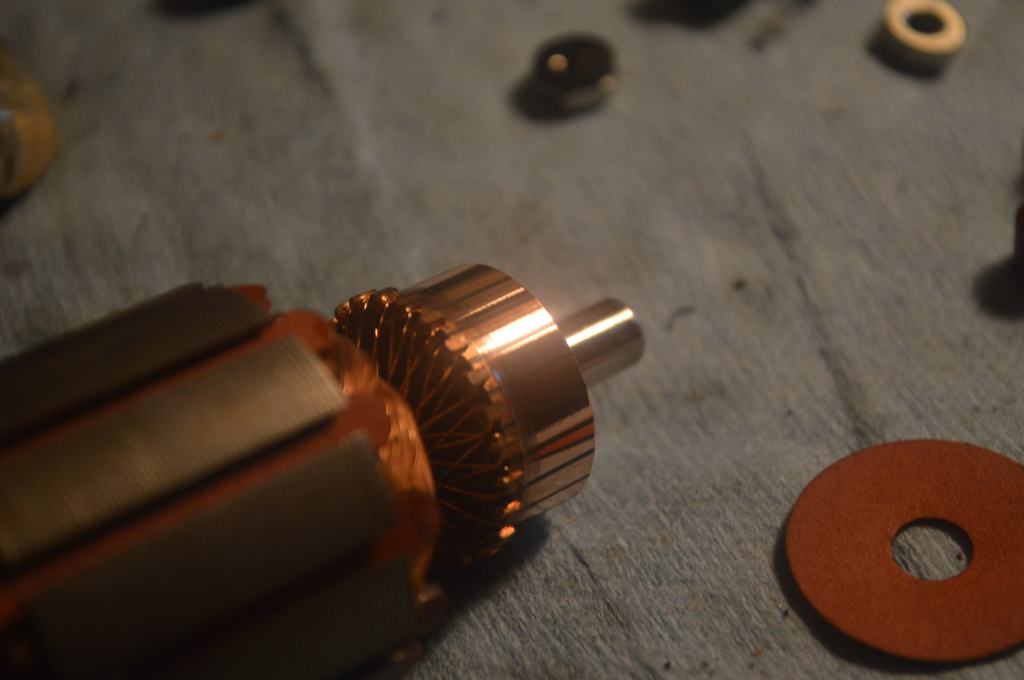

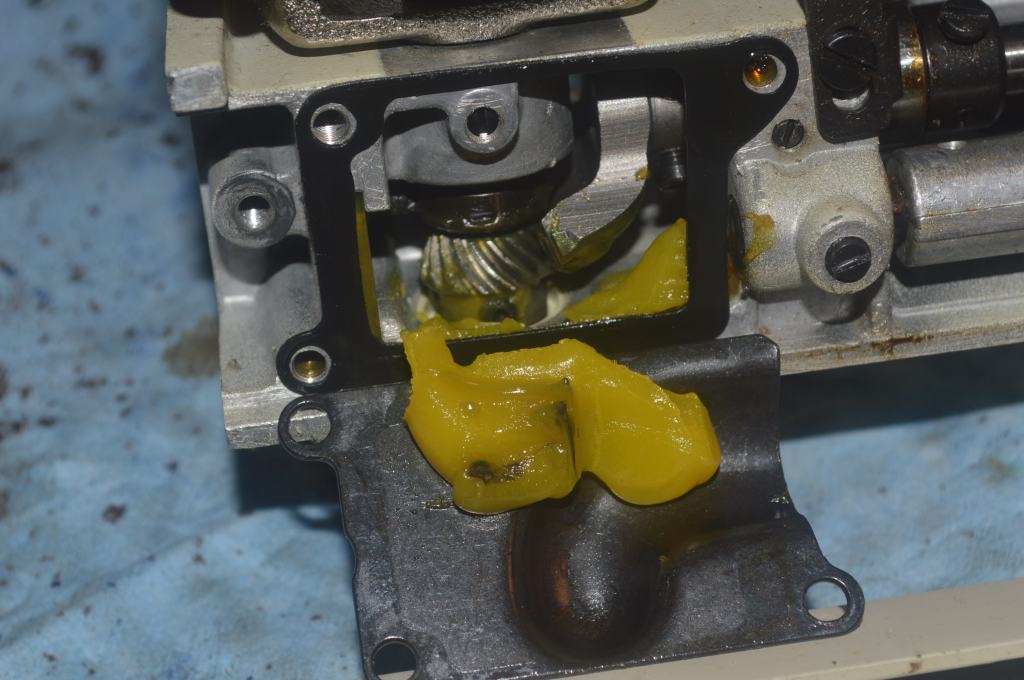

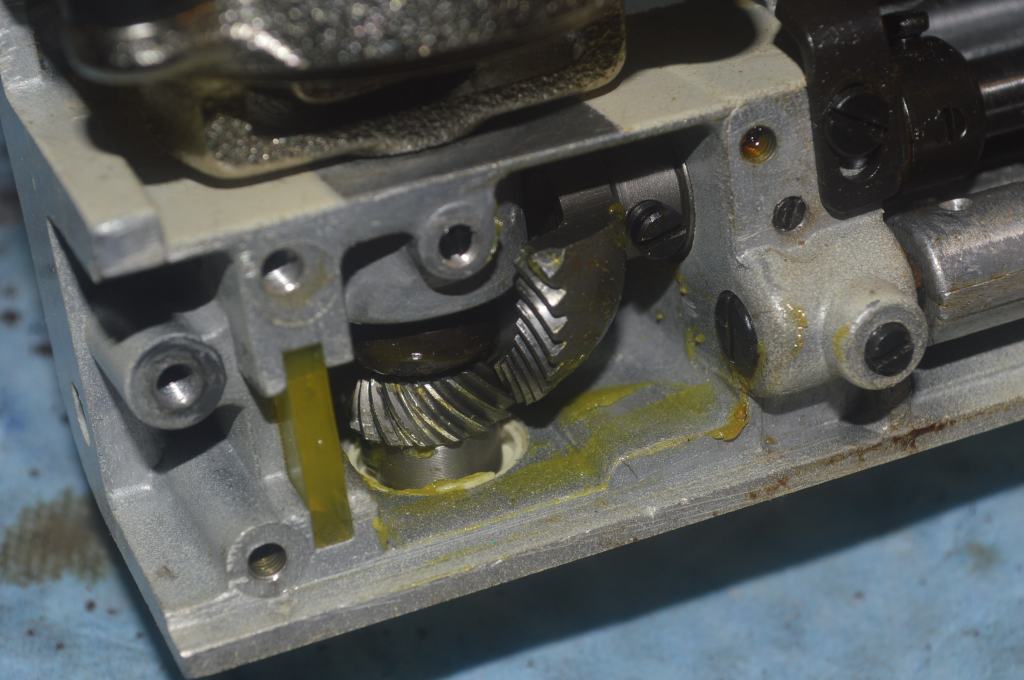

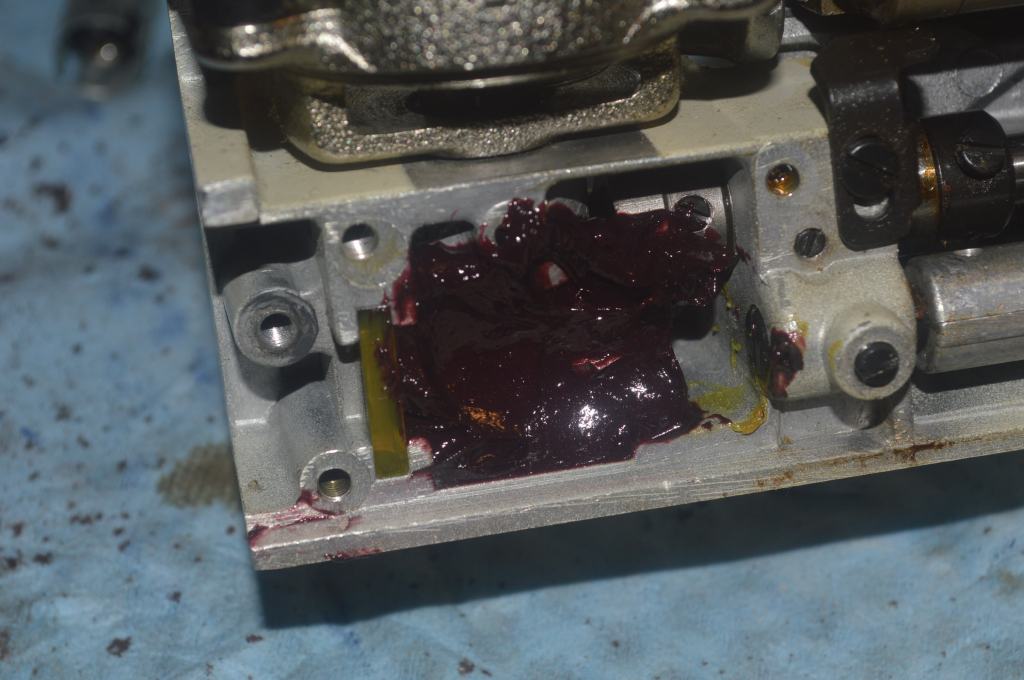

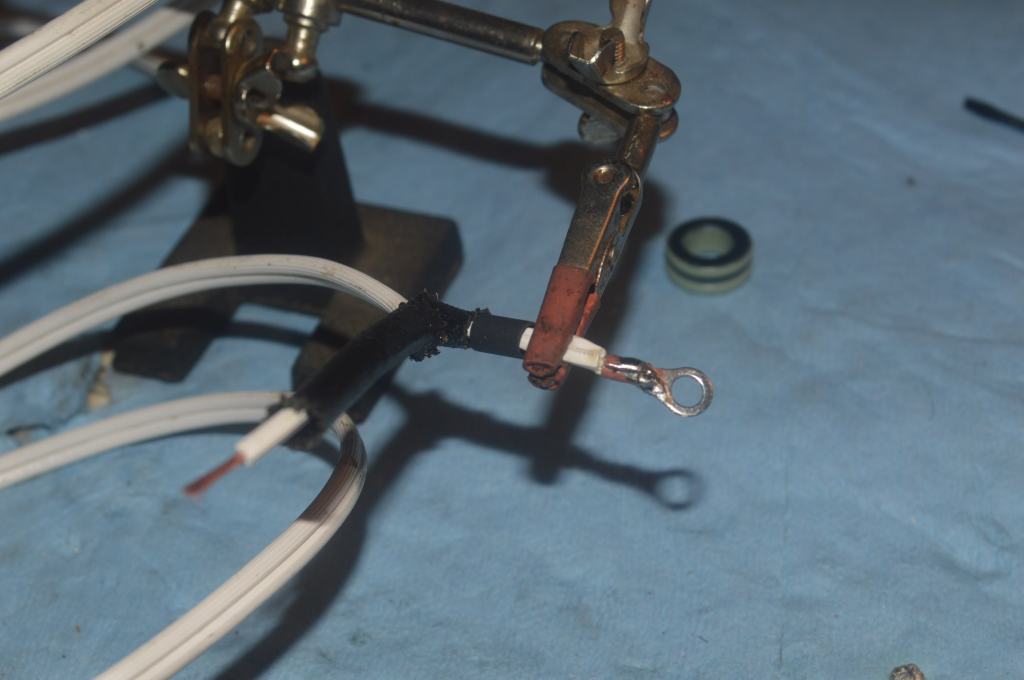

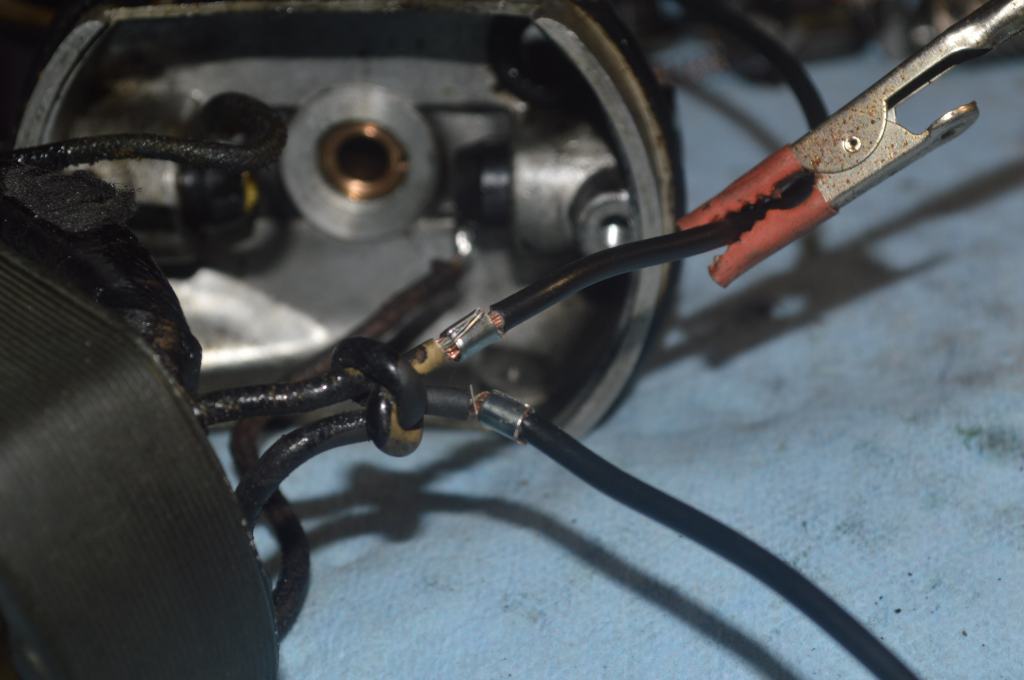

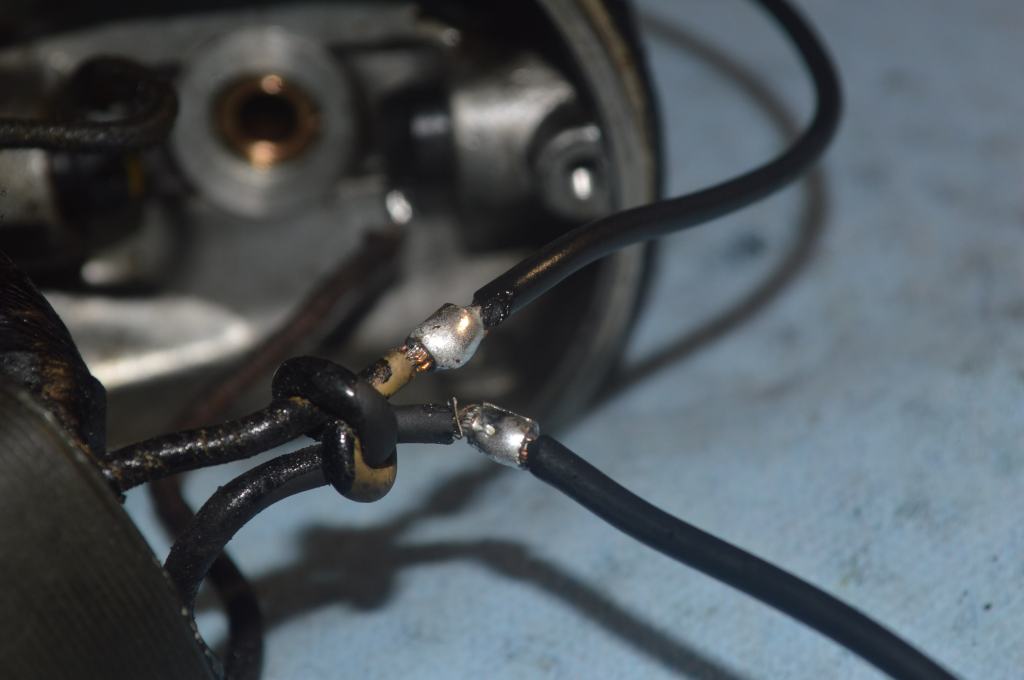

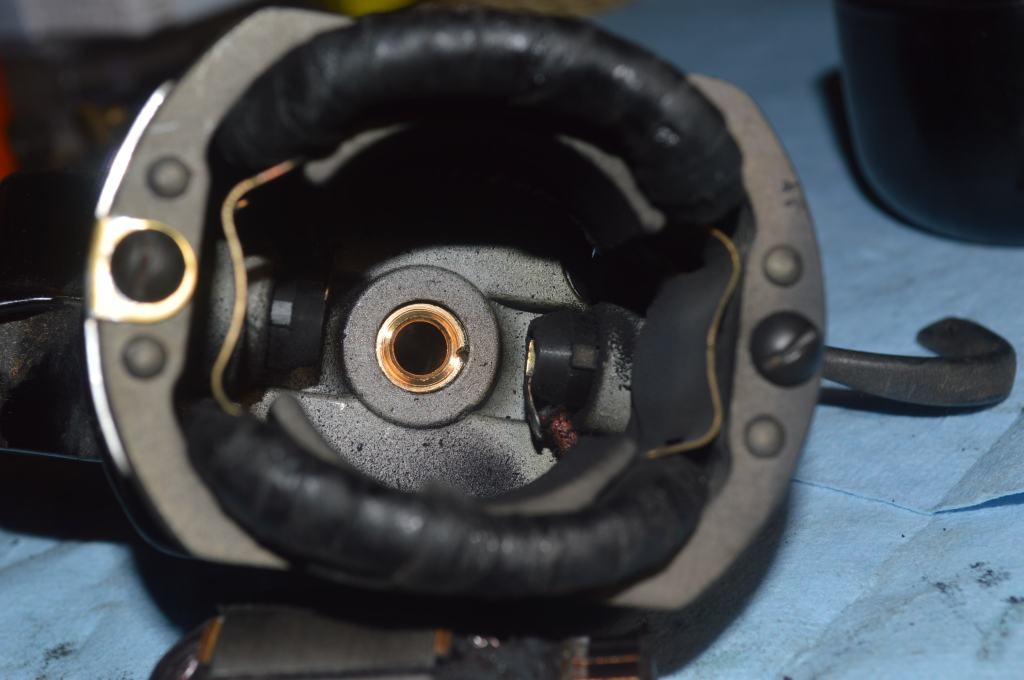

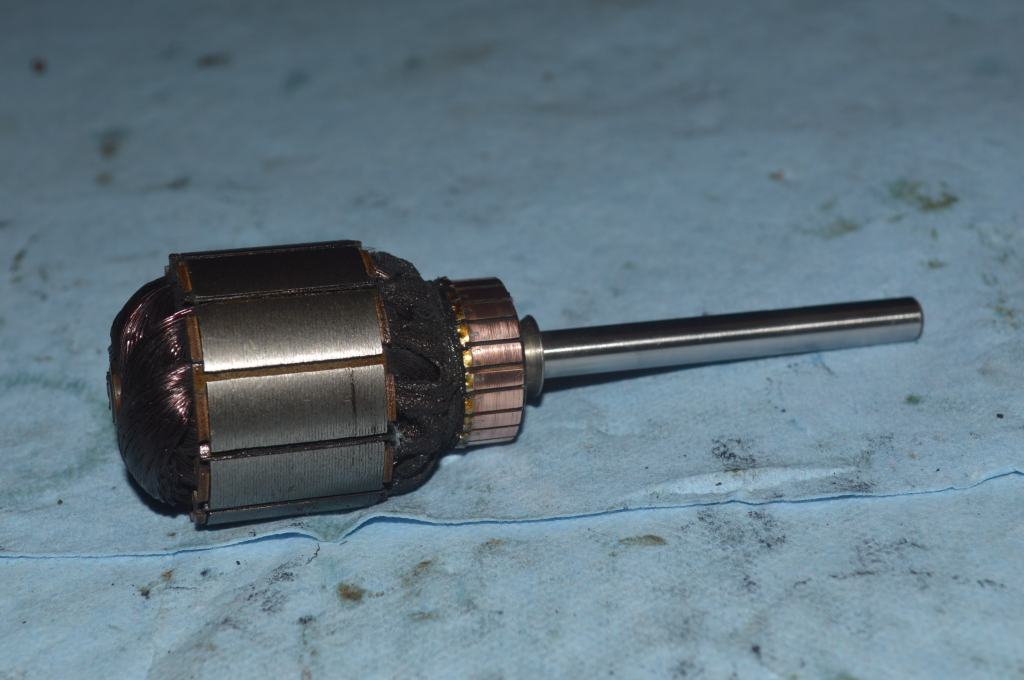

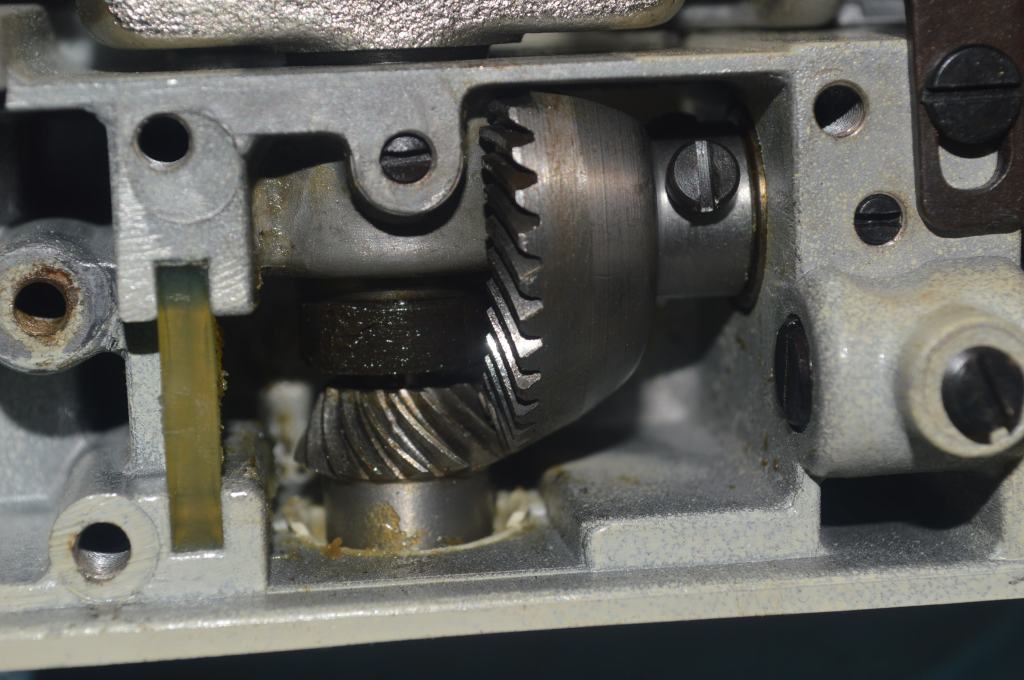

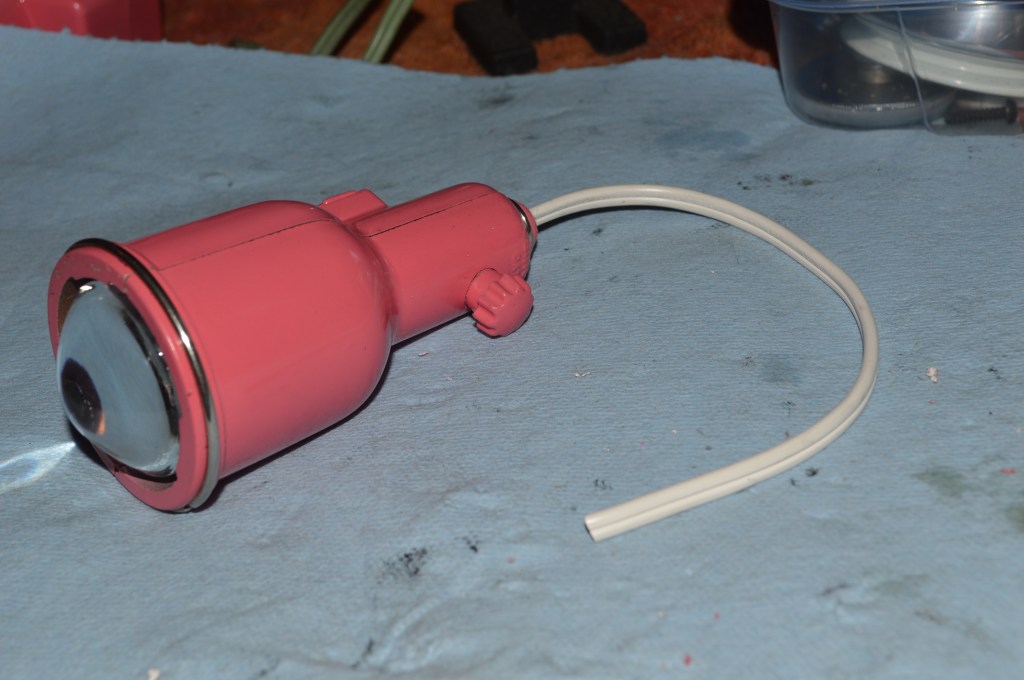

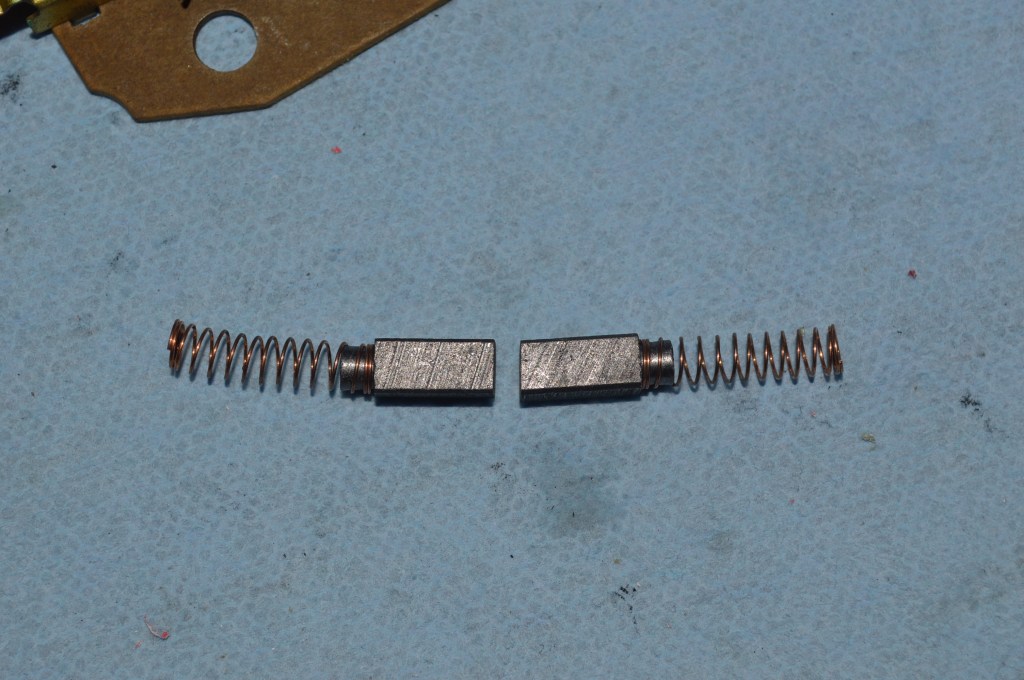

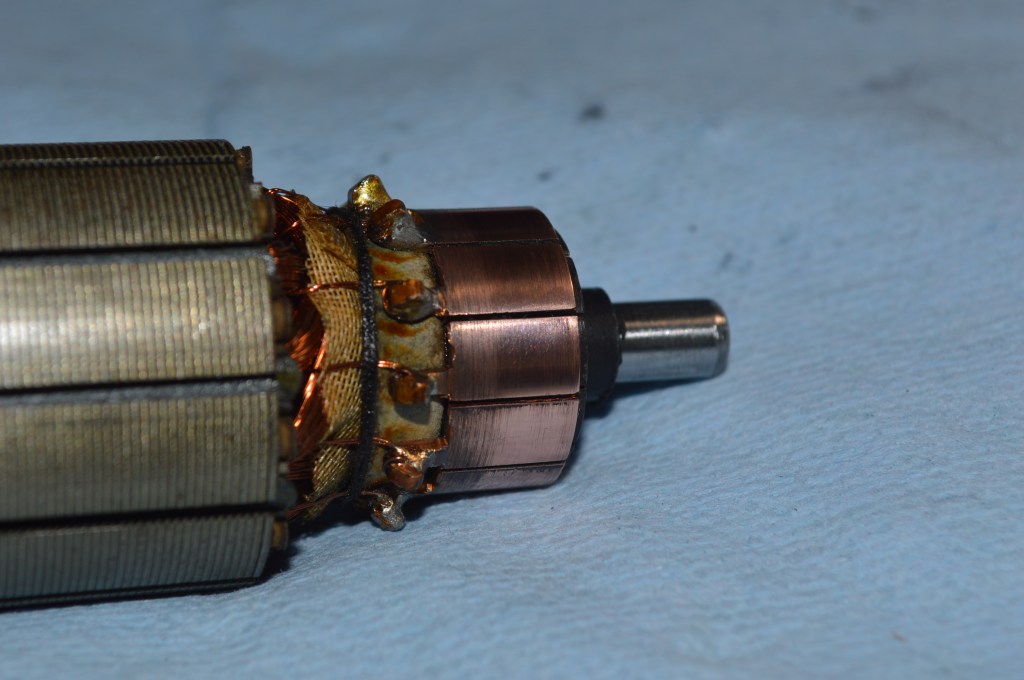

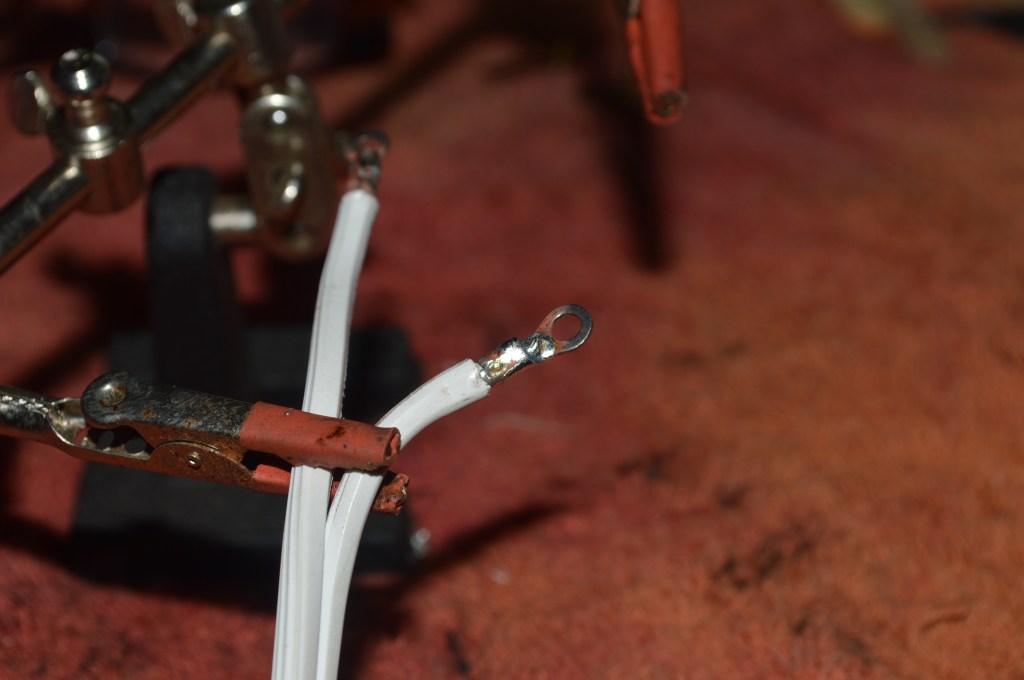

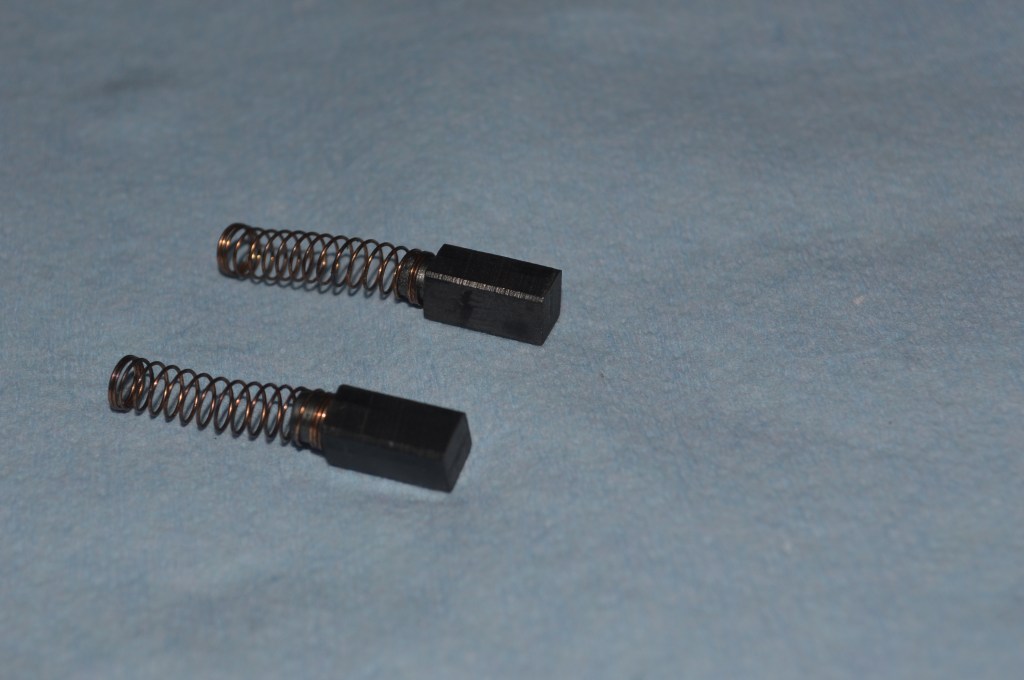

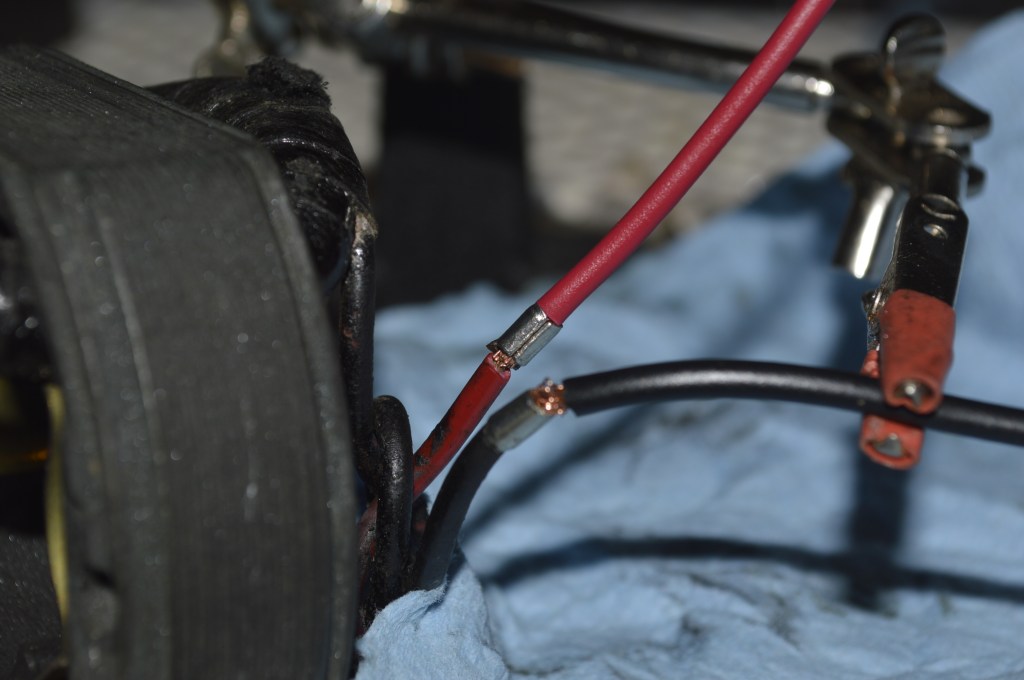

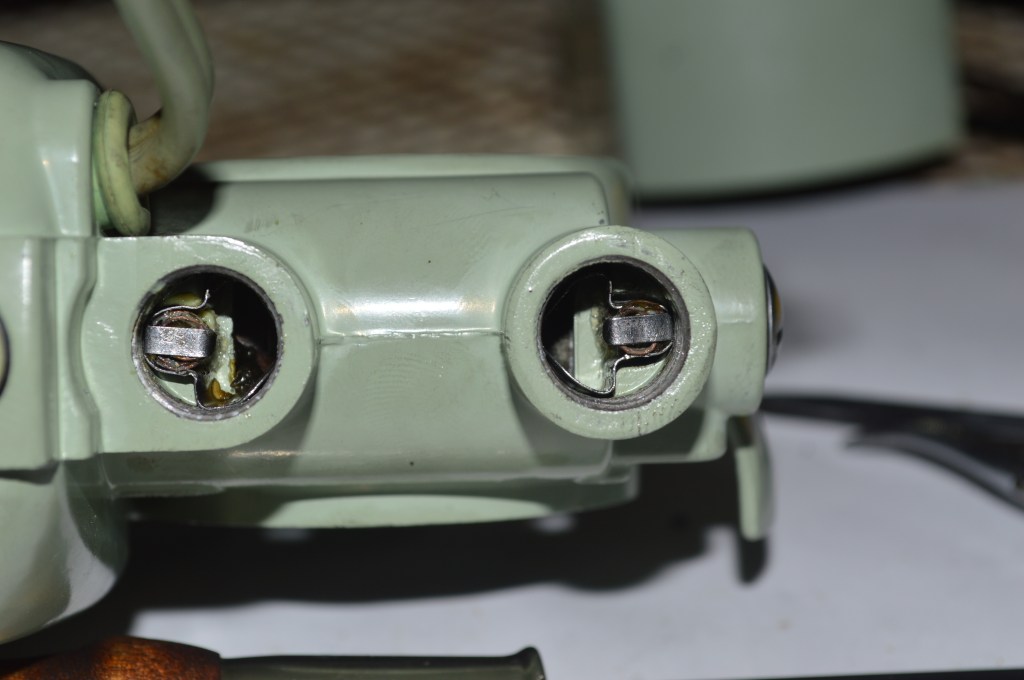

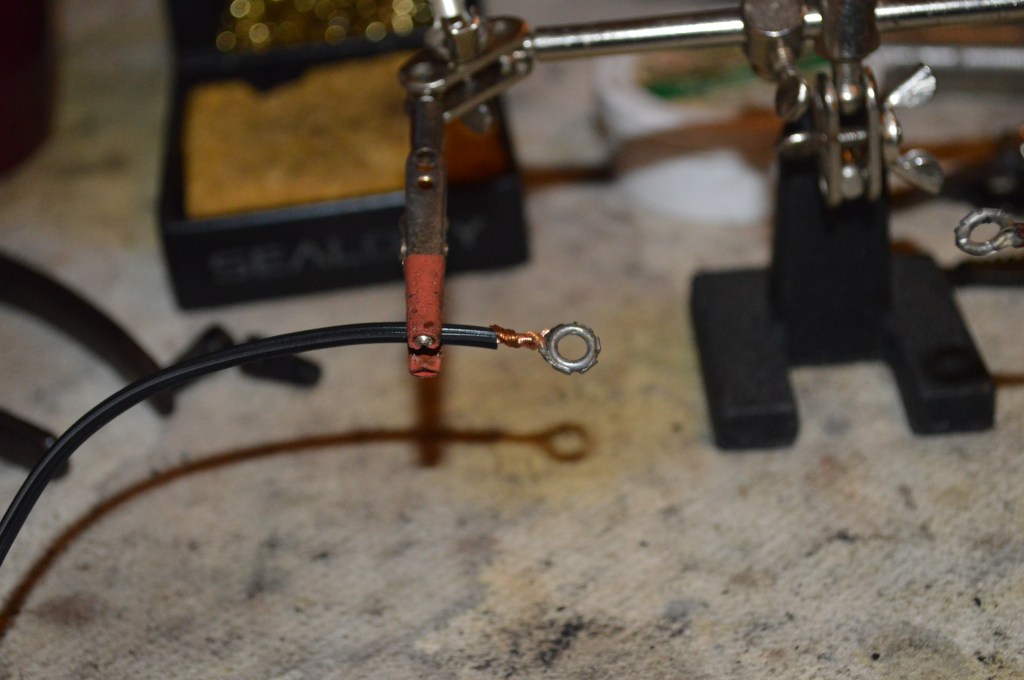

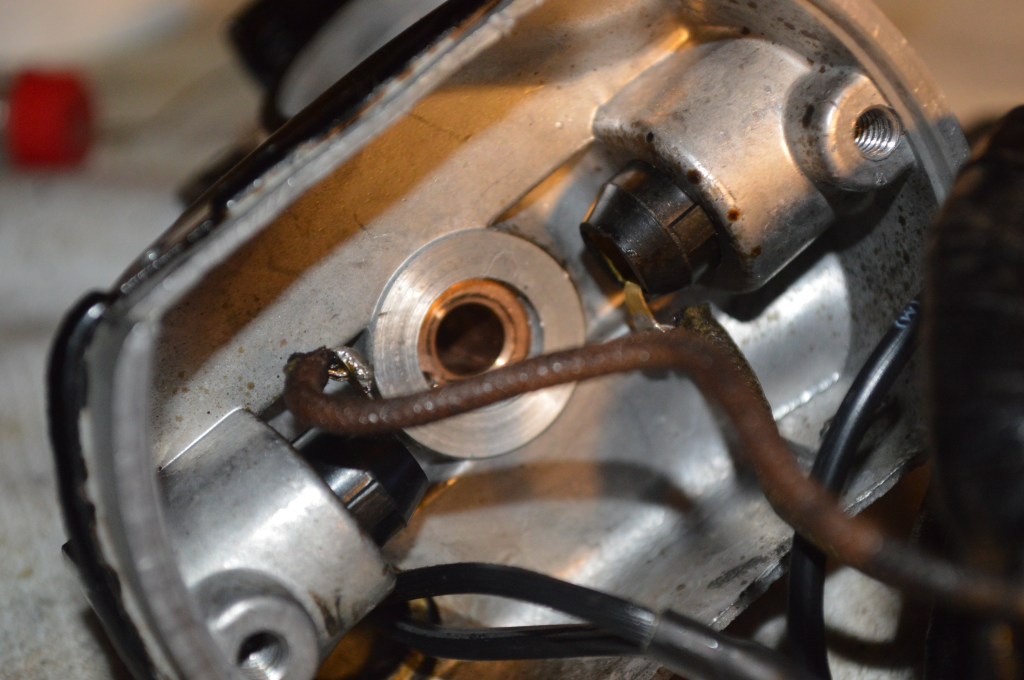

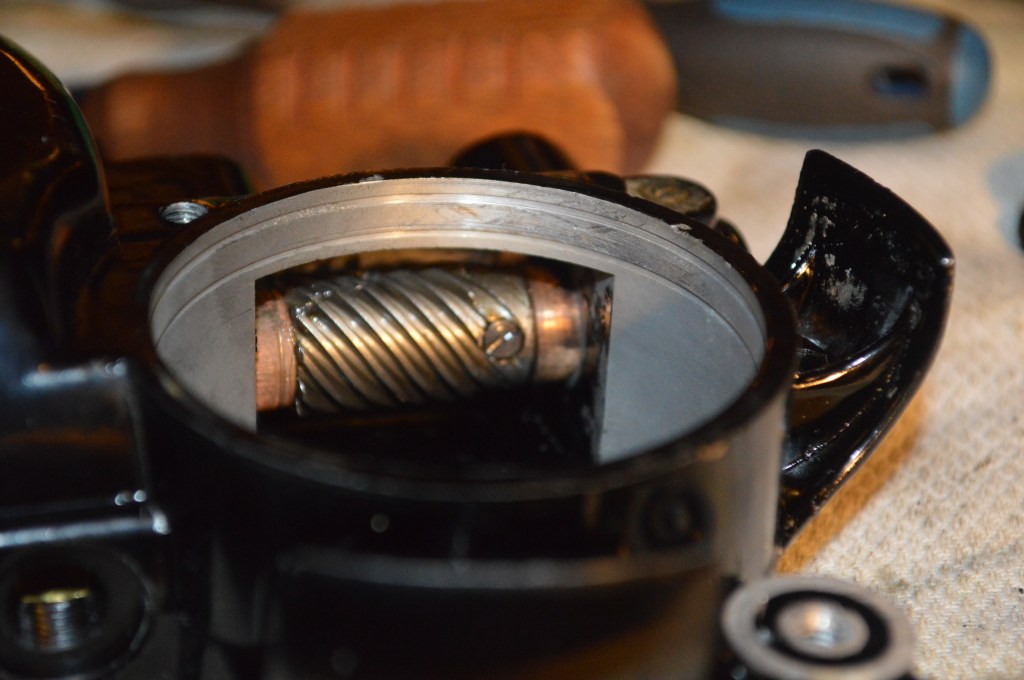

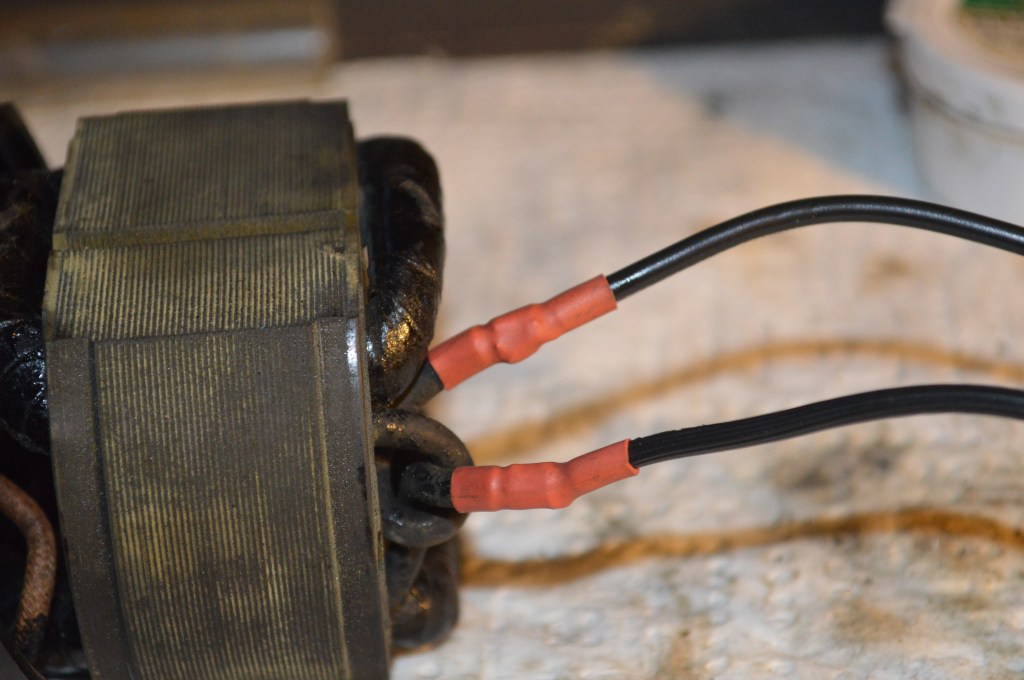

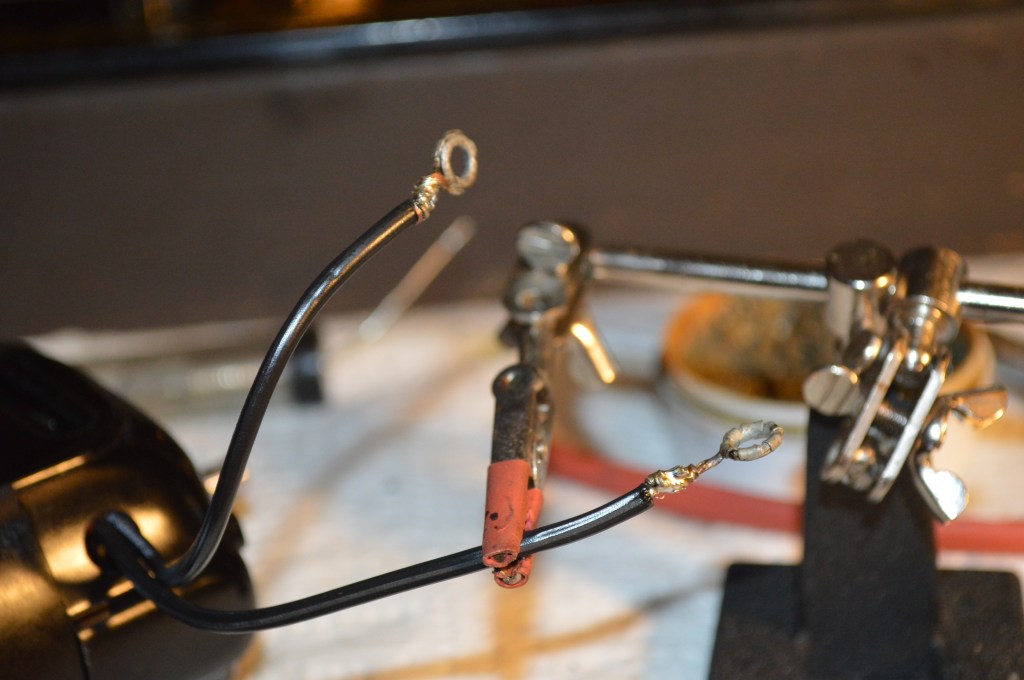

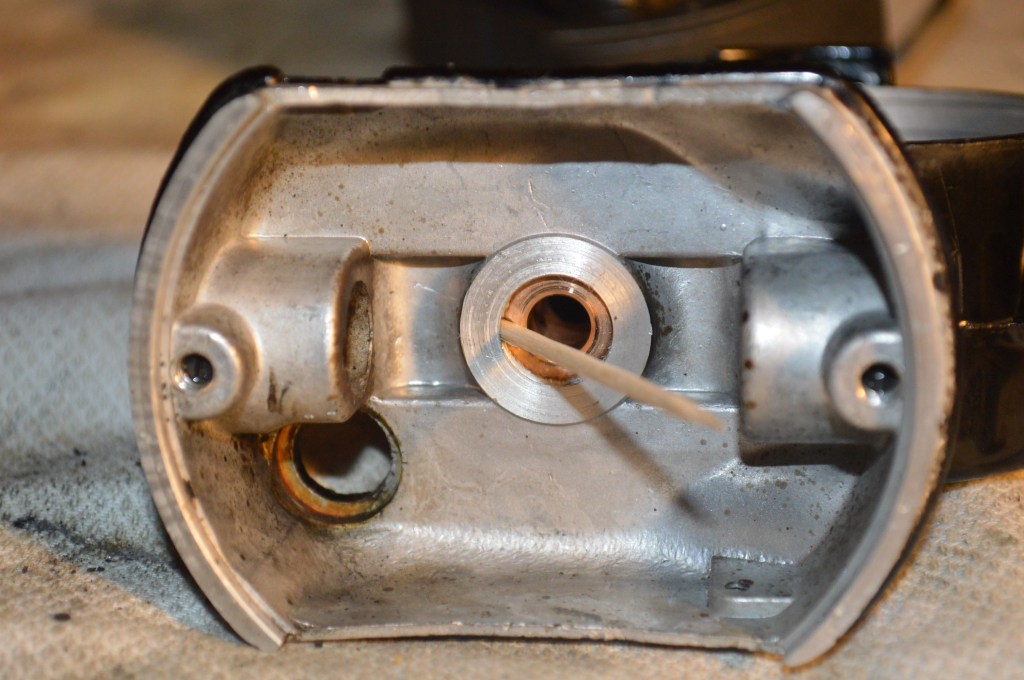

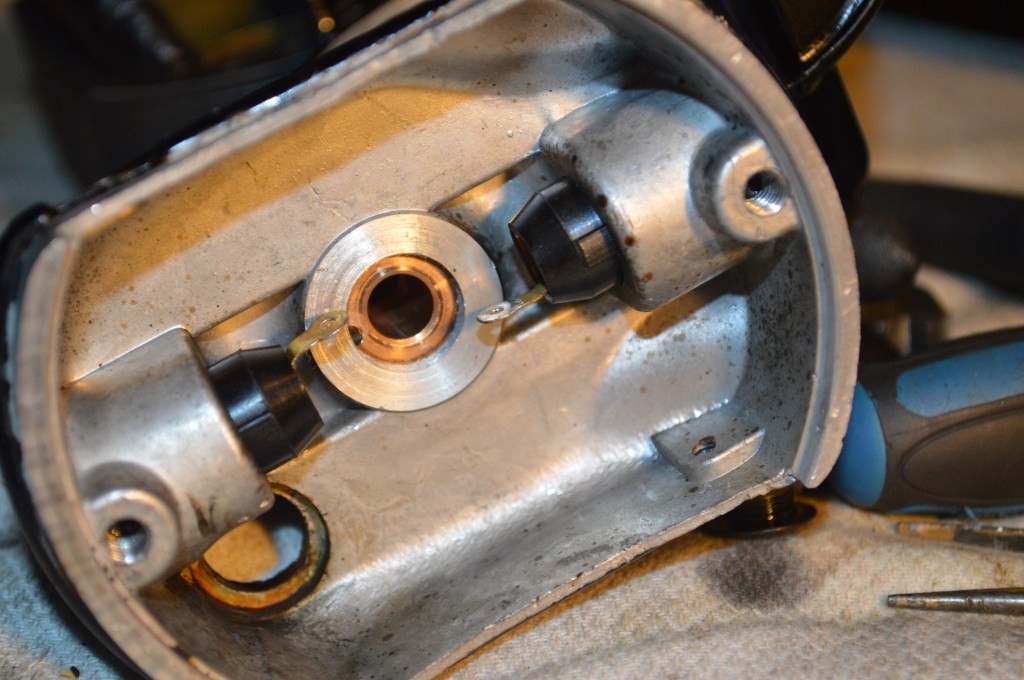

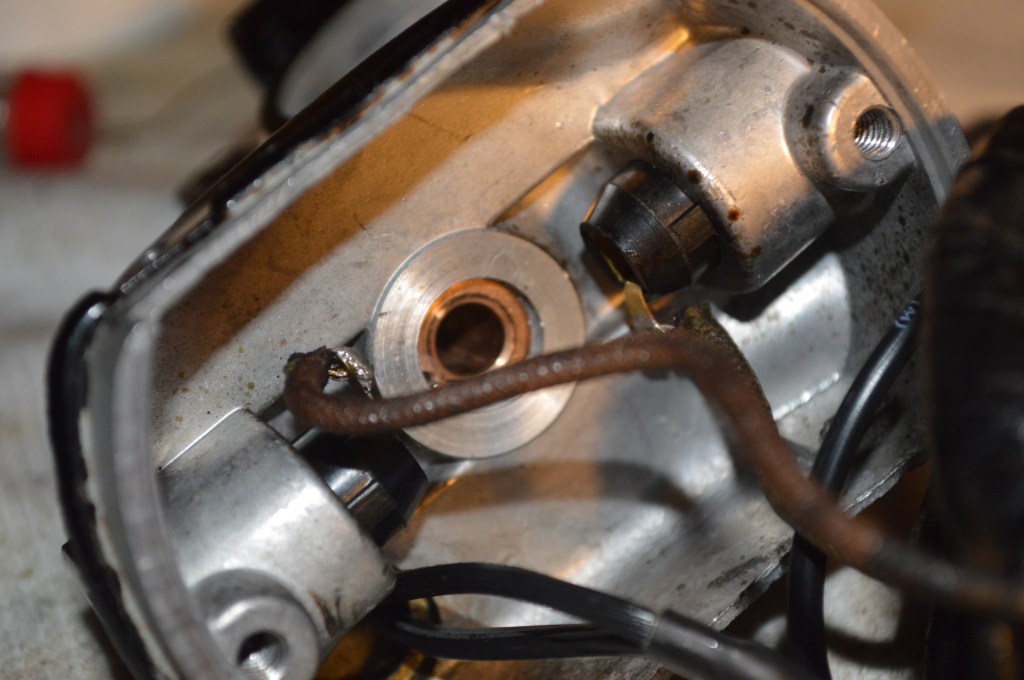

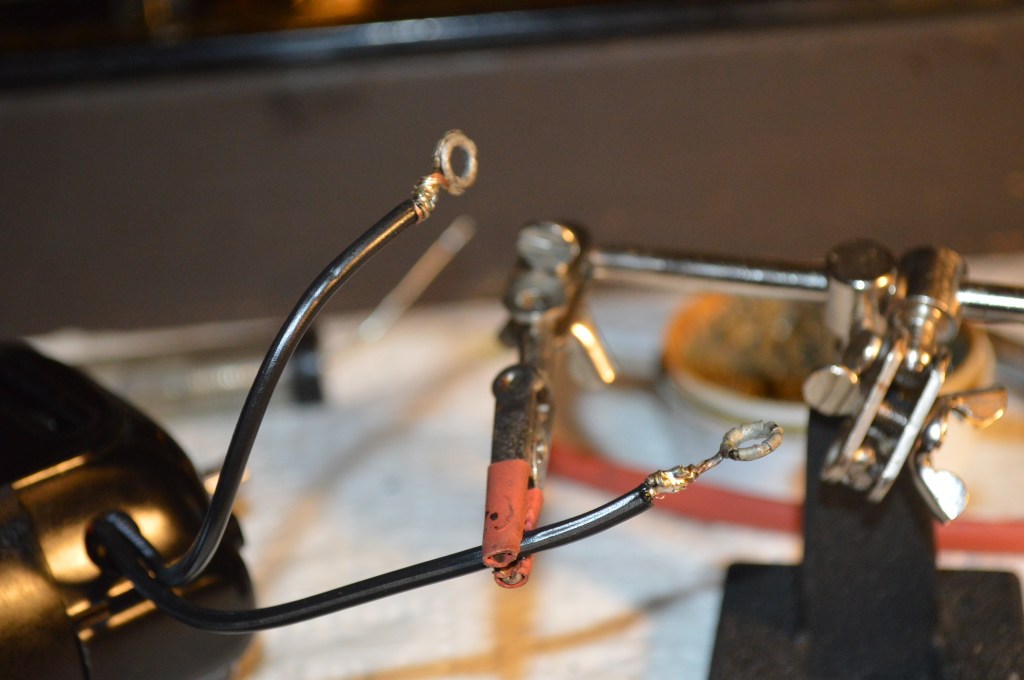

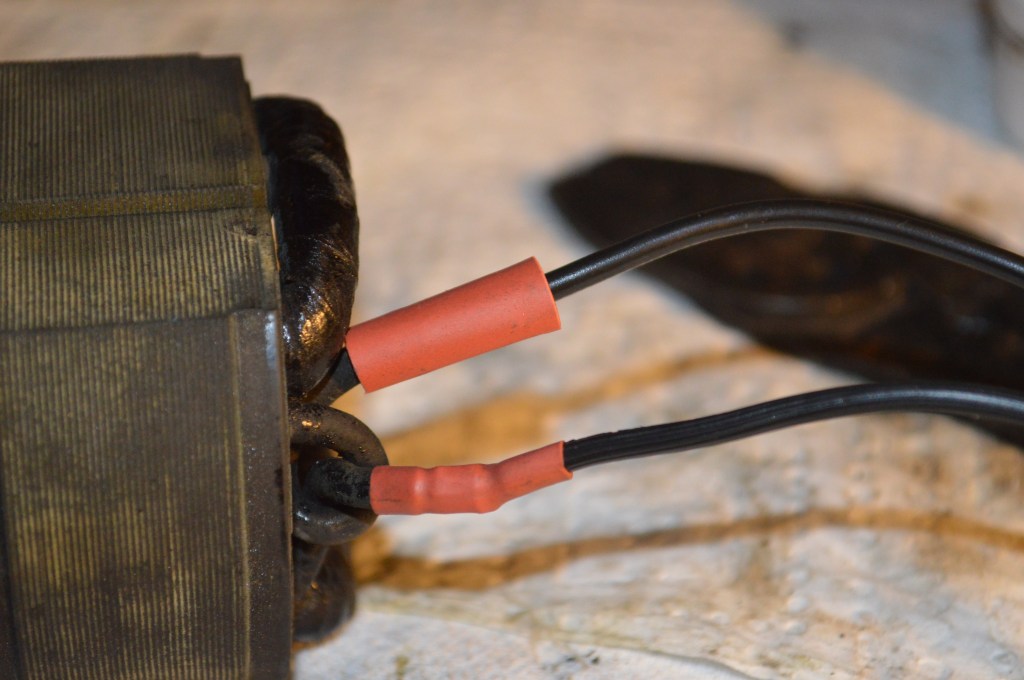

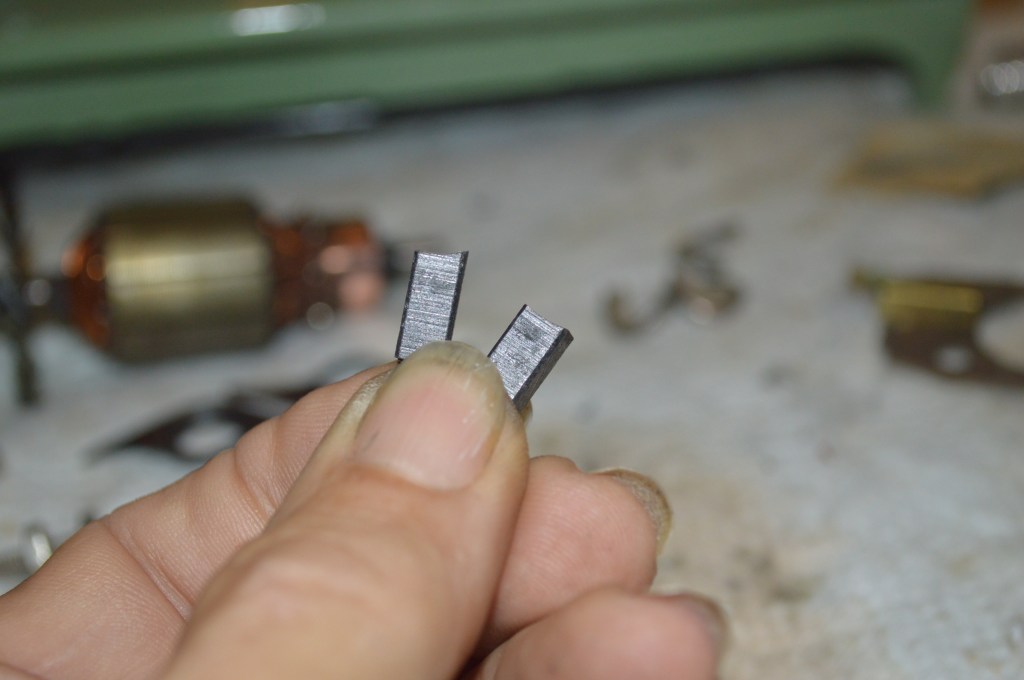

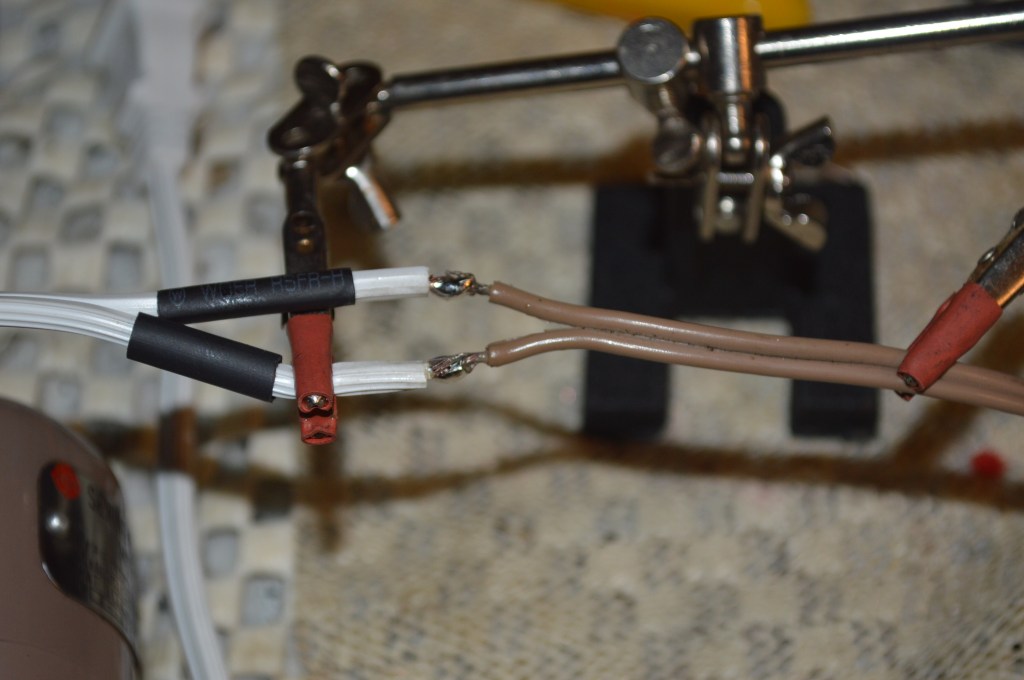

Before reassembly, the brushes are removed and cleaned, the armature and shafts are polished, the motor housings are cleaned on the inside and the oil wicks are recharged. The main wires are attached and soldered to the brush tubes. After reassembly, paint chips on the motor housing are corrected with paint match paint.

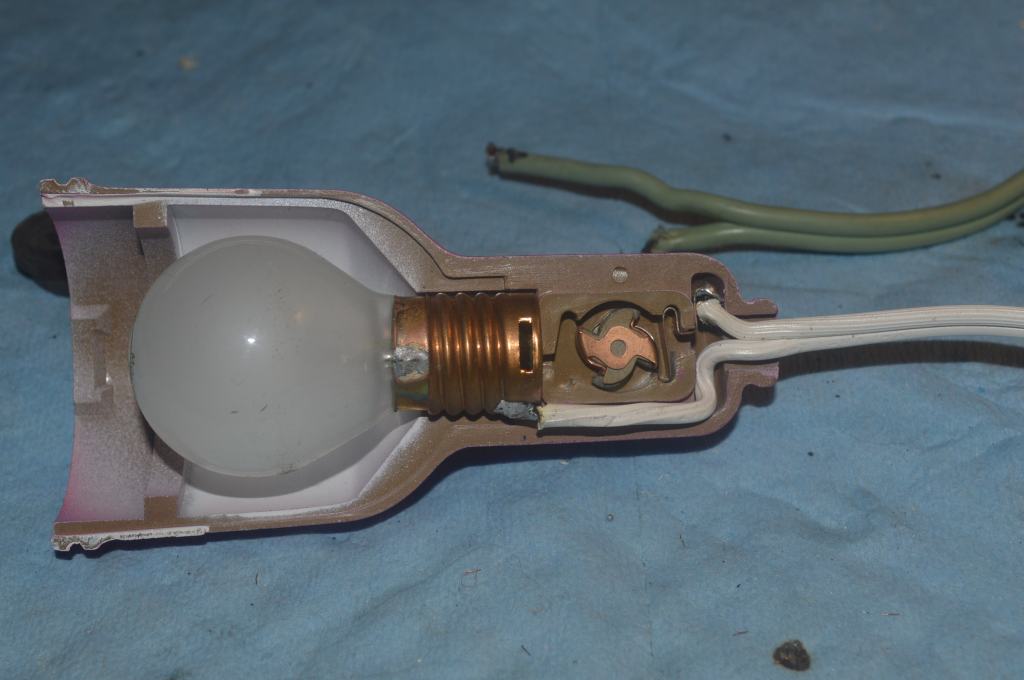

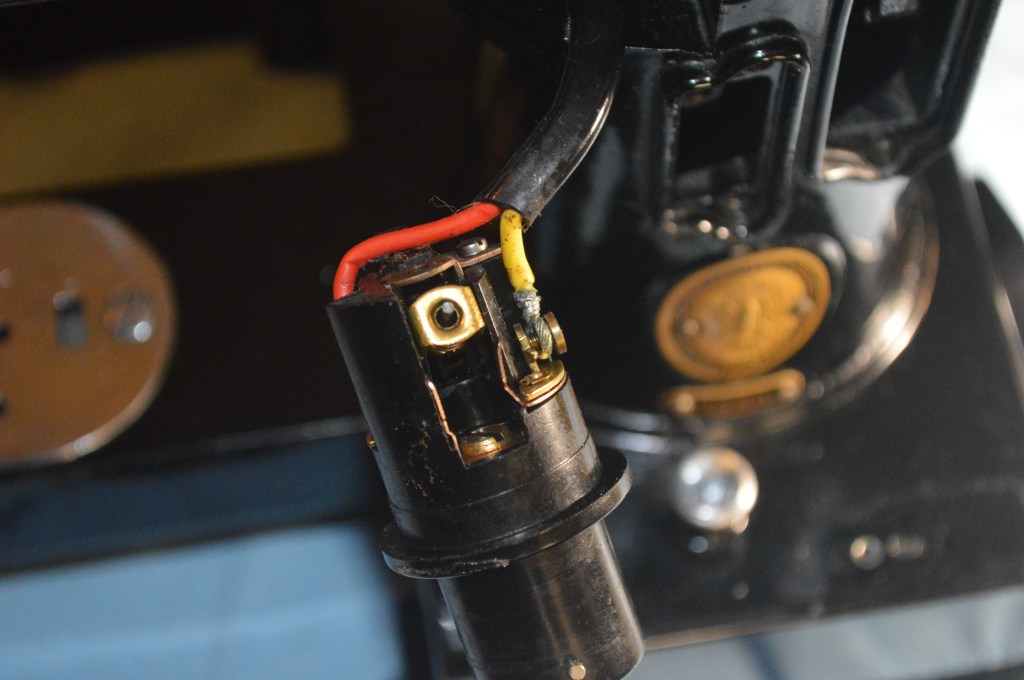

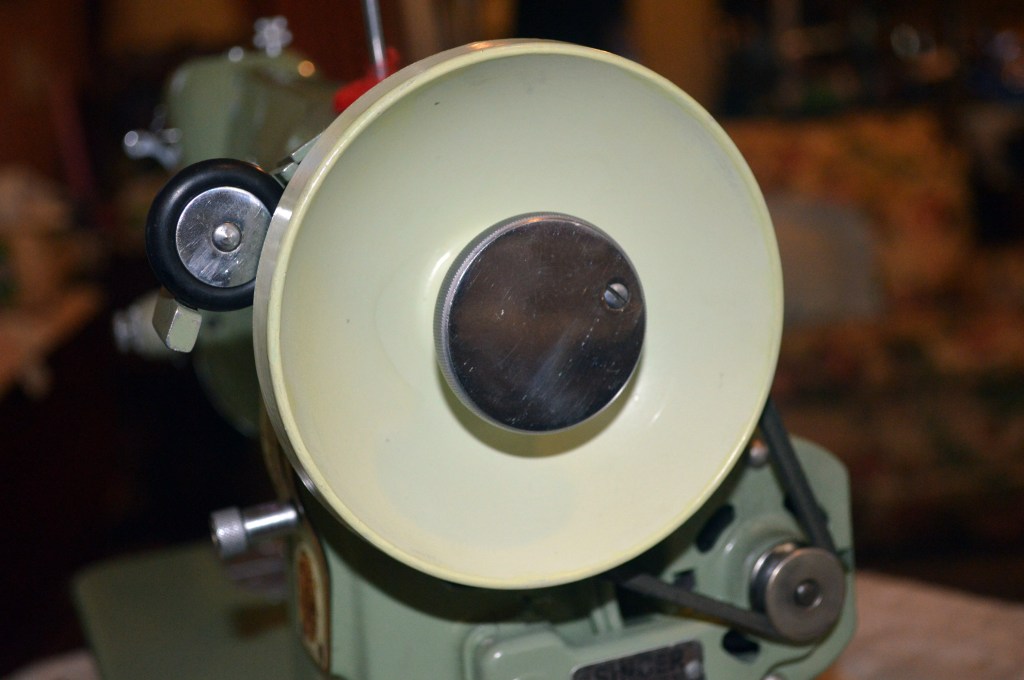

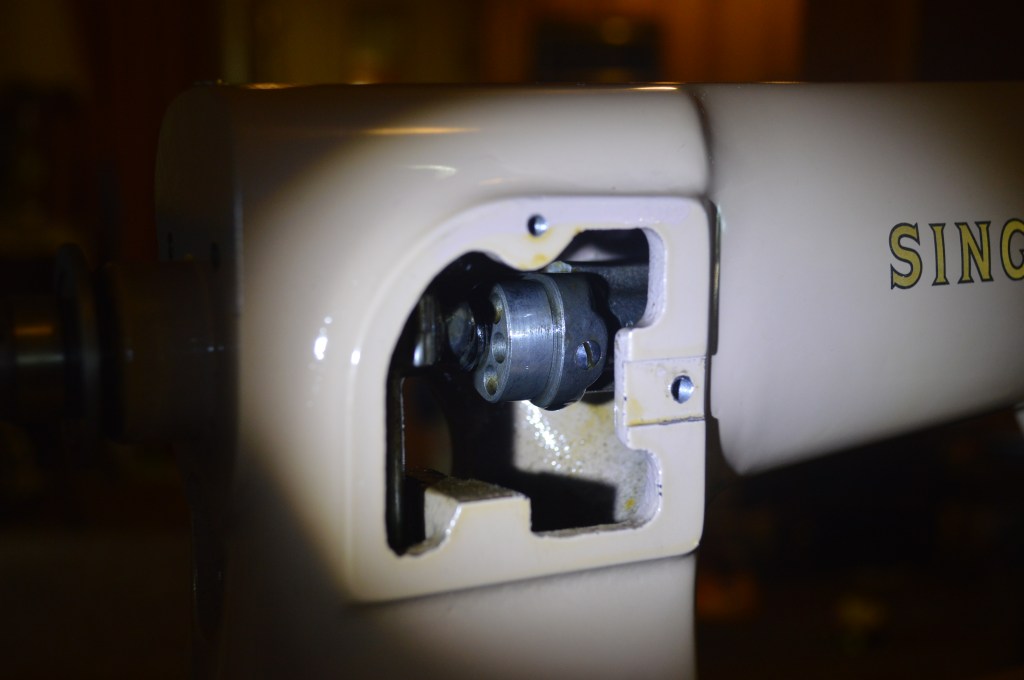

Next, the light fixture is restored. This machine has an aftermarket light attachment that is very likely the same (or slightly later) vintage as the machine. The wires need to be replaced, and I think I can improve the cosmetic appearance by polishing the light shroud.

Except for reassembly, the only steps left are polishing all of the chrome plated pieces.

Before polishing, they are cleaned. Because taking picture of shiny parts is so difficult, They will present themselves in the final pictures… until then, just remember how they look now!

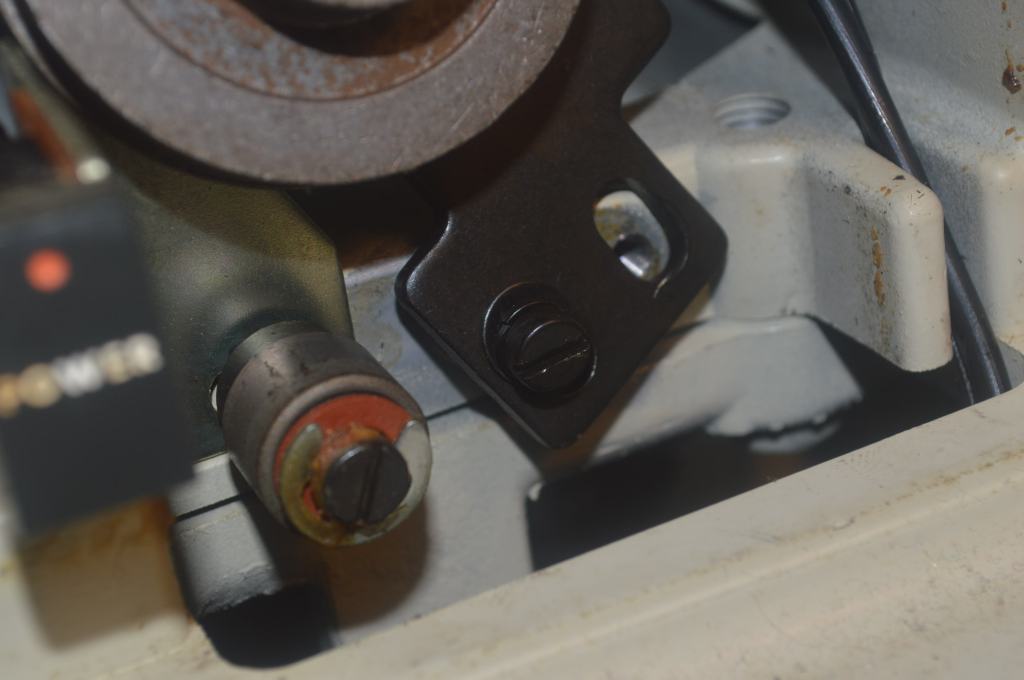

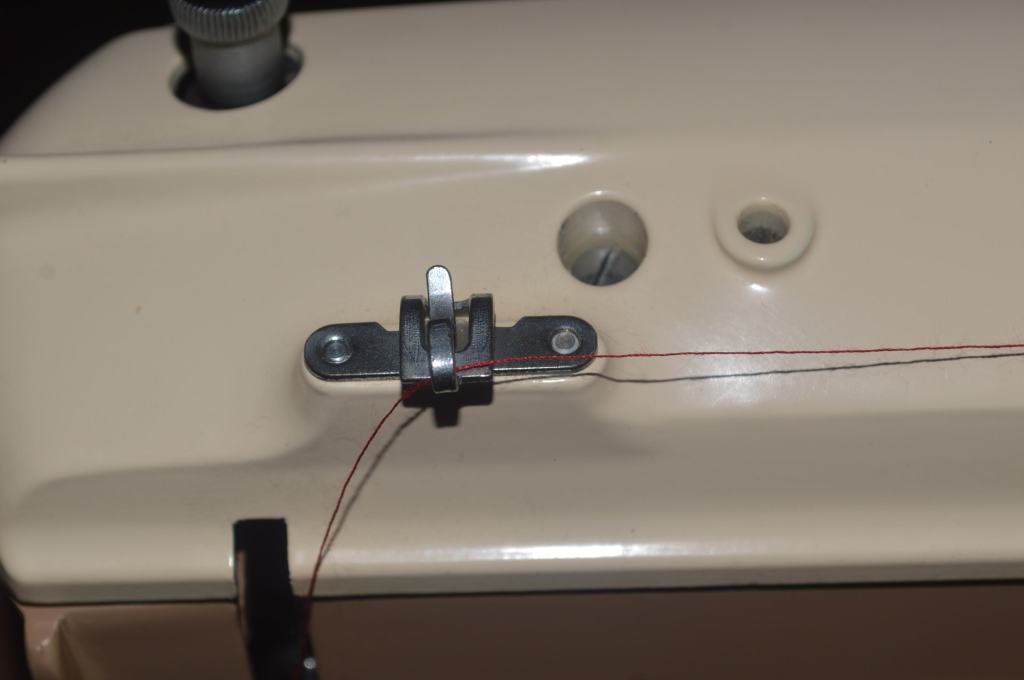

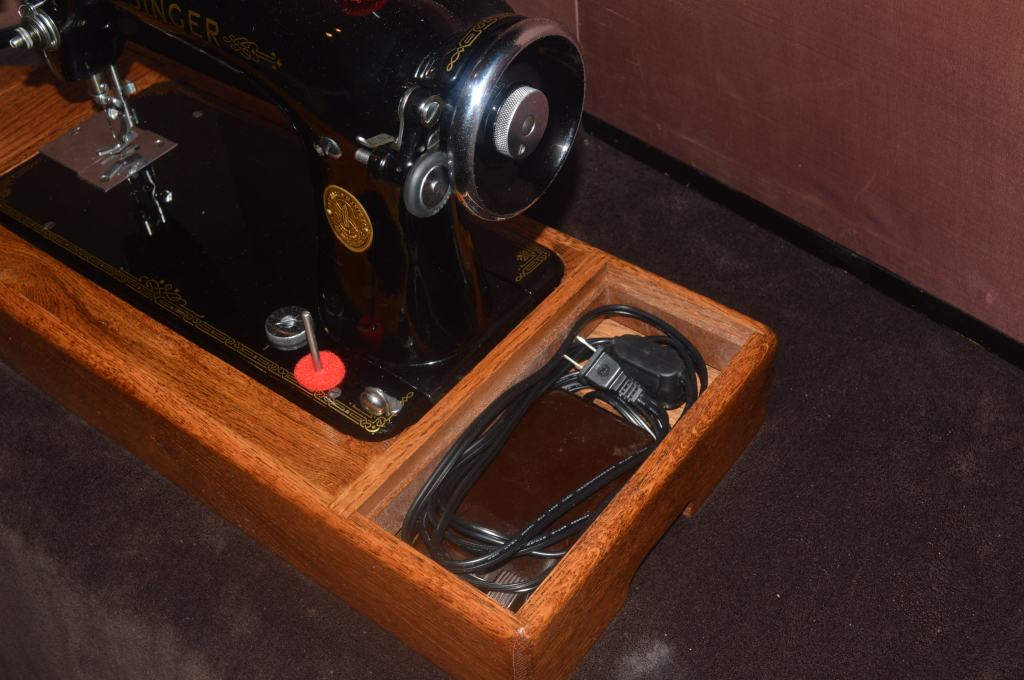

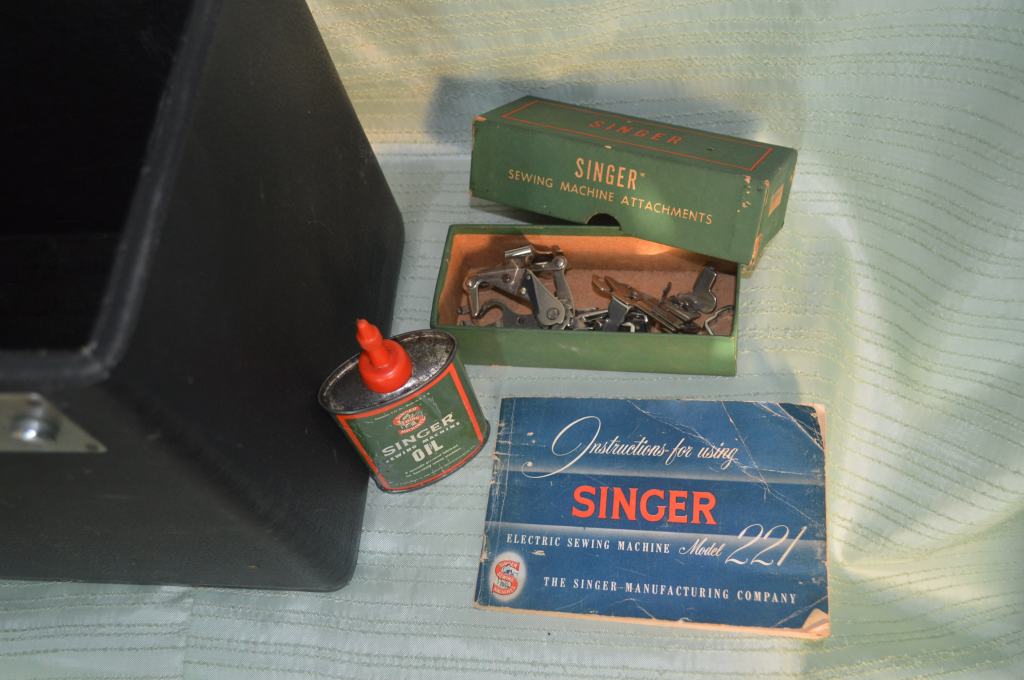

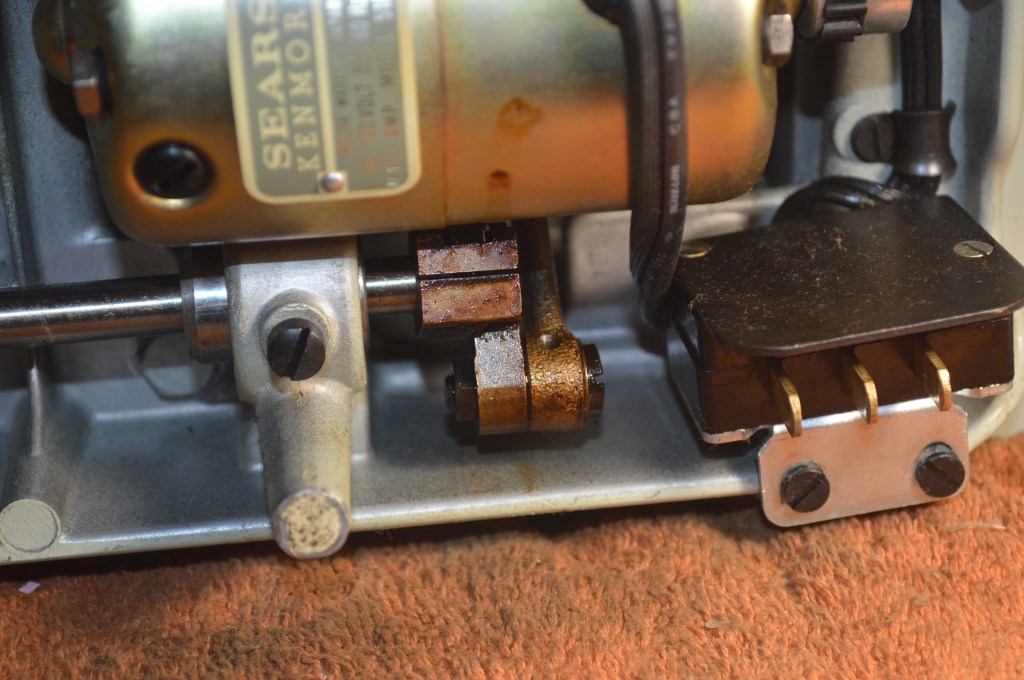

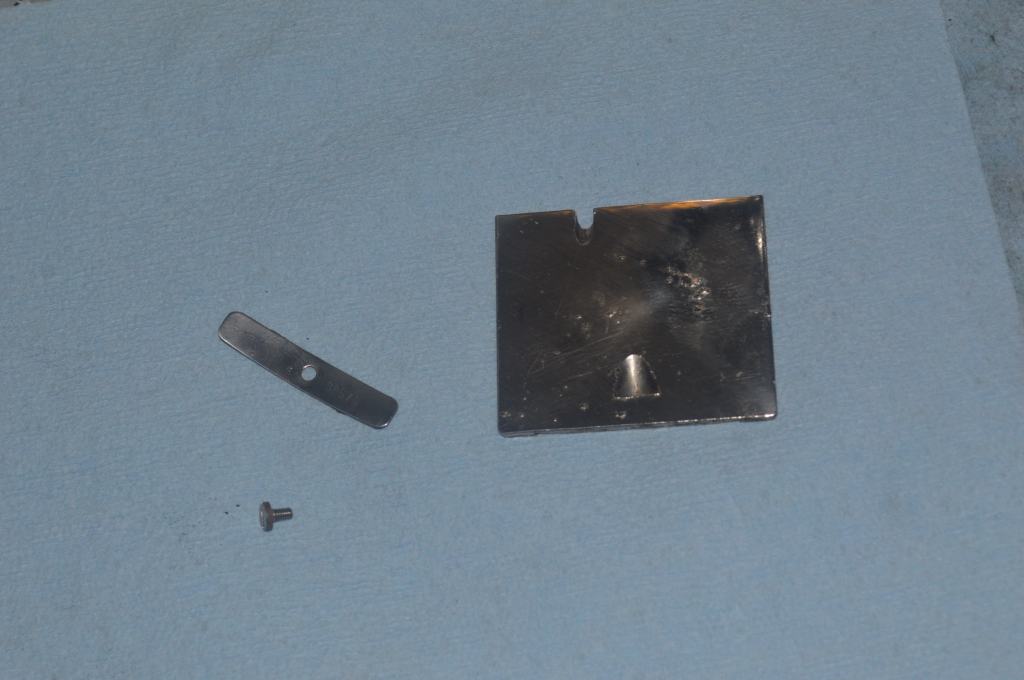

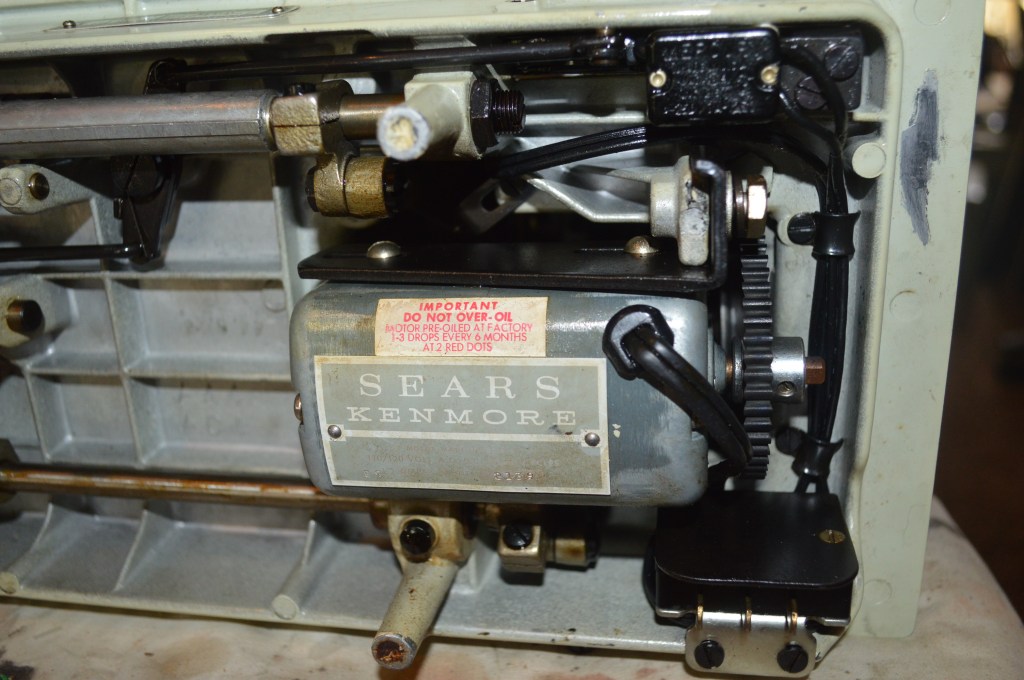

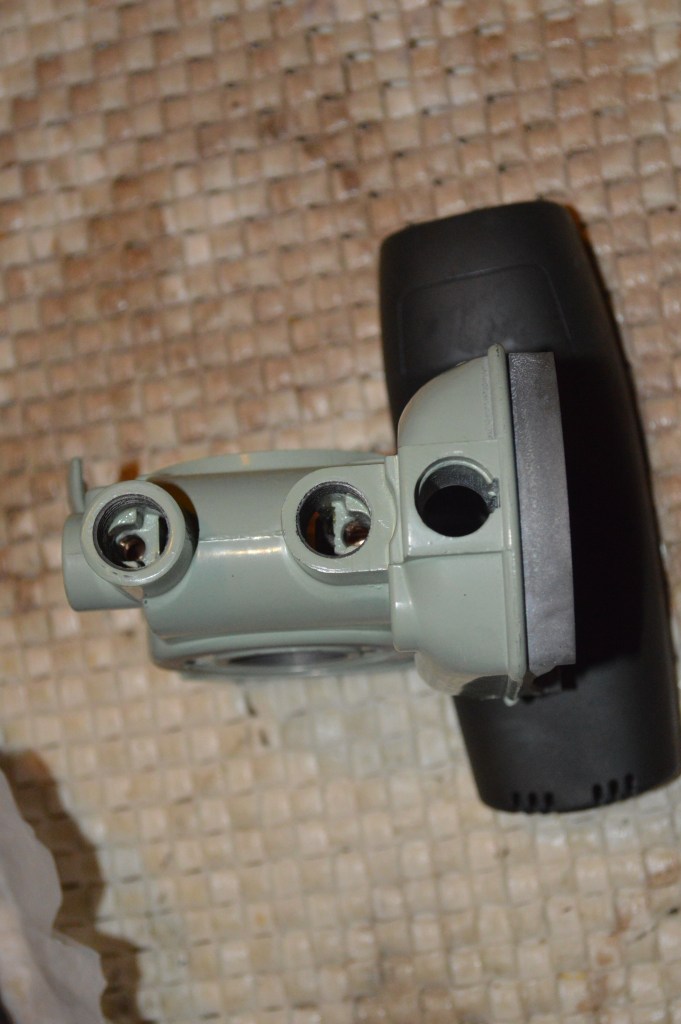

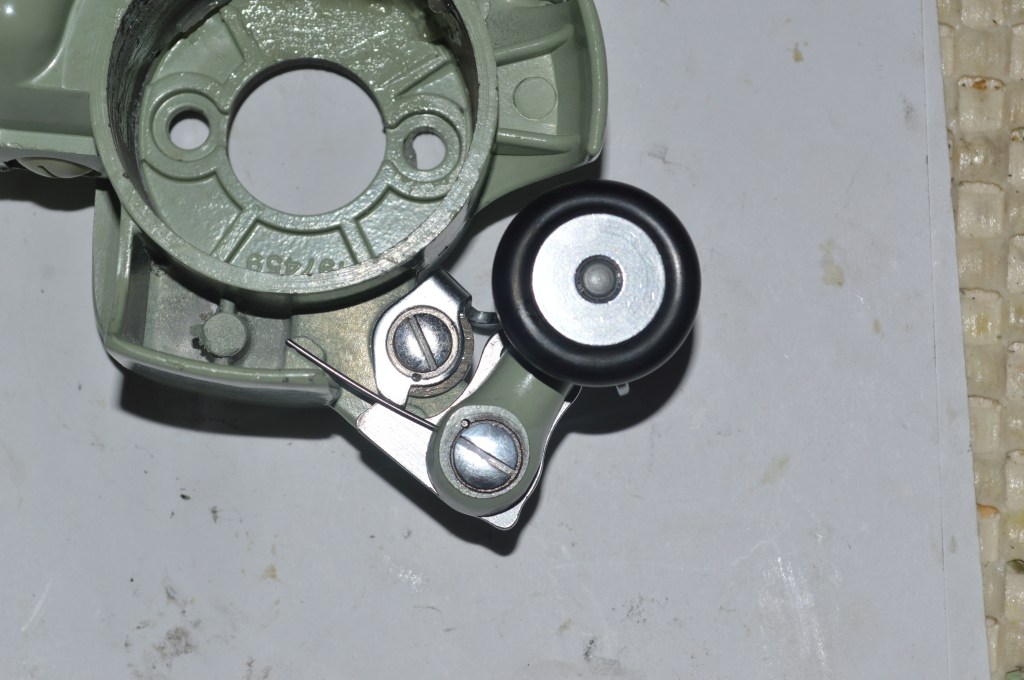

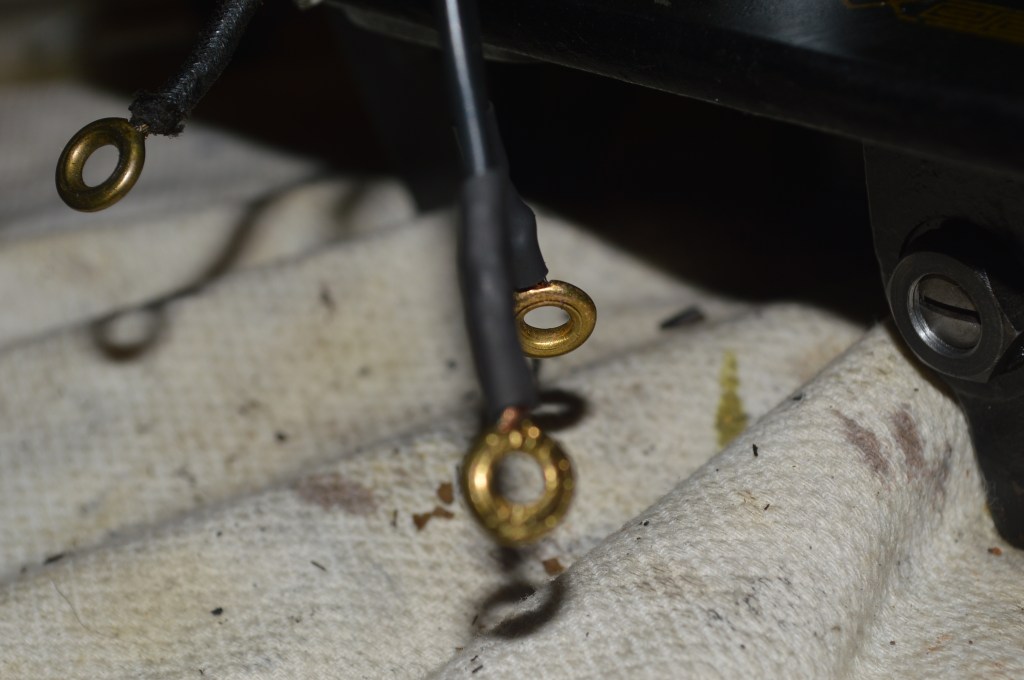

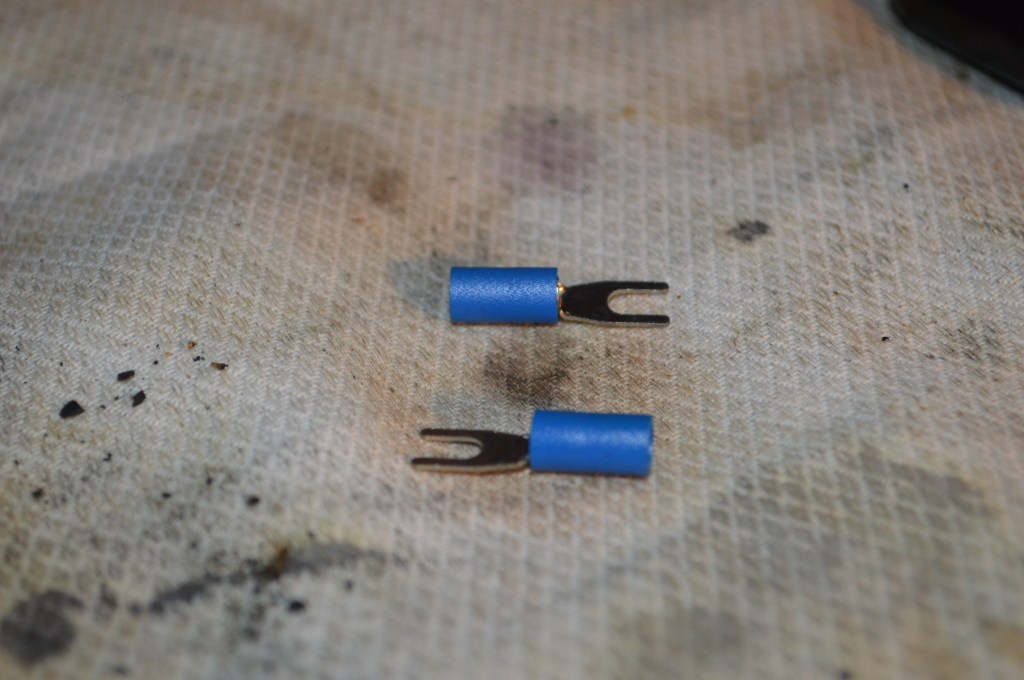

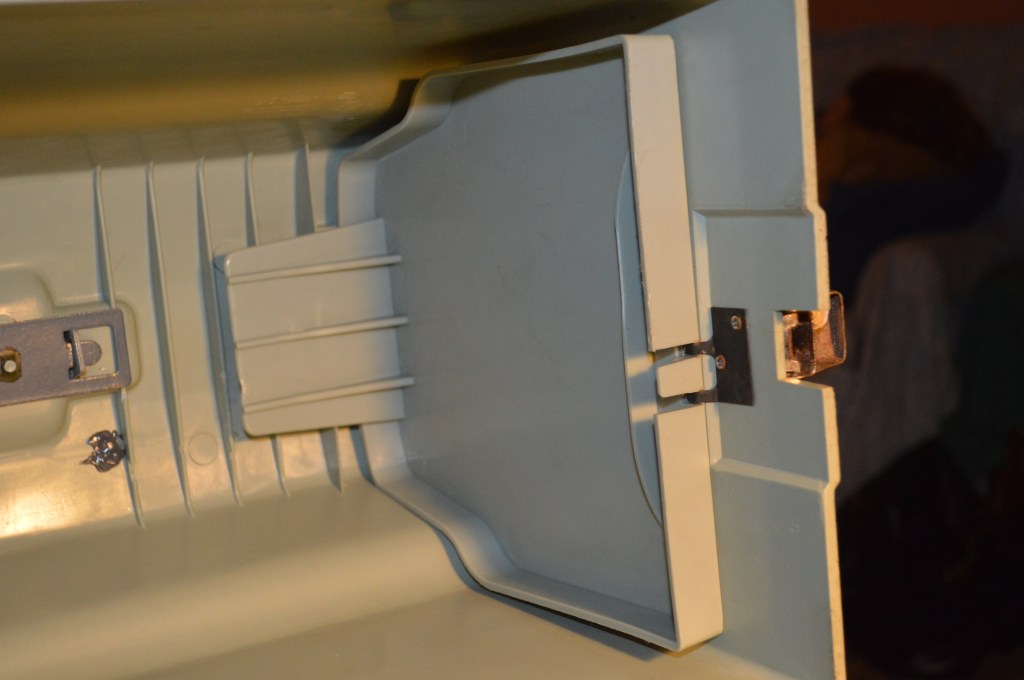

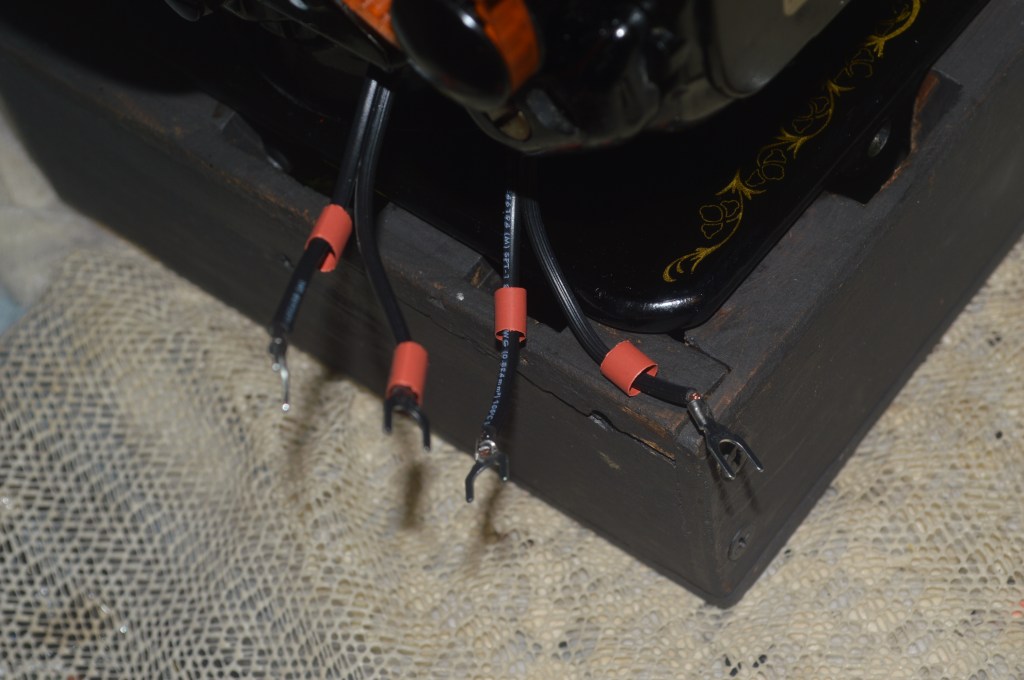

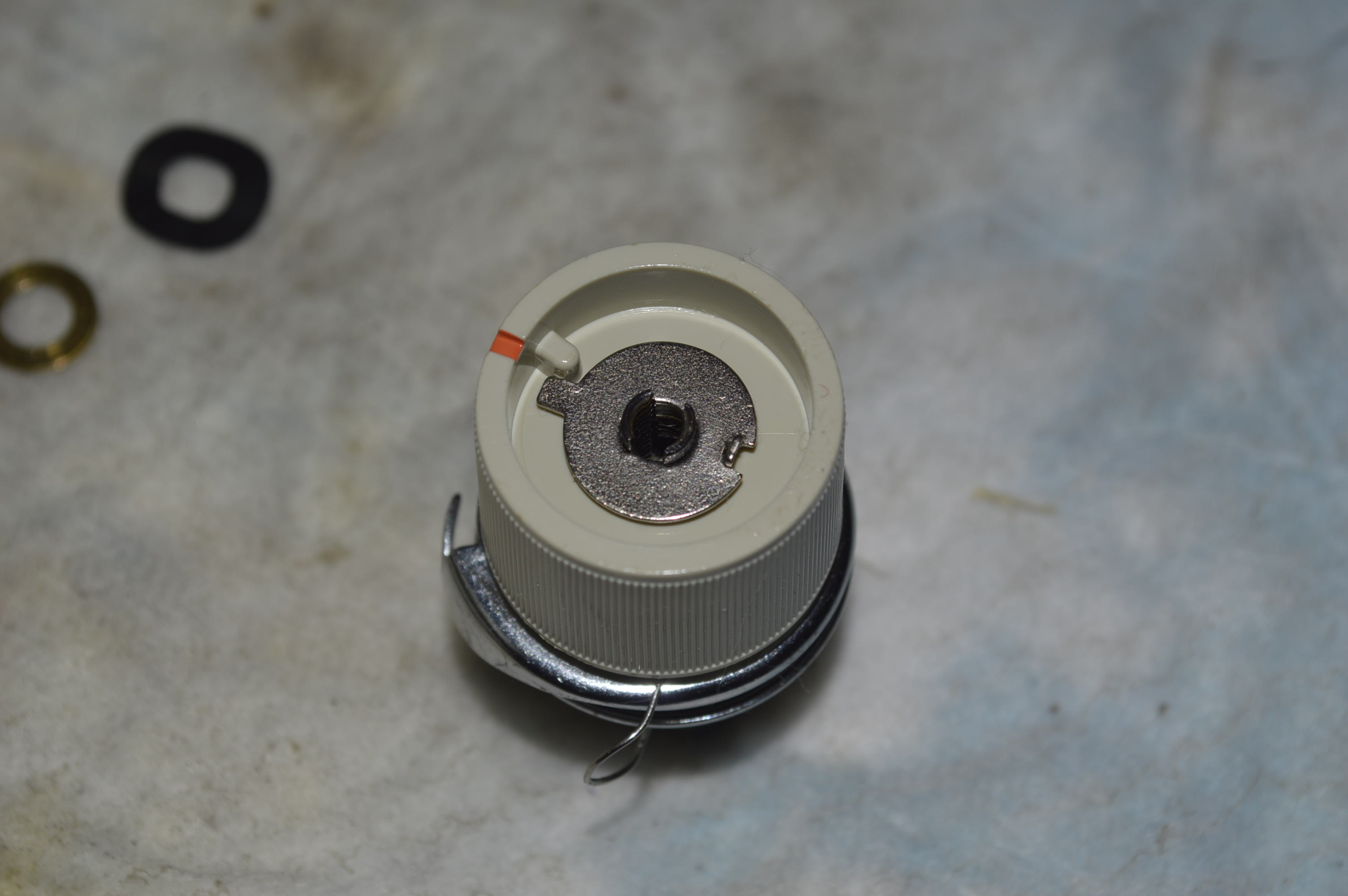

My customer has opted to replace the foot controller. In addition, a new motor/light terminal block is provided.

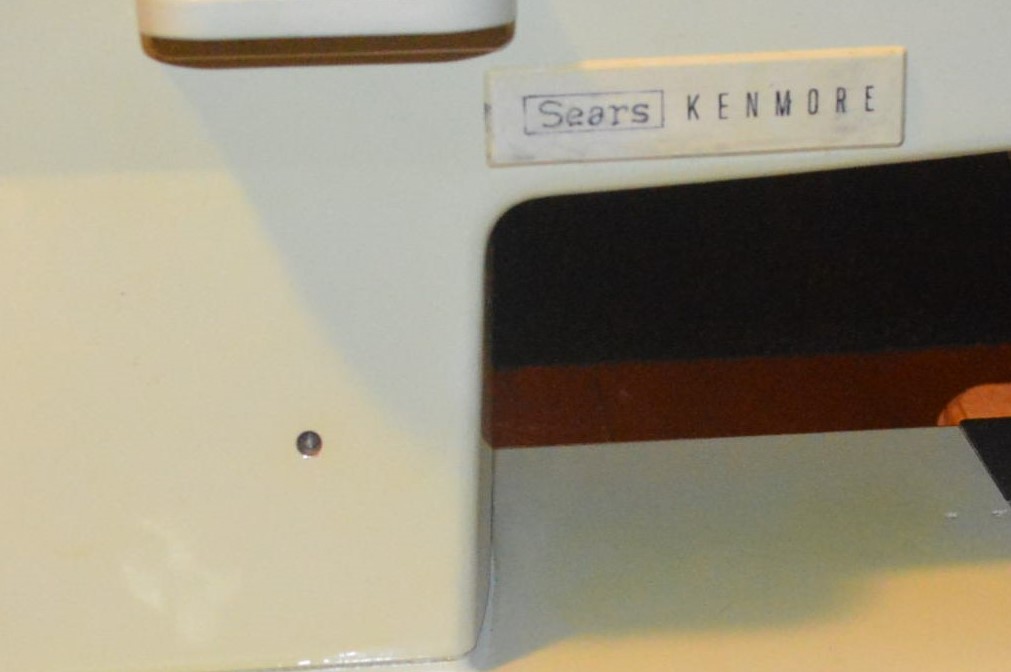

Notice the name on the controller? Its a vintage Kenmore foot controller. The more I use these, the better I like them. Thet are just the right size, have a great heft and feel, operate smoothly, and have very good motor speed control. They are a carbon pile controller and they run much cooler than resistance style foot controllers (the type of controller the machine came with).

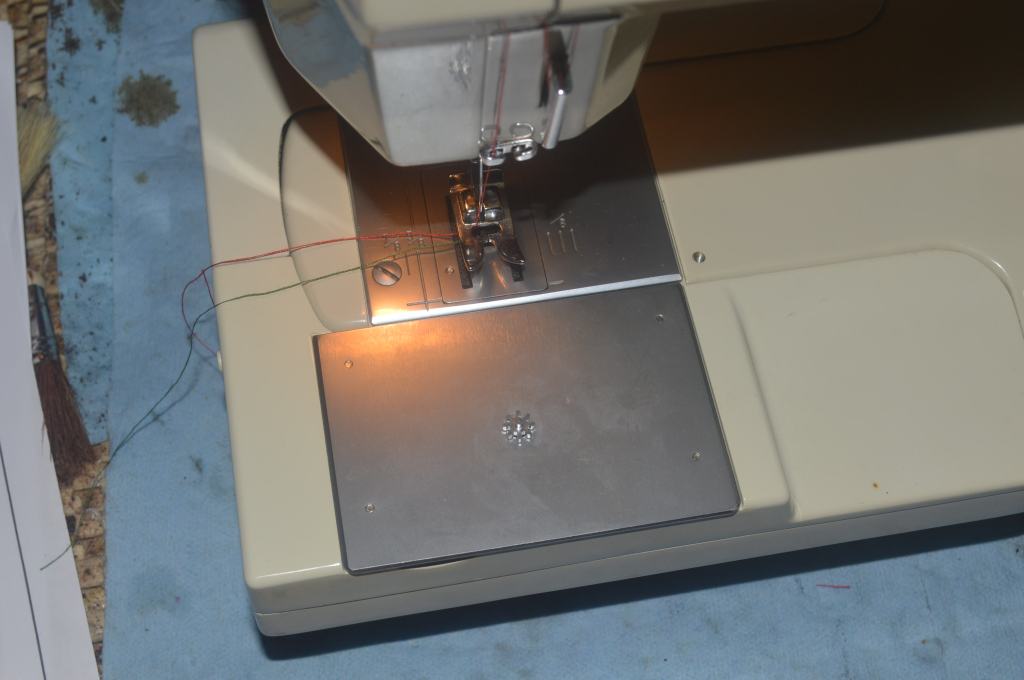

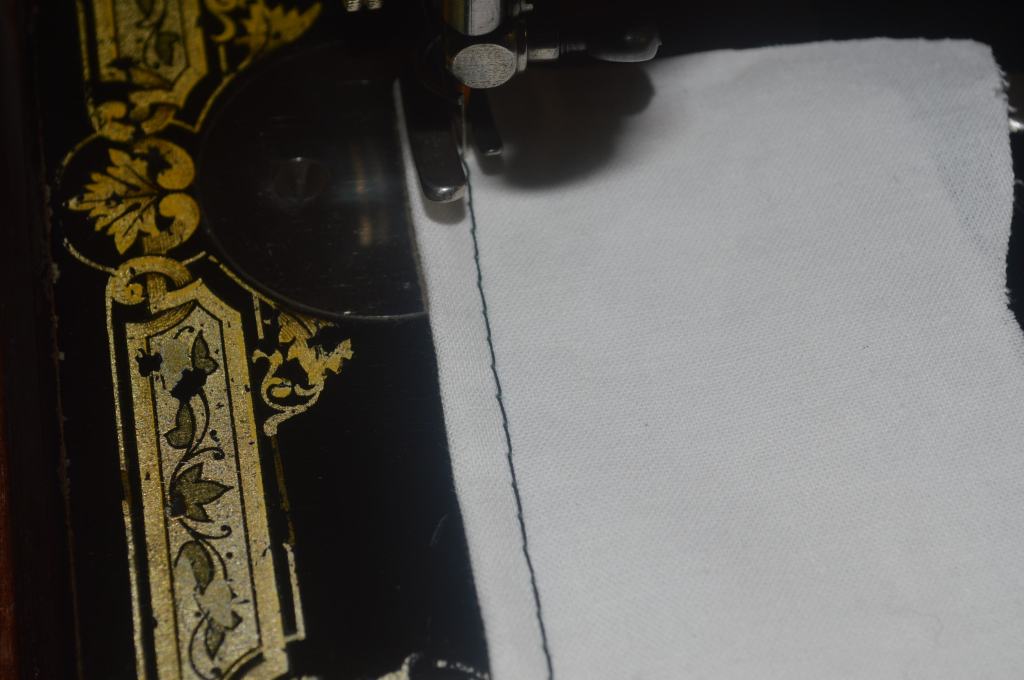

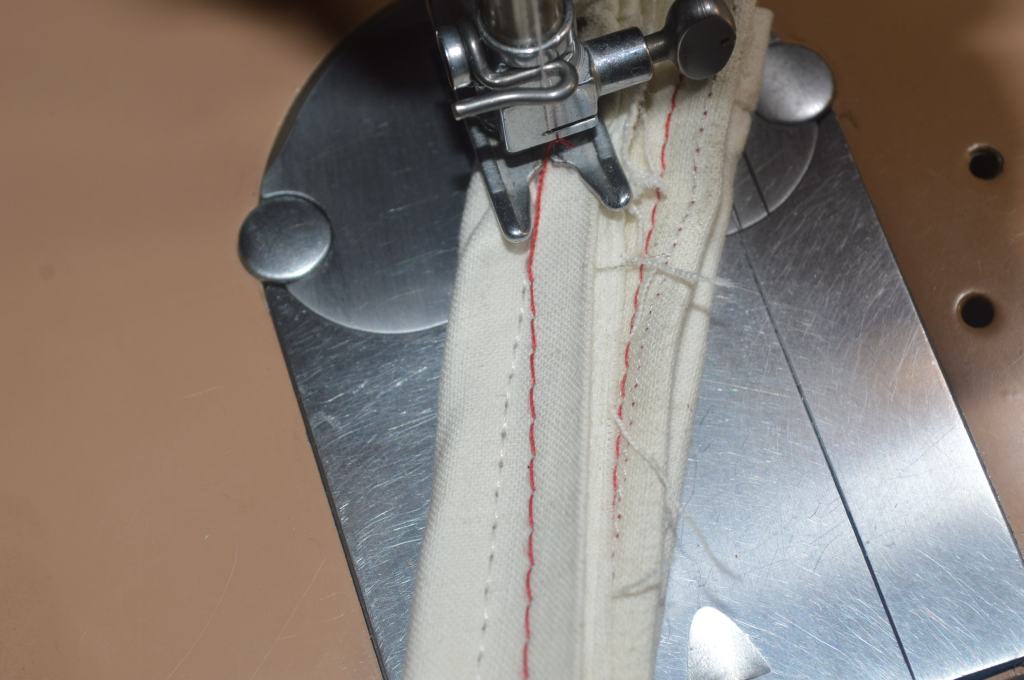

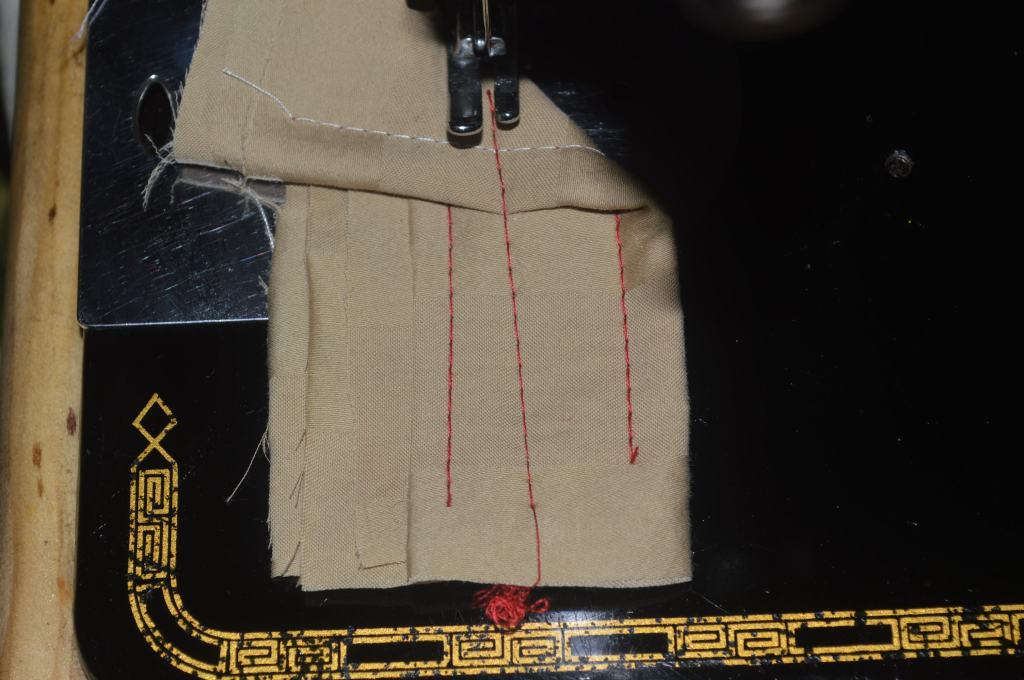

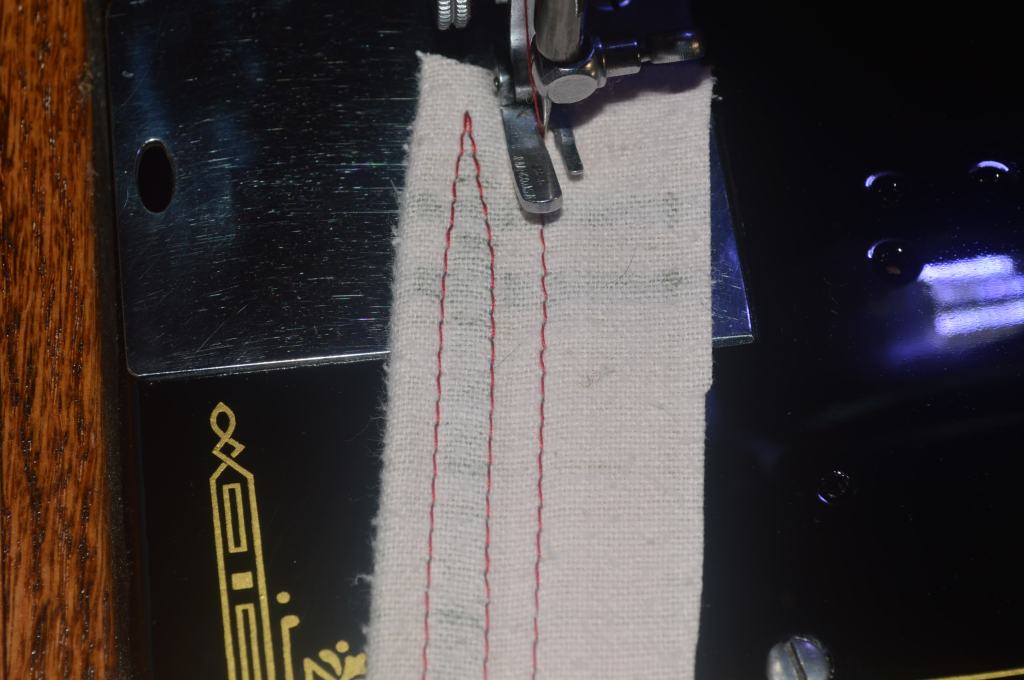

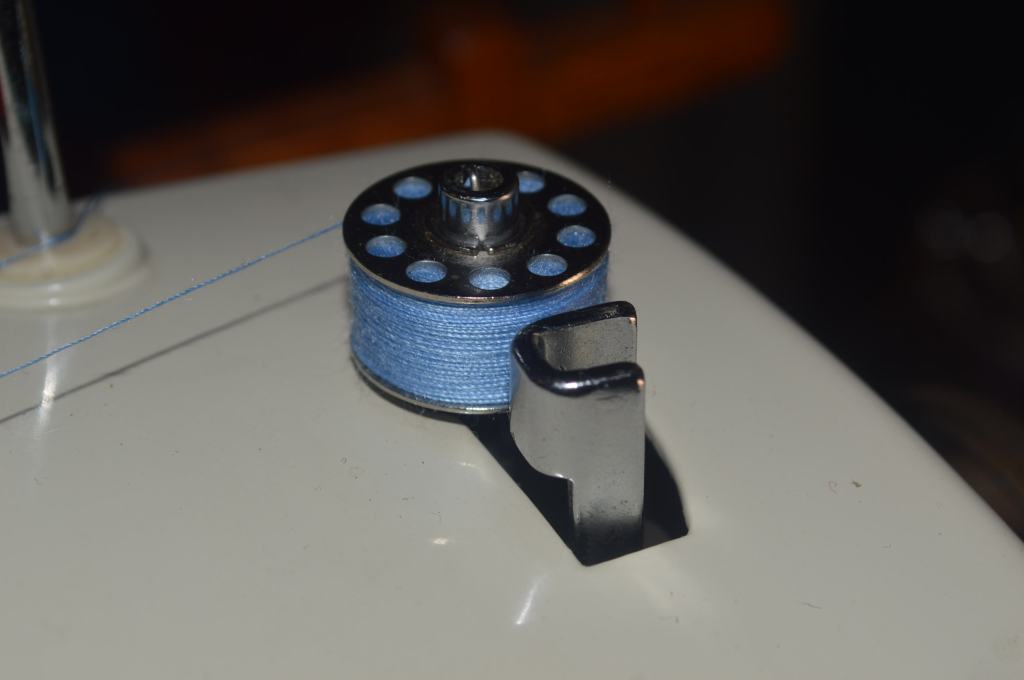

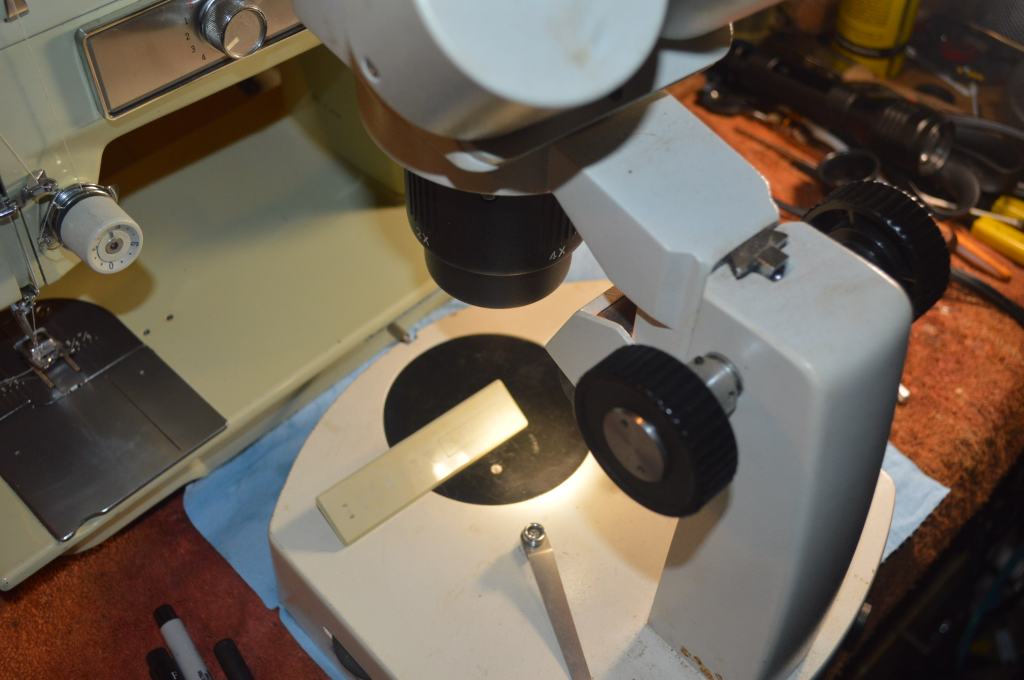

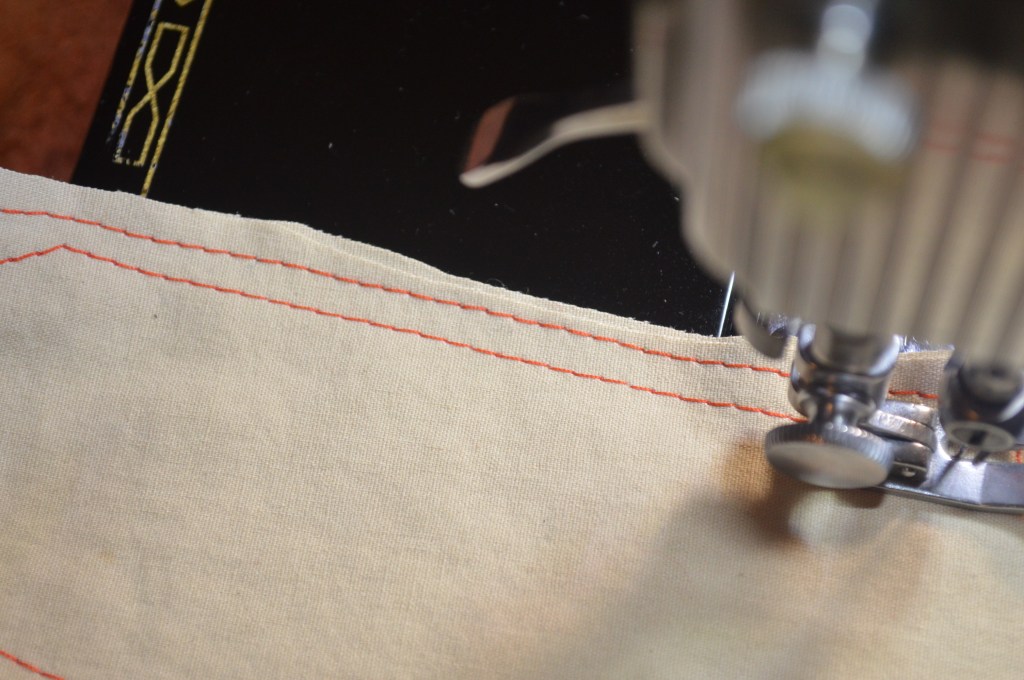

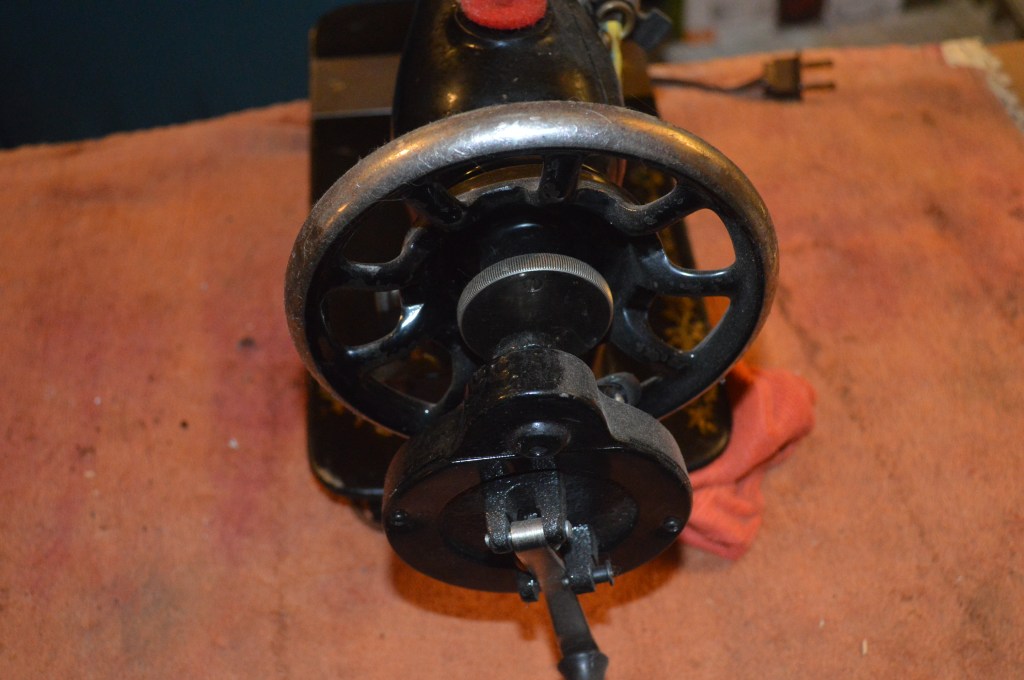

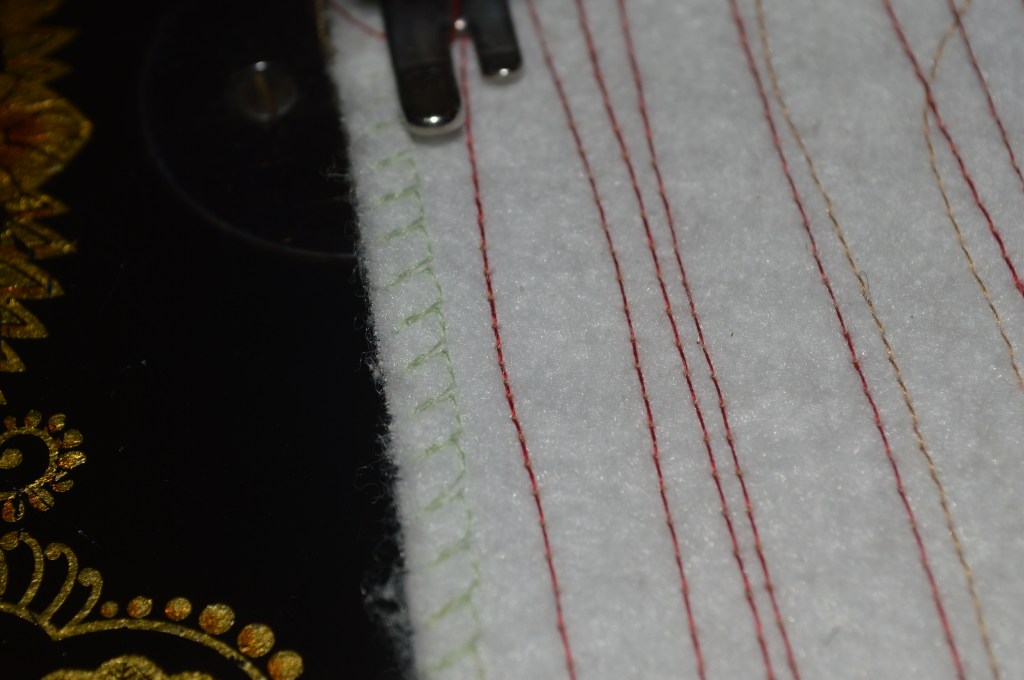

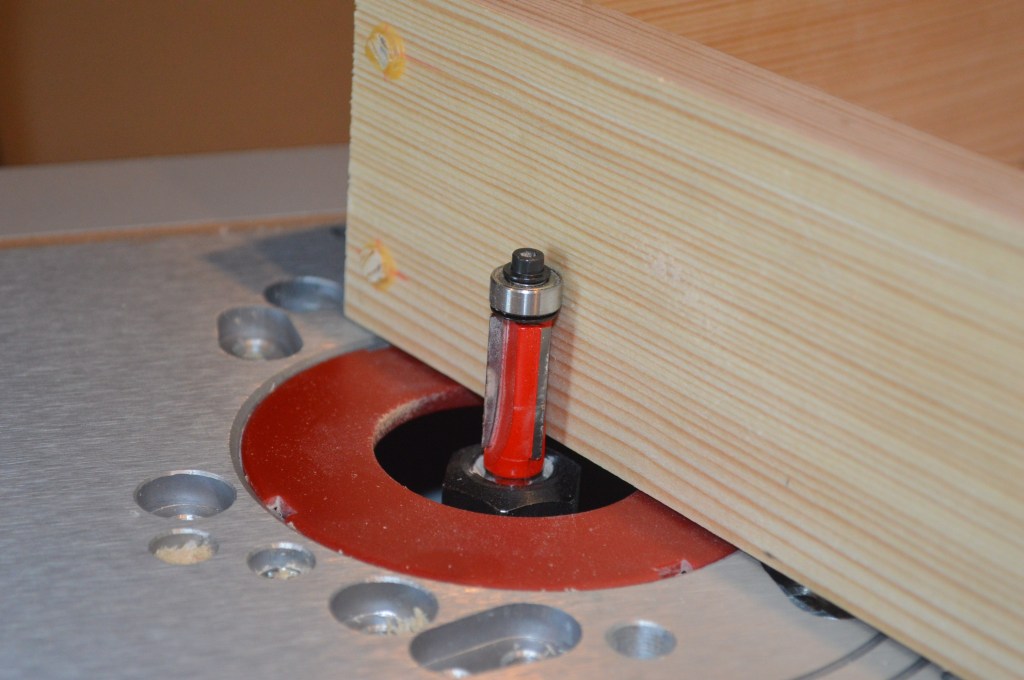

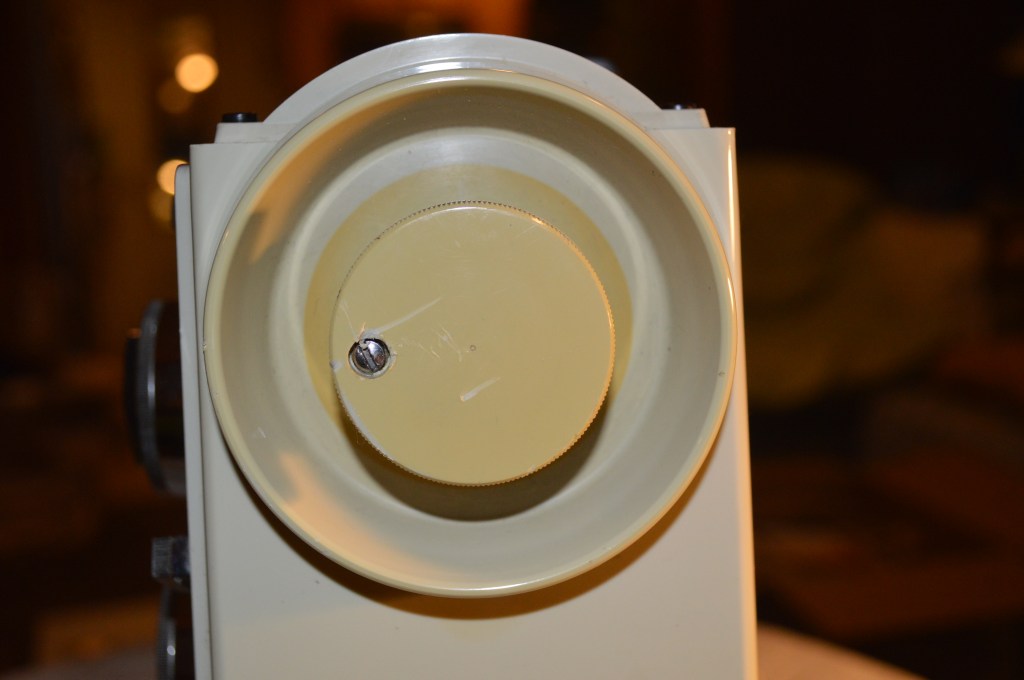

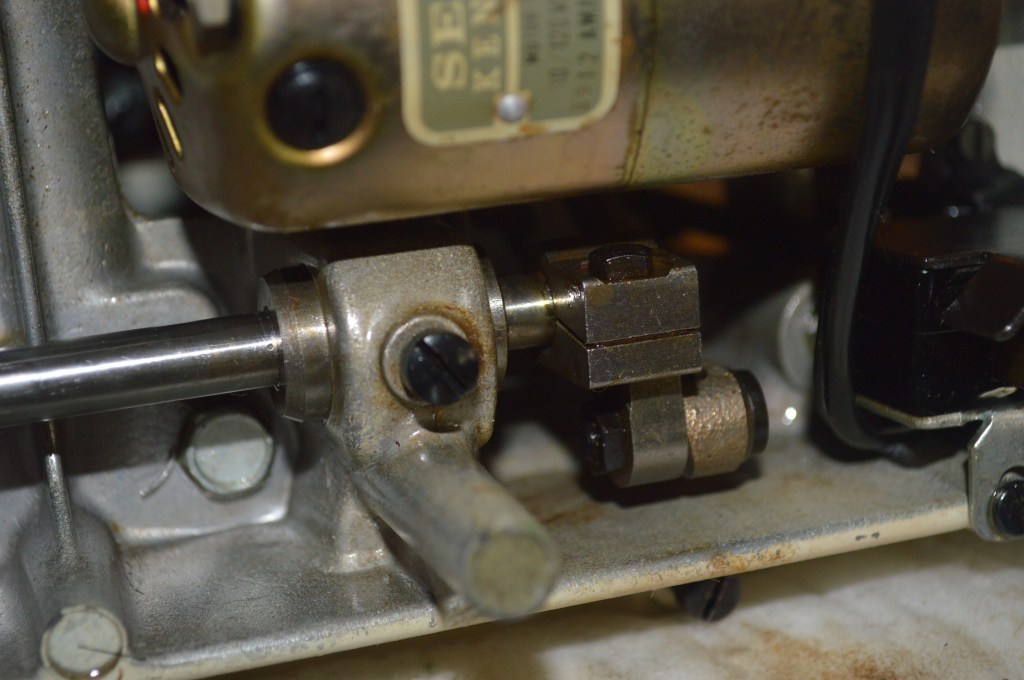

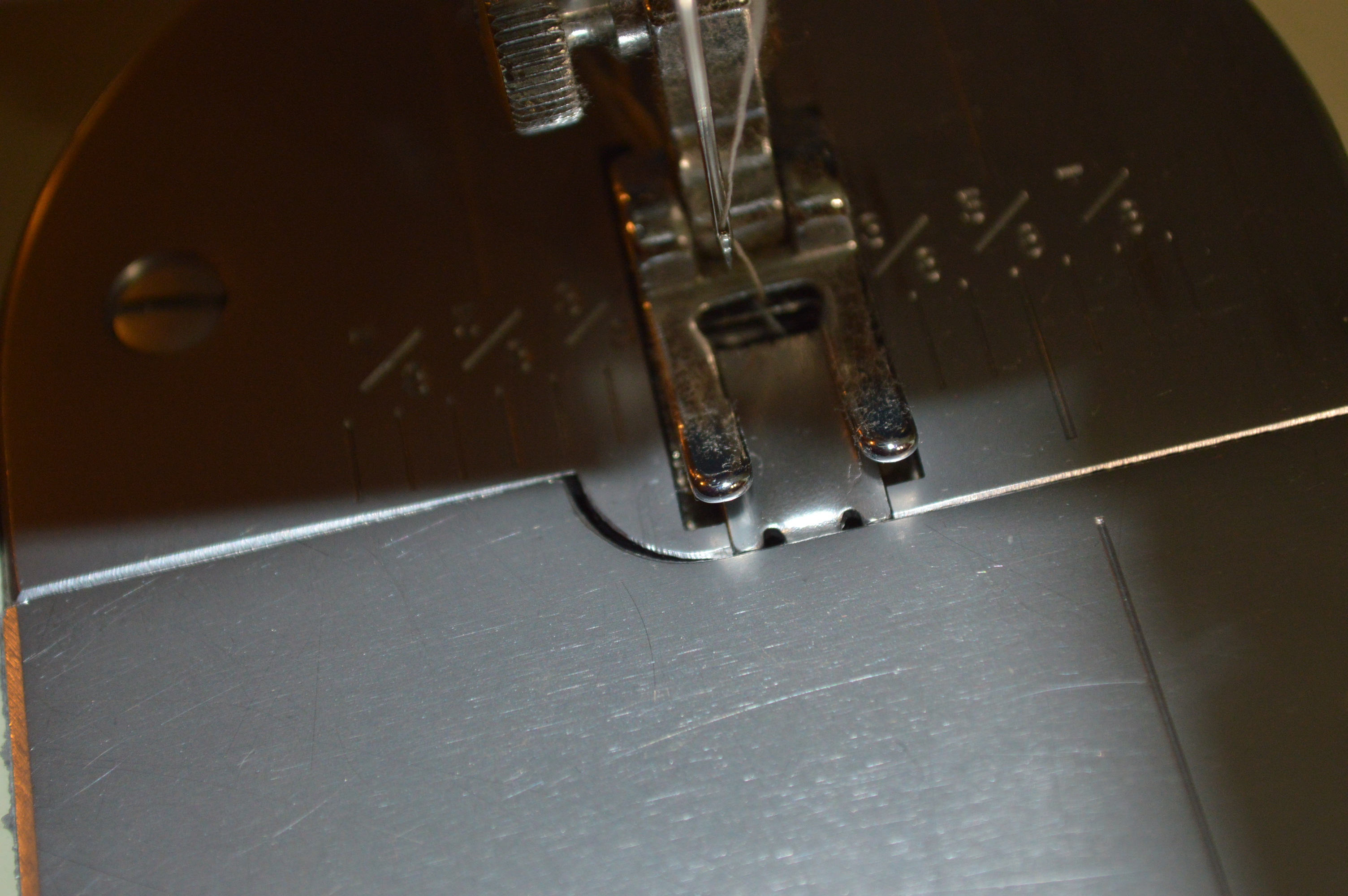

The machine’s sewing mechanisms are reassembled and rough adjustments are made. It is then hooked up to an external electric motor and run for 5 minutes at 1400 rpm. This mates all of the moving parts together and makes the machine incredibly smooth. After this exercise, fine adjustments are made and the motor, light, and all of the bits and pieces are reassembled to the machine.

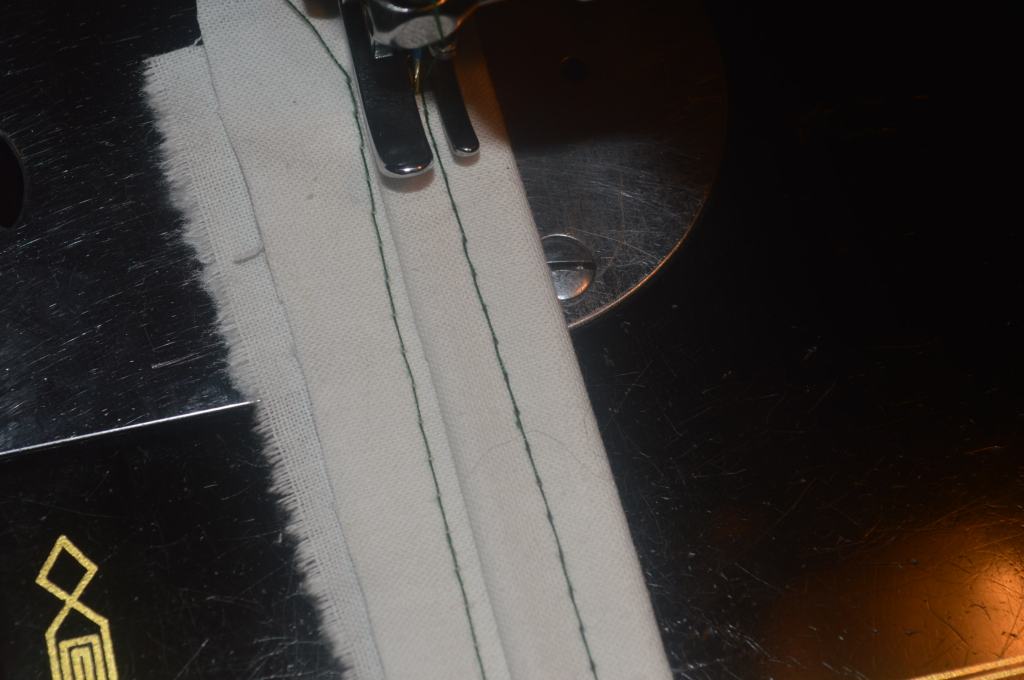

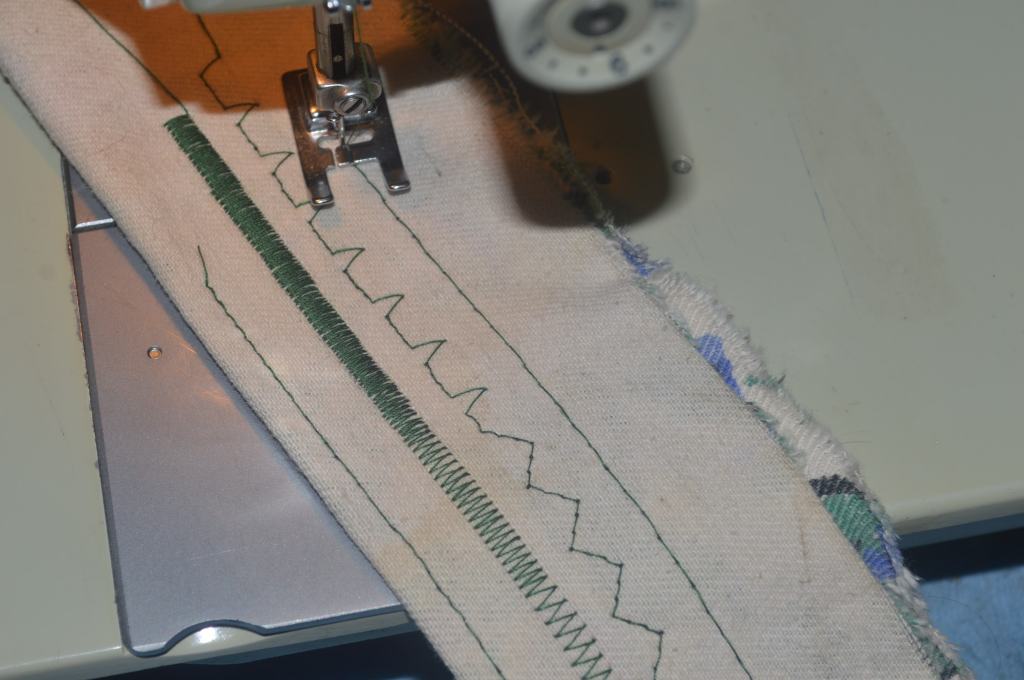

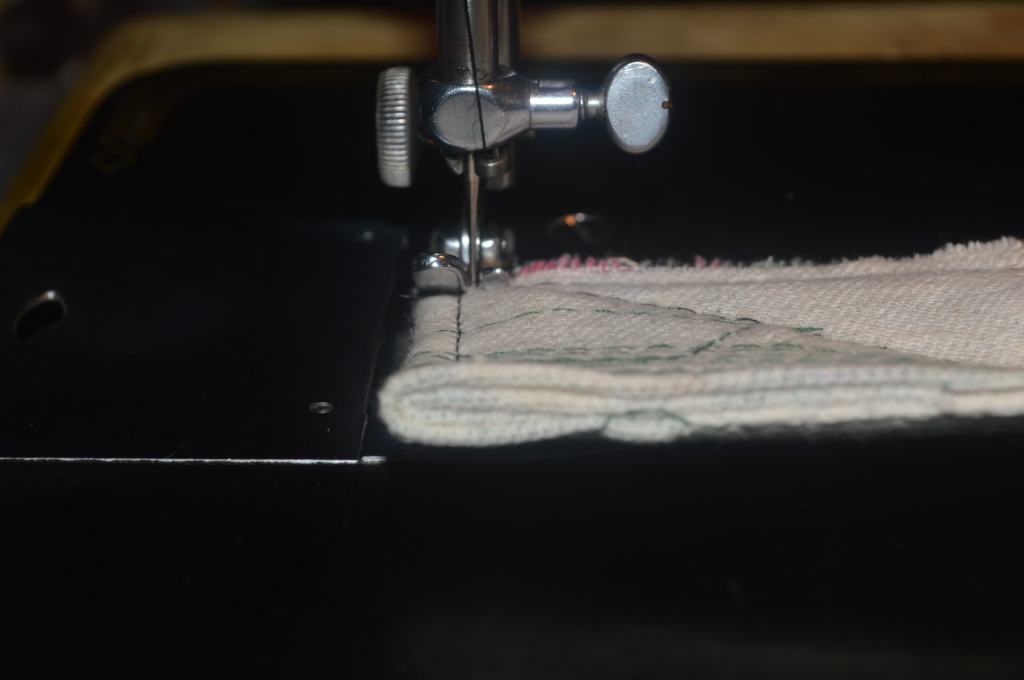

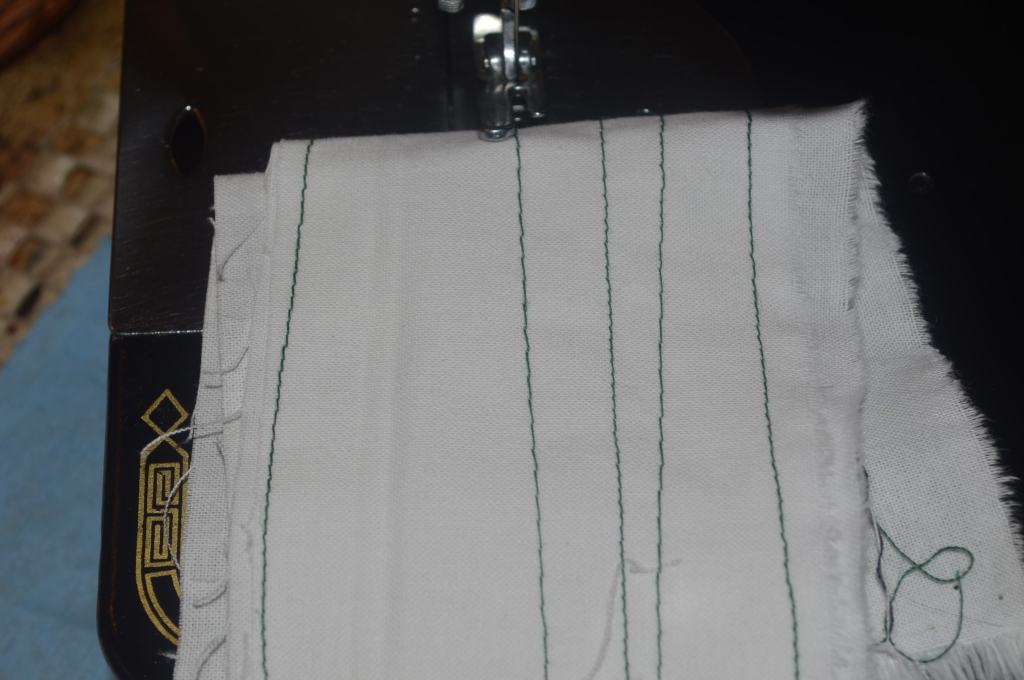

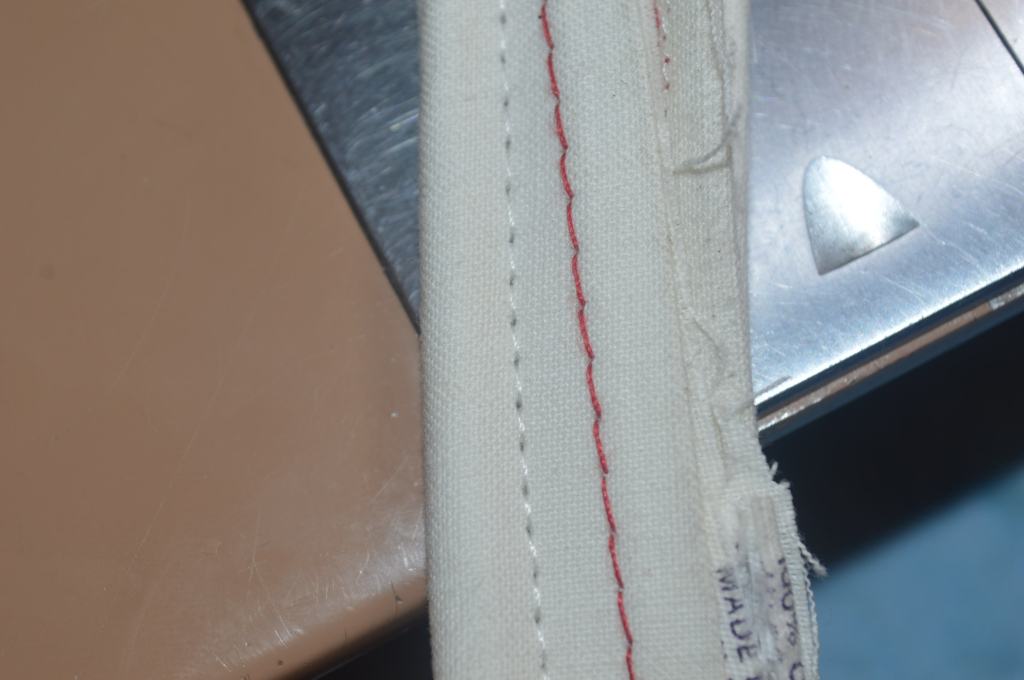

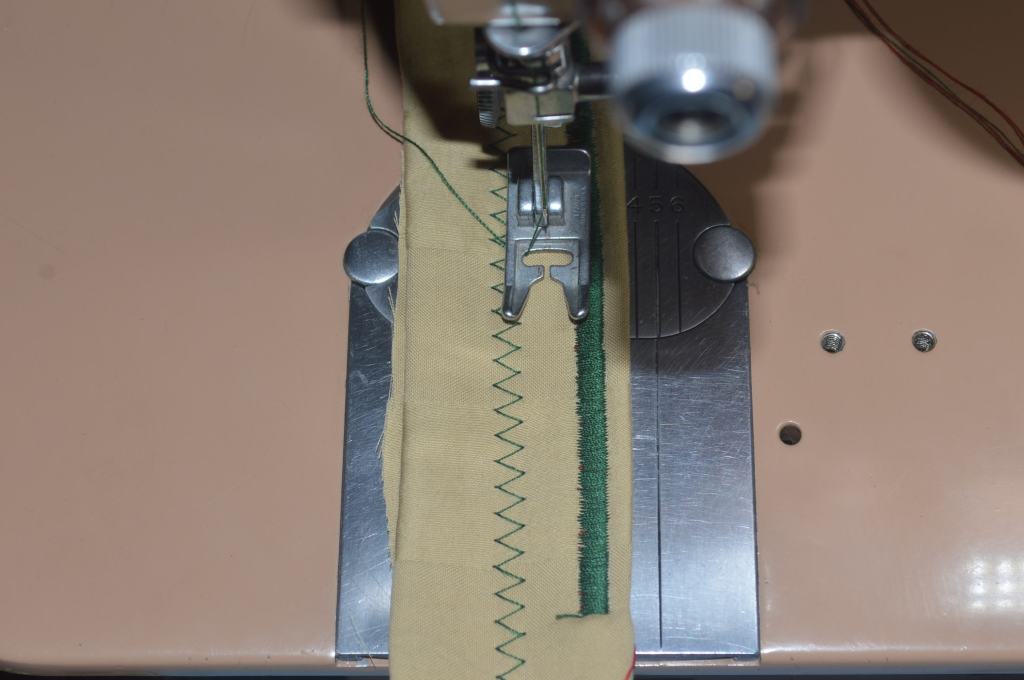

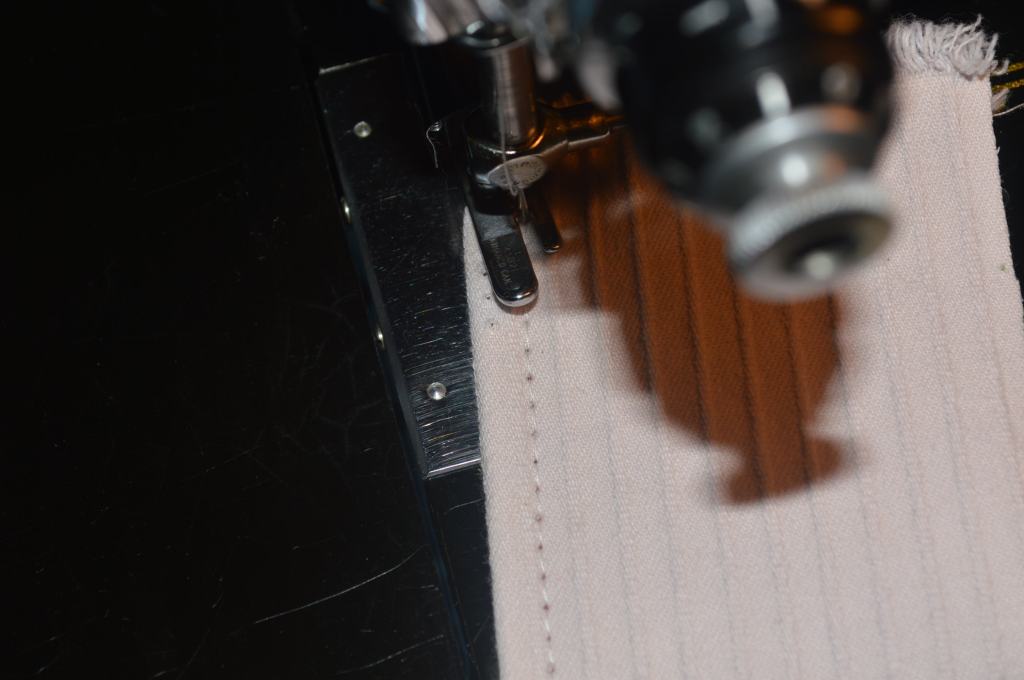

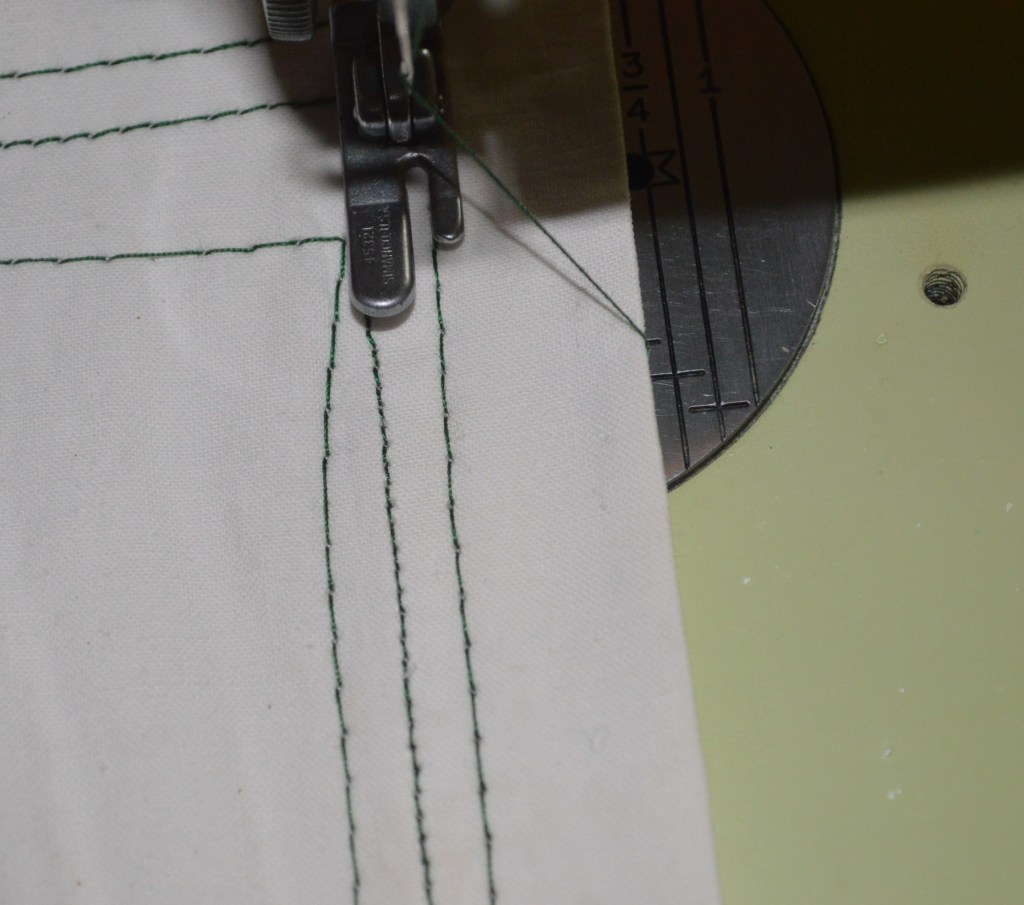

At this point, the machine is threaded, tensions are set, and the machine is tested to see how she sews! After noodling with the needle depth, top and bottom tensions, and presser foot pressure, I’d say it lays down a very nice stitch. I didn’t clock the machine speed, but I would guess it is 1000 spm or better. The machine has a very solid sound and the motor is very strong. I’m very happy with the outcome!

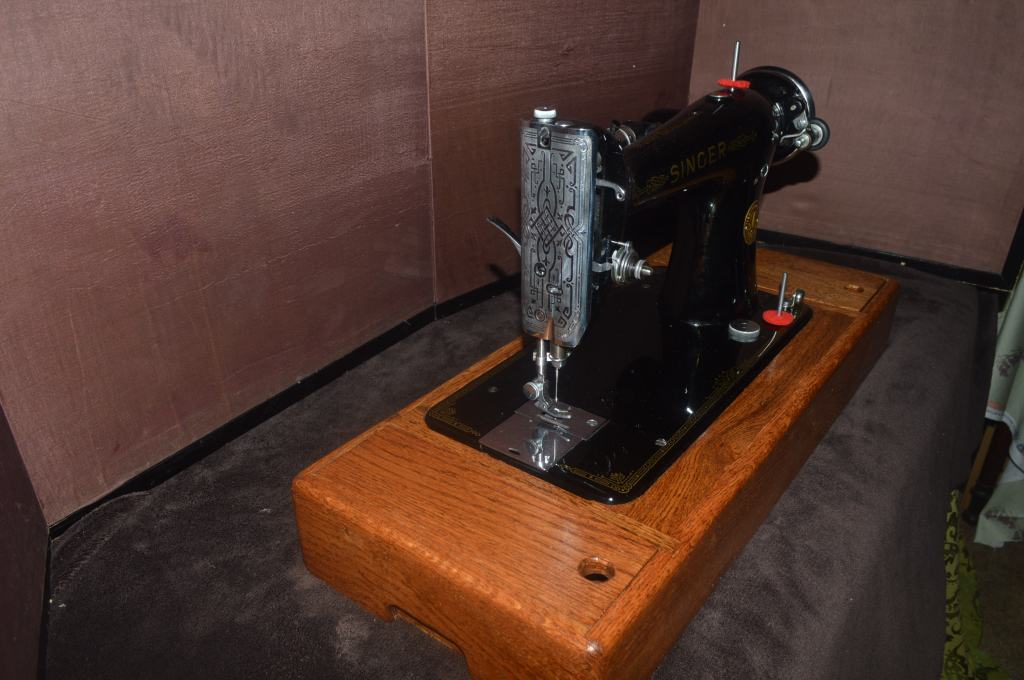

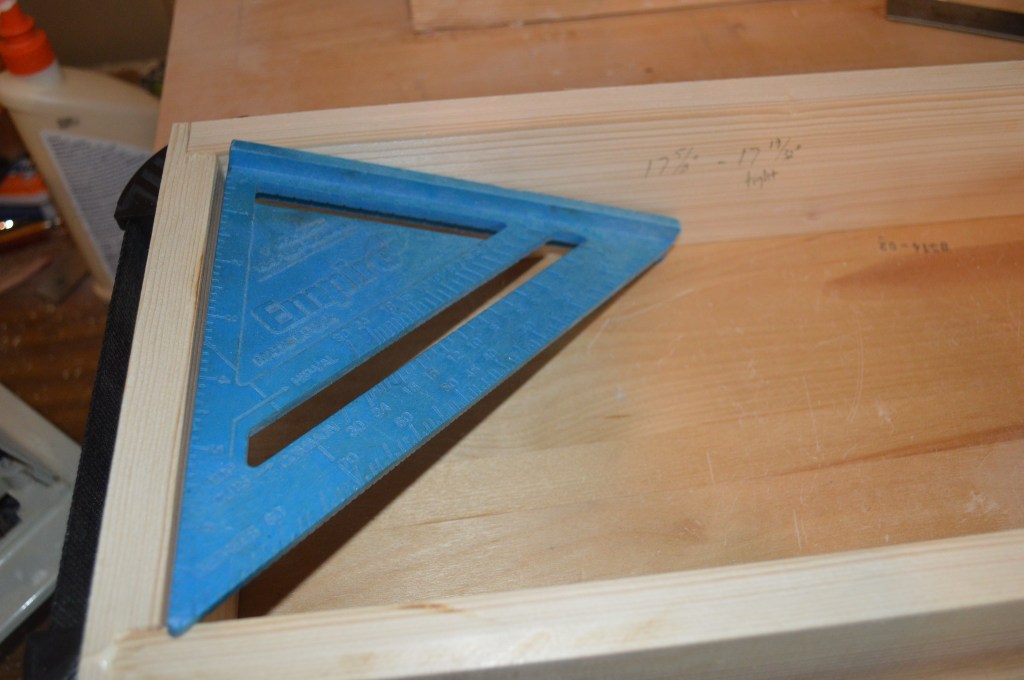

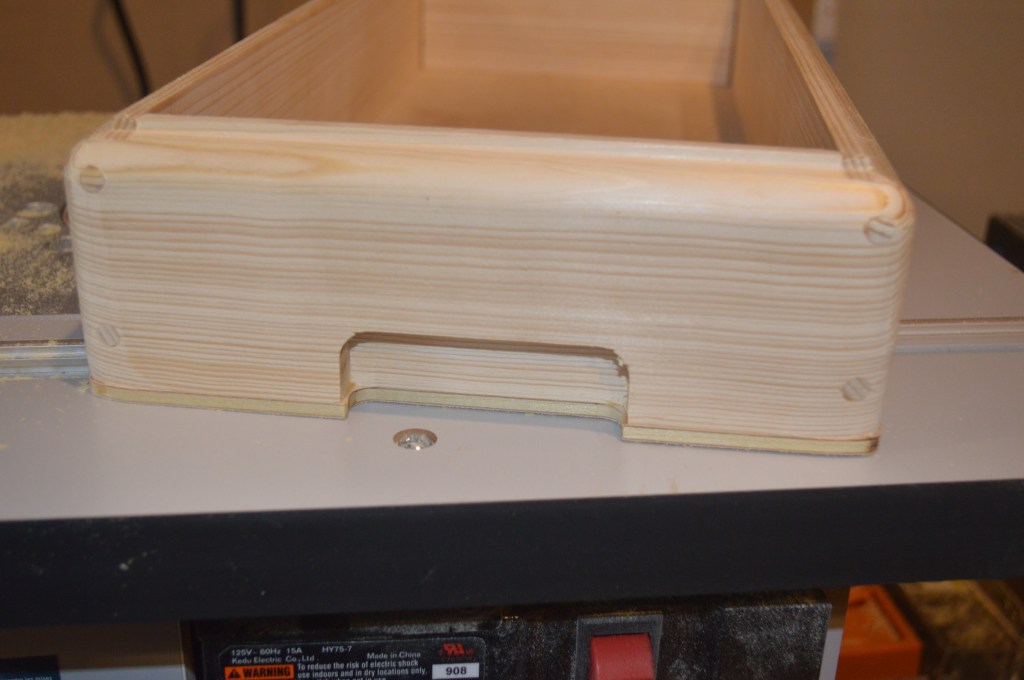

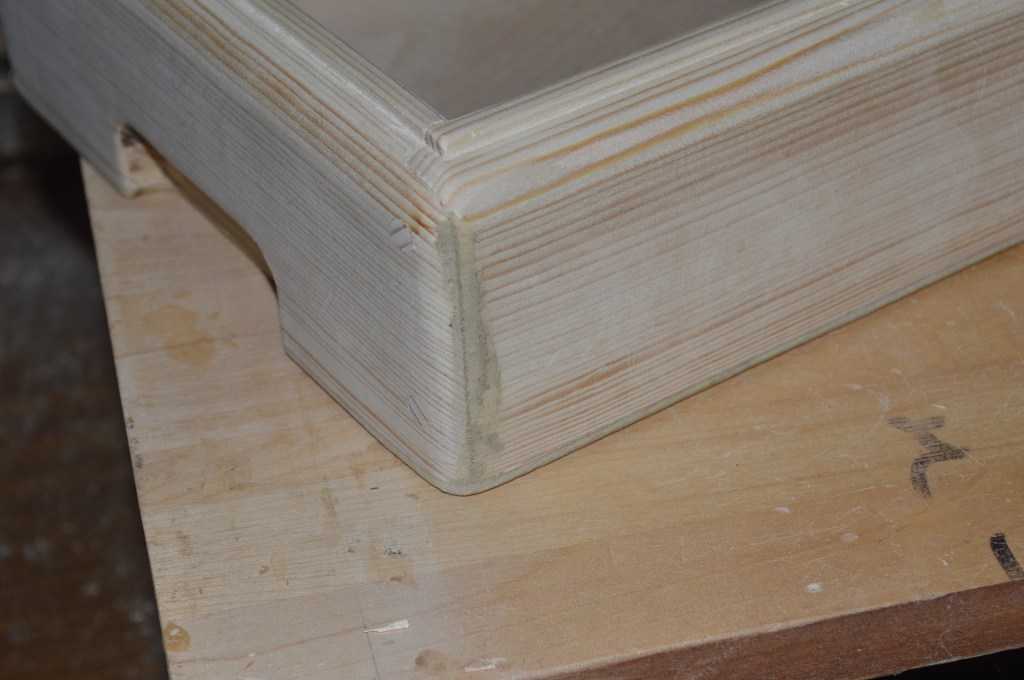

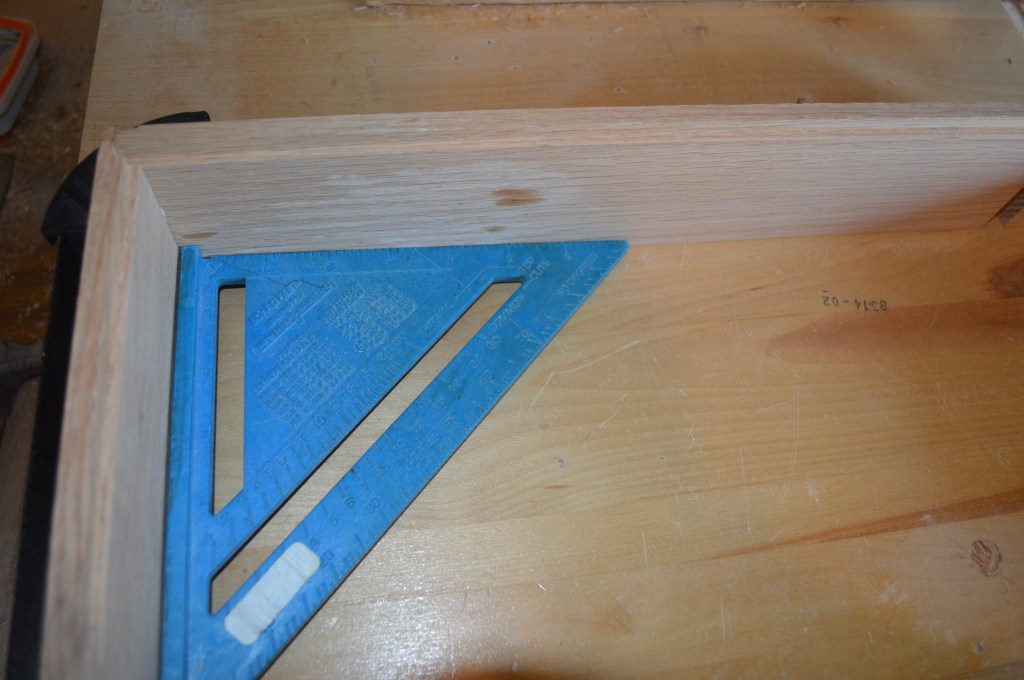

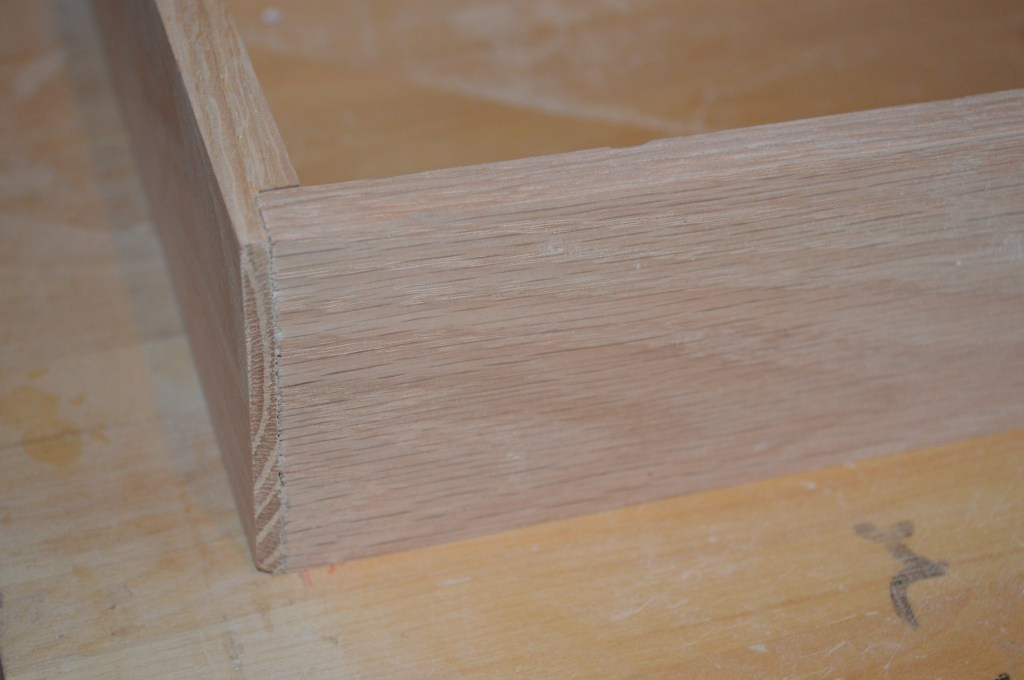

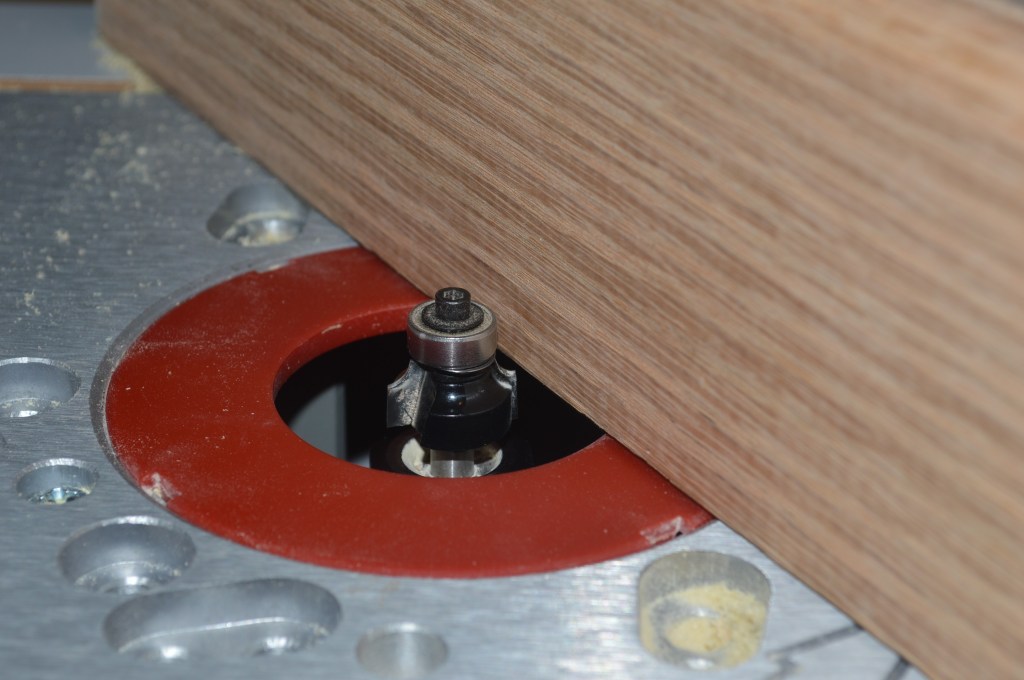

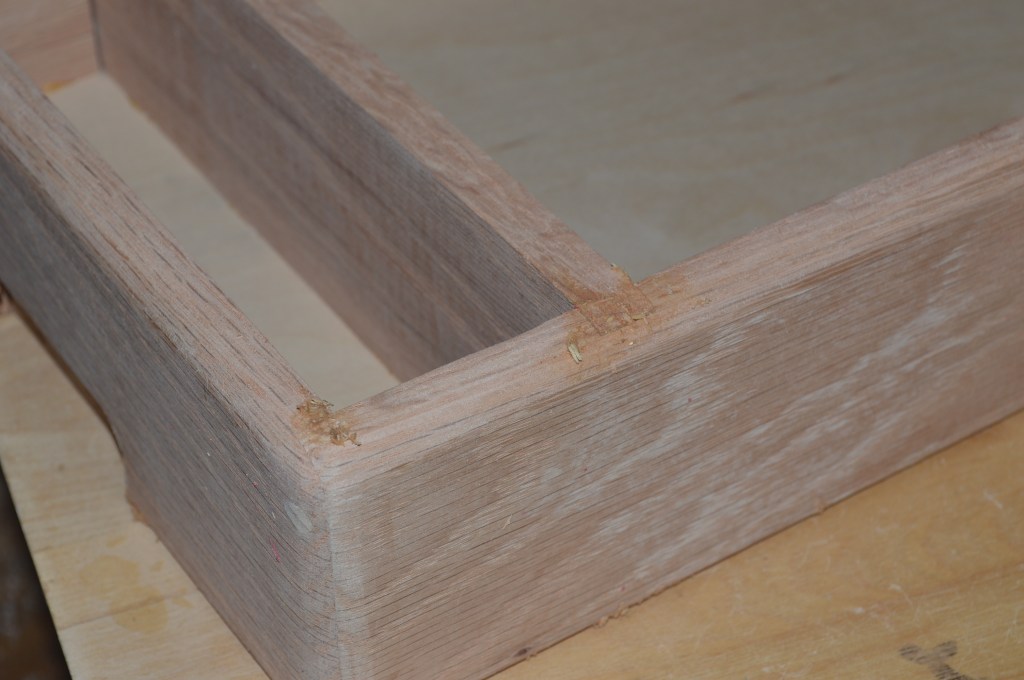

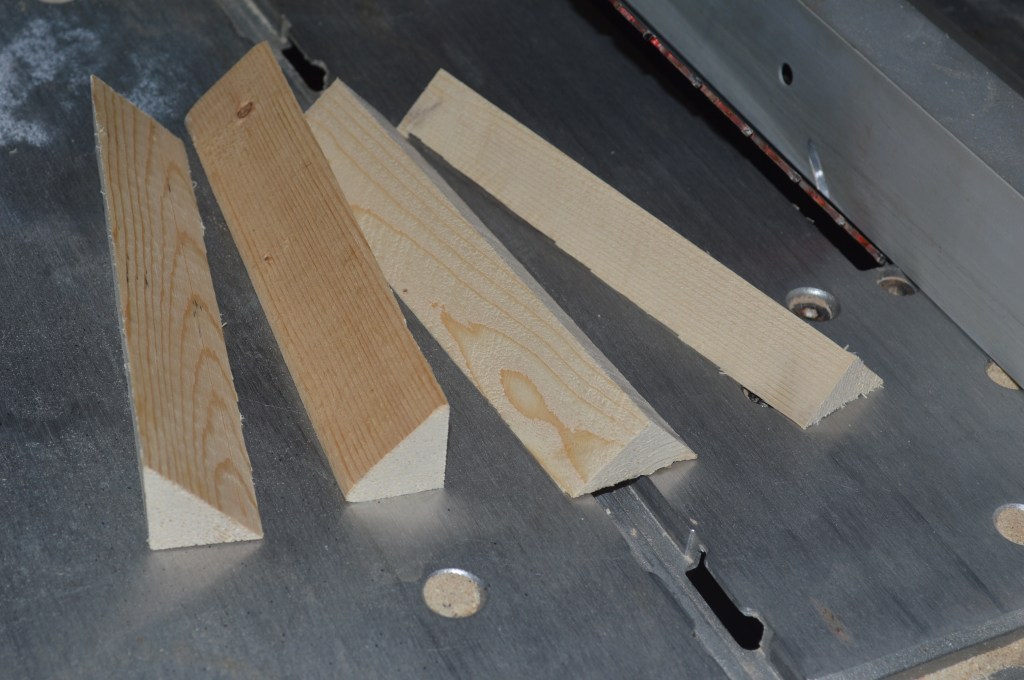

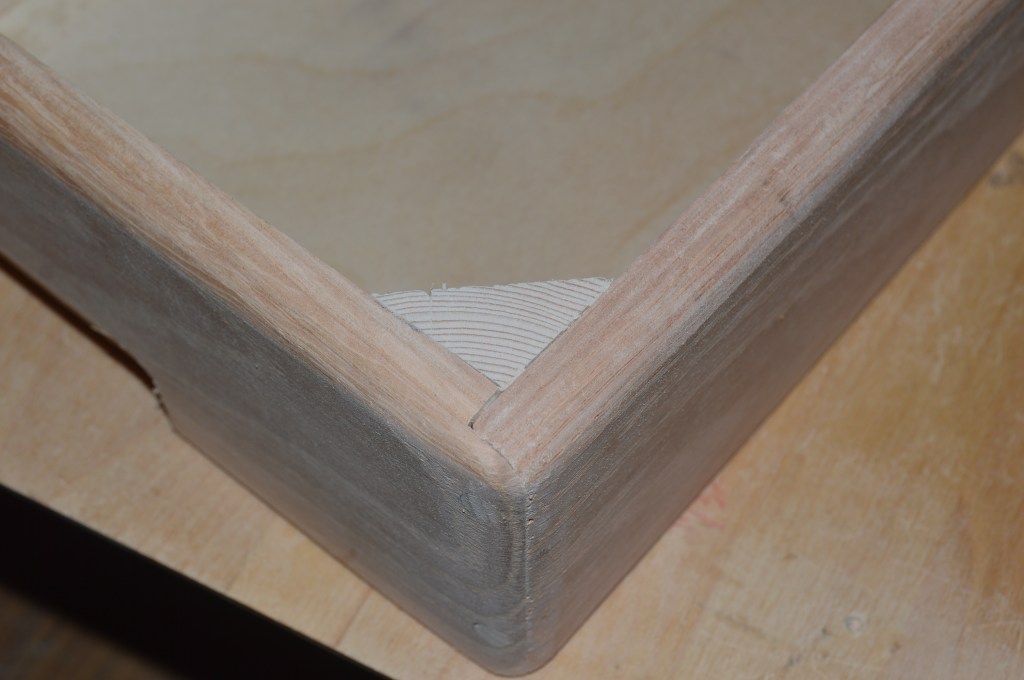

So, that’s it! The paint repairs turned out very nicely, and are hardly noticeable unless you know where to look. The machine turns smoothly and there is no perceptable slip or play in the assemblies. The parts are completely clean and the adjustments are just right for this machine. Finally, the pictures below show the final outcome. The customer ordered a custom made base in a Mocha stain, and this is base the machine is set into. All in all I think it is a very nice package, and I hope the customer is not only pleased, but uses her “new” Gimbels “Regular” machine for many years to come!

Well, I hope you like what you see and enjoyed the restoration process as much as I did… This unusual Gimbels model 1953 is and runs beautifully as well. Like I always say, some sewing machines need more, some need less, but they all get what they need, and now I can look forward to the next restoration!

Looking for a similarly restored quality vintage all metal sewing machine for your sewing room? Let us know! We specialize in custom orders and are happy to locate and restore the “perfect” machine for you!

As always, if you have any questions, or if I can be of any assistance, please contact me through Etsy or send me an email to Pungoliving@gmail.com.

Thanks for reading!

Lee